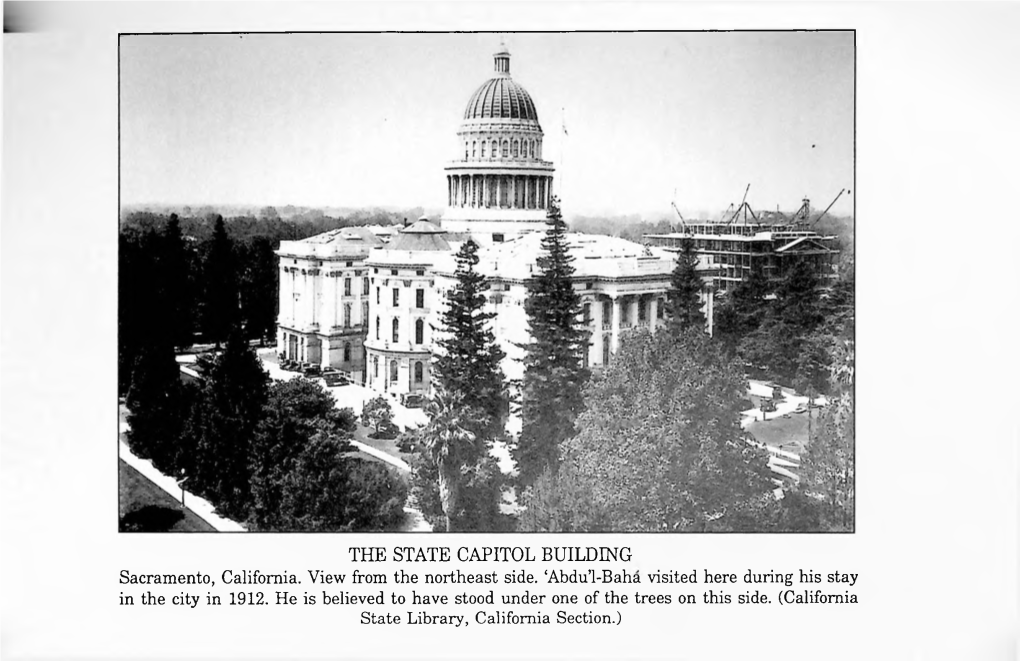

THE STATE CAPITOL BUILDING Sacramento, California. View from the Northeast Side

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the New Thought Movement

RY OF THE r-lT MOVEMEN1 DRESSER I Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO by Victoria College A HISTORY OF THE NEW THOUGHT MOVEMENT BY HORATIO W. DRESSER AUTHOR OF "THE POWER OF SILENCE," * 'HANDBOOK OF THE NEW THOUGHT," "THE SPIRIT OF THE NEW THOUGHT," ETC. NEW YORK THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY PUBLISHERS JUL COPYRIGHT, 1919. BY THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY PREFACE FOR several years there has been a demand for a history of the liberal wing of the mental-healing movement known as the "New Thought." This demand is partly due to the fact that the move- ment is now well organized, with international headquarters in Washington, D. C., hence there is a desire to bring its leading principles together and see in their in to inter- them unity ; and part est in the pioneers out of whose practice the present methods and teachings have grown. The latter interest is particularly promising since the pioneers still have a message for us. Then, too, we are more interested in these days in trac- ing the connection between the ideas which con- cern us most and the new age out of which they have sprung. We realize more and more clearly that this is indeed a new age. Hence we are in- creasingly eager to interpret the tendencies of thought which express the age at its best. In order to meet this desire for a history of the New Thought, Mr. James A. Edgerton, president of the International New Thought Alliance, decided in 1916 to undertake the work. -

