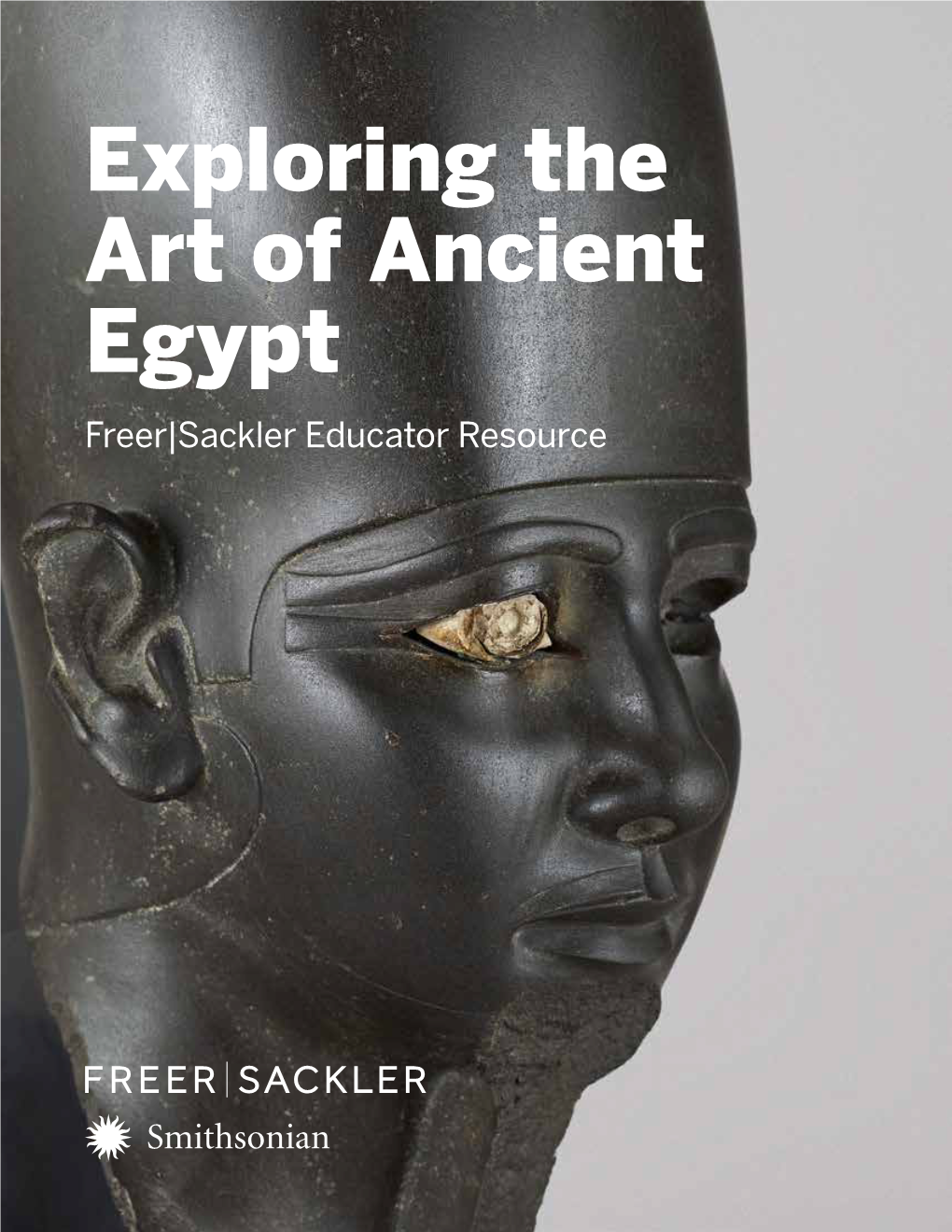

Exploring the Art of Ancient Egypt Freer|Sackler Educator Resource Exploring the Art of Ancient Egypt About This Work of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt and the Egyptians

