Suing Organized Piracy: an Application of Maritime Torts To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swedish Sea Captains Contents 77Th Year of Operations

Swedish sea captains Contents 77th year of operations Sweden’s first official training: a mate’s certifi cate was key figures __________________________ 2 educational institution for seamen, required for admission to the sea the Mates’ School in Stockholm, was captain’s class, a pass as second engineer presentation ________________________ 3 established on 4 June 1658, following was needed for a fi rst engineer’s class a royal letter of command. For many and so on. The tuition lasted for seven years it was the only one, but later it to nine months. However, skippers and comments by the chairman was joined by the ‘lower navigational third engineers made do with three. and the managing director ___ 4 institutions’ in Visby and Karlshamn. The navigation schools became naval The next royal letter on the subject command schools, were converted to market review _____________________ 4 did not come until 7 April 1841, when university college level education in 1980 special navigation schools were set up and were whittled down to two loca- summary of income statements in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Gävle, tions, Kalmar and Gothenburg. Today and balance sheets _______________ 6 Malmö and Kalmar. Härnösand, Visby, an aspiring sea captain combines the Karlshamn, Västervik and Strömstad usual technology and seamanship with were added later. leadership. The tuition extends over administration report ___________7 In 1911 the Swedish Parliament four years of study, three in classrooms, reduced the number of schools to the on simulators and on exercise ships, income statement ________________ 8 original fi ve. Engineer training was and one practical year on commercial introduced into the navigation schools vessels. -

Look at All of the Sea Captains That Lived on Pleasant Street! Hyannis

Hyannis N Transportation Center 1 On July 8, 1854, The You are here! Cape Cod Railroad Company reached the town of Hyannis. It reached Provincetown in July 1873, and was known, by then, as the Old Colony Railroad. This postcard shows the original S railroad depot in Hyannis. 1 MAIN STREET 2 MAIN STREET SCHOOL STREET 3 The Cash Block 3 building was built by Captain 5 Built before 1770, Alexander Baxter, often known as by Captain Allen Hallet, this is the “ the Father of Hyannis”, for his 4 second oldest residence existing in Hyannis, commitment to developing the village still on it’s original foundation and location. in the early 19th century. 5 2 In 1874, PLEASANT STREET President Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Hyannis on the River Queen as part 6 School Street Along of the inauguration of the railroad this picturesque street you will see extension to Provincetown. With several Greek Revival Cottages origi- much fanfare, he spoke to crowds nally built from 1825-1924. If you have at this corner and at each stop on 8 a little extra time, saunter here. his way to Provincetown on the Old 7 Colony Railroad! OLD COLO NY ROAD NY COLO OLD 10 9 11 12 13 6 Built in 1852, 14 Captain Allen Crowell Homestead, 20 in 1666, this area of remains a fine original example of the Greek Revival land was granted to the first settler style of architecture. Captain Crowell (1821-1891) SOUTH STREET of Hyannis, Nicholas Davis, by the was well known for sailing all of the Seven Seas! 15 leader of the Mattakeese Indians, Yanno, Visit the Barn/Stable to see the PLEASANT STREET also called Iyannough. -

