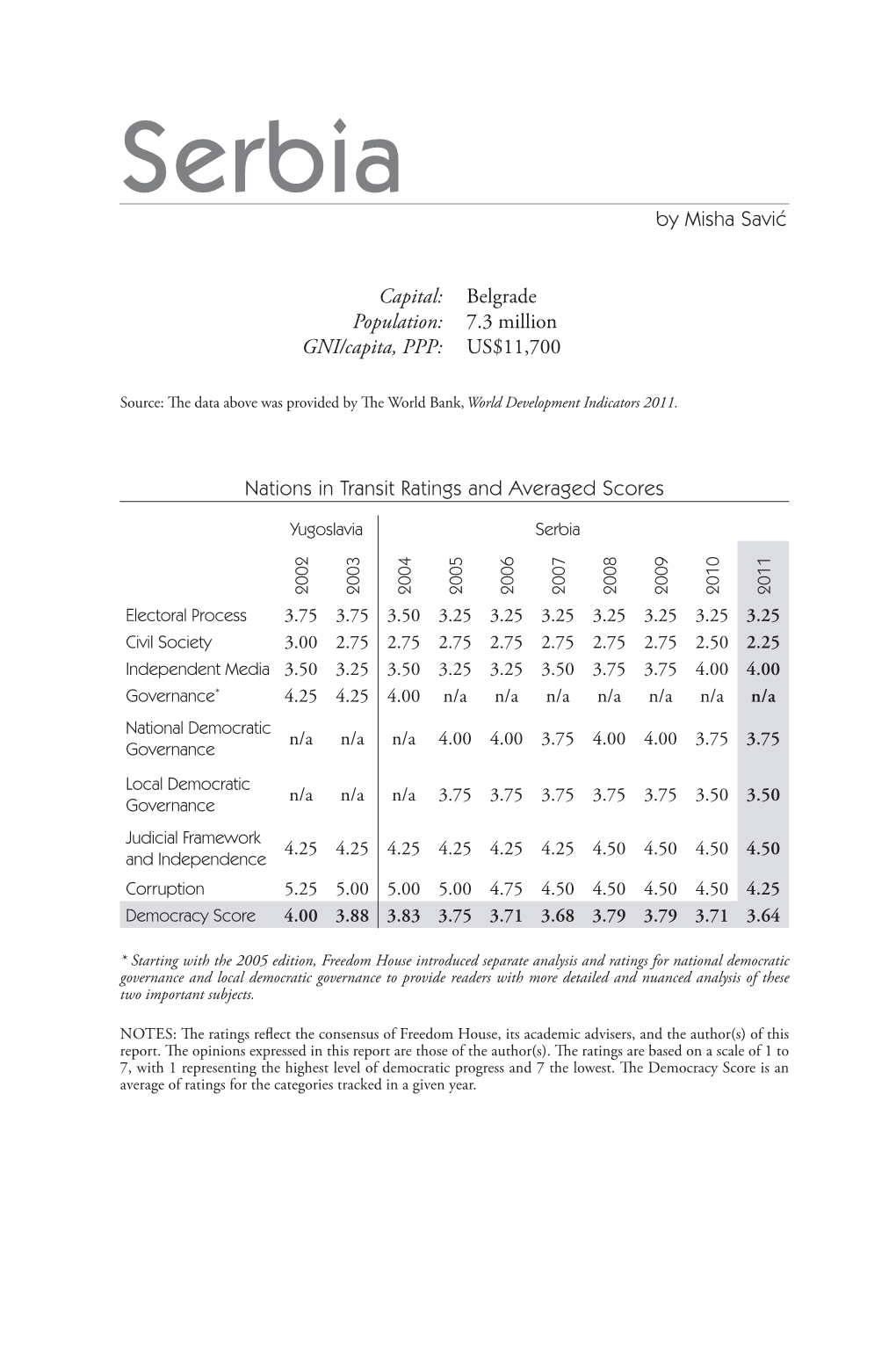

Serbia by Misha Savic´

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jenő Hajnal: National Identity Is Our Most Valuable Treasure