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61689-8 - Egypt and the Egtptians, Second Edition Douglas J. Brewer and Emily Teeter Frontmatter More information Egypt and the Egyptians Surveying more than three thousand years of Egyptian civilization, Egypt and the Egyptians offers a comprehensive introduction to this most rich and complex of early societies. From high politics to the concerns of everyday Egyptians, the book explores every aspect of Egyptian culture and society, including religion, language, art, architecture, cities, and mummification. Archaeological and doc- umentary sources are combined to give the reader a unique and expansive view of a remarkable ancient culture. Fully revised and updated, this new edition looks more closely at the role of women in Egypt, delves deeper into the Egyptian Neolithic and Egypt’s transi- tion to an agricultural society, and includes many new illustrations. Written for students and the general reader, and including an extensive bibliography, a glossary, a dynastic chronology and suggestions for further reading, this richly illustrated book is an essential resource for anybody wishing to explore the society and civilization of ancient Egypt. douglas j. brewer is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Illi- nois, Urbana, and Director of the Spurlock Museum. He is the author of numer- ous books and articles on Egypt covering topics from domestication to cultural change and the environment. He has over twenty-five years’ experience of field- work in Egypt and is currently co-director of the excavations at Mendes. emily teeter is an Egyptologist and Research Associate at the Oriental Insti- tute, University of Chicago. -

2019-Egypt-Skydive.Pdf

Giza Pyramids Skydive Adventure February 15-19, 2019 “Yesterday we fell over the pyramids of Giza. Today we climbed into the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid. I could not think of any other way on (or above) the earth to experience all of the awe inspiring mysteries that this world has to offer.” JUMP Like a Pharaoh in 2019 Start making plans now for our first Tandem Jump Adventure over the Pyramids of Giza! Tandem Skydive over the Great Giza Pyramid, one of the Seven Ancient Wonders of the World. Leap from an Egyptian military Hercules C-130 and land between the pyramids. No prior skydiving experience is necessary….just bring your sense of adventure! Skydive Egypt – Sample Itinerary February 15th-19th, 2019 Day 1, February 15 – Arrival Arrive in Cairo, Egypt at own expense Met by Incredible Adventures Representative Transfer to Mercure La Sphinx Hotel * Days 2, 3 - February 16 – 17 – Designated Jump Days** Arrive at Drop Zone Review and sign any necessary waivers Group briefing and equipment fitting Review of aircraft safety procedures and features Individual training with assigned tandem master Complete incredible Great Giza Tandem Skydive Day 4 (5) – February 18 (19) Free Day for Sightseeing & Jump Back-Up Day - Depart Egypt Note: Hotel room will be kept until check-out time on the 19th. American clients should plan to depart on an “overnight flight” leaving after midnight on the 18th. * Designated hotel may change, based on availability. Upgrade to the Marriott Mena for an additional fee. ** You’ll be scheduled in advance to tandem jump on Day 2 or 3, with Day 4 serving as a weather back-up day. -

Giza Plateau Mapping Project. Mark Lehner

GIZA PLATEAU MAPPING PROJECT GIZA PLATEAU MAPPING PROJECT Mark Lehner Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) Season 2017: The Old and the New This year AERA team members busied themselves with the old and very new in research. I had the opportunity to return to some of my earliest work at the Sphinx, thanks to a grant from the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) Antiquities Endowment Fund (AEF) for the Sphinx Digital Database. This project will digitize, conserve, and make available as open source the archive from the 1979–1983 ARCE Sphinx Project, for which Dr. James Allen was project director and I was field director. My work at the Sphinx started three years earlier, in 1977, with Dr. Zahi Hawass, so that makes it exactly forty years ago.1 Search for Khufu We launched a new initiative, directed by Mohsen Kamel and Ali Witsell, to explore the older layers of the Heit el-Ghurab (“Wall of the Crow,” HeG) site. In some areas we have seen an older, different layout below what we have so far mapped, which dates to Khafre and Men- kaure. We believe that the older phase settlement and infrastructure, which was razed and rebuilt, served Khufu’s building of the Great Pyramid. The discovery in 2013, and publication this year, of the Journal of Merer2 piques our interest all the more in the early phase of Heit el-Ghurab. Pierre Tallet and a team from the Sorbonne and the French Institute in Cairo discovered the inscribed papyri at Wadi el-Jarf on the west- ern Red Sea Coast, in a port facility used only in the time of Khufu. -

