Beginning of Part TWO...IA-QRP Journal, May 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

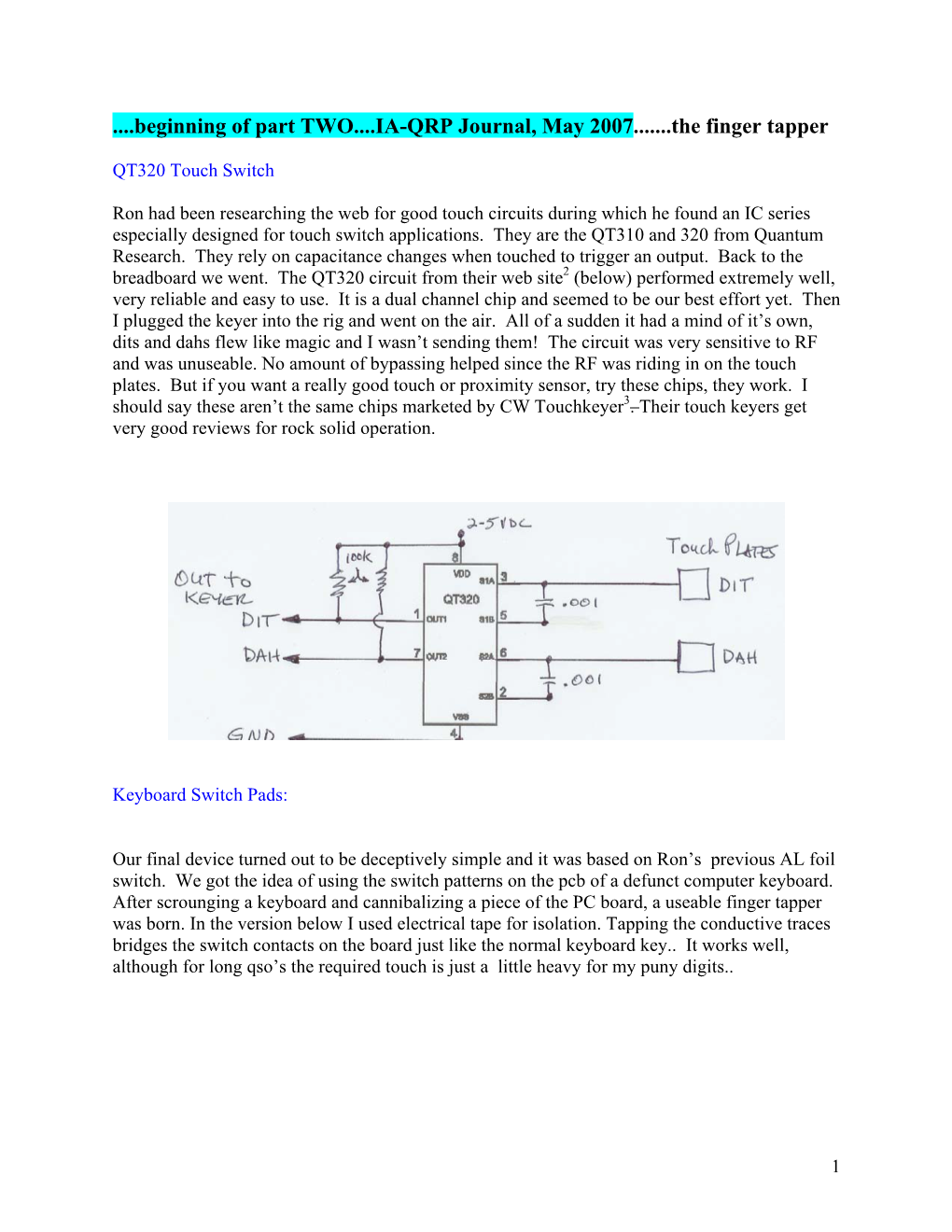

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QRP Notes and Definitions Page 1 Philosophy Practice QRSS

