Children's Literature in Italy, 1929-1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating Italy's Past Through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and Tv

INVESTIGATING ITALY’S PAST THROUGH HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION, FILMS, AND TV SERIES Murder in the Age of Chaos B P ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA Aims of the Series This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Barbara Pezzotti Investigating Italy’s Past through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and TV Series Murder in the Age of Chaos Barbara Pezzotti Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-60310-4 ISBN 978-1-349-94908-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-94908-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948747 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

Youth, Gender, and Education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 Jennifer L

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2015 The model of masculinity: Youth, gender, and education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 Jennifer L. Nehrt James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nehrt, Jennifer L., "The model of masculinity: Youth, gender, and education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939" (2015). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 66. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Model of Masculinity: Youth, Gender, and Education in Fascist Italy, 1922-1939 _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Jennifer Lynn Nehrt May 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of History, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Jessica Davis, Ph.D. Philip Frana, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History Interim Director, Honors Program Reader: Emily Westkaemper, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, History Reader: Christian Davis, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, History PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Honors Symposium on April 24, 2015. -

Robert O. Paxton-The Anatomy of Fascism -Knopf

Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page b also by robert o. paxton French Peasant Fascism Europe in the Twentieth Century Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 Parades and Politics at Vichy Vichy France and the Jews (with Michael R. Marrus) Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page i THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page ii Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iii THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM ROBERT O. PAXTON Alfred A. Knopf New York 2004 Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iv this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf Copyright © 2004 by Robert O. Paxton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. isbn: 1-4000-4094-9 lc: 2004100489 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page v To Sarah Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vi Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vii contents Preface xi chapter 1 Introduction 3 The Invention of Fascism 3 Images of Fascism 9 Strategies 15 Where Do We Go from Here? 20 chapter 2 Creating Fascist Movements 24 The Immediate Background 28 Intellectual, Cultural, and Emotional -

“Justice League Detroit”!

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! t 201 2 A ugus o.58 N . 9 5 $ 8 . d e v r e s e R s t h ® g i R l l A . s c i m o C C IN THE BRONZE AGE! D © & THE SATELLITE YEARS M T a c i r e INJUSTICE GANG m A f o e MARVEL’s JLA, u g a e L SQUADRON SUPREME e c i t s u J UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CROSSOVERS 7 A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN 0 8 2 “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY 6 7 7 CONWAY & DAN JURGENS 2 8 5 6 And the team fans 2 8 love to hate — 1 “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “BaTman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray . s c i m COVER COLORIST o C BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury .........................................................2 Glenn “Green LanTern” WhiTmore C D © PROOFREADER & Whoever was sTuck on MoniTor DuTy FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 M T . A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators a c i r SPECIAL THANKS e m Jerry Boyd A Rob Kelly f o Michael Browning EllioT S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers ................29 e u Rich Buckler g Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… a e L Russ Burlingame Brad MelTzer e c i T Snapper Carr Mi ke’s Amazing s u J Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme ....................................33 e h T ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders g n i r Gerry Conway Eri c Nolen- r a T s DC Comics WeaThingTon , ) 6 J. -

Consensus for Mussolini? Popular Opinion in the Province of Venice (1922-1943)

UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM SCHOOL OF HISTORY AND CULTURES Department of History PhD in Modern History Consensus for Mussolini? Popular opinion in the Province of Venice (1922-1943) Supervisor: Prof. Sabine Lee Student: Marco Tiozzo Fasiolo ACADEMIC YEAR 2016-2017 2 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the University of Birmingham is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of my words. 3 Abstract The thesis focuses on the response of Venice province population to the rise of Fascism and to the regime’s attempts to fascistise Italian society. -

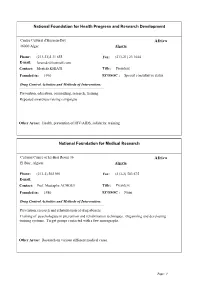

NGO Directory

National Foundation for Health Progress and Research Development Centre Culturel d'Hussein-Day Africa 16000 Alger Algeria Phone: (213-21)2 31 655 Fax: (213-21) 23 1644 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Mostefa KHIATI Title: President Founded in: 1990 ECOSOC : Special consultative status Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, counselling, research, training Repeated awareness raising campaigns Other Areas: Health, prevention of HIV/AIDS, solidarity, training National Foundation for Medical Research Cultural Centre of El-Biar Room 36 Africa El Biar, Algiers Algeria Phone: (213-2) 502 991 Fax: (213-2) 503 675 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Mustapha ACHOUI Title: President Founded in: 1980 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, research and rehabilitation of drug abusers. Training of psychologists in prevention and rehabilitation techniques. Organizing and developing training systems. Target groups contacted with a few monographs. Other Areas: Research on various different medical cases. Page: 1 Movimento Nacional Vida Livre M.N.V.L. Av. Comandante Valodia No. 283, 2. And.P.24. Africa C.P. 3969 Angola, Rep. Of Luanda Phone: (244-2) 443 887 Fax: E-mail: Contact: Dr. Celestino Samuel Miezi Title: National Director, Professor Founded in: 1989 ECOSOC : Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, treatment, counselling, rehabilitation, training, and criminology To combat drugs and its consequences through specialized psychotherapy and detoxification Other Areas: Health, psychotherapy, ergo therapy Maison Blanche (CERMA) 03 BP 1718 Africa Cotonou Benin Phone: (229) 300850/302816 Fax: (229) 30 04 26 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Rene Gilbert AHYI Title: President Founded in: 1988 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, treatment, training and education. -

