Alexander Von Humboldt's Views of the Cultures of the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Session Abstracts for 2013 HSS Meeting

Session Abstracts for 2013 HSS Meeting Sessions are sorted alphabetically by session title. Only organized sessions have a session abstract. Title: 100 Years of ISIS - 100 Years of History of Greek Science Abstract: However symbolic they may be, the years 1913-2013 correspond to a dramatic transformation in the approach to the history of ancient science, particularly Greek science. Whereas in the early 20th century, the Danish historian of sciences Johan Ludvig Heiberg (1854-1928) was publishing the second edition of Archimedes’ works, in the early 21st century the study of Archimedes' contribution has been dramatically transformed thanks to the technological analysis of the famous palimpsest. This session will explore the historiography of Greek science broadly understood during the 20th century, including the impact of science and technology applied to ancient documents and texts. This session will be in the form of an open workshop starting with three short papers (each focusing on a segment of the period of time under consideration, Antiquity, Byzantium, Post-Byzantine period) aiming at generating a discussion. It is expected that the report of the discussion will lead to the publication of a paper surveying the historiography of Greek science during the 20th century. Title: Acid Rain Acid Science Acid Debates Abstract: The debate about the nature and effect of airborne acid rain became a formative environmental debate in the 1970s, particularly in North America and northern Europe. Based on the scientific, political, and social views of the observers, which rationality and whose knowledge one should trust in determining facts became an issue. The papers in this session discuss why scientists from different countries and socio-political backgrounds came to different conclusions about the extent of acidification. -

Calendrical Calculations: the Millennium Edition Edward M

Errata and Notes for Calendrical Calculations: The Millennium Edition Edward M. Reingold and Nachum Dershowitz Cambridge University Press, 2001 4:45pm, December 7, 2006 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. Unless otherwise indicated, line counts used in describing the errata are positive counting down from the first line of text on the page, excluding the header, and negative counting up from the last line of text on the page including footnote lines. -

Culture Box Aims to Provide Resources for Approaching Mexico in a Multidisciplinary Way, Featuring Items That Tell Stories of Mexico’S Past and Present

MEXICO INTRODUCTION: Mexico is the large country that shares a common border with the United States about 2,000 miles long. Ancient ruins such as Teotihuacan (Aztec) and Chichen Itza (Mayan) are scattered throughout the country. This culture box aims to provide resources for approaching Mexico in a multidisciplinary way, featuring items that tell stories of Mexico’s past and present. WHAT THIS BOX INCLUDES: 1. Copper Plate 2. Mexican Peso, Woven Coin Purse 3. Miniature Tamale 4. Miniature Indigenous Women 5. Game – Loteria (2) 6. Muñeca Maria 7. Spanish Vocabulary Cards 8. La Virgen de Guadalupe 9. Oaxacan Crafted Turtle 10. Clay Pendants 11. Aztec Calendar 12. Tablitas Mágicas 13. Maracas 14. Spin Drum Culture Box: Mexico COPPER PLATE DESCRIPTION This copper plate features the Aztec calendar. This sort of plate is sold in gift shops and can be used as decoration. The Aztec calendar is the system that was used by Pre-Columbian people of Central Mexico, and is still used by Nahuatl speaking people today. There are two types of Aztec calendars: the sacred calendar with 260 days (tonalpohualli in Nahuatl); and the agricultural calendar with 365 days (xiuhpohualli in Nahuatl). The tonalpohualli is regarded as the sacred calendar because it divides the days and rituals between the Aztec gods. According to the Aztecs, the universe is very delicate and equilibrium is in constant danger of being disrupted, and the calendar tells how time is divided between the gods. Culture Box: Mexico MEXICAN PESO, COIN PURSE DESCRIPTION The Mexican Peso is one of the oldest currencies in North America. -

Selling Mexico: Race, Gender, and American Influence in Cancún, 1970-2000

© Copyright by Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 ii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _________________________ Tracy A. Butler APPROVED: _________________________ Thomas F. O’Brien Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ John Mason Hart, Ph.D. _________________________ Susan Kellogg, Ph.D. _________________________ Jason Ruiz, Ph.D. American Studies, University of Notre Dame _________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics iii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 iv ABSTRACT Selling Mexico highlights the importance of Cancún, Mexico‘s top international tourism resort, in modern Mexican history. It promotes a deeper understanding of Mexico‘s social, economic, and cultural history in the late twentieth century. In particular, this study focuses on the rise of mass middle-class tourism American tourism to Mexico between 1970 and 2000. It closely examines Cancún‘s central role in buttressing Mexico to its status as a regional tourism pioneer in the latter half of the twentieth century. More broadly, it also illuminates Mexico‘s leadership in tourism among countries in the Global South. -

