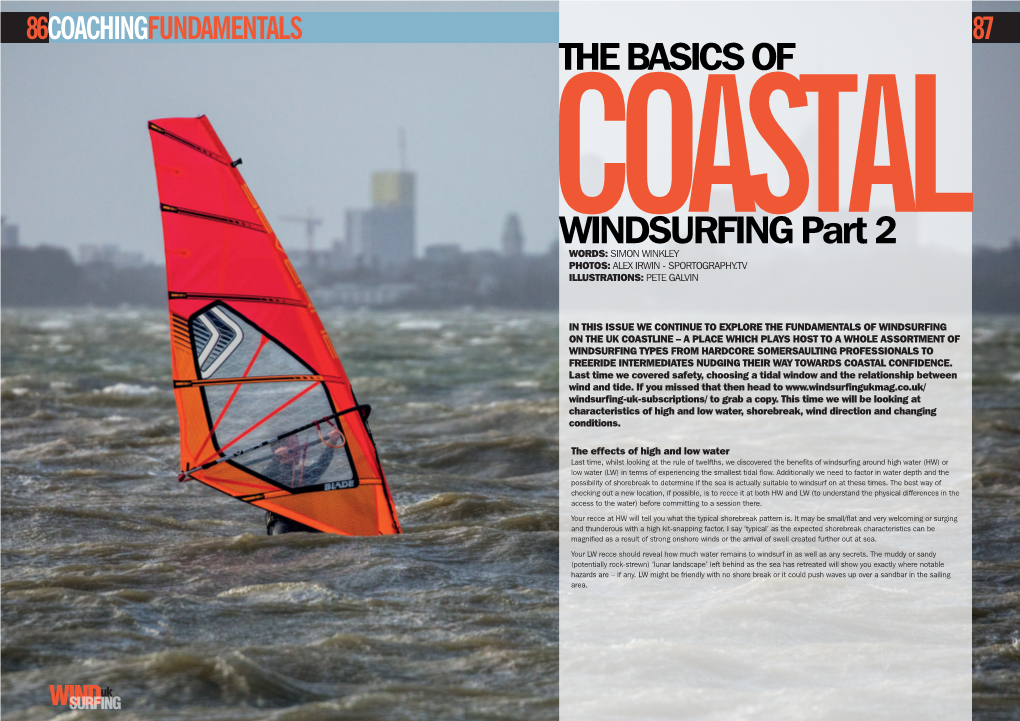

Windsurfing Uk Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix S6 Benthic Habitat Mapping of the Darwin Region

Technical Appendix S6 Ichthys Gas Field Development Project: benthic habitat mapping of the Darwin region—methods of data collection, collation and map production Ichthys Gas Field Development Project: Benthic Habitat Mapping of the Darwin Region— Methods of data collection, collation and map production Rev 0 | 30 March 2011 INPEX Document No. C036-AH-REP-0121 Phone: +61 408 857 056 E-mail: [email protected] Address: 8/260 West Coast Highway Scarborough, WA Web: www.geooceans.com Table of Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................................5 2. Data collection methods ........................................................6 2.1. Towed video survey ................................................................................... 6 2.1.1. Field sampling ............................................................................................ 6 2.1.2. Video transects .......................................................................................... 6 2.1.3. Towed video system .................................................................................. 6 2.1.4. Video data analysis and habitat classification............................................ 7 2.1.5. Quality assurance and quality control ........................................................ 9 2.1.6. Bathymetry ................................................................................................. 9 2.1.7. Depth correction for tide.......................................................................... -

