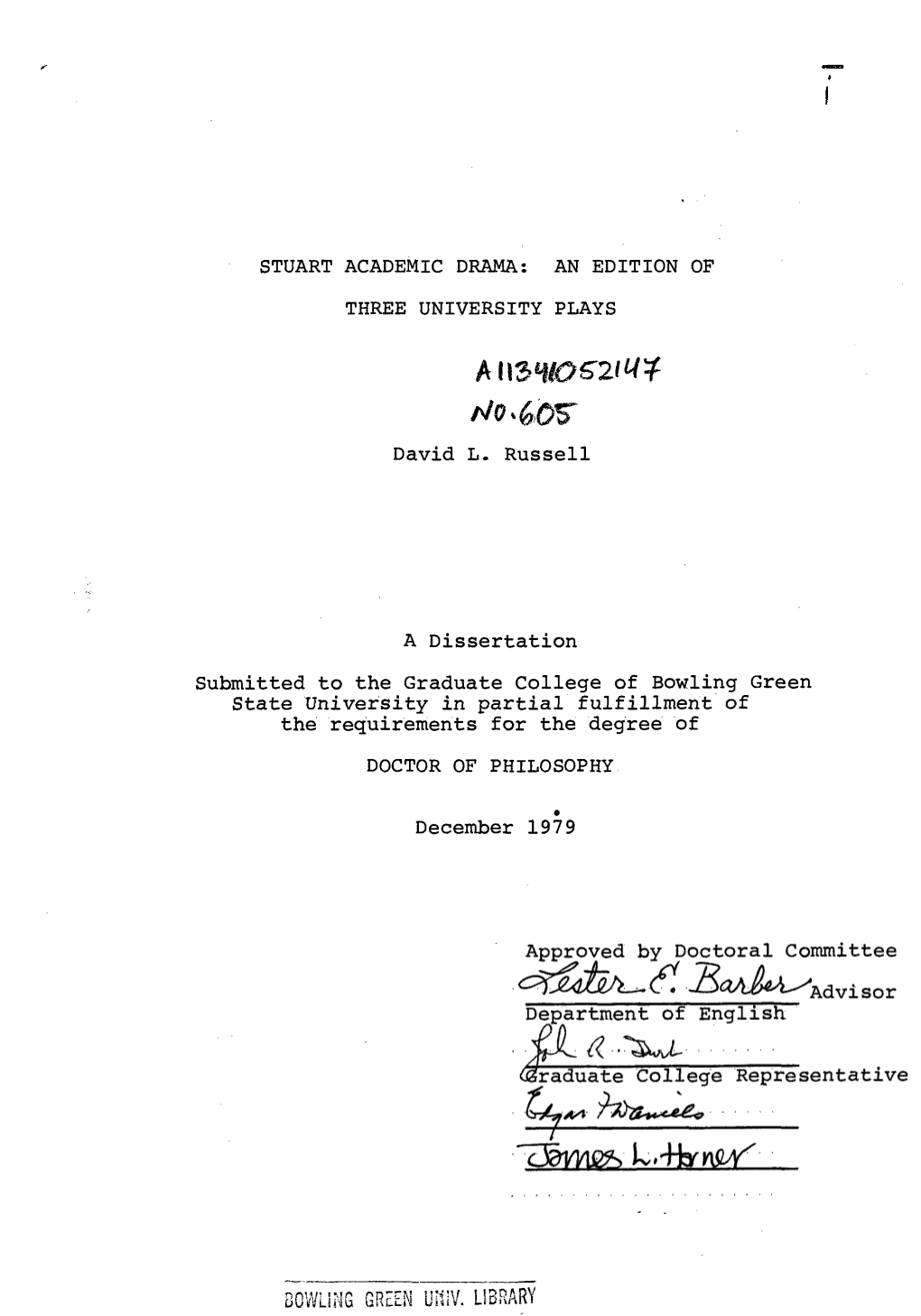

Stuart Academic Drama: an Edition Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W. Griffith, BROKEN BLOSSOMS, OR THE YELLOW MAN AND THE GIRL (1919, 90 minutes) Directed, written and produced by D.W. Griffith Based on a story by Thomas Burke Cinematography by G.W. Bitzer Film Editing by James Smith Lillian Gish ... Lucy - The Girl Richard Barthelmess ... The Yellow Man Donald Crisp ... Battling Burrows D.W. Griffith (director) (b. David Llewelyn Wark Griffith, January 22, 1875 in LaGrange, Kentucky—d. July 23, 1948 (age 73) in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California) won an Honorary Academy Award in 1936. He has 520 director credits, the first of which was a short, The Adventures of Dollie, in 1908, and the last of which was The Struggle in 1931. Some of his other films are 1930 Abraham Lincoln, 1929 Lady of the Pavements, 1928 The Battle of the Sexes, 1928 Drums of Love, 1926 The Sorrows of Satan, 1925 That Royle Girl, 1925 Sally of the Sawdust, 1924 Darkened Vales (Short), 1911 The Squaw's Love (Short), 1911 Isn't Life Wonderful, 1924 America, 1923 The White Rose, 1921 Bobby, the Coward (Short), 1911 The Primal Call (Short), 1911 Orphans of the Storm, 1920 Way Down East, 1920 The Love Enoch Arden: Part II (Short), and 1911 Enoch Arden: Part I Flower, 1920 The Idol Dancer, 1919 The Greatest Question, (Short). 1919 Scarlet Days, 1919 The Mother and the Law, 1919 The Fall In 1908, his first year as a director, he did 49 films, of Babylon, 1919 Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the some of which were 1908 The Feud and the Turkey (Short), 1908 Girl, 1918 The Greatest Thing in Life, 1918 Hearts of the World, A Woman's Way (Short), 1908 The Ingrate (Short), 1908 The 1916 Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages, 1915 Taming of the Shrew (Short), 1908 The Call of the Wild (Short), The Birth of a Nation, 1914 The Escape, 1914 Home, Sweet 1908 Romance of a Jewess (Short), 1908 The Planter's Wife Home, 1914 The Massacre (Short), 1913 The Mistake (Short), (Short), 1908 The Vaquero's Vow (Short), 1908 Ingomar, the and 1912 Grannie. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Gown Before Crown: Scholarly Abjection and Academic Entertainment Under Queen Elizabeth I Linda Shenk Iowa State University, [email protected]

English Publications English 2009 Gown Before Crown: Scholarly Abjection and Academic Entertainment Under Queen Elizabeth I Linda Shenk Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/engl_pubs Part of the European History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, and the Women's History Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ engl_pubs/142. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gown Before Crown: Scholarly Abjection and Academic Entertainment Under Queen Elizabeth I Abstract In 1592, Queen Elizabeth I and the Privy Council made a rather audacious request of their intellectuals at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The hrC istmas season was fast approaching, and a recent outbreak of the plague prohibited the queen's professional acting company from performing the season's customary entertainment. To avoid having a Christmas without revels, the crown sent messengers to both institutions, asking for university men to come to court and perform a comedy in English. Cambridge's Vice Chancellor, John Still, wished to decline this royal invitation, and for advice on how to do so he wrote to his superior, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who was not only the Chancellor of Cambridge but also Elizabeth's chief advisor. -

The Pedimental Sculpture of the Hephaisteion