QRP notes and definitions Page 1 QRP operation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In amateur radio, QRP operation means transmitting at reduced power levels while aiming to maximize one's effective range while doing so. The term QRP derives from the standard Q code used in radio communications, where "QRP" and "QRP?" are used to request, "Reduce power", and ask "Should I reduce power?" respectively. The opposite of QRP is QRO, or high-power operation. Philosophy Most amateurs use approximately 100 watts on HF and 50 watts on VHF/UHF, but in some parts of the world, like the US, they can use up to 1500 watts. QRP enthusiasts contend that this is not always necessary, and doing so wastes power, increases the likelihood of causing interference to nearby televisions, radios, and telephones. A lot of Amateurs subscribe to the idea, use "the minimum power necessary to carry out the desired communications". The current record for a QRP connection is 1 µW for 1,650 miles on 10m. Practice There is not complete agreement on what constitutes QRP power. While most QRP enthusiasts agree that for CW, AM, FM, and data modes, the transmitter output power should be 5 watts (or less), the maximum output power for SSB (single sideband) is not always agreed upon. Some believe that the power should be no more than 10 watts peak envelope power (PEP), while others strongly hold that the power limit should be 5 watts. QRPers are known to use even less than five watts, sometimes operating with as little as 100 milliwatts or even less. -

QRP Contesting and Dxing K6UFO - Mark “Mork” Aaker

QRP Contesting and DXing K6UFO - Mark “Mork” Aaker QRP LOW Power HIGH Power “QRP” is an old telegraph signal: “lower your power.” QRP? = Can you lower your power? Today, the standard Amateur Radio meanings are : • QRP = 5 Watts or less transmitter power. • Low Power = up to 100 Watts, e.g., a “barefoot” radio. (up to 150 Watts in ARRL contests) • High Power “QRO”, from 100 W (or 150 W) up to the contest limit (1,500 W) or the country’s legal limit. Canada: 2,250 W PEP USA 1,500 W Japan: 1,000 W Italy: 500 W U.K.: 400 W Oman: 150 W How MUCH Power? • Total Energy Output of the Sun 10^26 W • Nuclear reactor 1 Gigawatt = 10^9 W • Shortwave Broadcast 1 Megawatt = 10^6 W • AM/FM radio Broadcast 50,000 W • Digital TV Broadcast 10,000 W • Amateur Radio 1,500 W • Microwave oven 1,000 W @ 2.45 GHz How little Power? • Amateur Radio 1,500 W – 100 W – 5 W • Christmas tree bulb 7 W – 5 W • CB Radio 4 W • LED Flashlight 3 W – 1W • Cell phone 2 W - 0.002 Watt • FRS radio 500 milliwatt • WiFi transmitter 100 milliwatt – 0.1 mW • Equivalent light output of a Firefly 1 mW It’s the Law! …as far as I can tell, no Amateur has ever been cited. Let’s get this out of the way, Can QRP really work? ARRL Field Day 2012: #3 highest score, station K6EI, 2,827 contacts, 5 watts. #5 highest score, station W5YA , 1,937 contacts, 5 watts. -

