Smashing the Broken Mirror: the Battle of the Forms, UCC 2-207, and Louisiana's Improvements, 53 La

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offer and Acceptance

ROLL FOLD... DOUBLE CHECK ADJUSTMENTS FOR ROLL FOLD... 1/16" creep. MAKE ADJUSTMENTS FOR DOT GAIN. diligence period expires, the earnest money should “contingencies” must be performed by the dates are a number of exceptions to this requirement. timeshare in North Carolina from a seller classified by these transactions may be riskier than a conventional be refunded to you. If you terminate after the due specified in the contract or very soon thereafter, Consequently, for application of this law to a particular law as a developer of a timeshare project, you have five purchase, you should consult your attorney before into diligence period, the earnest money is usually depending upon whether the contract states that situation, you should consult your attorney. days to cancel your purchase contract which you can do entering such agreements. forfeited to the seller unless the seller is unable “time is of the essence.” If time is of the essence, and • Lead Paint Disclosure. If you are by mail. If you are a resident of another state, you may • Lease-Purchase. In lease-purchase Questions and Answers on: or unwilling to satisfy the terms of the contract. If you or the seller fail to perform by the stated deadline, purchasing a residential building constructed before also have additional rescission rights under the laws of transactions, you occupy property as a tenant but agree there is any dispute between you and the seller the other party may terminate the contract. If the 1978, federal law requires sellers and their brokers to your home state. The developer must hold all funds to purchase it at a future date. -

Contracts Course

Contracts A Contract A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties with mutual obligations. The remedy at law for breach of contract is "damages" or monetary compensation. In equity, the remedy can be specific performance of the contract or an injunction. Both remedies award the damaged party the "benefit of the bargain" or expectation damages, which are greater than mere reliance damages, as in promissory estoppels. Origin and Scope Contract law is based on the principle expressed in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda, which is usually translated "agreements to be kept" but more literally means, "pacts must be kept". Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations, along with tort, unjust enrichment, and restitution. As a means of economic ordering, contract relies on the notion of consensual exchange and has been extensively discussed in broader economic, sociological, and anthropological terms. In American English, the term extends beyond the legal meaning to encompass a broader category of agreements. Such jurisdictions usually retain a high degree of freedom of contract, with parties largely at liberty to set their own terms. This is in contrast to the civil law, which typically applies certain overarching principles to disputes arising out of contract, as in the French Civil Code. However, contract is a form of economic ordering common throughout the world, and different rules apply in jurisdictions applying civil law (derived from Roman law principles), Islamic law, socialist legal systems, and customary or local law. 2014 All Star Training, Inc. -

What Is Invitation to Treat?

Cyber Law: © Dr. Qais Faryadi (F.S.T) www.dr-qais.com WHAT IS INVITATION TO TREAT? Invitation to treat or simply speaking information to bargain means a person inviting others to make an offer in order to create a binding contract. An example of invitation to treat is found in window shop displays and product advertisement. Invitation to treat comes from the Latin phrase invitatio ad offerendum and it means inviting an offer. In another words it is a special expression showing a person’s willingness to negotiate. When a shopkeeper makes an invitation to treat may not accept any offer on his goods as soon as it is accepted by the person who makes an offer. There is a difference between an offer and invitation to treat. When A accepts an offer from B a contract is complete. When B accepts an advertisement in a shop window, he is actually making an offer. It is up to the advertiser to accept or to reject the offer. The issue of invitation to treat was discussed in the case of Fisher v Bell 1 by the English Court of Appeal: “It is perfectly clear that according to the ordinary law of contract the display of an article with a price on it in a shop window is merely an invitation to treat. It is in no sense an offer for sale the acceptance of which constitutes a contract.” As such when a person displays a good on his shop or advertises something in his shop window merely bargaining an offer on it. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

Beyond Unconscionability: the Case for Using "Knowing Assent" As the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-For Terms in Standard Form Contracts

Beyond Unconscionability: The Case for Using "Knowing Assent" as the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-for Terms in Standard Form Contracts Edith R. Warkentinet I. INTRODUCTION People who sign standard form contracts' rarely read them.2 Coun- sel for one party (or one industry) generally prepare standard form con- tracts for repetitive use in consecutive transactions.3 The party who has t Professor of Law, Western State University College of Law, Fullerton, California. The author thanks Western State for its generous research support, Western State colleague Professor Phil Merkel for his willingness to read this on two different occasions and his terrifically helpful com- ments, Whittier Law School Professor Patricia Leary for her insightful comments, and Professor Andrea Funk for help with early drafts. 1. Friedrich Kessler, in a pioneering work on contracts of adhesion, described the origins of standard form contracts: "The development of large scale enterprise with its mass production and mass distribution made a new type of contract inevitable-the standardized mass contract. A stan- dardized contract, once its contents have been formulated by a business firm, is used in every bar- gain dealing with the same product or service .... " Friedrich Kessler, Contracts of Adhesion- Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract, 43 COLUM. L. REV. 628, 631-32 (1943). 2. Professor Woodward offers an excellent explanation: Real assent to any given term in a form contract, including a merger clause, depends on how "rational" it is for the non-drafter (consumer and non-consumer alike) to attempt to understand what is in the form. This, in turn, is primarily a function of two observable facts: (1) the complexity and obscurity of the term in question and (2) the size of the un- derlying transaction. -