Student Stories on the Great Pyramid of Giza

The Wonder that Will Make You Wonder- The Great Pyramid of Giza by Kenneth Canales 0. The Wonder that Will Make You Wonder- The Great Pyramid of Giza by Kenneth Canales - Story Preface 1. Pyramid of Giza by Rebecca Gauvin and Bailey Cotton 2. Wonderful Wonders - The Pyramids of Giza by Tiffany Rubio 3. The Wonder that Will Make You Wonder- The Great Pyramid of Giza by Kenneth Canales 4. One Of The Seven Wonders Of The World: The Pyramids Of Giza By Dominic Scruggs and Jahziel Baez-Perez 5. The Great Pyramid of Giza by John Paul Jones 6. What a WONDERful World, by Warren Frankos 7. The Mysterious TOMB! By Andre Coteau and Erick Collazo 8. Do You Wonder about the Seven Wonders by Nolan Olson 9. The Pyramids of Egypt by Victor Toalombo Astaiza 10. The Great Pyramids of Giza by Yessibeth Jaimes 11. The Pyramids of Giza, A Wonder Among Many by Lyah S. Mercado 12. The Pyramids of Giza by Kara Rutledge and Aaron Anderson 13. The Great Pyramids of Egypt by Myco Jean-Baptiste and Fox Gregory 14. The Truth Behind The Pyramids of Giza by Kayley Best and Alexis Anstadt 15. The Great Pyramids of Giza by Brooke Massey & Miranda Steele 16. How Great Are The Great Pyramids Of Giza? by Zachariah Bessette and Carmela Burns The Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt is the best wonder of the 7 Wonders of the World and everyone deserves to learn about it. The Great Pyramid of Giza is in Cairo, Egypt. Giza is a city in Cairo. -

Ancient History Notes from the Examination Centre Board of Studies 2000

1999 HSC Ancient History Notes from the Examination Centre Board of Studies 2000 Published by Board of Studies NSW GPO Box 5300 Sydney NSW 2001 Australia Tel: (02) 9367 8111 Fax: (02) 9262 6270 Internet: http://www.boardofstudies.nsw.edu.au April 2000 Schools may reproduce all or part of this document for classroom use only. Anyone wishing to reproduce elements of this document for any other purpose must contact the Copyright Officer, Board of Studies NSW. Ph: (02 9367 8111; fax: (02) 9279 1482. ISBN 0 7313 4473 1 2000184 Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................................................4 2 Unit — Personalities and Their Times ..........................................................................................5 Section I — Ancient Societies .........................................................................................................5 Part A — Egypt .........................................................................................................................5 Part B — Near East....................................................................................................................7 Part C — Greece........................................................................................................................8 Part D — Rome .......................................................................................................................12 Section II — Personalities and Groups ......................................................................................... -

The Birth of Moses

1. THE BIRTH OF MOSES We arrived at Cairo International Airport just after nightfall. Though weary from a day of flying, we were excited to finally set foot on Egyptian soil and to catch a glimpse, by night, of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It took an hour and fifteen minutes to drive from the airport, on the northeast side of Cairo, to Giza, a southern suburb of the city. Even at night the streets were congested with the swelling population of twenty million people who live in greater Cairo. Upon checking into my hotel room, I opened the sliding door to my balcony, and stood for a moment, in awe, as I looked across at the pyramids by night. I was gazing upon the same pyramids that pharaohs, patriarchs, and emperors throughout history had stood before. It was a breathtaking sight. Copyright © by Abingdon21 Press. All rights reserved. 9781501807886_INT_Layout.indd 21 3/10/17 9:00 AM Moses The Pyramids and the Power of the Pharaohs Some mistakenly assume that these pyramids were built by the Israelite slaves whom Moses would lead to freedom, but the pyramids were already ancient when Israel was born. They had been standing for at least a thousand years by the time Moses came on the scene. So, if the Israelites were not involved in the building of these structures, why would we begin our journey—and this book—with the pyramids? One reason is simply that you should never visit Egypt without seeing the pyramids. More importantly, though, we begin with the pyramids because they help us understand the pharaohs and the role they played in Egyptian society. -

Kathryn A. Bard, an Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (Malden, Ma: Blackwell Publishing, 2008). Reviewed by Jeff

Kathryn A. Bard, An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (Malden, Ma: Blackwell Publishing, 2008). Reviewed by Jeff Cutright Jeff ‘s interests include the relationships between the Roman and Parthian Empires and the interactions between an assortment of ancient and early medieval cultures along frontier regions. After completing the M.A. here at EIU, he will attend Louisiana State University to begin work on a Ph.D. in ancient history. In her preface, Kathryn Bard states the impetus for writing this book was that there was “no one text that covered everything … in a comprehensive survey.”389 Attempting to incorporate everything she ever “wanted to know about ancient Egypt” when first beginning her study, Bard’s first three chapters include the background necessary to understand the survey of Egyptian archaeology and history.390 These initial chapters focus on the ecology, geography, and natural resources available in Egypt. The following seven chapters offer a detailed analysis of Egyptian archaeology on a chronological foundation beginning with the Paleolithic, around 500,000 years ago, and extending through the Greco-Roman Period. While textbooks on Egyptian history discuss the archaeology to supplement the history, Bard explicates the history based in, and extracted from, the archaeology of Egypt, not the other way around. Throughout the book, Bard narrates a thoroughly detailed and thoughtful history of Egypt. Bard devotes the final chapter to a summary of the current applications and potential implications of ancient Egyptian archaeology. In keeping with her stated goal of writing a textbook designed for classroom, Bard includes a set of chapter summaries and review questions in the back. -

