IJAH Vol 9 (1), S/No 32, January, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

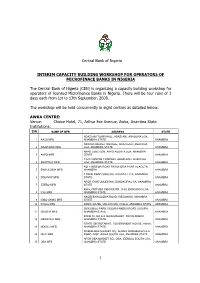

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

A Study of Awka Metropolis Anambra State, Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 7, No. 5; May 2016 Urban Poverty Incidence in Nigeria: A Study of Awka Metropolis Anambra State, Nigeria Mbah, Stella I., Ph.D Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Mgbemena, Gabriel C. Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Ejike, Daniel C. Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Abstract This study examined poverty situation in Awka metropolis of Anambra State, Nigeria, using the P-alpha class of poverty measure. To achieve this objective, a structured questionnaire was administered to 399 heads of households selected from mixed socio-economic backgrounds. The study revealed that 49 percent of the respondents were considered to be poor, with 0.17 poverty gap index and a 0.03 severity of poverty index. However, the indicators were considered to be modest when compared with the national rates. The causes of poverty in Awka metropolis include: lack or inadequate supply of some identified basic necessities of life such as shelter, potable water, and sanitation, basic healthcare services, electricity and educational services. As a result of these inadequacies, there are psychological distress, increase in destitution, child labour, violent crime, and prostitution. It was therefore recommended among others that government should step up public investment in urban infrastructure, provision of credit facilities, involvement of the people in development decision that affects their lives or participatory budgetary process and most especially, good governance at the municipal level with accountability and transparency to stamp out corrupt tendencies which has inhibited past developmental efforts of the government. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Household Water Demand in the Peri-Urban Communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria

Vol. 6(6), pp. 237-243, August, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2013.0385 Journal of Geography and Regional Planning ISSN 2070-1845 © 2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Household water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria E. E. Ezenwaji1*, P.O. Phil-Eze2, V. I. Otti3 and B. M. Eduputa4 1Department of Geography and Meteorology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. 3Civil Engineering Department, Federal Polytechnic, Oko, Nigeria. 4Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Accepted 22 July, 2013 The aim of this paper is to determine relevant factors contributing to the water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka capital city. Towards achieving this aim, questionnaire were developed and served on the households in various communities to collect relevant data on the 13 physical and socio- economic factors we earlier identified as influencing water demand in the area. Water quality was ascertained through microbiological analysis of water samples. The major analytical techniques used were multiple correlations, the result of which was subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression. Result shows that the 13 variables combined to contribute 90.0% of water demand in the area. Furthermore, the low standard error of estimates of 0.029 litres shows that water demand in the communities could be predicted using the 13 variables. Policy and planning measures to improve the water supply situation of the area were suggested. Key words: Capital, communities, factors, peri-urban, water demand. -

CHRISTIANITY of CHRISTIANS: an Exegetical Interpretation of Matt

CHRISTIANITY OF CHRISTIANS: An Exegetical Interpretation of Matt. 5:13-16 And its Challenges to Christians in Nigerian Context. ANTHONY I. EZEOGAMBA Copyright © Anthony I. Ezeogamba Published September 2019 All Rights Reserved: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN: 978 – 978 – 978 – 115 – 7 Printed and Published by FIDES MEDIA LTD. 27 Archbishop A.K. Obiefuna Retreat/Pastoral Centre Road, Nodu Okpuno, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State, Nigeria (+234) 817 020 4414, (+234) 803 879 4472, (+234) 909 320 9690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fidesnigeria.com, www.fidesnigeria.org ii DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to my dearest mother, MADAM JUSTINA NKENYERE EZEOGAMBA in commemoration of what she did in my life and that of my siblings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the handiwork of God in my life who is the author of my being. I am grateful to Most Rev. Dr. S.A. Okafor, late Bishop of Awka diocese who gave me the opportunity to study in Catholic Institute of West Africa (CIWA) where I was armed to write this type of book. I appreciate the fatherly role of Bishop Paulinus C. Ezeokafor, the incumbent Bishop of Awka diocese together with his Auxiliary, Most Rev. Dr. Jonas Benson Okoye. My heartfelt gratitude goes also to Bishop Peter Ebele Okpalaeke for his positive influence in my spiritual life. I am greatly indebted to my chief mentor when I was a student priest in CIWA and even now, Most Rev. -