A Timeline of Alexandria's Waterfront

City of Alexandria Office of Historic Alexandria Alexandria Archaeology Studies of the Old Waterfront A Timeline of Alexandria’s Waterfront By Diane Riker July 2008 In the life story of a city, geography is destiny. And so, it is no surprise that Alexandria was destined to become, at least for a time, a major seaport. Here, close to the Potomac’s headwaters, the river’s natural channel touched shore at two points. Between the two lay a crescent of bluffs, backed by abundant woods and fertile fields. Millennia before the town existed, grasslands bordered a much narrower Potomac, providing hunting and fishing grounds for the earliest Americans. Our timeline begins with a remarkable find in the summer of 2007. Prehistoric Alexandria Alexandria Archaeology Museum 11,000 B.C. In 2007 a broken spear point dating back an estimated 13,000 years is uncovered by archaeologists at a Civil War cemetery above Hunting Creek. The Clovis Point is Alexandria’s oldest artifact. Similar tools, also made of quartzite, have been found in Europe and antedate the Paleolithic period. Perhaps the first Europeans here were not who we thought they were. 9,000 B.C. Following the melting of the glaciers, sea levels rise and the Potomac River becomes much wider. Ancient spear points have been found at Jones Point where native Americans probably hunted deer and other mammals. 1,000 B.C. Charred hearthstones and bowl fragments indicate a more settled population. The river runs with shad and sturgeon. The tidelands provide rich soil for cultivation. At Jones Point in 1990 indications of a “village” are found. -

Booklet 1.Pdf

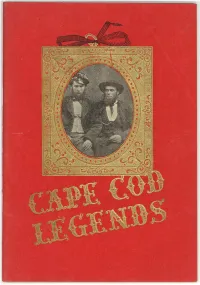

Captain Horatio S. Kelly, master of the famous ship "Eagle Wing." The yOtt11g man with him is an unknown passCllger. Captain Kelly was only twe11ty years old at tlJis time and already master of his own ship. Cape Cod Legends Copyright 1935 CAPE COD ADVANCEMENT PLAN, HYANNIS, MASS. Harry V. Lawrence, Falmouth, C/lairman ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Foreword ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ARNS OF CLIPPER SHIPS AND deep-sea CAPTains, TALES OF QUAINT ANCESTORS WHOSE Y PICTURES HANG IN Cape Cod's BEAUTIFUL homes, STORIES OF CHERISHED HEIRLOOMS, AND FANCIFUL LEGENDS OF THIS Lore-fILLEDLAND -HOW MANy SUMMER VISItors, LONG ENCHANTED By CaPE CoD'S UNIQUE charm, HAVE LONGED TO HEAR Them? Well, HERE THEy ARE I THE OLD SEA CAPTAINS ARE A VANISHING race; ONLy PHANTOM ships, WITHGHOSTLy SAILS, ARE SEEN OFFSHORE TODay. GrAVE eyeD PilGRIMS HAVE LONG BEEN AT REST UNDER TUMBLING HEADSTONES IN ANCIENT CAPE GRaveyarDs. But THE ROMANTIC Days OF THE LONg-AGO CaPE, AND THEPICTURESQUE ways OF ITS LONg-agO people, STILL LIve, HANDED DOWN THROUGHTALE AND LEGENDFROM GENERATIONTO GENERATION. In A SEARCH LAST year FOR SOME OF THE TREASURES OF THIS PAST, THE Cape COD ChamBER OF Commerce OFFERED A NUMBER OF CASH PRIzes FOR THE BEST HISTORICAL DATa, LEGENDS, STORIes, ANECDOTEs, AND PHOTOGRAPHS CONCERNING Cape COD. Preference WAS GIVENTO UNPUBLISHED MATERIAL AND MOST OF THE STORIES AND PHOTOGRAPHS IN THIS BOOKLETHAVE ne\-ER BEFORE BEEN PRINted. From DUSTy ATTIcs, FROM GREAT-graNDFATHER's SEA CHEST, FROM OLD, OLD DESKS AND TRUNks, FROMPLUSH COVERED ALBUMS, THE yeLLOWED DOCUMENTs, diaries, OLD LETTERS AND DAGUEr- REOTyPES POUREDIN. SO FASCINATING AND SO REMARKABLy TRUE OF THE EARLy CaPE AND ITS PEOPLE WAS THIS WEALTH OF MATERIALTHAT IT WAS DECIDED TO COMPILE A SMALL PART OF ITIN PERMANENT FORM AND PRESENT IT TO THOSE WHO DO LOVE OR WOULD LOVE THIS BEAUTIFUL LANEl. -

