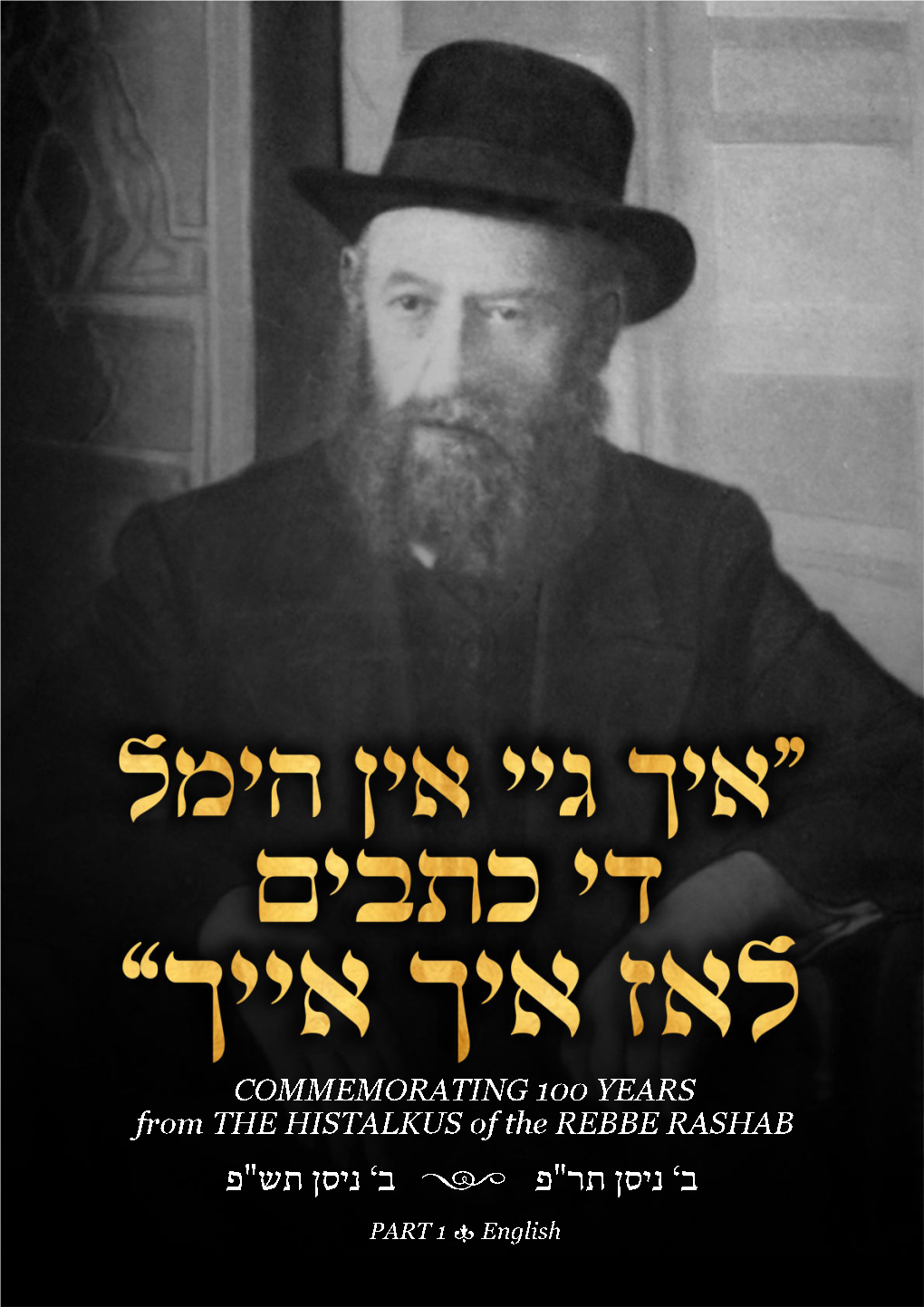

Kovetz Beis Nissan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESTUDIOS DEL TANAJ 54 Falsos Mesías Judíos