World of QRP

World of QRP Tino Zottola, VE2GCE August 17, 2020 Agenda • Introduction • Operation • QRP History • Classic QRP radios • Common Architecture • Modern kits • Antennas • Challenges & Solutions • Conclusion Tino Zottola, VE2GCE, Aug 17, 2020 Introduction What is the appeal of QRP ? 1. Challenge: Long distance communication with the power of flashlight batteries. 2. Simplicity: Most QRP equipment is a kit / homebrewed and is easy to operate User knows function of each component. 3. Nostalgia: Reliving the old days when contacts were made with primitive equipment and each contact was an achievement. Tino Zottola, VE2GCE, Aug 17, 2020 Definition QRP = “Reduce power“ QRP enthusiast’s goal ➔ Use minimum power possible to carry out the desired communications The difference between 100 watts and 1 watt is only 20 dB or (3.3 S units) • 5 Watts (max) CW /FT8 • 10 Watt (max) SSB QRPp (extreme QRP): Sub-watt region • Using 100 milliwatts, 10 milliwatts or 1 milliwatt Commonly used benchmark is ratio of distance / power • Montreal - Charleston, SC: 1000 miles with 1000 watts ➔ 1 mile / watt • Montreal - Charleston, SC: 1000 miles with 1 watt ➔ 1000 miles / watt • Montreal - Eastern Australia: 10000 miles with 1 watt ➔ 10,000 miles / watt • Montreal - Eastern Australia: 10000 miles with 0.001 watt ➔ 10,000,000 miles / watt Tino Zottola, VE2GCE, Aug 17, 2020 Operation QRP station can be implemented in one of three ways: 1. Regular transceiver with power dialed down to 1 to 10 watts 2. QRP transmitter + conventional receiver 3. QRP specific transceiver(*) *Many QRP specific transceivers use simple DCO receivers (i.e. less sensitivity than superhet). -

NAQCC Newsletter

NORTH AMERICAN QRP CW CLUB, INC. NAQCC NEWS ISSUE 267 • SEPTEMBER 2020 KEY CLICKS • NEW PAYPAL ADDRESS FOR DONATIONS NAQCC Treasurer Jerry K4KBL says we have a new PayPal account. Please send your donations via PayPal to: • GQRP CONVENTION 2020 — SEPTEMBER 5TH AND 6TH Our friends across the pond are doing a QRP convention via Zoom this weekend. Over 500 participants have already signed up and there's a great lineup of speakers (starting with Hans Summers) and topics. The morning sessions will be awfully early for most of us, but you'll have a chance to play them back at your leisure. http:// www.gqrp.com/convention.htm • NEW ARRL CEO IS AN NAQCC MEMBER Our very own member #6781 David NA2AA was just elected CEO of the ARRL! “Primarily a CW operator, Minster collects unique and vintage bugs and keys.” Congratulations David! Details on page 9. • LOTS OF FIRST-TIMERS IN THE AUGUST SPRINT! Welcome: AC2RL K4VLP K6GPB KG5OWB KJ4YM N0ZIB NZEIM N3OS W4KAC W7CBR & W9SAU. • KILOMETERS-PER-WATT CONTEST GIVES QRP OPS THE ADVANTAGE A new contest next month has a scoring system that rewards minimal power. Multipliers for cw and portable operations. Details on page 21. • IN THIS ISSUE A fun letter challenge you’ve ‘herd’ about, some handy tips, John KE4D tells his radio story, the Prez Sez he has lots of great news, a feature that can be beat, member polls, Sprints, awards, nets, and more. • YOUR STORIES NEEDED Send your article, project, or ham radio biography to Paul KD2MX 2 THE PREZ SEZ.. -

Mfj-971 Qrp Portable Antenna Tuner

MFJ-971 QRP PORTABLE ANTENNA TUNER GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The MFJ-971 is a compact 200-Watt portable tuner compatibly packaged with. MFJ QRP transceivers. The MFJ-971 is also a perfect mate for any of today's ultra-compact SSB radios. It provides a convenient cross-needle type SWR/Wattmeter and features a special user-selectable 6-Watt range for QRP operation. The T-match tuner covers 1.8-30 MHz and tunes almost any coax, wire, or balanced-feed type antenna (a 4:1 toroid balun is built in for balanced line). READING THE CROSS NEEDLE SWR INDICATOR: The MFJ-971 uses a cross- needle style meter to display FORWARD power, REFLECTED power, and SWR simultaneously. To read Forward Power, observe the FORWARD meter scale. To read Reflected Power, observe the REFLECTED meter scale. To read SWR, observe where the two needles cross. The corresponding red curve on the meter face displays your SWR reading. No "zero" or "sensitivity" adjustment is required with cross-needle SWR displays. POWER LEVELS: The FORWARD scale is calibrated from 0-300 Watts and the REFLECTED scale from 0-60 Watts. In the high-power range, read both scales directly (x 1). In the 30 Watt range, move the decimal point one place to the left (x 0.1). For QRP sensitivity (6-Watts FORWARD, 1.2-Watts REVERSE), you must perform a simple conversion to obtain actual power. You can convert in your head by moving the decimal point two places to the left and doubling the reading (ie. 300 W = 3.00 x 2 = 6 W). -