1940-04-Unity.Pdf

NITY \PRIL 1940 '15 CE N TS N S E J n Z>L id jQ~ddue ' G od Does the W o r k ............................1 Dana Gatlin God R evealed ............................... 10 Gustave W. Mentz G od a Present H e l p .......................... 12 H. Emilie Cady Be Prospered .................................... 20 Clara Palmer r Hands and W ings .......................... 27 Ernest C. Wilson I t ’s a Poor Rule That W o n ’t W ork Both W a y s .................................... 31 Patricia Nelson A Spiritual Laboratory ..................... 39 An Agnostic Sunday L esson s ............................... 48 Healing & Prosperity T h ou gh ts TO BE USED FROM A P R IL 20 to M A Y 19 H ealing: The joy of Jesus Christ sets me free, and I am healed. AT NINE P. M. EACH DAY CLOSE YOUR EYES AND REPEAT FOR FIFTEEN MINUTES SILENTLY, AND TRY TO REALIZE SPIRITUALLY, THIS HEALING THOUGHT. t Prosperity: I rejoice as I realize Thine all-providing plan now fulfilled in me. AT TWELVE NOON BACH DAY REPEAT FOR FIFTEEN MINUTES, AUDIBLY AND THEN SILENTLY, THIS PROSPERITY THOUGHT. (For an explanation of these thoughts turn to page 68) _________ UNITY______ PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY UNITY SCHOOL OF CHRISTIANITY PUBLICATION, EDITORIAL, AND EXECUTIVE OFFICES I 917 TRACY AVE., KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI Entered as second-class matter, July 15, Accepted for mailing at special rate of 1891, at the post office at Kansas City, postage, provided for in section 1103. act Missouri, under the act of March 3. 1879. of Oct. 3, 1917, authorized Oct. 28. 1922. SINGLE COPIES 15 CENTS—YEARLY SUBSCRIPTION $1 UNITY Devoted, to Christian Healing Charles Fillmore George E. -

The Metaphysical World of Marie Ogden

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2009-11-24 The Home of Truth: The Metaphysical World of Marie Ogden Stanley J. Thayne Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Thayne, Stanley J., "The Home of Truth: The Metaphysical World of Marie Ogden" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 2023. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2023 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Home of Truth: The Metaphysical World of Marie Ogden Stanley James Thayne II A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grant Underwood, Chair Brian Q. Cannon J. Spencer Fluhman Eric A. Eliason Department of History Brigham Young University December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stanley J. Thayne All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Home of Truth: The Metaphysical World of Marie Ogden Stanley J. Thayne Department of History Master of Arts Marie Ogden‘s Home of Truth colony—a religious community that was located in southern Utah during the 1930s and 40s—was part of a segment of the American religious landscape that has largely been overlooked. As such, her movement points to a significant gap in the historiography of American religion. In addition to documenting the history of this obscure community, I situate Marie Ogden as part of what I call the early new age of American religion, an underdeveloped part of the broader categories of metaphysical religion or Western esotericism. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries. -

Sas Qty, Mo., November, 1902

HEW inc. VD KANSAS QTY, MO., NOVEMBER, 1902. No. 5. CONTENTS, PAGK I Arn Myself 259 By Annie Rix Militz. The Power of Thought. 262 By Jeanie P. Owens. Bible Lessons. 268 'f^fj By Leo Virgo. Concerning the Praise Treatment. 276 By Fannie M. Harley. yf Kansas City Mid-Week Reports. 282 Society of Silent Unity. 286 The Class Thought 287 Noon Thought 287 . Chicago Reports 288 Answers to Questions. 295 By Jennie H. Croft. **H^[ Thinking 297 By H. Emilie Cady. k . i Publishers' Department. 309 ^**L Review of New Books. ... \\ j By J. H. C. sa - — :t=$ 0 ~ ry.- •-. - Mcfiet ST UNITY TRACTSOCIETY KANSAS CITY, MO EUROPE: Geo. Osbond, Devonport, Devon, England. '--"~VW -KANSAS (3 En ,and yGoogb * - ANNOUNCEMENT UNITY is a band-book of Practical Christianity and Christian Healing It sets forth the pure doctrine of Jesus Christ direct from the fountain-head, "The Holy Spirit, who will lead you into all Truth" It is not the organ of any sect, but stands independent as an exponent of Practical Christianity, teaching the practical application in all the affairs of life of the doctrine of Jesus Christ; explaining the action of mind, and how it is the connecting link between God and man; how mind action affects the body, produc- ing discord or harmony, sickness or health, and brings man into the understanding of Divine Law, harmony, health and peace, here and now Subscribers who fail to receive UNITY by the 20th of the month, should so notify this office. If you have subscribed for any other magazine in connection with UNITY, and should miss any number of that magazine, do not write us about it, but write directly to its publisher. -