ESTUDIOS DEL TANAJ 54 Falsos Mesías Judíos Por: Eliyahu BaYona Director Shalom Haverim Org New York Estudios del Tanaj – Estudios del Tanaj 54 Yeshayahu 9 • 1. El pueblo que andaba en tinieblas, vio una luz grande. Sobre los que habitan en la tierra de sombras de muerte resplandeció una brillante luz. • 2. Multiplicaste la alegría, has hecho grande el júbilo, y se gozan ante ti, como se gozan los que recogen la mies, como se alegran los que reparten la presa. • 3. Rompiste el yugo que pesaba sobre ellos, el dogal que oprimía su cuello, la vara del exactor como en el día de Madián, • 4. y han sido echados al fuego y devorados por las llamas las botas jactanciosas del guerrero y el manto manchado en sangre. • 5 Pues nos ha nacido un hijo, un hijo que nos ha sido dado, y la autoridad está sobre su hombro, y el maravilloso consejero, el poderoso Dios, el Padre eterno, llamó su nombre, "el príncipe de la paz". • 6 En señal de abundante autoridad y de paz sin límite sobre el trono y el reino de David, para que se establezca firmemente en justicia y en equidad ahora y siempre. El celo del Señor de los ejércitos hará que esto suceda.. Estudios del Tanaj 54 Yeshayahu 9 • 6 En señal de abundante autoridad y de paz sin límite sobre el trono y el reino de David, para que se establezca firmemente en justicia y en equidad ahora y siempre. El celo del Señor de los ejércitos hará que esto suceda.. • Lemarbé hamisrá uleshalom en kes al kisé David ve’al mamlakto lehakin otá ulesa’ada bemishpat ubitzdaká me’atá ve’ad olam kinat Adonai tzevaot ta’aseh zot. -

Yud-Tes Kislev 5775

גליון א' )קל“ח( י‘‘ט כסלו -MELBOURNE- ISSUE 26 יוצא לאור ע“י תלמידים השלוחים ישיבה גדולה מלבורן Yud Tes Kislev שנת חמשת אלפים שבע מאות שבעים וארבעה וחמש לבריאה 5775 ”ממזרח שמש עד מבואו מהלל שם ה‘“ KOVETZ - Melbourne - 26 YUD TES KISLEV, 5775 2 HEOROS HATMIMIM V’ANASH - MELBOURNE PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENTS OF THE RABBINICAL COLLEGE OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND ● A project of The Talmidim Hashluchim Hatomim Shmuel Shlomo Lezak Hatomim Arie Leib Gorowitz 67 Alexandra st. East St. Kilda Victoria 3183 Australia [email protected] YUD TES KISLEV - 5774 3 מוקדש לכ"ק אדמו"ר נשיא דורנו יה"ר שיראה הרבה נחת מבניו – התמימים בפרט משלוחיו, חסידיו, וכלל ישראל בכלל ומזכה להגאולה האמיתית והשלימה תיכף ומיד ממש * מוקדש ע"י ולזכות התלמידים השלוחים מנחם מענדל שי' גורארי' מנחם מענדל שי' שפיצער מנחם מענדל שי' שוחאט מנחם מענדל שי' ראסקין מרדכי שי' רובין ניסן אייזק שי' הלל מנחם מענדל שי' אקוניוו יהודה ארי' ליב הלוי שי גורביץ מנחם מענדל שי' ווינבוים מתתיהו שי' חאריטאן שמואל שלמה שי' ליזאק עובדיה גרשון דוד שי' ראגאלסקי 4 HEOROS HATMIMIM V’ANASH - MELBOURNE לזכות התלמידים השלוחים במעלבורן להצלחה רבה בשליחותם ובפרט בשליחותם במחנה קיץ גן ישראל שיזכו להחדיר בלב ילדי תשב''ר יראת שמים ודרכי החסידות כרצון ולנח"ר כ"ק אדמו"ר נשיא דורנו! נדפס ע"י ולזכות יו"ר צא"ח במעלבורן ר' משה וזוגתו שיחיו קאהן לזכות החתן הרה"ת ישראל שי' בארבער עם ב"ג הכלה מרת רחלשתחי' כהן לרגל בואם בקשרי השידוכין ויה"ר שימלא השי"ת כל משאלות לבם בכל המצטרך בגשמיות וברוחניות, ויבנו בנין עדי עד ולנח"ר כ"ק אדמו"ר נשיא דורנו! * נדפס ע"י ולזכות הורי הכלה – ראש ישיבתינו הרה"ג הרה''ח בנימין גבריאל הכהן וזוגתו שיחיו כהן YUD TES KISLEV - 5774 5 לעילוי נשמת האשה החשובה מרת רחל גיטל חיה ע"ה בת ר' אברהם אבא הלוי ע"ה נפטרה ביום י"ב כסלו ה'תש"ס ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. -

