A Study of Awka Metropolis Anambra State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

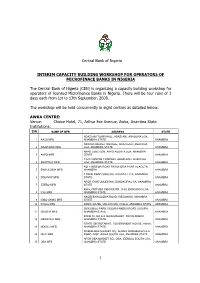

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 for Immediate Release U.S. Embassy

United States Diplomatic Mission to Nigeria, Public Affairs Section Plot 1075, Diplomatic Drive, Central Business District, Abuja Telephone: 09-461-4000. Website at http://nigeria.usembassy.gov PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 For Immediate Release U.S. Embassy Abuja Partners Channels Academy to Train Conflict Reporters The U.S. Embassy Abuja, in partnership with Channels Academy, has trained over 150 journalists on Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism. In her opening remarks, the U.S. Embassy Spokesperson/Press Attaché Jeanne Clark noted that the United States recognized that security challenges exist in many forms throughout the country, and that journalists are confronted with responsibility to prioritize physical safety in addition to meeting standards of objectivity and integrity in conflict. She urged the journalists to share their experiences throughout the course of the three-day seminar and encouraged participants to identify new ways to address these security challenges. The trainer Professor Steven Youngblood from the U.S. Center for Global Peace Journalism – Park University defined and presented principles for peace journalism in conflict reporting. He cautioned journalists to refrain from what he termed war journalism. He said, "war journalism is a pattern of media coverage that includes overvaluing violent, reactive responses to conflict while undervaluing non-violent, developmental responses.” The Provost of Channels Academy, Mr Kingsley Uranta, showed appreciation for the continuous partnership with the U.S. Embassy and for bringing such training opportunities to Nigerian journalists. He also called on conflict reporters to be peace ambassadors. The training took place virtually via Zoom on June 22 – 24, 2021. Journalists converged in American Spaces in Abuja, Kano, Bauchi Sokoto, Maiduguri, Awka, and Ibadan. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

Fault Detection on Power System Transmission Line Using Artificial Neural Network (A Comparative Case Study of Onitsha – Awka – Enugu Transmission Line

American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 2019 American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) e-ISSN: 2320-0847 p-ISSN : 2320-0936 Volume-8, Issue-4, pp-32-57 www.ajer.org Research Paper Open Access Fault Detection on Power System Transmission Line Using Artificial Neural Network (A Comparative Case Study of Onitsha – Awka – Enugu Transmission Line V. C. Ogboh1., E. C. Nwangugu2., A. E. Anyalebechi3 1Department of Electrical of Engineering, NnamdiAzikiwe University Awka.Anambra State Nigeria 2Department of Electrical of Engineering, NnamdiAzikiwe University Awka.Anambra State Nigeria 3Department of Electrical of Engineering, NnamdiAzikiwe University Awka.Anambra State Nigeria Corresponding Author; V. C. Ogboh ABSTRACT:This paper dwelt on the use of artificial neural network (ANN) method with Matlab Simulink 2016 to detect faults on the power system transmission line using Onitsha – Awka – Enugu as a cast study. The Onitsha - Awka – Enugu transmission line was modeled with Matlab Simulink 2016 using the transmission line pre-fault and daily fault data. Single line to ground (A – G), Double line to ground (AB – G), Line to line (A – B) and three phase (ABC) faults were simulated with the ANN method using Matlab Simulink 2016. However, the ANNshow detail detection and analysis of faults on the line. It was able to detect faults, classify them and locate thefault distance. The output results of the method where compared with the symmetrical component method (the conventional method). The comparison was done based on robustness/simplicity, less error, accuracy and efficiency. ANN was found the best in terms of the above comparative factors. KEYWORDS: Fast Fourier Transform, Wavelet Transform, Artificial Neural Network, Symmetrical Components, Travelling Wave. -

THE ARCHITECTURE of the URBAN FRONTS, the CASE of URBAN EXPERIENCE and PRESSURE on the INFRASTRUCTURE -- Bons N

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.7, No.2. June 2018 THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE URBAN FRONTS, THE CASE OF URBAN EXPERIENCE AND PRESSURE ON THE INFRASTRUCTURE -- Bons N. Obiadi, Nzewi, N.U. The Architecture of the Urban Fronts, the Case of Urban Experience and Pressure on the Infrastructure. Bons N. Obiadi Department of Architecture Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka and Nzewi, N.U. Department of Architecture Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract: A generalized perception of Architecture locates the discipline within the narrow boundaries of design and erection of buildings. While this may be acceptable in certain quarters, the fact remains that the spatial emergence and generic function guiding the relationship between human beings and space have, for centuries, guided the architecture of cities. Architecture, according to definitions, is practiced by licensed professionals in the industry however; literature has proven that almost everyone practices architecture in different ways and not, exclusively limiting to the design and erection of buildings. The dumping of communities solid wastes redefine the configuration of the area's environment and it is architectural, and deals with human beings and spaces. The design, construction and erection of roads, bridges and community street security gates are architectural and negatively impacting on the environment and particularly, architecture of the area. Objectively, the aim of this study is to create awareness and point to the fact, that the Nigerian players (policy makers) have in the past, designed models to direct positive growth and development in the country, but failed to properly implement the programmes and that is detrimental to the country's built environment and especially, architecture and infrastructure. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Household Water Demand in the Peri-Urban Communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria

Vol. 6(6), pp. 237-243, August, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/JGRP2013.0385 Journal of Geography and Regional Planning ISSN 2070-1845 © 2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP Full Length Research Paper Household water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka, Capital of Anambra State, Nigeria E. E. Ezenwaji1*, P.O. Phil-Eze2, V. I. Otti3 and B. M. Eduputa4 1Department of Geography and Meteorology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria. 3Civil Engineering Department, Federal Polytechnic, Oko, Nigeria. 4Department of Environmental Management, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria. Accepted 22 July, 2013 The aim of this paper is to determine relevant factors contributing to the water demand in the peri-urban communities of Awka capital city. Towards achieving this aim, questionnaire were developed and served on the households in various communities to collect relevant data on the 13 physical and socio- economic factors we earlier identified as influencing water demand in the area. Water quality was ascertained through microbiological analysis of water samples. The major analytical techniques used were multiple correlations, the result of which was subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression. Result shows that the 13 variables combined to contribute 90.0% of water demand in the area. Furthermore, the low standard error of estimates of 0.029 litres shows that water demand in the communities could be predicted using the 13 variables. Policy and planning measures to improve the water supply situation of the area were suggested. Key words: Capital, communities, factors, peri-urban, water demand. -

A Case Study of Awka and Onitsha in Anambra State, Nigeria

Journal of Law, Policy and Globalization www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3240 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3259 (Online) Vol.19, 2013 Urban Flooding and Vulnerability of Nigerian Cities: A Case Study of Awka and Onitsha in Anambra State, Nigeria Kingsley Efobi * Christopher Anierobi Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Nigeria, Enugu campus PMB 01129,Nigeria * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The climate change phenomenon with its associated increase in global temperature, precipitation and rise in sea levels has also ushered in an increased frequency of flooding in recent times. In the year 2012, many Nigerian cities suffered from the ravaging effects of flooding. This led to lose of lives, internal displacements, destruction of properties, disruption of socio-economic, cultural and religious activities; and splintering of family ties. The cities of Awka and Onitsha in Anambra state, Nigeria featured among the vulnerable cities which are susceptible to flooding. This study set out to find out the causes of flooding in these cities with a view to recommending measures that will help ameliorate the situation. Direct observations and structured interview methods were used to acquire the needed primary data from residents of identified flood prone areas and in addition to secondary data obtained from official records of the State Ministry of Environment. The result revealed that although flooding gives the residents of Awka and Onitsha nightmares, especially during the rainy seasons; it had received only 15% of government intervention activities on environmental problems. There is gross inadequacy in the provision of drainage channels, coupled with poor designs, poor construction and blocked drainage channels. -

Christianity and Awka Socio-Religio-Cultural Identity Crisis: Areas of Conflict

CHRISTIANITY AND AWKA SOCIO-RELIGIO-CULTURAL IDENTITY CRISIS: AREAS OF CONFLICT Patrick Enoch Nmah http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/og.v12i s1.5 Abstract The problem of religious and cultural conflict still baffles many scholars of religion, sociology and anthropology. This article was designed to investigate and x-ray critically the religious values, beliefs and practices among the Awka people of Nigeria that were involved in the socio-religious conflict. Findings showed that the issues involved in the conflict were the Imo Awka festival, burial rites ( ikponye aja n’ili - dust-to-dust rite), and okuko onye uwa (hen sacrificed to family deity to validate a marriage bond). It was recommended among others that the church and Awka people should in the way of resolving conflict situation use the least expensive method without much acrimony. The main aim of this research was to shed some light on the consequences of this socio-religio-cultural conflict. The method applied in the research work was historio- phenomenological approach with the review of related literature. Introduction This article aims at articulating the socio-religious and cultural conflicts associated with Imoka festival, burial rites and okukoonyeuwa (hen sacrificed to idol) in Awka. There is the need to give accurate information that will correct the misinterpretation and misinformation going round in the Awka in respect of the three issues raised above. The significance of the research is that it will be useful for academic knowledge and practical aims. The method applied is historio-phenomenological approach. Related extant materials were used in the course of the research.In summary, what is being said is that every community has its own religion. -

CHRISTIANITY of CHRISTIANS: an Exegetical Interpretation of Matt

CHRISTIANITY OF CHRISTIANS: An Exegetical Interpretation of Matt. 5:13-16 And its Challenges to Christians in Nigerian Context. ANTHONY I. EZEOGAMBA Copyright © Anthony I. Ezeogamba Published September 2019 All Rights Reserved: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. ISBN: 978 – 978 – 978 – 115 – 7 Printed and Published by FIDES MEDIA LTD. 27 Archbishop A.K. Obiefuna Retreat/Pastoral Centre Road, Nodu Okpuno, Awka South L.G.A., Anambra State, Nigeria (+234) 817 020 4414, (+234) 803 879 4472, (+234) 909 320 9690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.fidesnigeria.com, www.fidesnigeria.org ii DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to my dearest mother, MADAM JUSTINA NKENYERE EZEOGAMBA in commemoration of what she did in my life and that of my siblings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge the handiwork of God in my life who is the author of my being. I am grateful to Most Rev. Dr. S.A. Okafor, late Bishop of Awka diocese who gave me the opportunity to study in Catholic Institute of West Africa (CIWA) where I was armed to write this type of book. I appreciate the fatherly role of Bishop Paulinus C. Ezeokafor, the incumbent Bishop of Awka diocese together with his Auxiliary, Most Rev. Dr. Jonas Benson Okoye. My heartfelt gratitude goes also to Bishop Peter Ebele Okpalaeke for his positive influence in my spiritual life. I am greatly indebted to my chief mentor when I was a student priest in CIWA and even now, Most Rev.