Keelers Comments V6 N7 Jul 1938

NO. 7 .. 6 IfiHI PKPOSir £ ml J 1 ill'.!i 1 ll'1. ! hi. I I i't; t 1 I f IS l _ 1 I 1 1 Ll liM □ n % SPIRIT - BODY - MIKT©*j*J */ i.i/ HEALING A CASE PRE-EXISTING CAUSE TRUTH - TO - ME j □ T] U L y B 1.00 the year. I 0 <t the copy. oci m DOMINUS ILLUMINATI0 MEA KE E L ER'S JULY 1938 C O jy] jVl £ N T About Applied Christianity, the Victorious Faith, Direct Knowing (Intuition) and the Greater Power of the Spiritual Empire of the Mind. An unique periodical published by W. FREDERIC KEELER. For those who wish to know the Truth of the Indwelling Christ. ISSUED the first of each month. SUBSCRIPTION: One dollar a year. Six months, fifty cents. Ten cents each post free when mailed separately. Special rates to Centers, Libraries and Bookshops. SAMPLES WILL BE MAILED TO SUBSCRIBERSJ FRIENDS. COPYRIGHT: W. F. Keeler, 1938 Certified copyright privileges to approved students, teachers, and ministers. CONTENTS Spirit is Body, Body is Spirit - Mind is Both....................Page 4 Using New Ideas by Rev. Betty Irene Miller.... .......... .... 6 Substituting for God................................................................................... 7 Just a Talk About Healing a Case .................................. ........................ 9 A Prayer..............................................— .......—......................— .....— I 4 Pre-Existing Cause Is C a u se ................................................................ 15 Some Truth-to-me .......................—...................................-........-..—.........- I I Correspondences.........................................-..........................—....-...........— 2 I New Lessons ........_..........................................- ...................._ ....... 23 A Chat About Fees _____________— ...................................— ---------------- 24 For inf or mat i on concerning PERSONAL SERVICES write W. FREDERIC KEELER, P. 0. BOX 426, SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA Keeler 1 s Comme nts SPIRIT IS BODY o BODY IS SPIRIT MIND IS BOTH THE LAST SUPPER Hark 14:22 - 25 and Matt. -

Nautilus V10 N5 Mar 1908

In this Number: THE HABIT OF BEAUTY. See Table Contents, Page 5. P R i n r 1 o _ r r g THE NAUTILUS. iinm m H m m uiinTnnmU'J WONDERFUL FREE TRIAL OFFER OF THE VIBRO-LIFE THE LATEST, GREATEST VIBRATOR. NO ELECTRICITY. THE OKLY' HAND-OPERATED VIBRATOR WITH INTERCHANGEABLE, FACIAL, BODY AND SCALP APPLICATIONS. REMOVING WRINKLES FOR INDIGESTION Gives 500 to 50,000 Delightful and Effective Vibrations per Minute W omen remove wrinkles, double chin, baggy cheeks, etc., develop neck and bust, restore Complexion of youth and massage the scalp. Men massage after shaving, prevent baldness, relieve pain, indigestion, constipation, headaches, sleeplessness, rheumatism, deafness and nervousness. VIBRATION IS NOW RECOGNIZED the world over as the great est aid to health and beauty available. It promotes beauty and restores health by increasing the circulation of the blood to the part massaged. It is local exercise which builds up weak and scrawny tissues and distributes deposits of excess fat. You can perfect your face or figure to suit their needs, stop all pains due to congestion, inflammation of superficial muscles or irritated nerves and secure instant relief and per manent improvement in many ailments difficult to cure by ordinary means. VIBRO-LIFE VIBRO-LIFE USES NO ELECTRICITY WTTTT \ p p t irA Tnuc an^ can operated by a child, merely by turning the crank. Through LiL-AiUKb a marvelously simple invention, one turn of the handle yields 100 vibra- . tions, two turns a second yields 12,000 vibrations a minute. Nothing to get out of order, no expense for batteries or electric current. -