The Newsletter of the American Pilots' Association

The Newsletter of the American Pilots’ Association December 15, 2017 Page 1 McGEE AND PHILLIPS HONORED FOR HEROISM AT INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION CEREMONY IN LONDON Two Houston Pilots who defied fire to bring a minutes, leaving both pilots exhausted and burned. burning ship to safety, averting a major maritime ca- Captain McGee, using tugs, was then able to bring tastrophe, received the 2017 International Maritime the damaged tanker safely to a mooring facility. Organization (IMO) Award for Exceptional Bravery McGee and Phillips were nominated by the In- at Sea during the 2017 IMO awards ceremony, held ternational Maritime Pilots' Association (IMPA), in London on Monday, November 27. with support from the APA. The Award was decided Captain Michael G. McGee and Captain Mi- by a panel of judges and endorsed by the IMO Coun- chael C. Phillips were recognized for their role in cil at its 118th session in July. averting a major tragedy in September 2016. The Presenting the pilots with medals and certifi- ship the two were piloting, the 810 foot-long tanker cates, IMO Sec- AFRAMAX RIVER, suffered a major propulsion retary General casualty in the middle of the night while in the Hou- Kitack Lim said ston Ship Channel causing the ship to allide with a the two had been mooring dolphin and burst into flames. faced with a Captain McGee and Captain Phillips were sur- challenge which rounded by a towering wall of burning fuel as the was out of the raging fire quickly spread across the channel, threat- ordinary and re- ening other tank ships and nearby waterfront facili- quired great ini- ties. -

Papers of the American Slave Trade

Cover: Slaver taking captives. Illustration from the Mary Evans Picture Library. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Papers of the American Slave Trade Series A: Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society Part 2: Selected Collections Editorial Adviser Jay Coughtry Associate Editor Martin Schipper Inventories Prepared by Rick Stattler A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society [microfilm] / editorial adviser, Jay Coughtry. microfilm reels ; 35 mm.(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Martin P. Schipper, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. Contents: pt. 1. Brown family collectionspt. 2. Selected collections. ISBN 1-55655-650-0 (pt. 1).ISBN 1-55655-651-9 (pt. 2) 1. Slave-tradeRhode IslandHistorySources. 2. Slave-trade United StatesHistorySources. 3. Rhode IslandCommerce HistorySources. 4. Brown familyManuscripts. I. Coughtry, Jay. II. Schipper, Martin Paul. III. Rhode Island Historical Society. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Papers of the American slave trade. Series A, Selections from the Rhode Island Historical Society. VI. Series. [E445.R4] 380.14409745dc21 97-46700 -

Bibliography of Maritime and Naval History

TAMU-L-79-001 C. 2 Bibliographyof Maritime and Naval History Periodical Articles Published 1976-1977 o --:x--- Compiled by CHARLES R. SCHULTZ University Archives Texas A& M University TAMU-SG-79-607 February 1 979 SeaGrant College Program Texas 4& M University Bibliography of Maritime and Naval History Periodical Articles Published 1976-1977 Compiled by Char1es R. Schultz University Archivist Texas ASM University February 1979 TAMU-SG-79-607 Partially supported through Institutional Grant 04-5-158-19 to Texas A&M University by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Sea Grants Department of Commerce Order From: Sea Grant College Program Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION V I ~ GENERAL ~ ~ ~ ~ o ~ ~ t ~ ~ o ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 1 I I . EXPLORATION, NAVIGATION, CARTOGRAPHY. ~ ~ ~ 5 III. MERCHANTSAIL & GENERAL SHIPPING NORTH AMERICA. 11 IV. MERCHANT SAIL & GENERAL SHIPPING OTHER REGIONS. 18 V. MERCHANT STEAM - OCEAN & TIDEWATER, 24 VI. INLAND NAVIGATION 29 VII. SEAPORTS & COASTAL AREAS. 31 VIII. SHIPBUILDING & ALLIED TOPICS. 33 IX. MARITIME LAW. 39 X. SMALL CRAFT 47 XI. ASSOCIATIONS & UNIONS 48 XII. FISHERIES 49 XIII. NAVAL TO 1939 NORTH AMERICA 53 XIV. NAVAL TO 1939 - OTHER REGIONS 61 XV. WORLD WAR II & POSTWAR NAVAL. 69 XVI. MARINE ART, SHIP MODELS, COLLECTIONS & EXHIBITS. 74 XVII. PLEASURE BOATING & YACHT RACING. 75 AUTHOR INDEX 76 SUBJECT INDEX. 84 VESSEL INDEX 89 INTRODUCTION It had been my hope that I would be able to make use of the collec- tions of the G. W. Blunt White Library at Mystic Seaport for this fifth volume as I did for the fourth which appeared in 1976. -

