South Africa 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Staging Queer Temporalities 75 STAGING QUEER TEMPORALITIES

Staging Queer Temporalities 75 STAGING QUEER TEMPORALITIES A Look at Miss Gay Western Cape By: Olivia Bronson iss Gay Western Cape is a beauty pageant that takes place once a year in Cape Town. Though the event began during apartheid, it is only recently that it has gained visibil- ity and emerged as the largest gay pageant in South Africa. This project considers the Mways in which different queer communities in Cape Town strive to be seen in spaces that remain governed by the logics of racialized segregation. As evidenced with this event, queer communi- ties in Cape Town bare the wounds of the colonial and apartheid mechanism of informing and controlling groups on the basis of race. “Queer” as a politics, aesthetic, and movement takes many shapes within different contemporary contexts and serves as a necessary axis of conflict in relation to the imported, Westernized gay rights discourse. By representing an imagined world—a haven for oppressed, queer individuals to bear tiaras and six-inch heels to freely express their sexuali- ties through feminized gender identities—the pageant becomes a space in which queer practices supersede dominant gay rights discourse. It articulates an untold history through performance. I thus understand the pageant as both an archive and an act of resistance, in which participants enact a fragmented freedom and declare their existence in South Africa, the supposed rainbow nation. Berkeley Undergraduate Journal 76 FIGURE 1.1 Past winner of Miss Gay Western Cape I. Introduction to Topic This is what I say to my comrades in the struggle when they ask why I waste time fighting for ‘moffies,’ this is what I say to gay men and lesbians who ask me why I spend so much time struggling against apartheid when I should be fighting for gay rights. -

Economic Ascendance Is/As Moral Rightness: the New Religious Political Right in Post-Apartheid South Africa Part

Economic Ascendance is/as Moral Rightness: The New Religious Political Right in Post-apartheid South Africa Part One: The Political Introduction If one were to go by the paucity of academic scholarship on the broad New Right in the post-apartheid South African context, one would not be remiss for thinking that the country is immune from this global phenomenon. I say broad because there is some academic scholarship that deals only with the existence of right wing organisations at the end of the apartheid era (du Toit 1991, Grobbelaar et al. 1989, Schönteich 2004, Schönteich and Boshoff 2003, van Rooyen 1994, Visser 2007, Welsh 1988, 1989,1995, Zille 1988). In this older context, this work focuses on a number of white Right organisations, including their ideas of nationalism, the role of Christianity in their ideologies, as well as their opposition to reform in South Africa, especially the significance of the idea of partition in these organisations. Helen Zille’s list, for example, includes the Herstigte Nasionale Party, Conservative Party, Afrikaner People’s Guard, South African Bureau of Racial Affairs (SABRA), Society of Orange Workers, Forum for the Future, Stallard Foundation, Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), and the White Liberation Movement (BBB). There is also literature that deals with New Right ideology and its impact on South African education in the transition era by drawing on the broader literature on how the New Right was using education as a primary battleground globally (Fataar 1997, Kallaway 1989). Moreover, another narrow and newer literature exists that continues the focus on primarily extreme right organisations in South Africa that have found resonance in the global context of the rise of the so-called Alternative Right that rejects mainstream conservatism. -

Afrocentric Education: What Does It Mean to Toronto’S Black Parents?

Afrocentric Education: What does it mean to Toronto’s Black parents? by Patrick Radebe M.Ed., University of Toronto, 2005 B.A. (Hons.), University of Toronto, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Educational Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2017 Patrick Radebe, 2017 Abstract The miseducation of Black students attending Toronto metropolitan secondary schools, as evinced by poor grades and high dropout rates among the highest in Canada, begs the question of whether responsibility for this phenomenon lies with a public school system informed by a Eurocentric ethos. Drawing on Afrocentric Theory, this critical qualitative study examines Black parents’ perceptions of the Toronto Africentric Alternative School and Afrocentric education. Snowball sampling and ethnographic interviews, i.e., semi-structured interviews, were used to generate data. A total of 12 Black parents, three men and nine women, were interviewed over a 5-month period and data analyzed. It was found that while a majority of the respondents supported the Toronto Africentric Alternative School and Afrocentric education, some were ambivalent and others viewed the school and the education it provides as divisive and unnecessary. The research findings show that the majority of the participants were enamored with Afrocentricity, believing it to be a positive influence on Black lives. While they supported TAAS and AE, the minority, on the other hand, opposed the school and its educational model. The findings also revealed a Black community, divided between a majority seeking to preserve whatever remained of (their) African identity and a determined minority that viewed assimilation to be in the best interests of Black students. -