THE PEDIMENTALSCULPTURE OF THE HEPHAISTEION (PLATES 48-64) INTRODUCTION T HE TEMPLE of Hephaistos, although the best-preserved ancient building in Athens and the one most accessible to scholars, has kept its secrets longer than any other. It is barely ten years since general agreement was reached on the name of the presiding deity. Only in 1939 was the evidence discovered for the restora- tion of an interior colonnade whicli at once tremendously enriched our conception of the temple. Not until the appearance of Dinsmoor's study in 1941 did we have a firm basis for assessing either its relative or absolute chronology.' The most persistent major uncertainty about the temple has concerned its pedi- mental sculpture. Almost two centuries ago (1751-55), James Stuart had inferred 1 The general bibliography on the Hephaisteion was conveniently assembled by Dinsmoor in Hesperia, Supplement V, Observations on the Hephaisteion, pp. 1 f., and the references to the sculpture loc. cit., pp. 150 f. On the sculpture add Olsen, A.J.A., XLII, 1938, pp. 276-287 and Picard, Mamtel d'Archeologie grecque, La Sculpture, II, 1939, pp. 714-732. The article by Giorgio Gullini, " L'Hephaisteion di Atene" (Archeologia Classica, Rivista dell'Istituto di Archeologia della Universita di Roma, I, 1949, pp. 11-38), came into my hands after my MS had gone to press. I note many points of difference in our interpretation of the sculptural history of the temple, but I find no reason to alter the views recorded below. Two points of fact in Gullini's article do, however, call for comment. -

Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy the Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of Its Impending End

Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy The Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of its Impending End A doctoral thesis by O. H. Linderborg Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Engelska Parken, 7-0042, Thunbergsvägen 3H, Uppsala, Monday, 3 September 2018 at 14:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Docent Elton Barker (Open University). Abstract Linderborg, O. H. 2018. Herodotus and the Origins of Political Philosophy. The Beginnings of Western Thought from the Viewpoint of its Impending End. 224 pp. Uppsala: Department of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2703-9. This investigation proposes a historical theory of the origins of political philosophy. It is assumed that political philosophy was made possible by a new form of political thinking commencing with the inauguration of the first direct democracies in Ancient Greece. The pristine turn from elite rule to rule of the people – or to δημοκρατία, a term coined after the event – brought with it the first ever political theory, wherein fundamentally different societal orders, or different principles of societal rule, could be argumentatively compared. The inauguration of this alternative-envisioning “secular” political theory is equaled with the beginnings of classical political theory and explained as the outcome of the conjoining of a new form of constitutionalized political thought (cratistic thinking) and a new emphasis brought to the inner consistency of normative reasoning (‘internal critique’). The original form of political philosophy, Classical Political Philosophy, originated when a political thought launched, wherein non-divinely sanctioned visions of transcendence of the prevailing rule, as well as of the full range of alternatives disclosed by Classical Political Theory, first began to be envisioned. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Or, Instructions How to Play at Billiards, Trucks, Bowls, and Chess, 2Nd Ed