The Rebbe's Sicha to the Shluchim Page 2 Chabad Of

1 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 כאן צוה ה’ את הברכה CommunityNewspaper פרשת חיי שרה | כג' חשון , תשס”ט | בס”ד WEEKLY VOL. II | NO 4 NOVEMBER 21, 2008 | CHESHVAN 23, 5769 WELCOME SHLUCHIM! Page 3 HoraV HachossiD CHABAD OF CHEVRON REB AharoN ZAKON pAGE 12 THE REBBE'S SICHA TO THE SHLUCHIM PAGE 2 Beis Din of Crown Heights 390A Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, NY Tel- 718~604~8000 Fax: 718~771~6000 Rabbi A. Osdoba: ❖ Monday to Thursday 10:30AM - 11:30AM at 390A Kingston Ave. ☎Tel. 718-604-8000 ext.37 or 718-604-0770 Sunday-Thursday 9:30 PM-11:00PM ~Friday 2:30PM-4:30 PM ☎Tel. (718) - 771-8737 Rabbi Y. Heller is available daily 10:30 to 11:30am ~ 2:00pm to 3:00pm at 788 Eastern Parkway # 210 718~604~8827 ❖ & after 8:00pm 718~756~4632 Rabbi Y. Schwei, 4:00pm to 9:00pm ❖ 718~604~8000 ext 36 Rabbi Y. Raitport is available by appointment. ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ☎ Rabbi Y. Zirkind: 718~604~8000 ext 39 Erev Shabbos Motzoei Shabbos Rabbi S. Segal: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ❖ Sun ~Thu 5:30pm -9:00pm or ☎718 -360-7110 Rabbi Bluming is available Sunday - Thursday, 3 -4:00pm at 472 Malebone St. ☎ 718 - 778-1679 Rabbi Y. Osdoba ☎718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 10:0am -11:30am ~ Fri 10:am - 1:00 pm or 4:16 5:17 ☎ 718 -604-0770 Gut Shabbos Rabbi S. Chirik: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 5:00pm to 9:00pm 2 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 The Vaad Hakohol REBBE'S STORY “When one tells a story about his Rebbe he connects to the deeds of the Rebbe” (Sichos 1941 pg. -