STRUCTURE PLAN for Awka and SATELLITE TOWNS

AWKA STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State STRUCTURE PLAN FOR AWKA AND SATELLITE TOWNS Anambra State 1 Structure Plan for Awka and Satellite Towns Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2009 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme publications can be obtained from UN-HABITAT Regional and Information Offices or directly from: P.O.Box 30030, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Fax: + (254 20) 762 4266/7 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unhabitat.org HS/1152/09E ISBN: 978-92-1-132118-0 DISCLAIMER The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States. Excerpts from this publication may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. Photo Credits : © UN-HABITAT acknowLEDGEMents Director: Dr Alioune Badiane Principal Editor: Prof. Johnson Bade Falade Co-ordinator: Dr. Don Okpala Principal Authors: Prof. Louis C. Umeh Prof. Samson O. Fadare Dr. Carol Arinze –Umobi Chris Ikenna Udeaja Tpl. (Dr) Francis Onweluzo Design and Layout: Andrew Ondoo 2 FOREWORD t is now widely It is to reverse and stem this development trend acknowledged and to realize the developmental potentials of well- and accepted that planned and managed cities, towns and villages, that citiesI and urban areas my Government approached the United Nations are engines of economic Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) in development and growth. -

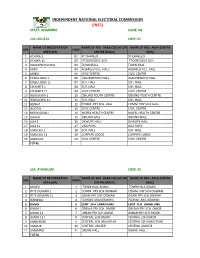

State: Anambra Code: 04

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

Estimation of Aquifer Parameters in Awka and Environs, Anambra State, Nigeria, Using Electrical Resistivity Method

International Journal of Innovative Scientific & Engineering Technologies Research 8(4):1-29, Oct.-Dec., 2020 © SEAHI PUBLICATIONS, 2020 www.seahipaj.org ISSN: 2360-896X Estimation of Aquifer Parameters in Awka and Environs, Anambra State, Nigeria, using Electrical Resistivity Method Onyenweife, G.I1*., Nwozor, K.K1., Onuba, L.N1., Nwike, I.S1 & Egbunike, M.E1. Department of Geology, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Uli, Nigeria *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The indiscriminate drilling and increasing populace and their economic activities have been in collaboration to abstraction of groundwater potential in the study area. Apparently, the above mentioned challenges of Awka and environs have proven the basis to unleash the aquiferous zones and parameters from the analysis of groundwater system for proper knowledge of aquifers in the study area. The use of electrical resistivity method which is the most commonly used geophysical method of groundwater exploration were employed in this study. In this electrical resistivity method, the use of Schlumberger array posed greater importance in delineating the aquifer parameters described by depth, thickness, transmissivity and hydraulic conductivity. Aquifer is described as geological formation capable of yielding economic quantity of water through recharge and discharge via water cycle. VES data of the nine (9) communities of Awka and environs at two locations each were plotted with IPI2WIN software and interpreted geologically and geophysically in subsections, the results revealed 4-6 layers. The nine (9) communities of Awka and environs were subdivided into zone A and zone B to enable easy work flow and pumping test analysis using the two existing borehole VES 4 and VES 14 data. -