Both Riches and Honor (Formerly "Prosperity")

Both Riches and Honor (formerly "Prosperity") By Annie Rix Militz. first published in 1945 A Unity Public Domain Book "Knowledge should be told, not sold" Charles Fillmore For a time, Annie went out to Missouri and worked with Charles Fillmore developing the Unity Branch of New Thought, but eventually she returned to California expanding the Home of Truth. The main Home of Truth still exists today. Global New Thought is working actively with Home of Truth to place all of Militz' texts online to facilitate online studies of this rich and wonderful New Thought denomination. This book was one of her many contributions to the Unity Movement. Prosperity through Spirituality CHAPTER I Both riches and honor come of you, and you rule over all; and in your hand is power and might; and in your hand it is to make great, and to give strength unto all. IT IS NOW ESTABLISHED in the minds of many people that health of body is a legitimate result of spiritual knowledge and eventually will be one of the signs of a practical follower of Christ; but these same people, many of them, find it difficult to believe that health of circumstances can be demonstrated in the same way and is as legitimate and true a sign of the understanding of spiritual law as the healing of the body. Considering riches with a fair, unprejudiced mind, we shall understand why it is that they have been largely in the possession of the unspiritual instead of the children of God, to whom the heritage rightly belongs. -

A History of the New Thought Movement by Horatio W. Dresser

A History of the New Thought Movement by Horatio W. Dresser Published by Thomas Y. Crowell Co., New York 1919 This ebook (c) MK Cultra 2006 mkcultra.com Chapter 1 - THE NEW AGE THE great war came as a vivid reminder that we live in a new age. We began to look back not only to explain the war and find a way to bring it to an end, but to see what tendencies were in process to lead us far beyond it. There were new issues to be met and we needed the new enlightenment to meet them. The war was only one of various signs of a new dispensation. It came not so much to prepare the way as to call attention to truths which we already possessed. The new age had been in process for some time. Different ones of us were trying to show in what way it was a new dispensation, what principles were most needed. What the war accomplished for us was to give us a new contrast. As a result we now see clearly that some of the tendencies of the nineteenth century which were most warmly praised are not so promising as we supposed. We had come to regard the nineteenth century as the age of the special sciences. We looked to science for enlightenment. We enjoyed new inventions without number, such as the steam-engine, the electric telegraph, the telephone, and our life centered more and more about these. But the nation having most to do with preparation for the war was the one which made the greatest use of the special sciences. -