The-Atvotzkers.Pdf

THE ATVOTZKERS Memento from the wedding of Geulah and Chaim The Lives of Rabbis Kohn Moshe Elya Gerlitzky Rosh Chodesh Shevat, 5781 and Mottel Bryski The 14th of January, 2021 Atvotzkers Cover - B.indd 1 1/6/2021 11:03:19 AM בס"ד THE ATVOTZKERS The Lives of Rabbis Moshe Elya Gerlitzky and Mottel Bryski DOVID ZAKLIKOWSKI The Atvotzkers © 2021 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, without prior permission, in writing. Many of the photos in this book are courtesy and the copyright of Lubavitch Archives. www.LubavitchArchives.com [email protected] Design by Hasidic Archives Studios www.HasidicArchives.com [email protected] Printed in the United States Memento from the wedding of חיים אלעזר וגאולה שיחיו הכהן קאהן Geulah and Chaim Kohn ראש חודש שבט ה’תשפ”א The 14th of January, 2021 Greetings Dear family and friends, Thank you for being a part of oursimchah ! It is customary at Jewish weddings to remember the deceased grandparents of the chassan and kallah. Considering our grandfathers’ shared histories and friendship, it seemed appropriate to record the stories of their lives in honor of our wedding. Chaim’s grandfather, Rabbi Mordechai Meir (“Mottel”) Bryski, was generally a man of few words. When pressed to speak, he pre- ferred to do it through song. Singing played a central role in his life. Be it the songs he grew up with, Chabad nigunim or the nigunim he would sing and compose during his daily prayers. His favorite was the Shir Hageulah, the Song of Redemption (see page 34). -

Perspectives Issue

FOREWORD FOREWORD Are You For Real? R. Alexander Bin-Nun was the general overseer of the network of Oholei Yosef Yitzchak schools in Eretz Yisroel. In his effort to guide the teachers, he prepared a list of what he considered the ten foremost principles of education. During his next yechidus, he presented the list to their Rebbe. “It’s missing the most important principle,” the Rebbe told him, “The first principle inchinuch is that there are no ‘general principles!’” THE theory of catering to individual needs has become very popular in recent years. We talk about each child’s unique strengths, and Truthfully, the need to teach children ““al pi darko,”” according to their way. Still, again and again, we find ourselves setting up systems to regulate however, there’s no children’s conduct – rules, grading, awards and chores. Even loose school settings, which teach with differentiated instruction and grade way to systemize according to individual abilities, often have intricate procedures for using those methods and for regulating overall conduct. Genuine care personal attention, and connection are replaced with “personalized systems.” since any Truthfully, however, there’s no way to systemize personal attention, since any predetermined program isn’t personal. A sequenced program predetermined of conduct or consequence is never responding to the needs of that child at that moment. Only by listening to child and reading their eyes, can we program respond to their exact needs. isn’t personal. Western SOCIETY is distrustful of personal judgment. To secure our airports, for example, we will impose extensive procedures, rather than just call out suspicious individuals, (as our brothers in Eretz Yisroel have successfully done for years). -

Every Jew's Obligation

He’aros and Pilpulim Every Jew’s Obligation CHESHVAN 5779 16 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER מוקדש לחיזוק ההתקשרות לכ"ק אדמו"ר נשיא דורנו נדפס ע"י הרה"ת ר' מרדכי וזוגתו מרת חי' מושקא ומשפחתם שיחיו גראסבוים סטאני ברוק, ניו יארק RASKIN FAMILY ARCHIVES CHESHVAN 5779 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER 17 What’s the point? One of the most enduring characters in Chassidic literature is that of the fantastically egotistical Torah scholar from the early time-period of Chassidus: geonim who imagined themselves greater than Moshe Rabbeinu (and found themselves questioning Hashem’s judgement as a result)1; hermits who could not comprehend why Eliyahu Hanavi would not appear to them2; and Talmudists who sincerely thought of Rashi as an inferior caliber scholar to themselves.3 Their self-worth was measured by their achievements and innovations in Torah-study, ONE OF and as much as they studied, a true appreciation for Elokus and avodas THE MOST Hashem was nonexistent. Perhaps For generations, many Chassidim CRITICAL ENDEAVORS IN THE scorned the notion of focussing on one’s own innovations in Torah, DEVELOPMENT OF ONESELF AS A viewing it as synonymous with leaving Elokus out of the picture, a relic of CHOSSID IS TO FOSTER IN ONESELF these self-absorbed scholars. This attitude is alive and true CHASSIDISHE HANACHOS, A today, in one form or the other. Many view chiddushim as the purview of CHASSIDISHE OUTLOOK ON LIFE. the elite, of those who “know how to learn,” of roshei yeshivos and rabbonim As we grow into adults, we develop a fundamental perspective on life from (and overconfident youngsters). -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held May 2Nd, 2013