Minister Ružić Meets with Representatives of Europe Insists on Rights of the National Minority National Minorities – Councils Serbia Respects These Rights 38 Minority Newjuly 2s 017 Jenő Hajnal: National Identity Is Our Most Valuable Treasure Participants in the Regional “Rose”- a Symbol NDI Roma Program Visit the and First Association Assembly of AP Vojvodina with Ruthenians HIGHLIGHT EDITORIAL 38 Minister Ružić Meets with Repre sentatives Rich ness i n Diver sity of the National Minority Do bar dan, mi rëdita, jó na pot, добър ден, bun ă ziua... B u njevac Councils Dužijan ca, Rut henian “Red Rose“, uniq ue Vlach customs , Rom a music , colourfu l Slovak natio na l costumes, kulen saus a ge from On July 25, in the Pal ace Serbia, Minister of Public Administration and Local Self- Pet rovac… – are on ly few of the featur es of the multina tional and m ulti cultural m osa ic of ou r coun try . Gover nment, Brank o Ruž ić, met with the represe ntatives of the natio na l mi - There is n o nee d to em phasize that nu merous minorities have nority co uncils in o rder to be i nformed lived in these lands together for centuries. Our politicians and about t he activ ities of the n ational mi - numero us foreign v isit ors fre quently p oint to th is fa ct. T he Au - nority counc ils an d the mo st imp ortant tonomous Province of Vojvodina is an unique example of multi - challenges they face in their work. -

Branko Ružić: This Is the Year of National Minorities

As a State, We 74 Projects for Better Nourish the Unity Information in the Languages of Diversity of National Minorities Funded 49 Minority Neseptwember 2s 018 Branko Ružić: This Is the Year of National Minorities The Slovenian Community Hungarian from Serbia at the Bled Cultural Society Strategic Forum "Karika" Opened HIGHLIGHTS EDITORIAL 49 Government Committed to Improvi ng the Status (N ot) the choic e? of Minority Rights The re is a bit m ore than a m onth left until the elec tions for m e mbers On Septe mber 6, the Directo r of the Go - of natio nal cou ncils o f national mi nori ties . The m ember s of t he vernment Offic e for Hu m an and M inority 22 nat ional min orities will be e xercising the ir right to e l ect their Rights, Suza na Paunov ić, met with the OSCE rep resentatives . The first p recondit ion fo r vo ting is to enrol in the High Com missioner for Natio nal M inorities, Speci al Vo ters’ List fo r Na tional M inorit ies . Acco rd ing to the w ebsi te Lambe rto Zannier, an d she i nformed him about the im plementa tion of the a cti vities of the Min istry of Public A dminist ration an d Local Self-Government, of the Ac tion Plan fo r the Realizat ion of the the conclusion of the Special Voter List will be done 15 days before Rights o f Nationa l Minorities. -

Serbia in 2001 Under the Spotlight

1 Human Rights in Transition – Serbia 2001 Introduction The situation of human rights in Serbia was largely influenced by the foregoing circumstances. Although the severe repression characteristic especially of the last two years of Milosevic’s rule was gone, there were no conditions in place for dealing with the problems accumulated during the previous decade. All the mechanisms necessary to ensure the exercise of human rights - from the judiciary to the police, remained unchanged. However, the major concern of citizens is the mere existential survival and personal security. Furthermore, the general atmosphere in the society was just as xenophobic and intolerant as before. The identity crisis of the Serb people and of all minorities living in Serbia continued. If anything, it deepened and the relationship between the state and its citizens became seriously jeopardized by the problem of Serbia’s undefined borders. The crisis was manifest with regard to certain minorities such as Vlachs who were believed to have been successfully assimilated. This false belief was partly due to the fact that neighbouring Romania had been in a far worse situation than Yugoslavia during the past fifty years. In considerably changed situation in Romania and Serbia Vlachs are now undergoing the process of self identification though still unclear whether they would choose to call themselves Vlachs or Romanians-Vlachs. Considering that the international factor has become the main generator of change in Serbia, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia believes that an accurate picture of the situation in Serbia is absolutely necessary. It is essential to establish the differences between Belgrade and the rest of Serbia, taking into account its internal diversities. -

