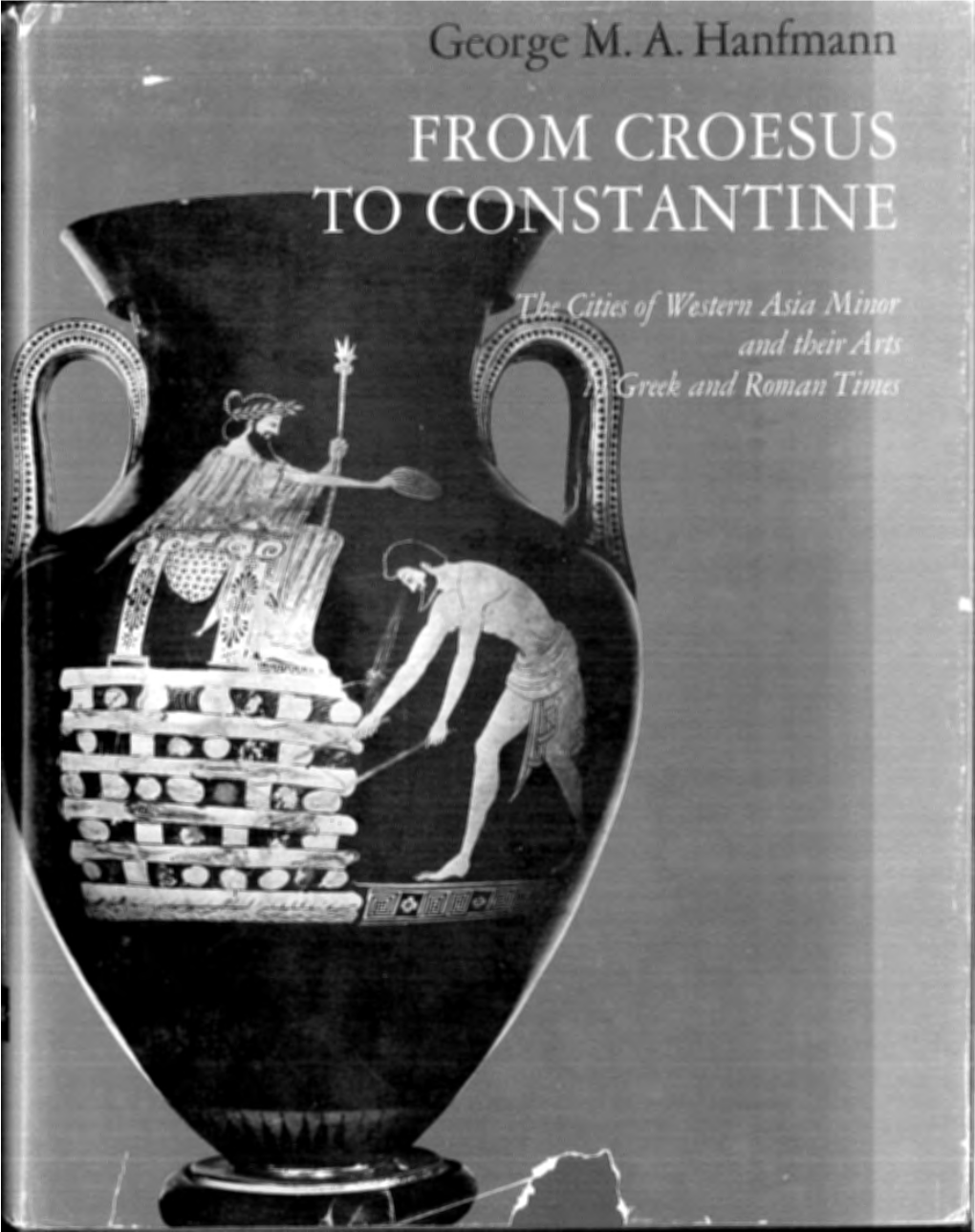

Hanfmann, from Croes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Gorgon-Medousa Artwork in Ancient Hellenic World