Planetary Science : a Lunar Perspective

APPENDICES APPENDIX I Reference Abbreviations AJS: American Journal of Science Ancient Sun: The Ancient Sun: Fossil Record in the Earth, Moon and Meteorites (Eds. R. 0.Pepin, et al.), Pergamon Press (1980) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 13 Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal Apollo 15: The Apollo 1.5 Lunar Samples, Lunar Science Insti- tute, Houston, Texas (1972) Apollo 16 Workshop: Workshop on Apollo 16, LPI Technical Report 81- 01, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston (1981) Basaltic Volcanism: Basaltic Volcanism on the Terrestrial Planets, Per- gamon Press (1981) Bull. GSA: Bulletin of the Geological Society of America EOS: EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union EPSL: Earth and Planetary Science Letters GCA: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta GRL: Geophysical Research Letters Impact Cratering: Impact and Explosion Cratering (Eds. D. J. Roddy, et al.), 1301 pp., Pergamon Press (1977) JGR: Journal of Geophysical Research LS 111: Lunar Science III (Lunar Science Institute) see extended abstract of Lunar Science Conferences Appendix I1 LS IV: Lunar Science IV (Lunar Science Institute) LS V: Lunar Science V (Lunar Science Institute) LS VI: Lunar Science VI (Lunar Science Institute) LS VII: Lunar Science VII (Lunar Science Institute) LS VIII: Lunar Science VIII (Lunar Science Institute LPS IX: Lunar and Planetary Science IX (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute LPS X: Lunar and Planetary Science X (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XI: Lunar and Planetary Science XI (Lunar and Plane- tary Institute) LPS XII: Lunar and Planetary Science XII (Lunar and Planetary Institute) 444 Appendix I Lunar Highlands Crust: Proceedings of the Conference in the Lunar High- lands Crust, 505 pp., Pergamon Press (1980) Geo- chim. -

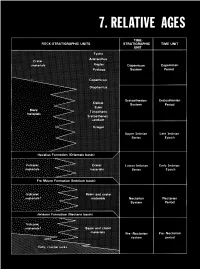

Relative Ages

CONTENTS Page Introduction ...................................................... 123 Stratigraphic nomenclature ........................................ 123 Superpositions ................................................... 125 Mare-crater relations .......................................... 125 Crater-crater relations .......................................... 127 Basin-crater relations .......................................... 127 Mapping conventions .......................................... 127 Crater dating .................................................... 129 General principles ............................................. 129 Size-frequency relations ........................................ 129 Morphology of large craters .................................... 129 Morphology of small craters, by Newell J. Fask .................. 131 D, method .................................................... 133 Summary ........................................................ 133 table 7.1). The first three of these sequences, which are older than INTRODUCTION the visible mare materials, are also dominated internally by the The goals of both terrestrial and lunar stratigraphy are to inte- deposits of basins. The fourth (youngest) sequence consists of mare grate geologic units into a stratigraphic column applicable over the and crater materials. This chapter explains the general methods of whole planet and to calibrate this column with absolute ages. The stratigraphic analysis that are employed in the next six chapters first step in reconstructing -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

Ralph Bauer Associate Dean for Academic

CURRICULUM VITAE Ralph Bauer Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, College of Arts and Humanities Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature 1102 Francis Scott Key Hall University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-7311 Phone: 301 405 5646 E-Mail: [email protected] https://www.english.umd.edu/profiles/rbauer ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: August 2004 to present: Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature, University of Maryland. May – July 2011: Visiting Professor, American Studies, University of Tuebingen. August 2006 to August 2007: Associate Visiting Professor, Department of English and Department of Spanish and Portuguese, New York University June 2006 to July 2006: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of American Studies, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany. August 1998- August 2004: Assistant Professor of English, University of Maryland. August 1997- August 1998: Assistant Professor of English, Yale University. 1992-1996 Graduate Instructor, Michigan State University, Department of English, Department of American Thought and Language, Department of Integrative Studies in Arts and Humanities. ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS: August 2017 to present: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, College of Arts and Humanities. 20013-2016: Director of Graduate Studies, Department of English, University of Maryland, College Park 2003 -2006: Director of English Honors, University of Maryland, College Park. EDUCATION: Ph. D., American Studies, 1997, Michigan State University. M. A., American Studies, 1993, Michigan State University. Undergraduate Degrees (Zwischenpruefung), 1991, in English, German, and Spanish, University of Erlangen/Nuremberg, Germany. SCHOLARSHIP: MONOGRAPHS: The Alchemy of Conquest: Science, Religion, and the Secrets of the New World (forthcoming from the University of Virginia Press, fall 2019). The Cultural Geography of Colonial American Literatures: Empire, Travel, Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003; paperback 2008). -