Turkey's Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Bosnia-Herzegovina

Turkey’s Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandžak (2002 -2017) Jahja Muhasilović Istanbul, 2020 Turkey’s Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandžak (2002 -2017) Union of Turkish World Municipalities (TDBB) Publications, No: 30 ISBN 978-605-2334-08-9 Book Design and Technical Preparation Murat Arslan Printing Imak Ofset Tel: +90 212 656 49 97 Istanbul, 2020 Union of Turkish World Municipalities (TDBB) reserves all rights of the book‘Turkey’s Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Bosnia- Herzegovina and Sandžak (2002 -2017). It can be just quoted by providing reference. None of the parts in this book can be reprinted and reproduced without permission. Merkez Efendi Mah. Merkez Efendi Konağı No: 29 Zeytinburnu 34015 İstanbul Tel +90 212 547 12 00 www.tdbb.org.tr Jahja Muhasilovic Jahja Muhasilovic was born in 1987 in Sarajevo, Bos- nia and Herzegovina. Alumni of Bogazici University he is fluent in local Balkans languages and Turkish. His primary expertise is on Turkish foreign policy in the Balkans. A graduate of history at the Universty of Sarajevo he special- ized in modern politics and soft power during his Ph.D. studies. Muhasilovic also authored many books, scientific articles, and opinion columns on Turkey’s influence in the Balkans for different regional and international publishers and media outlets. His ex- perience in working for media both regional and Turkish has provided him a good un- derstanding of Balkan politics and Turkey’s role in it. The book Turkey’s Soft Power and Public Diplomacy in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandžak (2002-2017) is just one of those works that evaluate a highly polarized subject of Turkey’s foreign policy in the Balkans. -

Sandzak – a Region That Is Connecting Or Dividing Serbia and Montenegro?

SANDZAK – A REGION THAT IS CONNECTING OR DIVIDING SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO? Sandzak is a region that is divided among Serbia and Montenegro. Six municipalities are in Serbia (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Prijepolje, Priboj and Nova Varoš) and six in Montenegro (Bijelo Polje, Rožaje, Berane, Pljevlja, Gusinje and Plav). On the basis of the 1991 census the number of the inhabitants of Sandzak included 420.000 people – 278.000 in Serbia and 162.000 in Montenegro, of which 54% are Muslims by ethnicity. Sandzak, which is carrying its name after a Turkish word for a military district, constituted a part of the Bosnian Pashalik within the Ottoman Empire until the year 1878. On the Berlin Congress, which was held at the same year, the great powers decided to leave Sandzak within the framework of the Ottoman Empire, but have allowed Austro- Hungary to deploy their forces in a part of this region. Through an agreement between the kings of Serbia Peter I. Karadjordjevic and of Montenegro Nikola I. Petrovic, but thanks to Russia, Serbia and Montenegro took control over Sandzak in the First Balkan War of 1912. Up to the Balkan Wars in 1912 and 1913, Sandzak represented a separate administrative unit with the administration and cultural center being in Novi Pazar. After the end of the Balkan Wars the process of emigration of the Bosniac population to Turkey continued and through the port of Bar left for Turkey in the period between April and June 1914 some 16.500 Bosniacs from the Montenegrin part of Sandzak and some 40.000 from the Serbian part. -

Serbia Political Briefing: Kosovo and Metohija - a New Dynamics of the Negotiation Process IIPE

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 10, No. 1 (RS) September 2018 Serbia Political briefing: Kosovo and Metohija - a new dynamics of the negotiation process IIPE 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu Kosovo and Metohija - a new dynamics of the negotiation process The most important political topic in July and August were proposed solutions within the negotiation process between Belgrade and Pristina, which had negative odium in numerous actors of the international community, representatives of the opposition and the Serbian Orthodox Church. This phase of the dialogue was marked with more concrete solutions, but also contradictory and vague statements by officials. Regarding the process of European integration major topic was harmonization of the constitutional amendments with the opinion of the Venice Commission. In early July, Hashim Thaci made a statement in which he highlighted demand for direct participation of the United States in the negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina. Shortly after this statement, Prime Minister Ana Brnabic's replied stressing that in the case of USA participation in negotiations, the same status must be secured to other actors, such as Russia and China. On this matter, the European Foreign Service stated that the European Union opposes changing the format of the dialogue, because the participation of the US as a new actor would lead to Russia's engagement in dialogue, which would significantly affect the speed and efficiency of the entire process. Speaking about the method of implementation of the agreement on Kosovo and Metohija, President of Serbia stated on July 8th that any solution reached during the negotiations must be confirmed in a referendum. -

Serbian and Montenegrin Authorities Have Stepped up Oppression of Non-Serbs in Serbia and Montenegro