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts & autograph Letters including hoLy Land traveL the ColleCtion oF nathan Lewin, esq. K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m ay 2nd, 2013 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 318 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, & AUTOGRAPH LETTERS INCLUDING HOLY L AND TR AVEL THE COllECTION OF NATHAN LEWIN, ESQ. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, May 2nd, 2013 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, April 28th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, April 29th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, April 30th - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, May 1st - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Pisgah” Sale Number Fifty-Eight Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. (Consultant) Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

It's Story and History Machanayim Books

בס"ד MISHNAYOS BAAL PEH PRIZE LIST You may choose one sefer for all your points or a number of sefarim which equal up to your points Please note: Actual prizes may be a little different than the way it looks in the picture HOW TO CHOOSE A SEFER FOR YOUR PRIZE FOR MISHNAYOS BAAL PEH You may choose one sefer for all your points, or a number of Sefarim which equal up to your points. If you would like a different Sefer, please reach out to Rabbi Heidingsfeld. Please note - a blue is worth a value of 20c, yellow - $1, red - $5, gold - $25, crown - $125. Prices are calculated as the cost of Seforim locally in Los Angeles. Please look at the points list for how many points you have and then choose your seforim and fill out this form https://forms.gle/zLhcYAanifVsLCiL9 up to three yellows - Mincha Maariv 3 yellows - Roshei Perakim Mitoldos Arbaah Mechabrim 4 Yellows - Kuntres Inyanah Shel Toras Hachassidus 1Red - pocketsize Tehillim 1 Red 1 Yellow - pocketsize Hayom Yom 1 red 3 yellows - pocketsize siddur 1 red 4 Yellows - Divrei torah for children Vol 1 1 red 4 Yellows - Divrei torah for children Vol 2 Two Reds The Tanya – It’s Story and History Machanayim Books- Hardcover- Assorted volumes available –EACH Hardcover Pocketsize Siddur with Tehillim Two Reds two yellows Pocketsize set of Nach Pocketsize set of Chumash Pocketsize set of Mishnayos Pocketsize set of Shnayim Mikra Farbreng with Reb Shmuel Munkes Two Reds one yellow The Rebbeim Two Reds two yellows two blues Shaloh Two Reds three yellows בס"ד MISHNAYOS BAAL PEH PRIZE LIST You may -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, Ceremonial obJeCts & GraphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, nov ember 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 61 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, GR APHIC & CEREMONIAL A RT INCLUDING A SINGULAR COLLECTION OF EARLY PRINTED HEBREW BOOK S, BIBLICAL & R AbbINIC M ANUSCRIPTS (PART II) Sold by order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th November, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th November - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 16th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Sempo” Sale Number Sixty Six Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky (Consultant) Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

ELUL 5778 6 a CHASSIDISHER DERHER in Meron, Tzfas and Teveria, for the Rebbe to Accept the Nesius

מוקדש לחיזוק ההתקשרות לנשיאנו כ"ק אדמו"ר לעבן מיט'ן רבי'ן נדפס ע"י הרה"ת ר' אברהם שמואל ומרת חי' צפורה בניהם ובנותיהם מושקא, מנחם מענדל, נעכא, יוסף, שיחיו מאן “We Are His Shluchim!” ELUL 5710 fter the histalkus of the Frierdiker Rebbe on MONDAY, 15 ELUL AYud Shevat 5710, Chassidim worked tirelessly Rabbi Yerachmiel Benjaminson (known as the for the Rebbe to accept the nesius. Although the Zhlobiner Rov) arranged for a minyan of elder Rebbe finally agreed to accept the nesius only a and younger Chassidim to travel together to the year later, throughout the year of aveilus, there Ohel. They read a pan kloli on behalf of all anash, were many developments and stages leading to requesting that the Frierdiker Rebbe instruct the that point. During the month of Elul, the urgency Rebbe to accept the nesius of Lubavitch. by adas haChassidim worldwide intensified and the On the same day, a delegation of elder Chassidim Rebbe filled certain roles unique to a Rebbe.1 in Eretz Yisroel davened at the mekomos hakdoshim ELUL 5778 6 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER in Meron, Tzfas and Teveria, for the Rebbe to accept the nesius. Hatomim Elya Gross was in yechidus together with a bochur that had been drafted to the U.S. Army. The Rebbe inquired if he had already passed the physical exam and then said that the (Frierdiker) Rebbe wrote a letter to all Jewish soldiers serving in the army, explaining that people experience much in life, but everything is temporary. The only thing that is permanent and eternal is Torah and mitzvos. -