Shipbuilding Catching Shellfish

IntroductionIntroduction Much of the East Riding of Yorkshire adjoins water: the North Sea and the River Humber and its tributaries. Over the centuries men have needed boats to travel over the water and to gather food from under it. Naturally people with the right skills set up to build these boats. Some ship building operations are quite well known, such as those in Beverley and Hull. They have been documented in exhibitions in other local museums. This exhibition looks at some less well known boat building yards and boat builders both on the east coast and along the banks of the Humber. It has been researched and produced by the Skidby Windmill Volunteer Team. Prehistory- the Ferriby boats The Yorkshire Wolds have been home to people since Neolithic times and the River Humber has been an important transport route allowing goods and people to travel in all directions by water. For thousands of years this was the easiest and safest way to travel. It is therefore not surprising that North Ferriby was the site of one of the oldest boatyards in Europe as well as being an important harbour. Above: hypothetical reconstruction of a Ferriby boat. Right: Excavation in 1963 In 1937 changes to the tidal currents exposed three large oak planks preserved in the mud which Ted and Willy Wright recognised as belonging to very early boats. At first these were thought to be Viking but later tests confirmed that they were Bronze Age and, at 4000 years A half-scale replica of the Ferriby boats called Oakleaf has been built and sea trials proved old they are some of the oldest boats discovered in Europe. -

No. 25 the M/V “NORSTAR” CASE (PANAMA V. ITALY) JUDGMENT

INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE LAW OF THE SEA YEAR 2019 10 April 2019 List of Cases: No. 25 THE M/V “NORSTAR” CASE (PANAMA v. ITALY) JUDGMENT 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 1-62 II. Submissions of the Parties 63-68 III. Factual background 69-86 IV. Rules of evidence 87-99 V. Scope of jurisdiction 100-146 The scope of paragraph 122 of the Judgment on Preliminary Objections 109-122 Article 300 of the Convention 123-129 Invocation of article 92 and article 97, paragraphs 1 and 3, of the Convention 130-138 Claim concerning human rights 139-146 VI. Article 87 of the Convention 147-231 The Tribunal’s Judgment on Preliminary Objections 148-152 The activities conducted by the M/V “Norstar” 153-187 Article 87, paragraphs 1 and 2, of the Convention 188-231 VII. Article 300 of the Convention 232-308 Link between article 300 and article 87 of the Convention 232-245 Good faith 246-293 Timing of the arrest of the M/V “Norstar” 248-251 Location of the arrest of the M/V “Norstar” 252-258 Execution of the Decree of Seizure 259-265 Lack of communication 266-271 Withholding information 272-275 Contradictory reasons to justify the Decree of Seizure 276-281 Duration of detention and maintenance of the M/V “Norstar” 282-289 Article 87, paragraph 2, of the Convention 290-293 Abuse of rights 294-308 VIII. Reparation 309-462 Causation 324-370 Causal link 324-335 Interruption of the causal link 336-370 3 Duty to mitigate damage 371-384 Compensation 385-461 Loss of the M/V “Norstar” 394-417 Loss of profits of the shipowner 418-433 Continued payment of wages 434-438 Payment due for fees and taxes 439-443 Loss and damage to the charterer of the M/V “Norstar” 444-449 Material and non-material damage to natural persons 450-452 Interest 453-462 IX. -