ARCE Member-Only Tour to Egypt Fall 2019.Pdf

ARCE Member Tour of Egypt October 20- November 3, 2019 Sunday October 20 | Arrive in Cairo Meals Included: Dinner Meet and Greet at Cairo Airport To ensure your journey is seamless from the start, our representative will meet you before passport control to assist with acquiring your visa stamps, moving through passport control, and collecting your luggage. Later you will be transferred to the Cairo Marriott Hotel in Zamalek for check-in Dinner at hotel Overnight in Cairo Monday, October 21 | Pyramids of Giza, Sphinx, Solar Boat, Sakkara Meals Included: Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner 06:30 AM Buffet breakfast at the hotel 07:30 AM Meet your guide and head to the Giza Plateau 08:30 AM Private visit to the Paws of the Sphinx. The Sphinx is the largest monolithic statue in the world and the oldest known monumental sculpture. Proceed to the famous Giza Pyramid Complex. Dominating the plateau and running in a southwest diagonal through the site are the three pyramids of the pharaohs Khufu, Khafra, and Menkaura. The northernmost and the largest belongs to Khufu. Khafra's pyramid is built precisely on a southwest diagonal to his father's pyramid on higher ground to create the illusion of being bigger. The pyramid of Menkaura is much smaller and is not aligned on the same diagonal axis as the other two pyramids. Entry to the Great Pyramid of Khufu and Solar Boat Museum are included. - Lecture by Dr. Zahi Hawass & Mark Lehner at the Paws of the Sphinx Visit to the Conservation Center at the Grand Egyptian Museum Lunch at Sakkara Palm Club Then to Sakkara, the ancient burial site considered by many archaeologists to be home to some of the world's most important excavations. -

2020 Member to Egypt Itinerary 0.Pdf

ARCE Member Tour of Egypt November 05 – 22, 2020 Thursday, November 05| Arrive in Cairo. Meals Included: Dinner. Meet and Greet at Cairo Airport To ensure your journey is seamless from the start, our representative will meet you before passport control to assist with acquiring your visa stamps, move through passport control, and collect your luggage. Later you will be transferred to the Nile Ritz Carlton Hotel for check-in. Dinner at hotel. Overnight in Cairo. Friday, November 06| Sakkara / Coptic Cairo / Coptic Museum. Meals Included: Breakfast / Lunch / Dinner. 07:00 Buffet breakfast at hotel. 08:00 Meet your guide at the lobby and head to Sakkara, site of the Step Pyramid of King Djoser was constructed by Imhotep in the Third Dynasty. The pyramid is part of the tomb complex of Djoser, the first Pharaoh of the Old Kingdom. The pyramid began as a simple Mastaba, or long, flat tomb building and was the first construction to be built from stone. Visit to the Serapeum included. Noon Lunch at Sakkara Palm Club. After lunch, head to Coptic Cairo, were you will visit the Hanging Church, which dates back to the late 4th and early 5th century. This basilica was named "Al-Mu'allaqah," meaning “The Suspended Poems,” because it was built on top of the south gate of the Fortress of Babylon. Then to the Church of St. Sergius, which dates to the beginning of the 5th century. This basilica is built on the cave in which the Holy Family stayed and is regarded by some as a source of blessing. -