Elmer's Night

1 Flathead Valley Amateur Radio Club “Elmer’s Night ” WHAT CAN I DO NOW THAT I HAVE MY AMATEUR RADIO LICENSE? Find a Club: Absolutely the best way to become active is to join a club. At a club you will find hams involved in various Amateur Radio activities. Each club has it’s own flavor and interests. Folks tend to join a club whose members share similar interests. Check out the clubs in your area and find one that is involved with activities that interest you. All clubs welcome guests so visit them and find which one matches your interest, then GET INVOLVED! You can’t learn to swim until you get your feet wet. Here’s a list of local clubs – (in alphabetical order). Volunteer to help with club activities and you will soon find you have some great new friends. HAM Clubs Kalispell , MT: Flathead Valley Amateur Radio Club - http://www.fvarc.org/ (Local Nets/meetings/Events) Billings, MT: Yellowstone Radio Club -www.k7efa.net/ Bozeman, MT: Gallatin Ham Radio Club -gallatinhamradio.com/ Eureka, MT: Tobacco Valley Amateur Radio Club - tvarc.org/ Great Falls, MT: Great Falls Area Amateur Radio Club - www.w7eca.org/ Great Falls, MT: Electric City Amateur Radio Club - w7ecr.org/ Helena MT: Capitol City Amateur Radio Club - ccarc.org/ Joliet, MT: Beartooth Amatuer Radio Club - wb7ris.tripod.com/index.html Missoula, MT: Hellgate ARC - www.w7px.org/ Hamilton, MT: Bitterroot Amateur Radio Club - w7ftx.tripod.com/ Cranbrook BC: East Kootenay Amateur Radio Club - www.qsl.net/ekarc/ 2 ARRL – National Association for Amateur Radio : Founded in 1914, the ARRL (Amateur Radio Relay League) is the National Association for Amateur Radio. -

Owner's Manual

ELECRAFT KX2 POCKET -SIZED, 80-10 M SSB/CW/D ATA TRANSCEIVER OWNER ’S MANUAL Rev. A7, Dec 18, 2017 © 2017, Elecraft, Inc. All Rights Reserved Contents AM Mode 22 Introduction 4 Advanced Operating Features 23 Key to Symbols and Text Styles 4 Special VFO B Displays 23 Frequency Memories 24 Installation 5 Scanning 24 Operating Position 5 Audio Effects 25 Power Supply 5 Dual Watch 25 Internal Battery 6 Programmable Function Switch (PFn) 25 Utility Mounting Points (Bottom Cover) 7 Receive Audio Equalization (RX EQ) 26 CW Key/Keyer Paddle 8 Transmit Audio Equalization (TX EQ) 26 Headphones and Speakers 8 SSB/CW VFO Offset 26 Internal Microphone 8 Data Modes 27 External Microphone 8 Text Decode And Display 29 Computer/Amp Keying (ACC) 9 Split Operation 29 Auxiliary Outputs (AUX) 9 Digital Voice Recorder (DVR) 30 Program/Test (PGM) 9 Transmit Noise Gate 30 Antennas 10 Cross-Mode Operation 30 Control Panel Reference 12 Custom Power-On Banner 30 Display (LCD) 13 Logging (CW/Data Modes) 31 Transverter Bands 31 Basic Operation 14 Getting Started 14 Options and Accessories 32 Band Selection 15 Firmware Upgrades 33 Mode Selection 15 VFO A and B 16 Remote Control of the KX2 34 Incremental Tuning (RIT and XIT) 16 Configuration 35 Special VFO B Displays 16 Option Module Enables 35 Receive Settings 17 Menu Settings 35 Transmit Settings 19 SSB Mode 20 Calibration 37 CW Mode 21 Reference Frequency 37 2 Receive Opposite Sideband 38 Transmit Bias 38 Transmit Gain 38 Transmit Carrier 39 Transmit Opposite Sideband 39 Menu Functions 40 Troubleshooting 53 Parameter Initialization (EEINIT) 57 Error Messages (ERR nnn) 58 Scrolling Alert Messages 61 Theory Of Operation 62 Glossary of Selected Terms 65 Specifications 67 Customer Service and Support 69 Index 71 3 Introduction The Elecraft KX2 is a pocket-sized, 80-10 m, SSB/CW/data transceiver designed specifically for portable, mobile, and hand-held operation. -