Captain John Miller Built Tampa's First Shipyard

Sunland Tribune Volume 7 Article 13 1981 Captain John Miller Built Tampa's First Shipyard Jane Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Smith, Jane (1981) "Captain John Miller Built Tampa's First Shipyard," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 7 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol7/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAPTAIN JOHN MILLER …John's Pass named for him CAPTAIN JOHN MILLER BUILT TAMPA'S FIRST SHIPYARD By JANE (MRS. STOCKTON) SMITH Captain John Miller, pioneer Tampa It is related in Governor Francis P. merchant, ship owner and operator, builder Fleming's Memoirs of Florida that he was of Tampa's first shipbuilding and repair born in Norway, August 4, 1834. At the age yard, had a very interesting history. of 11 he sailed as a cabin boy to Quebec. On CAPE COD'S MELROSE INN ... homestead of Captain Miller reaching Quebec he became an apprentice where he engaged in the summer time in on the American ship Allegheny and served fishing and in the winter was master of a four years learning navigation and boat making West Indies ports. seamanship. During this time the vessel visited ports in all parts of the world; but CIVIL WAR EXPERIENCES those years, though rich in experience and interest, were not correspondingly lucrative At the outbreak of the Civil War Captain for the young boy, as he received no pay for Miller purchased a brig, which was used by his services. -

Maritime Law Now — and Then

Maritime Law NOW – AND THEN Cybersecurity and the Maritime Industry Autonomous Vessels CETA and the Legal Impact on the Canadian Shipping Industry On December 1, 2017, BLG’s Maritime Practice Group hosted some 150 guests at our 29th Annual Maritime Law Seminar. Topics addressed included: • cybersecurity concerns within a global shipping industry in which vessels are increasingly dependent upon systems that rely on digitization, integration and automation and hence, vulnerable to cyber-attacks (vulnerabilities will only increase with the potential introduction of autonomous vessels operating commercially); • the revolutionary impact on all areas of the maritime industry by the inevitable introduction of autonomous vessels; and lastly, • the legal impact on the Canadian shipping industry which flows from the coming into force of CETA, Canada’s trade pact with the European Economic Community (EEC). As in past years, these different topics were introduced by special guest speakers who added real-life insights and experience to the legal framework which BLG provided. The undersigned would like to personally thank our guest speakers, Chris South (West of England P&I Club), Jack Mahoney (Maersk Shipping Lines), Colin Clark (Lloyd’s Register) and Leanne O’Loughlin (Charles Taylor P&I) for their invaluable assistance in contributing to the success of the seminar. In this issue of Maritime Law, we enclose brief articles addressing the above-mentioned seminar topics and trust that you will find them to be informative and thought provoking, and we welcome your feedback and comments. Our current issue also features a “Fireside Chat” with P. Jeremey Bolger – Senior Counsel at BLG, in which Jeremy reflects upon his time as a lawyer and expands upon how the practice of Maritime law has changed and continues to evolve. -

The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Linfield Alumni Book Gallery Linfield Alumni Collections 2019 Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris John Kerr Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerr, John, "Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris" (2019). Linfield Alumni Book Gallery. 1. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books/1 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Book must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers Before the Mast, The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris By John Kerr Carol Lew Simons, Contributing Editor Cover photo by Shep Root Third Edition This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/. 1 PREFACE AND A TRIBUTE TO REGINA Steven Katona Somehow wood, steel, cable, rope, and scores of other inanimate materials and parts create a living thing when they are fastened together to make a ship. I have often wondered why ships have souls but cars, trucks, and skyscrapers don’t.