Is an Advertisement an Offer? Why It Is, and Why It Matters Jay M

Hastings Law Journal Volume 58 | Issue 1 Article 2 1-2006 Is an Advertisement an Offer? Why It Is, and Why It Matters Jay M. Feinman Stephen R. Brill Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jay M. Feinman and Stephen R. Brill, Is an Advertisement an Offer? Why It Is, and Why It Matters, 58 Hastings L.J. 61 (2006). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol58/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is an Advertisement an Offer? Why It Is, and Why It Matters JAY M. FEINMAN* AND STEPHEN R. BRILL** INTRODUCTION Courts and scholars uniformly recite the contract law rule familiar to all first-year students: An advertisement is not an offer. The courts and scholars are wrong. An advertisement is an offer. This Article explains why the purported rule is not the law, why the actual rule is that an advertisement is an offer, why that rule is correct, and what it tells us about contract law in particular and legal doctrine in general. I. THE TRADITIONAL RULE: AN ADVERTISEMENT Is NOT AN OFFER It is Hornbook law' that an advertisement is not an offer. Williston self-assuredly declared the rule to be an application of the dividing line between preliminary negotiations and offers: Frequently, negotiations for a contract are begun between parties by general expressions of willingness to enter into a bargain upon stated terms and yet the natural construction of the words and conduct of the parties is rather that they are inviting offers, or suggesting the terms of a possible future bargain than making positive offers. -

IN the COURT of APPEALS of IOWA No. 17-0482 Filed April 18

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF IOWA No. 17-0482 Filed April 18, 2018 JM 48, LLC, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. HEARTLAND CO-OP, Defendant-Appellant. ________________________________________________________________ Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Polk County, Jeffrey D. Farrell, Judge. Heartland Co-op appeals a district court ruling denying its motion to compel arbitration. AFFIRMED. John F. Lorentzen of Nyemaster Goode, P.C., Des Moines, for appellant. Gina C. Badding of Neu, Minnich, Comito, Halbur, Neu & Badding, P.C., Carroll, for appellee. Heard by Vogel, P.J., and Potterfield and Mullins, JJ. 2 MULLINS, Judge. Heartland Co-op (Heartland) appeals a district court ruling denying its motion to compel arbitration. Heartland contends the parties entered into an arbitration agreement that is enforceable under the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) as well as the Iowa Arbitration Act (IAA) and, therefore, the district court erred in denying its motion to compel arbitration. Heartland alternatively argues an arbitration agreement should be enforced through the doctrine of promissory estoppel.1 I. Background Facts and Proceedings The following facts are generally undisputed. In May 2010, Gerald Murphy, on behalf of JM 48, LLC (JM), signed a contract authorization form with Heartland. The authorization form provided: I the customer grant the following individuals authorization to enter into grain contracts on behalf of the account name and number stated above, including credit sale contracts and warehouse receipts. Contracting of Grain: I represent to Heartland on behalf of the Customer that: (1) we routinely sell grain to elevator; (2) we have the particular skills and knowledge of grain trading practices that enable us to understand the terms of grain sale contracts enter into; (3) we are a merchant with respect to the sale of grain; and (4) each of the individuals names above is authorized to enter into grain contracts with Heartland on our behalf. -

Smashing the Broken Mirror: the Battle of the Forms

Law Review SMASHING THE BROKEN MIRROR: THE BATTLE OF THE FORMS, UCC 2-207, AND LOUISIANA'S IMPROVEMENTS Smashing &heBroken ,Mirror: The Battle of the Forms, UGC 2-207, and Louisirasrra% Improvements TABLE OF CONTENTS I. introduction.. ......................................................... 11. The Mirror Image Rule and the Last Shot Principle ... 111. Formation of Contracts in Louisiana-Presenm1 and Future ........................ .. ....................................... IT. UCC Section 2-28'? Problems and Civil Code Solutions ............................................................. A. Where Acceptance is ""Expressly Conditional". ..... I. The Meaning of ""Expressly Conditional" ...... 2. Article 260 l -Omission of '"Expresslyq'-Ap- parent Disadvantages ................................... 3. Article 2681 -Omission of ""Expressly"- Advantages ............................ .. ............. B. Expression of Acceptance ............................... ... C. Additional and Different Terms as Proposals for Modification .................................................... D. Additional Terms that ""Materially Alter9' the Contract ....................... ................................. 1. ""Different Terms" and Acceptance by Silence 2. ""Materially Alter" ...*............... ............... 3. Is it the Offer, or is it the Contract, that is . Materially Altered"? ................................ E. Where the Offer Limits Acceptance to the Terans of the Offer .................................................... I. Ambiguity of Offer-Reskrictioras -

Clearing the Air After the Battle: Reconciling Fairness and Efficiency in Aormal F Approach to U.C.C