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 5, No. 1, (2019), pp. 1-14 Open Access. Online & Print DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1451898 GOLDEN GORGON-MEDOUSA ARTWORK IN ANCIENT HELLENIC WORLD Lazarou, Anna University of Peloponnese, Dept of History, Archaeology and Cultural Resources Management Palaeo Stratopedo, 24100 Kalamata, Greece ([email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 15/06/2018 Accepted: 25/07/2018 ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to highlight some characteristic examples of the golden works depicting the gorgoneio and Gorgon. These works are part of the wider chronological and geographical context of the ancient Greek world. Twenty six artifacts in total, mainly jewelry, as well as plates, discs, golden bust, coins, pendant and a vial are being examined. Their age dates back to the 6th century. B.C. until the 3rd century A.D. The discussion is about making a symbol of the deceased persist for long in the antiquity and showing the evolution of this form. The earliest forms of the Gorgo of the Archaic period depict a monster demon-like bellows, with feathers, snakes in the head, tongue protruding from the mouth and tusks. Then, in classical times, the gorgonian form appears with human characteristics, while the protruded tusks and the tongue remain. Towards Hellenistic times and until late antiquity, the gorgoneion has characteristics of a beautiful woman. Snakes are the predominant element of this gorgon, which either composes the gargoyle's hairstyle or is plundered like a jewel under its chin. This female figure with the snakes is interwoven with Gorgo- Medusa and the Perseus myth that had a wide reflection throughout the ancient times. -

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo Myfreebingocards.Com

Greek Myths - Creatures/Monsters Bingo myfreebingocards.com Safety First! Before you print all your bingo cards, please print a test page to check they come out the right size and color. Your bingo cards start on Page 3 of this PDF. If your bingo cards have words then please check the spelling carefully. If you need to make any changes go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Play Once you've checked they are printing correctly, print off your bingo cards and start playing! On the next page you will find the "Bingo Caller's Card" - this is used to call the bingo and keep track of which words have been called. Your bingo cards start on Page 3. Virtual Bingo Please do not try to split this PDF into individual bingo cards to send out to players. We have tools on our site to send out links to individual bingo cards. For help go to myfreebingocards.com/virtual-bingo. Help If you're having trouble printing your bingo cards or using the bingo card generator then please go to https://myfreebingocards.com/faq where you will find solutions to most common problems. Share Pin these bingo cards on Pinterest, share on Facebook, or post this link: mfbc.us/s/xs25j Edit and Create To add more words or make changes to this set of bingo cards go to mfbc.us/e/xs25j Go to myfreebingocards.com/bingo-card-generator to create a new set of bingo cards. Legal The terms of use for these printable bingo cards can be found at myfreebingocards.com/terms. -

Scientific Programme 9Th FORUM on NEW MATERIALS

9th Forum on New Materials SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME 9th FORUM ON NEW MATERIALS FA-1:IL09 Clinical Significance of 3D Printing in Bone Disorder OPENING SESSION S. BOSE, School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Department of Chemistry, Elson Floyd College of Medicine, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA WELCOME ADDRESSES FA-1:IL10 Additive Manufacturing of Implantable Biomaterials: Processing Challenges, Biocompatibility Assessment and Clinical Translation Plenary Lectures B. BASU, Materials Research Centre & Center for BioSystems Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India F:PL1 Organic Actuators for Living Cell Opto Stimulation FA-1:IL11 Synthesis and Additive Manufacturing of Polycarbosilane G. LANZANI, Center for Nano Science and Technology@PoliMi, Istituto Systems Italiano di Tecnologia, and Department of Physics, Politecnico di Milano, K. MARtin1,2, L.A. Baldwin1, T.PatEL1,3, L.M. RUESCHHOFF1, C. Milano, Italy WYCKOFF1,4, J.J. BOWEN1,2, M. CINIBULK1, M.B. DICKERSON1, 1Materials F:PL2 New Materials and Approaches and Manufacturing Directorate, Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright- R.S. RUOFF, Ulsan National Institute of Science & Technology (UNIST), Patterson AFB, OH, USA; 2UES Inc., Dayton, OH, USA; 3NRC Research Ulsan, South Korea Associateship Programs, Washington DC, USA; 4Wright State University, Fairborn, OH, USA F:PL3 Brain-inspired Materials, Devices, and Circuits for Intelligent Systems FA-1:L12 Extending the Limits of Additive Manufacturing: Emerging YONG CHEN, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA Techniques to Process Metal-matrix Composites with Customized Properties A. SOLA, A. TRINCHI, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Australia, Manufacturing Business Unit, Metal Industries Program, Clayton, Australia SYMPOSIUM FA FA-1:L13 Patient Specific Stainless Steel 316 - Tricalcium Phosphate Biocomposite Cellular Structures for Tissue Applications Via Binder Jet Additive Manufacturing 3D PRINTING AND BEYOND: STATE- K. -