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1680 The compleat gamester : or, instructions how to play at billiards, trucks, bowls, and chess, 2nd ed. Printed for Henry Brome http://hdl.handle.net/1880/547 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca 'r-SSSBseflB ^ wCOMPL^ v'. -"^^arrr-Fs^Y AT^ *;i?l *i;v •tfi -OR,' •"-..•; INSTRUCTIONS How to play at BlLLURDSiffltCKS, BOWLS, **d CHESS. Together with-all dinner of ufual tod moft Gentile GAM u s either GO • ' or To which' is Added, P F RACING, COCK-RGHTING. •-# T, Primed for Htwy Brtmt i» the Weft-end of St. P**lf> -, 1 *••'.'' v, to *; > f. VVa& oncc rcfoIvS to have let this enfuirafr J 1 ^j • •eatife to have ftcpt naktd ?' into the World, without fo • <>. * much as the leaft rag of an - *• i Epiftle to defend it a little from the cold welconi it may meet with in its travails; but knowing that not only 01^ ftom expeifls but neccffity requires it, give me leave to fhow you the motives indu- cing to thisf prefent public*^ tion. It .is not (He affure you) any private intereft of my own that caus'd me to ad- A 4 ven- >""""""•'•. ~ • , -"-- - - T-T ryqp The Epiftle to the Header. *The Sfijlte to the Header. venture on this fubjec\ but other he would unbend his the delight &; benefit of eve- mind, and give it liberty to ry individual perfon^Delight ftray into fome more pleafant 7 ^ I to fuqh who will pafs away walks, than the rmry heavy their fpare minuts in harmlefs ways of his ownfowr, will* recreation if not abus'd ? and ful refolutions. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

Programma – IPER

PRO GRAMMA 21-22-23 MAG GIO IL PROGRAMMA POTREBBE SUBIRE INTEGRAZIONI E VARIAZIONI PROGRAMMA VENERDÌ 21 MAGGIO Canale #1 Iper Spazio 10:00 GIORGIO DE FINIS / Direttore Museo delle periferie #video IPER Presentazione del Festival delle periferie e saluti istituzionali. 10:30 Politiche per le periferie #pensareurbano La riflessione politica di chi amministra la città, un approfondimento sugli interventi di riqualifi- cazione, di rigenerazione urbana e di riduzione del disagio attuati o in programma per le peri- ferie della città di Roma. Tutti coloro che occupano un ruolo istituzionale sia al livello di Roma Capitale sia dei singoli Municipi sono invitati a prendere la parola a turno. 10:30 VIRGINIA RAGGI / Sindaca 11:00 LORENZA FRUCI / Assessora alla Crescita Culturale 11:30 LUCA MONTUORI / Assessore all’Urbanistica 12:00 MUNICIPIO IV ROBERTA DELLA CASA / Collaboratrice delegata della Sindaca 12:20 MUNICIPIO V GIOVANNI BOCCUZZI / Presidente MARIO PODESCHI / Vicepresidente e Assessore politiche sociali e dei servizi alla persona, politiche di igiene e della promozione della salute, politiche per l’integrazione delle etnie, politiche abitative 13:00 MUNICIPIO VI ROBERTO ROMANELLA / Presidente ALESSANDRO MARCO GISONDA / Vicepresidente e Assessore Politiche della Scuola, Sport, Cultura, Politiche Giovanili, Turismo e Beni Archeologici SERGIO NICASTRO / Assessore Politiche dell’Urbanistica, Lavori Pubblici, ERP, Mobilità 14:00 ON #dis/accordi Necessariamente solo ora e qui, insieme. Per la prima volta, RICCARDO SINIGALLIA (sintetizzatori), ADRIANO VITERBINI (guitar- synth + nguni), ICE ONE (campionatori) danno vita ad un esperimento di vibrazione collettiva basato sull’improvisazione pura, l’empatia, la partecipazione fisica, simultanea, non ripetibile. Una performance lunga tre giorni, tra il concerto e il rituale, che accompagna tutti gli appunta- menti della Sala IPER SPAZIO, per deflagrare in alcuni momenti mai virtuosistici, alla ricerca di un’interazione profonda tra i musicisti e il pubblico collegato e in presenza. -