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 33 Issue 3 combined issue 3 & 4 Article 3 1983 Clearing the Air after the Battle: Reconciling Fairness and Efficiency in aormal F Approach to U.C.C. Section 2-207 Gregory M. Travalio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gregory M. Travalio, Clearing the Air after the Battle: Reconciling Fairness and Efficiency in aormal F Approach to U.C.C. Section 2-207, 33 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 327 (1983) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol33/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 33 1983 Numbers 3 & 4 Clearing the Air After the Battle: Reconciling Fairness and Efficiency in a Formal Approach to U.C.C. Section 2-207 Gregory M. Travalio* Section 2-207 of the Uniform Commercial Code addresses the "Battle of the Forms." In a typical commercialtransaction, a sellermay respondto a buyer's offer by proposingadditional or diferent terns and expressly conditioningits acceptance on the buyer's assent to these terms. f the partiessubsequently perform, despite the failure ofthe forms to match, a question arisesas to the terms of the resulting con- tract. ThisArticle examines both scholarly commentary and casesproposingalterna- tive methods of applying section 2-207 to this scenario. -

Obligations - Offer and Acceptance William H

Louisiana Law Review Volume 17 | Number 1 Survey of 1956 Louisiana Legislation December 1956 Obligations - Offer and Acceptance William H. Cook Jr. Repository Citation William H. Cook Jr., Obligations - Offer and Acceptance, 17 La. L. Rev. (1956) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol17/iss1/34 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 240 LOUISIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol. XVII fendant's argument that the provision is directory.27 The only difficulty with the opinion is that the court failed to indicate upon what evidence it based its decision. Although the "three different days" requirement is one of those which need not be proved by a Journal entry, in the instant case the Journal did show that the act had been read on only two days in the Senate. 28 Since the Journal is conclusive proof of the legislative proceed- ings,29 the act is invalid, and the court correctly ignored de- fendant's argument that the presumption of compliance should control. The failure of the court to indicate that the fatal in- firmity was proved by a Journal entry is important because if the Journal had not shown a violation, the court would have had to presume conclusively that the bill had been read on three days, and uphold the act.8 0 Edwin L. Blewer, Jr. -

Default Rules in Sales and the Myth of Contracting out James J

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2002 Default Rules in Sales and the Myth of Contracting Out James J. White University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/381 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation White, James J. "Default Rules in Sales and the Myth of Contracting Out." Loyola L. Rev. 48, no. 1 (2002): 53-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEFAULT RULES IN SALES AND THE MYTH OF CONTRACTING OUT James J. White* I. INTRODUCTION In his celebrated article The Problem of Social Cost,1 Ronald Coase argued that rules of law alterable by agreement were not inherently inefficient because parties could and would negotiate to an efficient result. Coase explicitly qualified his principle with the corollary that the costs of negotiating might keep parties from reaching efficient outcomes. 2 Where this is so, the existing law that governs the transaction - now sometimes called the "default rule" - prevails despite its inefficiencies. In the modern sale of goods, Coase's corollary has overtaken the principle. Few contracts for the sale of goods are fully negotiated either in person or by electronic or other remote communication. -

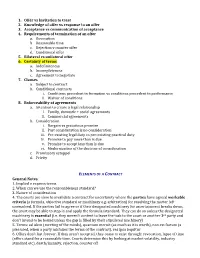

1. Offer Vs Invitation to Treat 2. Knowledge of Offer Vs Response to an Offer 3

1. Offer vs Invitation to treat 2. Knowledge of offer vs response to an offer 3. Acceptance vs communication of acceptance 4. Requirements of termination of an offer a. Revocation b. Reasonable time c. Rejection v counter offer d. Conditional offer 5. Bilateral vs unilateral offer 6. Certainty of terms a. Indefiniteness b. Incompleteness c. Agreement to negotiate 7. Clauses a. Subject to contract b. Conditional contracts i. Conditions precedent to formation vs conditions precedent to performance ii. Waiver of conditions 8. Enforceability of agreements a. Intention to create a legal relationship i. Family, domestic + social agreements ii. Commercial agreements b. Consideration i. Bargain vs gratuitous promise ii. Past consideration is no consideration iii. Pre-existing legal duty vs pre-existing practical duty iv. Promise to pay more than is due v. Promise to accept less than is due vi. Modernization of the doctrine of consideration c. Promissory estoppel d. Privity ELEMENTS OF A CONTRACT General Notes 1. Implied v express terms 2. When can we use the reasonableness standard? 3. Nature of consideration 4. The courts are slow to invalidate a contract for uncertainty where the parties have agreed workable criteria (a formula, objective standard or machinery e.g. arbitration) for resolving the matter left unresolved. If the parties fail to agree or if their designated machinery for ascertainment breaks down, the court may be able to step in and apply the formula/standard. They can do so unless the designated machinery is essential (i.e. they weren’t content to leave the task to the court or another 3rd party and don’t intend to be bound unless the gap is filled by their stipulated machinery) 5.