The Synopsis of the Genus Trigonella L. (Fabaceae) in Turkey

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2020) 44: 670-693 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-2004-63 The synopsis of the genus Trigonella L. (Fabaceae) in Turkey 1, 2 2 Hasan AKAN *, Murat EKİCİ , Zeki AYTAÇ 1 Biology Department, Faculty of Art and Science, Harran University, Şanlıurfa, Turkey 2 Biology Department, Faculty of Science, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey Received: 25.04.2020 Accepted/Published Online: 23.11.2020 Final Version: 30.11.2020 Abstract: In this study, the synopsis of the taxa of the genus Trigonella in Turkey is presented. It is represented with 34 taxa in Turkey. The name of Trigonella coelesyriaca was misspelled to Flora of Turkey and the correct name of this species, Trigonella caelesyriaca, was given in this study. The endemic Trigonella raphanina has been reduced to synonym of T. cassia and T. balansae is reduced to synonym of T. corniculata. In addition, T. spruneriana var. sibthorpii is reevaluated as a distinct species. Lectotypification was designated forT. capitata, T. spruneriana and T. velutina. Neotypification was decided for T. cylindracea and T. cretica species. Trigonella taxa used to be represented by 52 taxa in the Flora of Turkey. However, they have later been evaluated by different studies under 32 species (34 taxa) in Turkey. In this study, taxonomic notes, diagnostic keys are provided and general distribution as well as their conservation status of each species within the genus in Turkey is given. Key words: Anatolia, lectotype, Leguminosae, neotype, systematic 1. Introduction graecum L. (Fenugreek) were known and used for different The genus Trigonella L. -

Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC

European Journal of Archaeology 20 (1) 2017, 120–147 This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Story of a Forgotten Kingdom? Survey Archaeology and the Historical Geography of Central Western Anatolia in the Second Millennium BC 1,2,3 1,3 CHRISTOPHER H. ROOSEVELT AND CHRISTINA LUKE 1Department of Archaeology and History of Art, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 2Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç University, I˙stanbul, Turkey 3Department of Archaeology, Boston University, USA This article presents previously unknown archaeological evidence of a mid-second-millennium BC kingdom located in central western Anatolia. Discovered during the work of the Central Lydia Archaeological Survey in the Marmara Lake basin of the Gediz Valley in western Turkey, the material evidence appears to correlate well with text-based reconstructions of Late Bronze Age historical geog- raphy drawn from Hittite archives. One site in particular—Kaymakçı—stands out as a regional capital and the results of the systematic archaeological survey allow for an understanding of local settlement patterns, moving beyond traditional correlations between historical geography and capital sites alone. Comparison with contemporary sites in central western Anatolia, furthermore, identifies material com- monalities in site forms that may indicate a regional architectural tradition if not just influence from Hittite hegemony. Keywords: survey archaeology, Anatolia, Bronze Age, historical geography, Hittites, Seha River Land INTRODUCTION correlates of historical territories and king- doms have remained elusive. -

Pisidia Bölgesi'nde Seleukoslar Dönemi Yerleşim Politikaları1

Colloquium Anatolicum 2015 / 14 s. 160-179 TEBE KONFERANSI Pisidia Bölgesi’nde Seleukoslar Dönemi Yerleşim Politikaları1 Bilge HÜRMÜZLÜ2 |160| 1 Hakeme Gönderilme Tarihi: 30.11.2015; kabul tarihi: 09.12.2015. 2 Bilge HÜRMÜZLÜ, Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi, Fen Edebiyat, Arkeoloji Bölümü, TR 32600 ISPARTA; [email protected]. Keywords: Seleucid, Apollonia, Seleukeia, Antiokheia, Neapolis At the end of the Ipsos War (301 bc), Antigonos was definitely defeated; and his territory was shared by the allies, Lysimakhos, Seleucia and Ptolemaios. The Seleucid dominance in the area became definite, as generally accepted, with the Curupedion War (281 bc). Even though the established Seleucid Dynasty brought an end to the Diadochi Wars, it is understood that power struggles continued in the region for many more years as a result of the Galatian invasions that took place in different periods, further wars and insurgencies (Özsait 1985: 45-51; Vanhaver- beke – Waelkens 2005: 49-50). In the broadest sense, Seleucids ruled their land through a wise policy where they allowed local people to implement their own policies in daily affairs, and as we encounter numerous samples in several territories they ruled, they founded significant colonies at strategically important sites in the northern Pisidia. These colonies were located at geopolitically critical places where they could control road and trade networks of Phrygia and Lycia-Pamphy- lia. Within the borders of Pisidian Region, there were four colony cities (Antiocheia, Apollonia, Seleucia and Neapolis), which were probably established in different periods. Apart from the |161| poleis founded during the rule of Seleucids, it was discovered in the field studies that there were relatively smaller settlements in the area, some of which even date back to earlier periods. -