PEZ CAPITÁN DE LA SABANA (Eremophilus Mutisii)

PROGRAMA NACIONAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LA ESPECIE ENDÉMICA DE COLOMBIA PEZ CAPITÁN DE LA SABANA (Eremophilus mutisii) SECRETARÍA DISTRITAL DE AMBIENTE MINISTERIO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE - MINAMBIENTE Ministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible Luis Gilberto Murillo Urrutia Viceministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible Carlos Alberto Botero López Director de Bosques, Biodiversidad y Servicios Ecosistémicos César Augusto Rey Ángel Grupo de Gestión en Biodiversidad Carolina Avella Castiblanco Óscar Hernán Manrique Betancour Natalia Garcés Cuartas SECRETARÍA DISTRITAL DE AMBIENTE - SDA Secretario Distrital de Ambiente Francisco José Cruz Prada Directora de Gestión Ambiental Empresarial Adriana Lucía Santa Méndez Subdirectora de Ecosistemas y Ruralidad (E) Patricia María González Ramírez Wendy Francy López Meneses - Coordinadora de Monitoreo de Biodiversidad Patricia Elena Useche Losada - Coordinadora Humedales UNIVERSIDAD MANUELA BELTRÁN - UMB Juan Carlos Beltrán – Gerente institucional Ciromar Lemus Portillo – Profesor investigador Mónika Echavarría Pedraza – Profesora investigadora Carlos H. Useche Jaramillo – Profesor Centro de Estudios en Hidrobiología SECRETARÍA DISTRITAL DE AMBIENTE Diana Villamil Pasito – Ingeniera ambiental Hernando Baquero Gamboa – Ingeniero ambiental Kelly Johana León – Ingeniera ambiental UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA Y TECNOLÓGICA DE COLOMBIA Nelson Javier Aranguren Riaño – Profesor INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS NATURALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA José Carmelo Murillo Aldana – Director José Iván -

German Views of Amazonia Through the Centuries

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2012 German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries Richard Hacken [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hacken, Richard, "German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries" (2012). Faculty Publications. 2155. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/2155 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. German Views of Amazonia through the Centuries Amazonia has been called “…the most exuberant celebration of life ever to have existed on earth.”i It has been a botanical, zoological and hydrographic party for the ages. Over the past five centuries, German conquistadors, missionaries, explorers, empresses, naturalists, travelers, immigrants and cultural interpreters have been conspicuous among Europeans fascinated by the biodiversity and native peoples of an incomparably vast basin stretching from the Andes to the Atlantic, from the Guiana Highlands to Peru and Bolivia, from Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador to the mouth of the Amazon at the Brazilian equator. Exactly two thousand years ago, in the summer of the year 9, a decisive victory of Germanic tribes over occupying Roman legions took place in a forest near a swamp. With that the Roman Empire began its final decline, and some would say the event was the seed of germination for the eventual German nation. -

The Mayan Long Count Calendar Thomas Chanier

The Mayan Long Count Calendar Thomas Chanier To cite this version: Thomas Chanier. The Mayan Long Count Calendar. 2015. hal-00750006v12 HAL Id: hal-00750006 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00750006v12 Preprint submitted on 16 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Mayan Long Count Calendar Thomas Chanier∗1 1 Universit´ede Bretagne Occidentale, 6 avenue Victor le Gorgeu, F-29285 Brest Cedex, France The Mayan Codices, bark-paper books from the Late Postclassic period (1300 to 1521 CE) contain many astronomical tables correlated to ritual cycles, evidence of the achievement of Mayan naked- eye astronomy and mathematics in connection to religion. In this study, a calendar supernumber is calculated by computing the least common multiple of 8 canonical astronomical periods. The three major calendar cycles, the Calendar Round, the Kawil and the Long Count Calendar are shown to derive from this supernumber. The 360-day Tun, the 365-day civil year Haab' and the 3276-day Kawil-direction-color cycle are determined from the prime factorization of the 8 canonical astronomical input parameters. The 260-day religious year Tzolk'in and the Long Count Periods (the 360-day Tun, the 7200-day Katun and the 144000-day Baktun) result from arithmetical calculations on the calendar supernumber.