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

Metallurgy, Society and the Bronze/Iron Transition in the East Mediterranean and the Near East

~I ' ! SYDNEY PICKLES and EDGAR PELTENBURG METALLURGY, SOCIETY AND THE BRONZE/IRON TRANSITION IN THE EAST MEDITERRANEAN AND THE NEAR EAST Reprinted from the Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus 1998 NICOSIA 1998 METALLURGY, SOCIETY AND THE BRONZE/IRON TRANSITION IN THE EAST MEDITERRANEAN AND THE NEAR EAST Sydney Pickles and Edgar Peltenburg INTRODUCTION Stage 2. Iron began to be used for utilitarian objects but bronze still predominated. In so fa r as it refers to the chronological sequ ence of dominant technologies in the Old World, Stage 3. Iron was in general use for utilitarian the three ages concept of archaeological classifi objects. cation cannot -be challenged. Difficul ties arise Towards the end of the 13th century B.C. the when attempts are made to specify precise bound archaeological record of the Near East shows in aries between the epochs, both chronologically creasing use of iron for cutting tools and other and technologically, and to associate distinctive working implements (McGovern 1987, Stech cultural patterns wi th the technological phases. Wheeler et al. 1981, McNutt 1990), gradually re Some increase in cultural complexity was neces placing bronze and even wood and stone for uses sary for metallurgical innovation to be possible, for which metal had hitherto been too costly a lu but the material cultures and social orders were xury, e.g. its use for ploughshares made possible themselves drastically changed by the availability the culti vati on of ground previously considered and use of metals, initially by an elite but later, in too hard. In the Eastern Mediterranean this pro the Iron Age, by even the humblest ploughman in cess occupied most of the 12th, 11 th and 10th the fields. -

Jury Convicts Man in Killing

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Olympics: USA men’s boxing has revival in Tokyo /B1 THURSDAY T O D A Y C I T R U S C O U N T Y & n e x t m o r n i n g HIGH 84 Numerous LOW storms. Localized flooding possible. 73 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com AUGUST 5, 2021 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community $1 VOL. 126 ISSUE 302 SO YOU KNOW I The Florida Depart- ment of Health Jury convicts man in killing has ceased the daily COVID-19 re- ports that have been used to track Michael Ball, 64, faces possibility of life in prison for shooting of neighbor changes in the MIKE WRIGHT It’s as simple as prison. Sentenc- video recording of an in- video. “I hate it but he number of corona- Staff writer that,” Ball said. ing was set for terview detectives con- didn’t give me no virus cases and A four-man, Sept. 15. ducted with Ball at the choice.” deaths in the state. A Beverly Hills man on two-woman jury Ball, 64, was county jail after the Ball said he had just trial for second-degree held Ball respon- charged in the shooting. finished cleaning the murder in the shooting sible, convicting March 25, 2020, During the interview, handgun when he stuffed NEWS death of a neighbor said him as charged death of 32-year- Ball repeatedly states he it in his waistband, cov- he was afraid for his life Wednesday eve- old Tyler Dorbert shot Dorbert out of fear ered with a sweatshirt, BRIEFS when he pulled the ning at the conclu- Michael on a street outside based on an assault that and went outside to get trigger. -

Caritas Un Incontro Una Storia

Un incontro, una storia è un progetto promosso dalla Caritas Diocesana di Roma Palazzo del Vicariato Piazza S. Giovanni in Laterano, 6/a – 00184 Roma T. 06 69886424 E-mail: [email protected] www.caritasroma.it Direttore Caritas di Roma: don Benoni Ambarus Ideazione e progettazione: Marina Piccone Organizzazione: Area Pace e Mondialità Cittadella della Carità Santa Giacinta Via Casilina Vecchia, 19 – 00182 Roma Commissione di valutazione del concorso: p. Camillo Ripamonti, Anab Farah Abdi, Sandro Baldi, Paola Barretta, Gianni Del Bufalo, Isabella Di Chio, Ahmad Ejaz, Elena Maietich, Lazzaro Pappagallo, Vinicio Ongini, Andrea Segre I premi per i vincitori sono stati messi a disposizione da: Associazione Stampa Romana Libera Accademia di Roma & Università Popolare dello Sport Teatro Le Sedie Il libro contiene le migliori opere selezionate dalla commissione di valutazione Si ringrazia per la collaborazione: il Miur (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca) il Comune di Roma Il concorso è stato realizzato nell’anno 2019/2020 Progetto grafico e illustrazione di copertina: Andrea Morucci Un incontro, una storia Sommario Introduzione . 11 Opere individuali Fascia d’età 11/14 La mia prima parola italiana . (Opera vincitrice) . 16 Intervista al mio amico Tanjim Rafid Kazi Enayat Ullah La mia storia . 19 Matilde Vallati Angel . 23 Valerio Castellotti La mia compagna di classe . 27 Giada Frappini Essere a casa Intervista al mio amico Rafid . 30 Tanjim Thasin Fascia d’età 15/19 Angie (Opera vincitrice) . 34 Camilla Barberi Una storia “normale” . 39 Eleonora Salata Un ragazzo preciso . 42 Abaid Malik Sulla loro pelle . 48 Nicolò Saputi Guardo la luna . 52 Erion Brace Admon Alhabibi .