I. Türkiye Derin Deniz Ekosistemi Çaliştayi Bildiriler Kitabi 19 Haziran 2017

I. TÜRKİYE DERİN DENİZ EKOSİSTEMİ ÇALIŞTAYI BİLDİRİLER KİTABI 19 HAZİRAN 2017 İstanbul Üniversitesi, Su Bilimleri Fakültesi, Gökçeada Deniz Araştırmaları Birimi, Çanakkale, Gökçeada EDİTÖRLER ONUR GÖNÜLAL BAYRAM ÖZTÜRK NURİ BAŞUSTA Bu kitabın bütün hakları Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı’na aittir. İzinsiz basılamaz, çoğaltılamaz. Kitapta bulunan makalelerin bilimsel sorumluluğu yazarlarına aittir. All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission from the Turkish Marine Research Foundation. Copyright © Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı ISBN-978-975-8825-37-0 Kapak fotoğrafları: Mustafa YÜCEL, Bülent TOPALOĞLU, Onur GÖNÜLAL Kaynak Gösterme: GÖNÜLAL O., ÖZTÜRK B., BAŞUSTA N., (Ed.) 2017. I. Türkiye Derin Deniz Ekosistemi Çalıştayı Bildiriler Kitabı, Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı, İstanbul, Türkiye, TÜDAV Yayın no: 45 Türk Deniz Araştırmaları Vakfı (TÜDAV) P. K: 10, Beykoz / İstanbul, TÜRKİYE Tel: 0 216 424 07 72, Belgegeçer: 0 216 424 07 71 Eposta: [email protected] www.tudav.org ÖNSÖZ Dünya denizlerinde 200 metre derinlikten sonra başlayan bölgeler ‘Derin Deniz’ veya ‘Deep Sea’ olarak bilinir. Son 50 yılda sualtı teknolojisindeki gelişmelere bağlı olarak birçok ulus bu bilinmeyen deniz ortamlarını keşfetmek için yarışırken yeni cihazlar denemekte ayrıca yeni türler keşfetmektedirler. Özellikle Amerika, İngiltere, Kanada, Japonya başta olmak üzere birçok ülke derin denizlerin keşfi yanında derin deniz madenciliğine de ilgi göstermektedirler. Daha şimdiden Yeni Gine izin ve ruhsatlandırma işlemlerine başladı bile. Bütün bunlar olurken ülkemizde bu konuda çalışan uzmanları bir araya getirerek sinerji oluşturma görevini yine TÜDAV üstlendi. Memnuniyetle belirtmek gerekir ki bu çalıştay amacına ulaşmış 17 değişik kurumdan 30 uzman değişik konularda bildiriler sunarak konuya katkı sunmuşlardır. -

Periodic Reporting Cycle 1, Section I

Application of the World Heritage Convention by the States Parties City of Rhodes (1988); Mystras, (1989); GREECE Archaeological Site of Olympia (1989); Delos (1990); Monasteries of Daphni, Hossios Luckas and Nea Moni of Chios (1990); Pythagoreion and I.01. Introduction Heraion of Samos (1992); Archaeological Site of Vergina (1996); Archaeological Sites of Mycenae Year of adhesion to the Convention: 1981 and Tiryns (1999); The Historic Centre (Chorá) with the Monastery of Saint John “the Theologian” and the Cave of Apocalypse on the Island of Organisation(s) or institution(s) responsible for Pátmos (1999) preparation of report • 2 mixed (cultural and natural) sites: Mount Athos (1988); Meteora (1988) • Ministry of Culture, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage Benefits of inscription I.02. Identification of Cultural and Natural • Honour/prestige, enhanced protection and Properties conservation of the site, working in partnership, lobbying and political pressure, endangered site protected Status of national inventories • The coordinating unit of national cultural heritage I.05. General Policy and Legislation for the inventories is the Directorate of the Archive of Protection, Conservation and Monuments and Publications/ Ministry of Culture Presentation of the Cultural and Natural • Natural Heritage has no central inventory because Heritage responsibility is divided between several ministries • Scientific List of Protected Areas related to the NATURA 2000 requirements Specific legislations • Cultural environment: Law ‘On the protection of I.03. The Tentative List Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in General’. The ‘General Building Construction Regulation’ focuses • Original Tentative List submitted in 1985 specially on the protection of listed architectural • Revision submitted in 2003 heritage and living settlements. -