Twins in Early Modern English Drama and Shakespeare

Downloaded by [New York University] at 04:46 12 April 2017 Twins in Early Modern English Drama and Shakespeare This volume investigates the early modern understanding of twinship through new readings of plays, informed by discussions of twins appear- ing in such literature as anatomy tracts, midwifery manuals, monstrous birth broadsides, and chapbooks. The book contextualizes such dramatic representations of twinship, investigating contemporary discussions about twins in medical and popular literature and how such dialogues resonate with the twin characters appearing on the early modern stage. Murray demonstrates that, in this period, twin births were viewed as biologically aberrant and, because of this classification, authors frequently attempted to explain the phenomenon in ways that call into question the moral and constitutional standing of both the parents and the twins themselves. In line with current critical studies on pregnancy and the female body, discussions of twin births reveal a distrust of the mother and the processes surrounding twin conception; however, a correspond- ing suspicion of twins also emerges, which monstrous birth pamphlets exemplify. This book analyzes the representation of twins in early mod- ern drama in light of this information, moving from tragedies through to comedies. This progression demonstrates how the dramatic potential inherent in the early modern understanding of twinship is capitalized on by playwrights, as negative ideas about twins can be seen transitioning into tragic and tragicomic depictions of twinship. However, by building toward a positive, comic representation of twins, the work additionally suggests an alternate interpretation of twinship in this period, which appreciates and celebrates twins because of their difference. -

D. W. Griffith Centennial

H the Museum of Modern Art U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modemart D.W. GRIFFITH CENTENNIAL Part II, The Feature Films, May 15 to July 9, 1975 Thursday, May 15 5:30 HOME, SWEET HOME. 1914. With Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Blanche Sweet. ca 95 min. and THE MASSACRE. 1912. With Blanche Sweet, ca 30 min. 8:00 D. W. Griffith's THE BIRTH OF A NATION: Muckraking a Southern Legend, a lecture by Russell Merritt, Associate Professor of Communication Arts, University of Wisconsin at Madison Friday, May 16 2:00 THE BIRTH-OF A NATION. 1915. With Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Henry B. Walthall, ca 200 min. Saturday, May 17 3:00 HOME, SWEET HOME and THE MASSACRE. (See Thursday, May 15 at 5:30) 5:30 THE AVENGING CONSCIENCE. 1914. With Henry B. Walthall, Blanche Sweet. ca 95 min. and EDGAR ALLAN POE. 1909. With Herbert Yost, Linda Arvidson. ca 15 min. Sunday, May 18 5:30 THE MOTHER AND THE LAW. 1914-1919. With Mae Marsh, Robert Harron, Miriam Cooper, ca 115 min. Monday, May 19 2:00 THE MOTHER AND THE LAW. (See Sunday, May 18 at 5:30) 5:30 THE BIRTH OF A NATION. (See Friday, May 16 at 2:00) Tuesday, May 20 5:30 THE AVENGING CONSCIENCE and EDGAR ALLAN POE. (See Saturday, May 17 at 5:30) Thursday, May 22 67315 INTOLERANCE. 1916. With Mae Marsh, Robert Harron, Miriam Cooper, ca 195 min. Friday, May 23 2:00 INTOLERANCE. (See Thursday, May 22 at 6:30) Saturday, May 24 3700 A ROMANCE OF HAPPY VALLEY. -

The Subjectivity of Revenge: Senecan Drama and the Discovery of the Tragic in Kyd and Shakespeare

THE SUBJECTIVITY OF REVENGE: SENECAN DRAMA AND THE DISCOVERY OF THE TRAGIC IN KYD AND SHAKESPEARE JORDICORAL D.PHIL THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE SEPTEMBER 2001 But all the time life, always one and the same, always incomprehensibly keeping its identity, fills the universe and is renewed at every moment in innumerable combinations and metamorphoses. You are anxious about whether you will rise from the dead or not, but you have risen already - you rose from the dead when you were born and you didn't notice it. Will you feel pain? Do the tissues feel their disintegration? In other words, what will happen to your consciousness. But what is consciousness? Let's see. To try consciously to go to sleep is a sure way of having insomnia, to try to be conscious of one's own digestion is a sure way to upset the stomach. Consciousness is a poison when we apply it to ourselves. Consciousness is a beam of light directed outwards, it lights up the way ahead of us so that we do not trip up. It's like the head-lamps on a railway engine - if you turned the beam inwards there would be a catastrophe. 'So what will happen to your consciousness? Your consciousness, yours, not anybody else's. Well, what are you? That's the crux of the matter. Let's try to find out. What is it about you that you have always known as yourself? What are you conscious of in yourself? Your kidneys? Your liver? Your blood vessels? - No.