Tide Simplified by Phil Clegg Sea Kayaking Anglesey

Tide Simplified By Phil Clegg Sea Kayaking Anglesey Tide is one of those areas that the more you learn about it, the more you realise you don’t know. As sea kayakers, and not necessarily scientists, we don’t have to know every detail but a simplified understanding can help us to understand and predict what we might expect to see when we are out on the water. In this article we look at the areas of tide you need to know about without having to look it up in a book. Causes of tides To understand tide is convenient to imagine the earth with an envelope of water all around it, spinning once every 24 hours on its north-south axis with the moon on a line parallel to the equator. Moon Gravity A B Earth Ocean C The tides are primarily caused by the gravitational attraction of the moon. Simplifying a bit, at point A the gravitational pull is the strongest causing a high tide, point B experiences a medium pull towards the moon, while point C has the weakest pull causing a second high tide. Because the earth spins once every 24 hours, at any location on its surface there are two high tides and two low tides a day. There are approximately six hours between high tide and low tide. One way of predicting the approximate time of high tide is to add 50 minutes to the high tide of the previous day. The sun has a similar but weaker gravitational effect on the tides. On average this is about 40 percent of that of the moon. -

Maine Guide Training

Maine Guide Training 2021 History of Maine Guides ● First hired guides in Maine were Abenaki people who led European explorers, military officials, traders, priests and lumbermen. ● Guiding industry emerged in late 1900s as people in more urban and industrialized regions sought wilderness for recreation ● Cornelia “Fly Rod” Crosby was first guide licensed in 1897; 1700 others were licensed that year. Maine’s Legal Definition of “Guide” Any person who receives any form of remuneration for his services in accompanying or assisting any person in the fields, forests or on the waters or ice within the jurisdiction of the State while hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, snowmobiling or camping at a primitive camping area. Sea Kayaking Guide Specialization Guides can lead paddlesports trips on the State's territorial seas and tributaries of the State up to the head of tide and out to the three mile limit. This classification includes overnight camping trips in conjunction with those sea-kayaking and paddlesports. Testing Process 1. Criminal Background Check 2. Oral Examination ■ Chart and compass work ■ Catastrophic scenario 3. Written Examination (minimum score of 70 to pass) What Maine Sea Kayak Guides CAn Do ● Lead commercial sea kayaking and SUP trips on Maine’s coastal waters ● Lead overnight camping trips associated with these trips (new as of 2005) ● Lead trips with up to 12 people per guide What Sea Kayak Guides CAN’T Do ● Lead paddling trips on inland waters (by kayak, canoe, SUP or raft) ● Take clients fishing or hunting ● Lead trips that require another type of guide license What are the qualities that you most appreciated in guides you’ve encountered? ● Wilderness Guide Association’s Definition of a Guide A trained and experienced professional with a high level of nature awareness. -

Oceans 11 Teaching Resources Vol 1

Oceans 11 A Teaching Resource Volume 1 1 Foreword Oceans 11 curriculum was developed by the Nova Scotia Department of Education as part of a joint project with the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans. This curriculum reflects the framework described in Foundation for the Atlantic Canada Science Curriculum. Oceans 11 satisfies the second science credit requirement for high school graduation. Oceans 11 includes the following modules: Structure and Motion, Marine Biome, Coastal Zone, Aquaculture, and Fisheries. Oceans 11: A Teaching Resource, Volume 1 is intended to complement the curriculum guide, Oceans 11. The sample activities in this resource address the outcomes described in Oceans 11 for the three compulsory modules: Structure and Motion, Marine Biome, and Coastal Zone. Oceans 11: A Teaching Resource, Volume 2 is intended to complement Oceans 11. The sample activities in it address the outcomes for the modules Aquaculture and Fisheries. Teachers may choose to do one of these units or to divide their class into groups that focus on a unit. 2 Contents Structure and Motion Introduction Materials The Ocean Industry in Nova Scotia The Ocean Industry in Nova Scotia, Teacher Notes When Humans and the Ocean Meet When Humans and the Ocean Meet, Teacher Notes Bodies of Water Bodies of Water, Teacher Notes Bathymetric Profile Sketching Bathymetric Profile Sketching, Teacher Notes Water Facts Water Facts, Teacher Notes Comparing Densities of Fresh Water and Seawater Comparing Densities of Fresh Water and Seawater, Teacher Notes The Effects -