In This Issue

Volume 18, Number 10 October, 2009 The Greensboro Amateur Radio Association Providing Amateur Radio news for the Triad Brian Wilson, KJ4LKY, Editor www.w4gso.org [email protected] transmitting so it’s a natural for Building The Elecraft K1 battery power operation. by Will Ravenell, AI4VE chose the four band option making it The kit consists of three boards, I’ve been getting interested in a K1-4. The bands the Filter Board, QRP operation and have been eyeing included are 40m, the Front Panel the Elecraft kits. After Rob Wittner, 30m, 20m, and Board, and the WG5Q, gave his presentation on either 17m or R F B o a r d . building the K2 at the August GARA 15m (parts for C o n n e c t i o n s meeting I decided to take the plunge. both are included b e t w e e n t h e I’ve built small kits before but the and the choice boards are made K2 looked like more than I wanted is made during w i t h i n - l i n e to tackle right now from both a cost construction). In plugs and there and effort point of view so I ordered addition to the fourth band selection is virtually no point to point wiring. the K1. This little 0.1 to 7 watt CW- there is a choice to be made for band Commands are passed between the only QRP rig comes with either a coverage. By changing a capacitor boards under the control of a PIC two or four band filter board and I and a crystal filter you can select processor on the Front Panel Board. -

June, 2021 Volume 73, Issue 10

June, 2021 Volume 73, Issue 10 Inside This Issue Monthly Program 1 Boardz Buzz 2 Calendar of Events 2 Hamfest 3 Education 4 Public Service Report 5 Can You Help? 6 Radio Elegance 7 Professor’s Pic(k)s 8 My POTA Antenna Setup 9 Tune Up a Stone 10 An Introduction to the Amateur Radio Emergency GIL 10 RAG Formatting 10 Data Network (AREDN) RAGS of the Past 11 Brian O’Connor, KA2CGB, RaRa Vice President VE Team 13 Elmers 13 Please join us for our monthly meeting on Wednesday, 2 June, at 7:00PM ET. RaRa Calendar 14 News From Area Clubs 15 This month's presentation is by Mike Moore, KC2NM. Amateur’s Code 17 HAM Equipment Sale 18 The AREDN is a high speed data network built with Amateur Radio Operators and RaRa Officers 19 Emergency Communications Infrastructure in mind. It has its beginnings in the Ham- Area Club Contacts 20 net mesh network and it uses off the shelf commercial hardware with AREDN devel- oped software operating in ham frequencies. The presentation will include: • The AREDN coverage map • How AREDN is used • What equipment is available • How to download and configure the software • Field demonstration of an AREDN link • Where to go for more information KC2NM was licensed in 1967 as WN8ZPY in southern Ohio. He moved to Rochester in 1976 with a BSEE degree at the University of Cincinnati, and earned an MSEE from RIT. His career focused on software development for assembly and test equipment. Mike retired from Excelis (now Harris) in 2014 His ham radio interests include APRS, Allstar, DSTAR, and DMR. -