Giza Planetary Alignment

GIZA PLANETARY ALIGNMENT MYSTERIES OF THE PYRAMID CLOCK ANNOUNCING A NEW TIME The purpose of this illustration is to address some misconceptions about the Dec 3, 2012 Planetary Alignment of Mercury, Venus and Saturn. The error is that the planets are alleged to be in direct line with the Giza Pyramids and visible after sunset as one would look toward the west from the Pyramid complex. A picture of the Planets above the Giza Pyramid complex in Egypt has been online for a while but it is not exactly what will occur. This study will examine if such a scenario is possible altogether. Since the Pyramids are at the center piece of this planetary alignment, some investigations associated with the Pyramids will be looked at to further appreciate the complexity of such magnificent structures. It does appear that the planetary alignment of Mercury, Venus and Saturn, by themselves will have on Dec 3, 2012, the same degree of angle as the Giza Pyramid complex. Thus it will also mirror the degree of angel to that of Orion’s Belt –which the Pyramids are designed after. A timeline will show various day count or number pattern associated with prior astronomical events. (7 cycles of 7 Day intervals) NOV 6 NOV 13/14 NOV 19 NOV 21 NOV 28/29 DEC 3 DEC 7/8 DEC 21 DEC 31/1 Gaza-Israel = 49 Days, JAN 1 = 50th OCT 29/30 USA Elections Total Solar Eclipse Solar Flare Partial Lunar Eclipse Alignment Hanukah Winter Solstice USA ‘Fiscal Cliff’ Obama Reelected Cease Fire from Solar Eclipse Hurricane Sandy midst of Eclipses Operation Pillar of Cloud 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 Day Conflict 7 Days to Lunar Eclipse 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 N O V E M B E R D E C E M B E R 9 D A Y S 9 D A Y S 9 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 7 D A Y S 9 D A Y S ‘9-9-9’ After the 7779 pattern, a 999 or 666 follows up to Christmas. -

Building the Great Pyramid at Giza: Investigating Ramp Models Jennifer (Kali) Rigby Brown University

Rigby 1 Building The Great Pyramid At Giza: Investigating Ramp Models Jennifer (Kali) Rigby Brown University Rigby 2 “If the [internal ramp] theory is correct, it gives us a window into one of the greatest intellectual achievements of all time; it shows us just how advanced ancient Egyptian architects were in planning the pyramids, how far ahead they had to visualize to overcome incredible obstacles. Indeed, if Jean-Pierre is right about the details of construction, the Pyramid might just be the most extraordinary engineering accomplishment of all time, a monument in stone to what the human mind at its best is capable of.” Bob Brier, The Secret of the Great Pyramid (21) Abstract How were the ancient Egyptians able to move 2.5-ton blocks to build the Great Pyramid without today’s machinery? Khufu’s Pyramid at Giza was a massive undertaking, requiring approximately two million stone blocks weighing an average of 2.5 tons to be set into place, five every minute during the first years of construction (Romer 2007, 197). Without any records on the construction of this ancient wonder, scholars have proposed various theories on how the Great Pyramid was built. Many scholars believe that the ancient Figure 1: The Great Pyramid At Giza (Khufu’s Egyptians created ramps beside the Pyramid) pyramids to transport the blocks to each new level, but even they are not completely convinced by the proposed models, the most prominent being the long ramp and the spiral ramp models. Over the last fifteen years, the French architect Jean-Pierre Houdin has developed a new theory, one of an internal spiral ramp that was covered upon the Pyramid’s completion, which may solve this thousands’ year old mystery. -

Patterns of the Pyramids

FORTRESSES OF THE MARTIAN GODS PATTERNS OF THE PYRA MIDS The purpose of this study is to illustration that the Giza Pyramid complex of Egypt on Earth not only incorporates the Belt of Orion star constellation corresponding to the 3 main pyramids but that the pyramid complex also has an encrypted pattern of the Pleiades in similar parallel proportion. This assertion and clued is taken from the Pleiadian pattern that is found on Mar’s Pyramid City of Cydonia. The key to linking both pyramid complexes is the pentagon that is at the core each complex. There is a 1 for 1 match in orientation. Amazing this Pleiades pattern on Mars also approximates the angles and proportion on Earth. The illustration will show the 2 pyramid cities and the corresponding ley-lines for a visual match. Not surprisingly the Giza Pyramid complex just outside Cairo that is corresponding to the Cydonia, Mars pyramid complex has the root word with connotations to Mars. It is understood that at the time of the founding of the city of Cairo, the rising of Mars was taking place. Some unique observations about the mutual correspondence involving the Pleiades star cluster and Orion constellation are as follows. The approximate matching of the 2 pyramid complexes occurs as the Giza composition is inverted horizontally and flipped at a 90 degree angle. Normally the Great Pyramid is aligned to true north. This is exactly how the Pyramid City of Cydonia, Mars is also aligned to true north on Mars. Subsequently the composition of the Giza Pyramids involves an amazing array of mathematics, sacred As noted, this geometric pentagram is also Gematria and esoteric composition.