Enon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project Final Report Site Specific

Enon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project Final Report Site Specific Archaeological Restoration at SEW-440 and SEW-488 Restoration Project 95007B Final Report Linda Finn Yarborough United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Chugach National Forest 3301 C St., Suite 300 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 October 1997 Site Specific Archaeological Restoration at SEW440 and SEW488 Restoration Project 95007B Final Report Siw:The project effort was initiated under Restoration Project 94007B.An annual progress report was issued in January, 1995 by Yarborough, L., under the title Restoration ~ -1995. Theproject continued under Restoration Project 95007B, the subject of annual this report. A second progress report was prepared in September 1995 by Yarborough, L., under the title 1s Reuort. Seutember 1995. FY 95 wasthe last field season for this project. Data analysis and project report preparation took place in FY 96 and FY97.Papers were prepared for presentation and peer reviewed publication, and results were presented to the public in FY 97. Abstract: Project 94007 provided for restoration of two archaeological sites damaged during the Exxon Vuldez Oil Spill and its subsequent cleanup program. Test excavations were carried out at both SEW-440 and SEW-488 during 1994. Analysis and completion of excavations at SEW-488 took place in 1995. Analysis continued in 1996 and 1997. Each site was assessed in the field and mapped prior to testing. Data recovery work yielded both environmental and cultural information. Both sites appear to have been intermittently occupied, SEW-440 over a period of almost 2000 years, and SEW-488 for up to 3000 years. Artifact and zooarchaeological analyses resulted in information on prehistoric technology, subsistence, seasonality and site use. -

Tidal Theory

TIDAL THEORY By Phil Clegg, Sea Kayaking Anglesey Tide is one of those areas that the more you learn about it, the more you realise you don’t know. As sea kayakers (and dinghy sailors) and not necessarily scientists, we don’t have to know every detail but a simplified understanding can help us to understand and predict what we might expect to see when we are out on the water. Causes of Tide To understand tide it is convenient to imagine the earth with an envelope of water all around it, spinning once every 24 hours on its north-south axis with the moon on a line parallel to the equator. Moon Gravity A B Earth C Ocean The tides are primarily caused by the gravitational attraction of the moon. Simplifying a bit, at point A the gravitational pull is the strongest causing a high tide, point B experiences a medium pull towards the moon, while point C has the weakest pull causing a second high tide. Because the earth spins once every 24 hours, at any location on its surface there are two high tides and two low tides a day. There are approximately six hours between high tide and low tide. One way of predicting the approximate time of high tide is to add 50 minutes to the high tide of the previous day. The sun has a similar but weaker gravitational effect on the tides. On average this is about 40 percent of that of the moon. The main importance of the sun is the effect of either reinforcing the moon’s force or reducing it depending on their positions relative to each other. -

Tide 1 Tides Are the Rise and Fall of Sea Levels Caused by the Combined

Tide 1 Tide The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, The Bay of Fundy at Hall's Harbour, Nova Scotia during high tide Nova Scotia during low tide Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon and the Sun and the rotation of the Earth. Most places in the ocean usually experience two high tides and two low tides each day (semidiurnal tide), but some locations experience only one high and one low tide each day (diurnal tide). The times and amplitude of the tides at the coast are influenced by the alignment of the Sun and Moon, by the pattern of tides in the deep ocean (see figure 4) and by the shape of the coastline and near-shore bathymetry.[1] [2] [3] Most coastal areas experience two high and two low tides per day. The gravitational effect of the Moon on the surface of the Earth is the same when it is directly overhead as when it is directly underfoot. The Moon orbits the Earth in the same direction the Earth rotates on its axis, so it takes slightly more than a day—about 24 hours and 50 minutes—for the Moon to return to the same location in the sky. During this time, it has passed overhead once and underfoot once, so in many places the period of strongest tidal forcing is 12 hours and 25 minutes. The high tides do not necessarily occur when the Moon is overhead or underfoot, but the period of the forcing still determines the time between high tides. -