Guidelines for Handouts JM

UCL - INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL3034 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF EARLY ANATOLIA 2007/2008 Year 3 Option for BA Archaeology 0.5 unit Co-ordinator: Professor Roger Matthews [email protected] Room 411. Tel: 020 7679 7481 UCL students at the Iron Age site of Kerkenes, June 2006 1 AIMS To provide an introduction to the archaeology of early Anatolia, from the Palaeolithic to the Iron Age. To consider major issues in the development of human society in Anatolia, including the origins and evolution of sedentism, agriculture, early complex societies, empires and states. To consider the nature and interpretation of archaeological sources in approaching the past of Anatolia. To familiarize students with the conduct and excitement of the practice of archaeology in Anatolia, through an intensive 2-week period of organized site and museum visits in Turkey. OBJECTIVES On successful completion of this course a student should: Have a broad overview of the archaeology of early Anatolia. Appreciate the significance of the archaeology of early Anatolia within the broad context of the development of human society. Appreciate the importance of critical approaches to archaeological sources within the context of Anatolia and Western Asia. Understand first-hand the thrill and challenge of practicing archaeology in the context of Turkey. COURSE INFORMATION This handbook contains the basic information about the content and administration of the course. Additional subject-specific reading lists and individual session handouts will be given out at appropriate points in the course. If students have queries about the objectives, structure, content, assessment or organisation of the course, they should consult the Course Co-ordinator. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

EA Index1-44

EPIGRAPHICA ANATOLICA Zeitschrift für Epigraphik und historische Geographie Anatoliens Autoren- und Titelverzeichnis 1 (1983) – 44 (2011) Adak, M., Claudia Anassa – eine Wohltäterin aus Patara. EA 27 (1996) 127–142 – Epigraphische Mitteilungen aus Antalya VII: Eine Bauinschrift aus Nikaia. EA 33 (2001) 175–177 Adak, M. – Atvur, O., Das Grabhaus des Zosimas und der Schiffseigner Eudemos aus Olympos in Lykien. EA 28 (1997) 11–31 – Epigraphische Mitteilungen aus Antalya II: Die pamphylische Hafenstadt Magydos. EA 31 (1999) 53–68 Akar Tanrıver, D., A Recently Discovered Cybele Relief at Thermae Theseos. EA 43 (2010) 53–56 Akar Tanrıver, D. – Akıncı Öztürk, E., Two New Inscriptions from Laodicea on the Lycos. EA 43 (2010) 50–52 Akat, S., Three Inscriptions from Miletos. EA 38 (2005) 53–54 – A New Ephebic List from Iasos. EA 42 (2009) 78–80 Akat, S. – Ricl, M., A New Honorary Inscription for Cn. Vergilius Capito from Miletos. EA 40 (2007) 29–32 Akbıyıkoğlu, K. – Hauken, T. – Tanrıver, C., A New Inscription from Phrygia. A Rescript of Septimius Severus and Caracalla to the coloni of the Imperial Estate at Tymion. EA 36 (2003) 33–44 Akdoğu Arca, E., Epigraphische Mitteilungen aus Antalya III: Inschriften aus Lykaonien im Museum von Side. EA 31 (1999) 69–71 Akıncı, E. – Aytaçlar, P. Ö., A List of Female Names from Laodicea on the Lycos. EA 39 (2006) 113– 116 Akıncı Öztürk, E. – Akar Tanrıver, D., Two New Inscriptions from Laodicea on the Lycos. EA 43 (2010) 50–52 Akıncı Öztürk, E. – Tanrıver, C., New Katagraphai and Dedications from the Sanctuary of Apollon Lairbenos.