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

Africa Regional Workshop, Cape Town South Africa, 27 to 30 June 2016

Africa Regional Workshop, Cape Town South Africa, 27 to 30 June 2016 Report Outline 1. Introduction, and objectives of the workshop 2. Background and Approach to the workshop 3. Selection criteria and Preparation prior to the workshop 4. Attending the National Health Assembly 5. Programme/Agenda development 6. Workshop proceedings • 27 June‐Overview of research, historical context of ill health‐ campaigning and advocacy 28 June‐Capacity building and field visit • June‐ Knowledge generation and dissemination and policy dialogue • June‐ Movement building and plan of action 7. Outcomes of the workshop and follow up plans 8. Acknowledgements Introduction and Objectives of the workshop People’s Health Movement (PHM) held an Africa Regional workshop/International People’s Health University which took place from the 27th to 30 June 2016 at the University of Western Cape (UWC), Cape Town, South Africa. It was attended by approximately 35 PHM members from South Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Benin and Eritrea. The workshop was organised within the framework of the PHM / International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Research project on Civil Society Engagement for Health for All. Objectives for the workshop A four day regional workshop/IPHU took place in Cape Town South Africa at the University of Western Cape, School of Public Health. The objectives of the workshop included: • sharing the results of the action research on civil society engagement in the struggle for Health For All which took place in South Africa and DRC; • to learn more about the current forms/experiences of mobilisation for health in Africa; • to reflect together on challenges in movement building (e.g. -

Top Court Trims Executive Power Over Hawks

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Sunday 26 September 2021 Top court trims executive power over Hawks The Constitutional Court has not only agreed that legislation governing the Hawks does not provide adequate independence for the corruption-busting unit, it has 'deleted' the defective sections, notes Legalbrief. It found parts of the legislation that governs the specialist corruption-busting body unconstitutional, because they did not sufficiently insulate it from potential executive interference. This, notes a Business Day report, is the second time the court has found the legislation governing the Hawks, which replaced the Scorpions, unconstitutional for not being independent enough. The first time, the court sent it back to Parliament to fix. This time the court did the fixing, by cutting out the offending words and sections. The report says the idea behind the surgery on the South African Police Service (SAPS) Act was to ensure it had sufficient structural and operational independence, a constitutional requirement. In a majority judgment, Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng said: 'Our anti-corruption agency is not required to be absolutely independent. It, however, has to be adequately independent. 'And that must be evidenced by both its structural and operational autonomy.' The judgment resolved two cases initially brought separately - one by businessman Hugh Glenister, the other by the Helen Suzman Foundation (HSF), notes Business Day. Because both cases challenged the Hawks legislation on the grounds of independence, the two were joined. Glenister's case - that the Hawks could never be independent while located in the SAPS, which was rife with corruption - was rejected by the court. -