Hatomim—Our History, Heritage, and Scholarship

A Light from LUBAVITCH HATOMIM—OUR HISTORY, HERITAGE, AND SCHOLARSHIP In today’s day and age, when the Jewish street is filled with daily and monthly newspapers from all spectrums and parties, filling the minds with new ideas and aspirations, it is essential that the truth—the clear, authentic voice of Torah be sounded in the public sphere. But more importantly, our new periodical serves a purpose especially for us, alumni of Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim of Lubavitch. After the chaos brought on by the most recent war [World War I] as a tumultuous world has been disoriented, our brothers and friends the temimim find themselves scattered about in various countries across the whole world, far away from one- another. Friends who spent their best years basking in Torah and Chassidus in Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim, bound together in love, are now far apart. By Divine decree, one resides in the United States, another in Great Britain, another in Eretz Hakodesh. There is little contact between them and no opportunity to discuss the most important mission we have, to spread Torah and Yiddishkeit. It is this situation that calls for the creation of this medium—a periodical that can serve as a unifying voice; the voice of Torah, nigleh and Chassidus. It will serve as a place for inspiration and instruction about the work we need to do as temimim, strengthening Torah and spreading the teachings of Chassidus. Moreover, it will allow us to hear from all our friends around the world of their wellbeing and about their activities in strengthening Yiddishkeit in their respective places… (Editors’ introduction to the first issue of Hatomim) In preparing this article we were greatly assisted by Rabbi Avraham D. -

Rebbetzin Chave Hecht Working at Her Desk for Camp Emunah, As She Has for the Past 60 Years

Rebbetzin Chave Hecht working at her desk for Camp Emunah, as she has for the past 60 years. 22 n’shei Chabad NEWSLETTER | nsheichabadnewsletter.com Rebbetzin Chave The name Rebbetzin Chave Hecht, zol gezunt zein, is synonymous with Camp HechtEmunah, the first Chabad overnight camp which she and her late husband, the legendary activist, chossid, counselor and educator Rabbi Yaakov Yehuda (J.J.) Hecht, founded in 1953. Rebbetzin Hecht has been running Camp Emu- nah for 60 years without stop. Rebbetzin Hecht was interviewed exclusively for the N’shei Chabad Newsletter by Mrs. Rosa Grossman. hen my husband and I were chosson and kallah, in the year 5705 (1945), it was customary to have yechidus with the Fri- erdiker Rebbe before the chassunah. We were told two or three weeks before our chassunah that the Freirdiker Rebbe was not feeling well. My chosson made a call every day to the Frierdiker Rebbe’s office to inquire about the Rebbe’s Whealth. The answer he got was always the same: “The Rebbe is not feeling well.” On Sunday morning, the day of our chassunah, I got a call from the Frier- diker Rebbe’s office, telling me to come with my parents and grandparents to 770. My chosson also received the same phone call, telling him to come with his parents. Upon arriving at 770, the Frierdiker Rebbe’s secretary put each fam- ily in a separate room. The Frierdiker Rebbe was then told that both families, with the chosson and kallah, were in 770. The Frierdiker Rebbe gave instruc- tions to his secretary to tell both families to come in together with the chosson and the kallah.