Sailing Manual

wildwildabout WHAT IS MY CONNECTION TO WATER? WILD About Sports: What is My Connection to Water x CWFWildABoutSports.org © 2014 Canadian Wildlife Federation 1 INTRODUCTION his resource manual is designed as SECTION TWO: HOW DO HABITATS WORK? supplementary material for instructors who T Activities in this section provide a foundation are teaching children about best practices in for the understanding that people and wildlife water sports as well as broader concepts of have similar needs. conservation, particularly as they pertain to the health of the Earth’s water supply. SECTION THREE: ORGANIZATION OF THE MATERIALS WHAT’S MY CONNECTION TO WATER? These materials were selected and designed Activities in this section help students for instructors of children ages five and up. recognize and evaluate their direct and They are split into five sections of instruction. indirect connections to the environment. Each section has three to four activities to choose from, with the exception of section SECTION FOUR: five, where we suggest a celebration of POSITIVE HUMAN ACTION the good work done over the previous four sections. Activities in this section help students recognize, evaluate and make responsible Instructors are free to pick and choose any choices in their own lives, reflecting the part of an activity to suit their existing plans. knowledge and skills they may have acquired The materials are organized in a thematic in earlier activities. and developmental order, which can help students to acquire knowledge and skills as they learn about natural resources, SECTION FIVE: particularly in aquatic environments. GRADUATION CELEBRATION! It’s time to celebrate a week of learning! SECTION ONE: Students will be encouraged to present AWARENESS AND APPRECIATION their new knowledge and attitudes with the community through visual art, writing and Activities in this section will naturally dramatic presentations. -

Sea Kayak Navigation Franco Ferrero

SEA KAYAK NAVIGATION Franco Ferrero A PRACTICAL MANUAL 2nd edition ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE FOR FINDING YOUR WAY AT SEA SEA KAYAK NAVIGATION Franco Ferrero A PRACTICAL MANUAL First published 1999 Second edition 2007 Published in Great Britain 2007 by Pesda Press Unit 22, Galeri Doc Victoria Caernarfon Gwynedd LL55 1SQ Reprinted with minor corrections 2009 © Copyright 2007 Franco Ferrero ISBN: 978−1−906095−03−1 The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Printed and bound in Poland. www.polskabook.pl THE AUTHOR Franco Ferrero Franco began sea kayaking at the age of fifteen, and was lucky enough to be brought up in the Channel Islands. The small scattered islands, fast tidal streams and summer fogs ensured that navigation was a key skill learnt at an early age. In 1978 he was one of a team of three Jerseymen who completed the first circumnavigation of Ireland by sea kayak. In 1989, with Kevin Danforth, he made a record breaking unsupported crossing of the North Sea. Since then he has paddled in many parts of the world including Nepal, Scandinavia, the coast of Brittany in France, the European Alps, Peru and Western Canada. He is the managing director of Pesda Press and still occasionally manages to fit in some freelance coaching (as a BCU Level 5 Coach). -