Dr. /£ Bmilie Cady I

Dr. _/£ Bmilie Cady I. N. T. A. EXECUTIVE BOARD Officers DR. RAYMOND C. BARKER 58 West 57th Street New York 19, New York 1 st Vice-President Secretary (headquarters) i DR. JAMES E. DODDS MISS FLORENCE E. FRISBIE Academy of Spiritual Science 1713 KSt. N. W. 43 North Euclid Avenue Pasadena 1, California Washington 6, D. C. 2nd Vice-President REV. EMMA SMILEY Victoria Truth Center Treasurer 734 Fort Street Victoria, B. C, Canada MISS IDA JANE AYRES 1601 Argonne Place N. W. 3rd Vice-President REV. ELIZABETH CARRICK-COOK Washington 9, D. C. Institute of Religious Science 177 Post Street San Francisco 8, Calif. Auditor 4th Vice-President REV. ELEANOR MEL DR. FLORRIE BEAL CLARK Boston Home of Truth 209 APCO Tower Building Oklahoma College of Divine Science 175 Commonwealth Avenue Oklahoma City 2, Oklahoma Boston 16, Massachusetts Board Members Three-Year Term REV. MAEBEL V. CARRELL DR. FLETCHER A. HARDING Unity Church of Christ Associate Minister 1322 South Fourth Street School of Psychology and Divine Science Louisville 8, Kentucky One Groveland Ter., Minneapolis 5, Minn. Two-Year Term REV. MAUDE ALLISON LATHEM REV. RUTH CHEW Institute of Religious Science Church of the Truth 3251 West Sixth Street 810-A First Street, West Los Angeles 5, California Calgary, Alberta, Canada One-Year Term DR. AMELIA A. RANDALL REV. ERVIN SEALE New Life Fraternity Church of the Truth 2744 Fourth Avenue South 9 East 40th Street Minneapolis 8, Minnesota New York 16, New York Poet haureate of the 1. N. T. A. REV. HENRY VICTOR MORGAN Past Presidents REV. -

Nautilus V45 N12 Oct 1943

NAUTILUS MAGAZINE I Important to What's Cooking Nautilus Subscribers FOR NEXT MONTH? If you find an expiration notice attached to this space it m<:>ans that your subscription expires with this issue UNLESS your ren ewa l has crossed the notice in the mail. IF YOU WILL RETURN THE RENEWAL Since the prize article was How to Use BLANK WITH YOUR REMITTANCE SO THAT published m June NAUTILUS IT REACHES US BY THE 2oth OF THE MONTH Subconscious Miss Hazel Dean has received OF THIS ISSUE WE WILL CREDIT YOU WITH Power 13 MONTHS FOR $2.00. Extra month for prompt many letters and inquiries renewal. Or we will send NAUTILUS two years for asking for fu rther details on just how the dem $3.00 (3oc extra per year for Canadian postage; and onstrations she described were brought about. 6oc extra postage per year to foreign lands.) So, she has wri teen a compact little course of W E AFFIRM that the basic tr.;th of all relig three lessons on ··How We Made Our Dreams ions is one. And that this truth- ""derstood alld Come True." The first lesson starts with "How applied-frm, heals and prospers the individ11al We Began," and gives the theory by which -HERE AND NOW. they worked, namely, that there is a power in everyone that can do whatever we ask of it. NAuTILUS takes its name from the following verse "This power is as real as electricity, as real as from Holmes' poem, The Chambered Nautilus: your shoes, as real as the bread you put into BuiLD thee more stately mansions, oh, my soul, your mouth," she says. -

The Romance of Metaphysics

THE ROMANCE OF METAPHYSICS --------------------------------------------------- AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY, THEORY AND PSYCHOLOGY OF MODERN METAPHYSICS ~•~ By ISRAEL REGARDIE --------------------------------------------------- 1 "Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it. "Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain." (Psalm 127.) "Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus." (Phil. 2, v. 5-6.) 2 I dedicate this book to DOROTHY 3 -------------------------------------------------------------- F O R E W O R D -------------------------------------------------------------- THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN BEFORE THE WAR. Completed some months before I entered in the armed forces early in 1942, the manuscript has been in storage ever since. It was written primarily to establish certain points of relationship between the various metaphysical schemes and fundamental concepts of modern psychology. It has a sort of tentative personal meaning. Possibly a great deal more by way of synthesis could be acomplished to-day, with increased experience and knowledge of what psychiatry and psychoanalysis represent. However, I have decided to let the manuscript remain in its present form, unaltered and unmodified, since it was a spontaneous creative effort and may therefore serve some useful purpose to other students. Throughout, I have been moved by a sense of what I conceived to be fairness to the metaphysical schemes described. I have tried to avoid harsh prejudiced criticism. Nor have I gone too deeply into basic psychological concepts of the growth and structure of the psyche and the dynamic mechanisms it daily employs. However, such concepts are implicit in all the comments ventured in the different parts of the work.