May 1994 Vol. 6, Issue 6 Human Rights Abuses of NonNon----SerbsSerbs 111 In Kosovo, Sandñññak and Vojvodina With the world's attention distracted by events in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Serbian and Montenegrin authorities have stepped up oppression of non-Serbs in Serbia and Montenegro. In particular, incidents of police abuse, arbitrary arrests and abuse in detention have been prevalent in the three regions of Serbia and Montenegro in which non-Serbs constitute a majority or significant minority: Kosovo (a province of Serbia which is 90 percent ethnic Albanian), Sandñak (a region of Serbia and Montenegro which is over 50 percent Muslim) and Vojvodina (a province of Serbia which is approximately 19 percent ethnic Hungarian, 5.4 percent Croat and 3.4 percent Slovak).2 The governments of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia3 and Serbia have done little or nothing to curb human rights abuses in their own territory. Instead, the authorities have at times directly participated in the abuse C through direction, control and support of the police, army, paramilitary, and judiciary C and, at other times, condoned the abuse by failing to investigate and prosecute cases of abuse by armed civilians and paramilitary squads. 1 This statement was submitted to the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe on May 6, 1994. 2 Note that approximately 8 percent of Vojvodina's population identified themselves as "Yugoslav" in the 1991 census. 3 "Yugoslavia" refers to the self-proclaimed Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the union of Serbia (including the provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo) and Montenegro. Although claiming successor status to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia has not been internationally recognized as a successor state to the SFRY. -

ENGLISH Only

13th Economic Forum Prague, 23 – 27 May 2005 EF.NGO/25/05 25 May 2005 ENGLISH only Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia Annual Report 2004. Sandzak: Still a Vulnerable Region Sandzak covers a large area between Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is administratively divided by the two state-members of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. Serbia runs 6 Sandzak municipalities (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Priboj, Prijepolje and Nova Varos), and Montenegro runs 5 (Bijelo Polje, Rozaje, Plav, Pljevlja and Berane). That administrative divison was put in place after then end of the First Balkans War in 1912. Before that war Sandzak made part of the Ottoman Empire. That region did not have a special status or enjoyed any form of autonomy in former Yugoslavia, or after its administrative division. Nonetheless Bosniak population of Sandzak has a strong feeling of regionalism. Serbs living in that region tend to call it the Raska area and consider it a cradle of the Serb statehood. In the vicinity of Novi Pazar once existed Ras, the first Serb medieval state with its renowned monasteries of Sopocani and Djurdjevi stupovi. Bosniaks account for 80% of Novi Pazar population, 97% of Tutin population, 85% of Sjenica denizens, 40% of Prijepolje denizens, 10% of Priboj population, 8% of Nova Varos population, 95% of Rozaje locals, 45% of Bijelo Polje denizens, 80% of Plav locals, 30% of Pljevlja population, and 30% of Berane locals. According to the 2002 census total population of the Serb part of Sandzak is 235,567, of whom 132, 350, are Bosniak Muslims (a vast majority of members of that people at the census declared themselves as Bosniaks, while only a small number of them declared themselves as Muslims. -

Serbia's Sandzak: Still Forgotten

SERBIA'S SANDZAK: STILL FORGOTTEN Europe Report N°162 – 8 April 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. SANDZAK'S TWO FACES: PAZAR AND RASCIA ................................................ 2 A. SEEKING SANDZAK ...............................................................................................................2 B. OTTOMAN SANDZAK.............................................................................................................3 C. MEDIEVAL RASCIA ...............................................................................................................4 D. SERBIAN SANDZAK ...............................................................................................................4 E. TITOISM ................................................................................................................................5 III. THE MILOSEVIC ERA ................................................................................................ 7 A. WHAT'S IN A NAME? .............................................................................................................7 B. COLLIDING NATIONALISMS...................................................................................................8 C. STATE TERROR ...................................................................................................................10 -

Hajriz Kolašinac, Fadil Ugljanin, Hajro Aljkovi, Demail Etemovi, Šefet Graanin, Nedib Dipko Hodi

EXTERNAL AI Index: EUR 70/20/96 Action Ref: AF 371/95 September 1996 UPDATE : HAJRIZ KOLAŠINAC AND CO-DEFENDANTS RELEASED AFTER SUPREME COURT ORDERS RE-TRIAL Released in March 1996: Hajriz Kolašinac, Fadil Ugljanin, Hajro Aljkovi, Demail Etemovi, Šefet Graanin, Nedib Dipko Hodi Released in October 1994 pending appeal: Hodo Jakupovi, Ibrahim Fakovi, Alija Halilovic, Jonuz Škrijelj, Šefkija Rašljanin, Rifat Dupljak, Jakup Hodi ,Safet Zilki, Adem Hasi, Mustafa Ali, Mirsad Hodi, Hajriz Fejzovi, Zekerija Hajrovi, Zuhdija Hodi, Asim Šairovi, Mersad Plojevi, Murat Muši and Šemsudin Kuevi This document presents additional information and concerns as an update to “The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia - Torture and Unfair Trial of Muslims in the Sandak Region” (AI INDEX: EUR 70/17/95) On 25 March 1996 the Supreme Court of Serbia overturned the verdict of the District Court of Novi Pazar of 12 October 1994 (which had convicted all the above men, Muslims from the Sandak ) and sent the case back for re-trial. At the same time the Supreme Court ordered the release of the six defendants in this trial who had remained in detention (Hajriz Kolašinac, Fadil Ugljanin, Hajro Aljkovi, Demail Etemovi, Šefet Graanin and Nedib Dipko Hodi). Hajriz Kolasinac and his 23 co-defendants were arrested between May and June 1993. On 12 October 1994 they were convicted by the District Court of Novi Pazar of “conspiring to undermine the territorial integrity of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) by the use of violence", under Articles 116 and 136 of the Criminal Code of the FRY. They were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from one to six years. -