Maralyn Miller Volume No. 36 No. 11 December 2016

Volume No. 36 No. 11 December 2016 Editor: Maralyn Miller 1 CRUISING DIVISION OFFICE BEARERS – 2016 - 2017 Cruising Captain Michael Mulholland-Licht 0418-476-216 Vice-Commodore Michael Mulholland-Licht 0418-476-216 Cruising Secretary Evan Hodge 0419-247-500 Treasurer Evan Hodge 0419-247-500 Membership Kelly Nunn-Clark 0457-007-554 Name Tags Lena D’Alton / Jean Parker Compass Rose Committee Members Coordinator Safety Coordinator Phil Darling 0411-882-760 Waterways User Group Mike McEvoy 9968-1777 Sailing Committee Michael Mulholland-Licht 0418-476-216 Guest Speakers Committee Members as required On Water Events Evan Hodge, Michael Mulholland-Licht, Michael 0418-476-216 Coordinator Phil Darling, Kelly Nunn-Clark Phil 0419-247-500 On Land Events Kelly Clark, Gill Attersall Coordinators Committee Members Michael Mulholland-Licht, Phil Darling, Dorothy Theeboom, Kelly Nunn-Clark, Evan Hodge Editor's note: Deadline for the next edition of the Compass Rose, is 2nd February 2017 The EDITOR for the next Compass Rose is Trevor D’Alton Please forward contributions via email to the editor: [email protected] Opinions expressed in the Compass Rose are those of the contributors, and do not necessarily reflect opinions of either Middle Harbour Yacht Club or the Cruising Division 2 MHYC Cruising Division Program 2016/17 December 9th Christmas Party (replaces December meeting) January th 2017 14 January Cup & 2 Handed Race – MHYC Feature Event 16th Post New Year BBQ and get together. 26th Australia Day 28th Chaos and Bedlam Point Cup – MHYC Feature Event February 18th Barefoot Ball 20th Cruising Division Meeting 24th & 25th Gosford Challenge TBA Late Summer Cruise March 4th & 5th Sydney Harbour Regatta 11th & 12th Harbour Night Sail and raft-up. -

Weather for Offshore Sailing Outline

Weather for Offshore Sailing Outline • Review of weather basics – Cloud types – Wind and waves – Fronts and air masses • Weather for day sailing – Sources of weather information – Tides and currents – Practical considerations • Weather for passage planning – Sources of weather information – Route planning – Practical considerations • Weather underway – Sources of weather information – Practical considerations Outline • Review of weather basics – Cloud types – Wind and waves – Fronts and air masses • Weather for day sailing – Sources of weather information – Tides and currents – Practical considerations • Weather for passage planning – Sources of weather information – Route planning – Practical considerations • Weather underway – Sources of weather information – Practical considerations Outline • Review of weather basics – Cloud types – Fronts and air masses – Wind and waves • Weather for day sailing – Sources of weather information – Tides and currents – Practical considerations • Weather for passage planning – Sources of weather information – Route planning – Practical considerations • Weather underway – Sources of weather information – Practical considerations Sea Breeze Front Sea Breeze Front Land Breeze Front Outline • Review of weather basics – Cloud types – Fronts and air masses – Wind and waves • Weather for day sailing – Sources of weather information – Tides and currents – Practical considerations • Weather for passage planning – Sources of weather information – Route planning – Practical considerations • Weather underway – Sources -

Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications Wildlife Biology 2007 Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring Michelle L. Kissling Mason Reid Paul M. Lukacs University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Scott M. Gende Stephen B. Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/wildbio_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kissling, Michelle L.; Reid, Mason; Lukacs, Paul M.; Gende, Scott M.; and Lewis, Stephen B., "Understanding Abundance Patterns of a Declining Seabird: Implications for Monitoring" (2007). Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications. 68. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/wildbio_pubs/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Biology at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ecological Applications , 17(8), 2007, pp. 2164–2174 Ó 2007 by the Ecological Society of America UNDERSTANDING ABUNDANCE PATTERNS OF A DECLINING SEABIRD: IMPLICATIONS FOR MONITORING 1,6 2 3 4 5 MICHELLE L. K ISSLING , MASON REID , PAUL M. L UKACS , SCOTT M. G ENDE , AND STEPHEN B. L EWIS 1U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 3000 Vintage Boulevard, Suite 201, Juneau, Alaska 99801 USA 2National Park Service, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, P.O. Box 439, Copper Center, Alaska 99573 USA 3Colorado Division of Wildlife, 317 W. Prospect Road, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 USA 4National Park Service, Glacier Bay Field Station, 3100 National Park Road, Juneau, Alaska 99801 USA 5Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, P.O.