18. EPC Occasional Paper 5

EPC OCCASIONAL PAPER 5 OCCASIONAL PAPER EDUCATION AND THE FREEDOM CHARTER A Critical Appraisal What the Freedom Charter says The Doors of Learning and Culture Shall be Opened! The government shall discover, develop and encourage national talent for the enhancement of our cultural life; All the cultural treasures of mankind shall be open to all, by free exchange of books, ideas and contact with other lands; The aim of education shall be to teach the youth to love their people and their culture, to honour human brotherhood, liberty and peace; Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children; Higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit; Adult illiteracy shall be ended by a mass state education plan; Teachers shall have all the rights of other citizens; The colour bar in cultural life, in sport and in education shall be abolished. 1 EDUCATION AND THE FREEDOM CHARTER EPC OCCASIONAL PAPER 5 1 This paper first appeared as chapter 7 in the publication ‘60 YEARS OF THE FREEDOM CHARTER No cause to celebrate for the working class’ Published by Workers’ World Media Productions Tel: +27 (21) 4472727 Email: Lynn@wwmp. org.za Acknowledgements Research and Writing: Dale Mc Kinley (and previous publication, 50 Years of the Freedom Charter – A Cause to Celebrate? – Michael Blake). Project co-ordination, Editing and Proofreading: Martin Jansen Design and Layout: Nicolas Dieltiens Pictures and Graphics: Mayibuye Centre, Ilrig, Eric Miller, Oryx Media Cartoons contributed by Jonathan Shapiro (“Zapiro”) EPC OCCASIONAL PAPER 5 July 2015 Adapted by: Salim Vally (CERT) Design and layout: Mudney Halim (CERT) Cover design and EPC logo: Nomalizo Ngwenya Telephone: +27 11 482 3060 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION AND THE FREEDOM CHARTER Website: www.educatiopolicyconsortium.org.za EPC OCCASIONAL PAPER 5 2 Apartheid and education The overall impact was severe. -

No Valley Without Shadows MSF and the Fight for Affordable Arvs in South Africa

In the 1990s, even as the country celebrated its freedom from apartheid, South Africa descended into a chilling new crisis: an incurable disease was spreading so fast it soon became the fearsome stuff of myth and legend. The fight against HIV/AIDS in South Africa was a war fought on many fronts: against fear and ignorance so powerful it could lead to murder; against profiteering pharmaceutical companies whose patents safeguarded revenues at the cost of patients’ lives; and, most shockingly, against the South African government, which quickly emerged as the world leader in AIDS denialism. To take its place in this battle, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders would have to overcome internal resistance, seemingly impossible financial barriers, multiple lawsuits, and the shame and terror of the very people they were trying to help. How could a coalition of activists, doctors, and patients beat the odds to bring about startling innovations in treatment protocols, end the pharmaceutical companies’ legal challenges to low-cost drugs, and overturn an official policy of denial that originated in the nation’s highest political offices? This is the story. No Valley Without Shadows MSF and the Fight for Affordable ARVs in South Africa Written by Marta Darder, Liz McGregor, Carol Devine and other contributors. © 2014 Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders, Rue Dupré 94, 1090 Brussels No Valley Without Shadows is a publication by Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF). The texts in this publication are based on interviews with members of MSF and others who participated in the fight for affordable ARVs in South Africa. -

By Mr Justice Edwin Cameron Supreme Court of Appeal, Bloemfontein, South Africa

The Bentam Club Presidential Address Wednesday 24 March ‘When Judges Fail Justice’ by Mr Justice Edwin Cameron Supreme Court of Appeal, Bloemfontein, South Africa 1. It is a privilege and a pleasure for me to be with you this evening. The presidency of the Bentham Club is a particular honour. Its sole duty is to deliver tonight’s lecture. In fulfilling this office I hope you will not deal with me as Hazlitt, that astute and acerbic English Romantic essayist, dealt with Bentham.1 He denounced him for writing in a ‘barbarous philosophical jargon, with all the repetitions, parentheses, formalities, uncouth nomenclature and verbiage of law-Latin’. Hazlitt, who could, as they say, ‘get on a roll’, certainly did so in his critique of Bentham, whom he accused of writing ‘a language of his own that darkens knowledge’. His final rebuke to Bentham was the most piquant: ‘His works’, he said, ‘have been translated into French – they ought to be translated into English.’ I trust that we will not tonight need the services of a translator. 2. To introduce my theme I want to take you back nearly twenty years, to 3 September 1984. The place is in South Africa – a township 60 km south of Johannesburg. It is called Sharpeville. At the time its name already had ineradicable associations with black resistance to apartheid – and with the brutality of police responses to it. On 21 March 1960, 24 years before, the police gunned down more than sixty unarmed protestors – most of them shot in the back as they fled from the scene. -

The Judiciary As a Site of the Struggle for Political Power: a South African Perspective