Analysis of Land Use Dynamics of Awka South L.G.A Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 12, Issue 2 Ver. II (February. 2018), PP 67-72 www.iosrjournals.org Analysis Of Land Use Dynamics Of Awka South L.G.A Using Remote Sensing And Geographic Information System Ojiako, J.C, Igbokwe, E.C And UgwumbaR.J. Department of Surveying and GeoinformaticsNnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Nigeria Corresponding Author: Ojiako, J.C Abstract:This study is aimed at analysing the land use dynamics of Awka South L.G.A using Remote Sensing and GIS approach. The objectives were successfully completed byperforming multi-temporal analysis, deriving pattern and extent of development in Awka South using satellitedata of 1995, 2005 and 2016, and performing trend analysis of the derived development pattern. Using three multi-temporal sets of images (Landsat 5 TM, Landsat 7 ETM and Landsat 8 OLI) of 1995 to 2016, land usemaps of 1995, 2005 and 2016 were producedbyusingthe supervised maximum likelihoodclassification algorithmin ERDASImagine 9.1 and trend analysis was done to determine the trend of change and annual growth rate of landuse in the study area. Results showed that for the past 21 years, 1995-2016, Awka has been undergoing extensive land use change. The built up area in the city has grown from 13,693.85 hectares in 1995 to 16,993.58 hectares in 2005 and to 22,653.83hectares in 2016. The highest rate of urban growth is observed during the second period of urbanization (2005 to 2016) in which the built up area increased more than twice (46.10%) and in the first period of urbanization there was a change of 27.87%. -

Determinants and Prevalent Forms of Child Labour Practices in Awka South Local Government Area, Anambra State, South-East, Nigeria

ZIK Journal of Multidisciplinary Research: July 2021 Volume 4: 33-48 Determinants and Prevalent Forms of Child Labour Practices in Awka South Local Government Area, Anambra State, South-East, Nigeria. **Oli, Nneka Perpetua Department of Sociology/Anthropology Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Nweke, Chukwudi Kenneth Department of Sociology/Anthropology Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Email: [email protected] or [email protected] ** Corresponding Author Abstract This paper examined determinants and prevalent forms of child labour practices in Awka South Local Government Area, Anambra State, South-East, Nigeria. The study anchored on expectancy theory as its theoretical orientation. The target population consisted of only adults who were 18 years and above. The mixed methods research design was adopted in this study. A sample size of 200 was statistically generated using Taro Yamane formular. Multistage sampling procedure which involved simple random sampling and purposive sampling techniques were employed in selecting the study participants. The major instruments of data collection used were questionnaire schedule which is a quantitative method and in-depth interview guide which is a qualitative method. Self-administration was used in administering questionnaire to respondents. In conducting interviews, English language was used for the literate respondents while vernacular was used for the illiterate respondents. Quantitative data collected from the field study were processed with the use of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software. The qualitative data were analyzed using manual content analysis. Findings of the study indicated that determinants of child labour practices include poverty, educational level of parents, family size, cultural belief and living in slum area. -

Evaluation of Development Dynamics of Awka Capital Territory, Anambra State, Using Remote Sensing Igbokwe, E.C1, Emengini, E

ISSN XXXX XXXX © 2019 IJESC Research Article Volume 9 Issue No.4 Evaluation of Development Dynamics of Awka Capital Territory, Anambra State, using Remote Sensing Igbokwe, E.C1, Emengini, E. J2, Ojiako, J.C3 Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Nigeria Abstract: This study investigated the development dynamics of Awka Capital Territory in Anambra State, Nigeria using Remote Sensing. The objectives were to: examine the spatial extent of land cover and land use in Awka Capital Territory for the last 27 years (1990 – 2017); ascertain the trend of change, transition and pattern of the land cover/land use classes during this period and predict the future urban development dynamics for the next 30 years (2018 – 2048). The results revealed that urban area grew from 27.92% to 31.19%, to an of area of 14437.68 hectares between 1990 and 1999, 31.19% to 33.67%, to an area of 15586.73 hectares between 1999 and 2008, and 33.67% to 37.24%, to an area of 17237.45 hectares between 2008 and 2017. Trend of change analysis indicated that urban area had an annual rate of change of 0.62% between 1990 and 1999, 0.43% between 1999 and 2008 and 0.56% between 2008 and 2017. Transition results showed that between 1990 and 1999, urban area gained 1272.73 hectares from vegetation and 242.5 hectares from open space, also between 1999 and 2008 urban area gained 1000 hectares from vegetation and 149.05 hectares from open space, in the last epoch between 2008 and 2017 urban area gained 1068.27 hectares from vegetation, 582.45 hectares from open space.