Western Balkans at the Crossroads: Ways Forward in Analyzing External Actors’ Influence Edited Volume

WESTERN BALKANS AT THE CROSSROADS: EDITED VOLUME Western Balkans at the Crossroads: Ways Forward in Analyzing External Actors’ Influence Edited Volume Edited by Ioannis Armakolas, Barbora Chrzová, Petr Čermák and Anja Grabovac April 2021 Western Balkans at the Crossroads: Ways Forward in Analyzing External Actors’ Influence Edited Volume Editors: Ioannis Armakolas, Barbora Chrzová, Petr Čermák and Anja Grabovac Authors: Ioannis Armakolas, Maja Bjeloš, Petr Čermák, Barbora Chrzová, Ognjan Denkovski, Stefan Jojić, Srećko Latal, Gentiola Madhi, Martin Naunov, Tena Prelec, Senada Šelo Šabić, Anastas Vangeli, Stefan Vladisavljev Proofreading: Zack Kramer Published by the Prague Security Studies Institute, April 2021, Prague The publication is written within the framework of the project “Western Balkans at the Crossroads: Ways Forward in Analyzing External Actors Influence“ led by the Prague Security Studies Institute with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy. ISBN: 978-80-903792-8-2 © PSSI 2021 The Prague Security Studies Institute, Pohořelec 6 118 00 Prague 1, Czech Republic www.pssi.cz Content About the Project and Authors 5 Introduction 8 Part I — Domestic Narratives on External Actors’ Presences 1. ‘Our Brothers’, ‘Our Saviours’: The Importance of Chinese Investment for the Serbian Government’s Narrative of Economic Rebound 12 Tena Prelec 2. “Steel Friendship” — Forging of the Perception of China by the Serbian Political Elite 23 Stefan Vladisavljev 3. China’s Ideational Impact in the Western Balkans, 2009–2019 39 Anastas Vangeli Part II — Domestic Cleavages and External Actors’ Involvement – An Active or Passive Role? 4. BiH’s Decisive Electoral Reform Strikes New Divisions Among Internal and External Actors 56 Srećko Latal 5. -

10409/98 Thy/PT/Ip EN DG H I 2 You Will Find Below Information on Various Aspects of the Situation in the Sandzak Region, Situat

You will find below information on various aspects of the situation in the Sandzak region, situated in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro; FRY) which is considered to be significant for the assessment of asylum applications and decision-making on the removal of rejected asylum-seekers originating in Sandzak. In drawing up the following report, particular account was taken of the claims made by various asylum-seekers originating in Sandzak in their asylum applications in the past. The information given below is based, inter alia, on our own investigation on the spot. Use has also been made of information from local human rights organisations, Amnesty International, the OSCE, ECMM, UNHCR and other UN organisations, and from various European partners, confirmed press reports, information from the FRY authorities and official documents, letters and communiqués from Muslim organisations such as the SDA and the MNCS. Because of their presumed propagandist content (on the part of both the authorities and the Muslim organisations), "official" documents are used only if the information they contain can be confirmed from other sources. 1. General situation 1.1 Introduction Sandzak (1) is an area situated partly in Montenegro and partly in Serbia, on a high plateau in the centre of the Balkans. The main town, Novi Pazar, is its cultural and economic centre, and the majority of the population are Muslims. The authorities of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro; hereinafter referred to as the "FRY") deny the fact that Sandzak has ever existed as a territorial or administrative unit in Yugoslavia. In the present FRY, as well as in its composite Republics, Sandzak has never been referred to as a distinct unit, and so "Sandzak" does not officially exist.