The judiciary as a site of the struggle for political power: A South African perspective Freddy Mnyongani: [email protected] Department of Jurisprudence, University of South Africa (UNISA) 1. Introduction In any system of government, the judiciary occupies a vulnerable position. While it is itself vulnerable to domination by the ruling party, the judiciary must at all times try to be independent as it executes its task of protecting the weak and vulnerable of any society. History has however shown that in most African countries, the judiciary has on a number of occasions succumbed to the domination of the ruling power. The struggle to stay in power by the ruling elite is waged, among others, in the courts where laws are interpreted and applied by judges who see their role as the maintenance of the status quo. To date, a typical biography of a post-independence liberation leader turned president would make reference to a time spent in jail during the struggle for liberation.1 In the post-independence Sub-Saharan Africa, the situation regarding the role of the judiciary has not changed much. The imprisonment of opposition leaders, especially closer to elections continues to be a common occurrence. If not that, potential opponents are subjected to charges that are nothing but a display of power and might. An additional factor relates to the disputes surrounding election results, which inevitably end up in court. The role of the judiciary in mediating these disputes, which are highly political in nature, becomes crucial. As the tension heats up, the debate regarding the appointment of judges, their ideological background and their independence or lack thereof, become fodder for the media. -

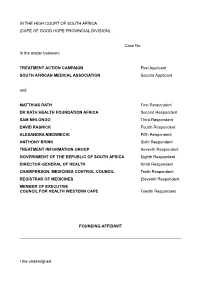

I, the Undersigned

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA (CAPE OF GOOD HOPE PROVINCIAL DIVISION) Case No. In the matter between: TREATMENT ACTION CAMPAIGN First Applicant SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Second Applicant and MATTHIAS RATH First Respondent DR RATH HEALTH FOUNDATION AFRICA Second Respondent SAM MHLONGO Third Respondent DAVID RASNICK Fourth Respondent ALEXANDRA NIEDWIECKI Fifth Respondent ANTHONY BRINK Sixth Respondent TREATMENT INFORMATION GROUP Seventh Respondent GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA Eighth Respondent DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF HEALTH Ninth Respondent CHAIRPERSON, MEDICINES CONTROL COUNCIL Tenth Respondent REGISTRAR OF MEDICINES Eleventh Respondent MEMBER OF EXECUTIVE COUNCIL FOR HEALTH WESTERN CAPE Twelfth Respondent FOUNDING AFFIDAVIT I the undersigned 2 NATHAN GEFFEN hereby affirm and state as follows: 1. I am an adult male. I am employed by the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) at 34 Main Road Muizenberg. 2. My position at the TAC is Co-ordinator of Policy, Research and Communications. I hold an M.Sc. in computer science from the University of Cape Town (UCT). 3. During 2000 and 2001 I was a lecturer in computer science at UCT. In this period I also volunteered for the TAC. This included serving as the organisation’s treasurer. From 2002 to the beginning of 2005 I was employed by the TAC as its national manager. 4. I am duly authorized by a resolution of the TAC National Executive Committee (NEC) to make this application and depose to this affidavit on its behalf. A copy of the resolution of the NEC on 4 October 2005 is attached (NG1). 5. The facts contained herein are true and correct and are within my personal knowledge unless the context indicates otherwise. -

Report Was Written by Scott Long, Consultant to Human Rights Watch and Former Program Director of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission

MORE THAN A NAME State-Sponsored Homophobia and Its Consequences in Southern Africa I wanted to speak to my president face to face one day and tell him, I am here. I wanted to say to him: I am not a word, I am not those things you call me. I wanted to say to him: I am more than a name. ⎯Francis Yabe Chisambisha, Zambian activist, interviewed in 2001. Human Rights Watch and The International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission Copyright © 2003 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-286-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2003102060 Cover photograph: Cover design by Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (44 20) 7713 1995, Fax: (44 20) 7713 1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (32 2) 732-2009, Fax: (32 2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to hrw-news-subscribe @igc.topica.com with “subscribe hrw-news” in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Addresses for IGLHRC 1375 Sutter Street, Suite 222, San Francisco, CA 94109 Tel: (415) 561-0633, Fax: (415) 561-0619, E-mail: [email protected] IGLHRC, c/o HRW 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 216-1814, Fax: (212) 216-1876, E-mail: [email protected] Roma 1 Mezzanine, (entrada por Versalles 63) Col.