February 2021 Longpath

February, 2021 Volume 45, Issue 2 The LongPath A North Alabama DX Club Publication Contents From the President ▪ From the President I saw the February issue of the Long Path com- uting articles, you should think about that one. ing from some distance. I’ve been trying to pack ▪ February Program Another question that got a compelling re- more articles into the newsletter since the plague sponse was the length of the presentations. ▪ Relief for the Weary struck last year. With a small club like ours, 18- Many of you thought the presentation length DXer page issues can’t continue for very long. I was on Zoom was too long. I don’t know how to put afraid of running out of gas, so I scheduled a a hard time length on the presentations, but ▪ Winter Field Day directors’ meeting and sent out a survey a few understand that Zoom does have its limita- ▪ Why I Bought... weeks ago. I was trying to be aggressive, so I tions. You can’t see data very well, and you sent the surveys to almost 90 people. I thank can’t interact with the speaker nearly as well. ▪ Ionospherica those who did respond, and I’ll try to do what you I’ll see what I can do here. I’m also hearing asked. that Zoom is the enabler for members that live ▪ DX Contests far away, and have been asked if we could In last month’s Long Path, I mentioned that I continue to use Zoom after the plague goes ▪ Using Natural was looking for articles regarding your station Resources away. -

Radio Amateur News & Views the Official Journal of the Radio Amateurs of Northern Vermont

Radio Amateur News & Views The Official Journal of the Radio Amateurs of Northern Vermont FEBRUARY 2001 10 Great Years of RANV Vol. 11 No. 2 BORDER PATROL IN THIS ISSUE... COMMUNICATIONS The February 13th RANV Meeting Milton Hamfest 2001 Contest Corner We have a real treat in store for you at the February meeting. Our guest will be Al Willett N1DRO, who works for the United States Border Patrol. He will Ham Classes be speaking about some of the communications and electronics they use to RANV in QST monitor the International border. Joining him will be Mark Pynduss KB1EWA who will talk about the detection sensors they use and Ross McCart KB6GCS CTE Open House who will relate some war stories. Some of the stuff they work with is a linked repeater system with 15 repeaters, remote controlled cameras and micro- Microwave Record wave relays. They also plan to bring some of the goodies for all to see. It should be a really informative evening! Welcome to RANV Don’t forget, the pre-meeting activities start at Zach’s at 6pm. The meeting will start at 7pm and will be held at the O’Brien Civic Center, 113 Patchen Prez Sez Road, South Burlington. See you there! MILTON HAMFEST 2001 The Northern Vermont Winter Hamfest basements, and you have a lot of stuff to look at. Now, The ARRL Vermont State Convention I’ve heard some of you say that you needn’t attend a The Milton Hamfest or, just plain, Miltuhn hamfest since you can buy anything you want on E-bay. -

QRP Transceiver Kits: Six Reports from the Field

By Michael Tracy, KC1SX QRP Transceiver Kits: Six Reports from the Field ith the explosive growth in low QRP rigs to our rigorous “Product Review” For me, the EMTECH step-by-step power (QRP) hamming, report- scrutiny, but I think you’ll enjoy these “build, then test” process was especially W ing on the current state of the grassroots reviews. In many ways, they are helpful. The instructions are not as de- transceiver art is akin to shooting at a rap- every bit as valuable and informative as tailed as the old Heathkit manuals, but idly moving target. We have reviewed full-fledged QST “Product Reviews.” they cover the necessary steps very well. QRP transceiver kits in QST before, but In addition, the builder assembles a sec- this time we were looking for a totally EMTECH NW80/20 tion of the transceiver, then tests that sec- different approach. Rather than follow the By Bob Kellogg, AE4IC tion. So, as more and more components traditional path of buying a QRP kit and [email protected] were added to the board, I wasn’t worry- running it through the usual “Product Re- I own a complete set of EMTECH ing that I’d made some mistake that would view” gauntlet, we decided to go into the NW80/20 transceivers for 80, 40, 30 and be difficult to find later. This “build a sec- field and contact hams who had recently 20 meters—all built from kits. They have tion and test” process also helped me un- built several of the most popular kits.