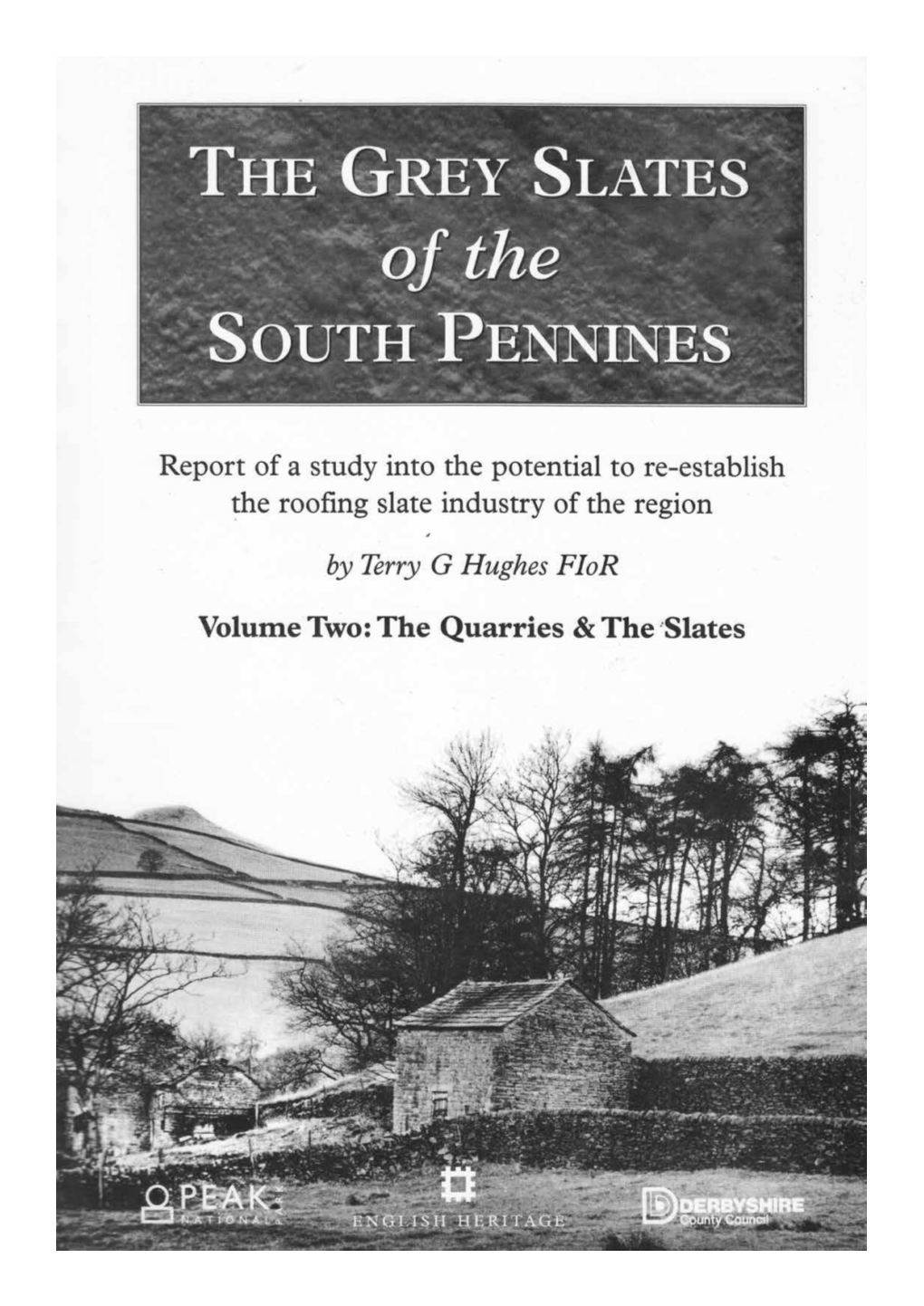

Grey Slate 2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW

2 Fiddlers Mews Fiddlers Bridge | Main Road | Eyam | Derbyshire | S32 5QW 2 FIDDLERS MEWS.indd 1 01/07/2019 14:13 Seller Insight This welcoming family home sits within the beautiful, picturesque village of Eyam in the Peak District,” say the vendors of 2 Fiddlers Mews, “with excellent local cafes and pubs. Eyam is the perfect place for long summer walks through the countryside and is a highly desirable village to live in. The village has great public transport links, with a bus stop right outside the front door, that can get you to all the surrounding villages as well as Sheffield and Chesterfield, making this the perfect property for commuting to work.” Meanwhile, the 3 bedroom mews house lends itself to everyday family life and entertaining alike, with different spaces serving a variety of needs and occasions. “A lovely dining room, with views across the rolling countryside is perfect for entertaining guests and family,” say the vendors. “The dining area leads through double doors to the cosy living room which is perfect for an after dinner coffee. The courtyard provides ample parking for guests, so entertaining is always hassle free.” The outside space also has much to offer, making the most of summer sunshine and enjoying marvellous views. “The property has a gorgeous south facing garden that benefits from the warm afternoon sun,” say the vendors, “so is perfect for enjoying those long summer evenings. The garden also features a patio area with a sun awning to provide shade from the midday heat.” “With its spacious dining room making the most of spectacular countryside views, and a cosy living ideal for after dinner drinks, the property is just as suited to relaxed entertaining as it is to everyday family life.” “I will miss waking up to the beautiful views and being able to walk in the countryside practically outside of the front door. -

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford

The JESSOP Consultancy Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford Document no.: Ref: TJC2020.160 HERITAGE STATEMENT December 2020 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Sir William Hill Road, Eyam, Derbyshire INTRODUCTION SCOPE DESIGNATIONS This document presents a heritage statement for the The building is not statutorily designated. buildings at the former Newfoundland Nursery, Sir There are a number of designated heritage assets William Hill Road, Grindleford, Derbyshire (Figure 1), between 500m and 1km of the site (Figure 1), National Grid Reference: SK 23215 78266. including Grindleford Conservation Area to the The assessment has been informed through a site south-east; a series of Scheduled cairns and stone visit, review of data from the Derbyshire Historic circles on Eyam Moor to the north-west, and a Environment Record and consultation of sources of collection of Grade II Listed Buildings at Cherry information listed in the bibliography. It has been Cottage to the north. undertaken in accordance with guidance published by The site lies within the Peak District National Park. Historic England, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists and Peak District National Park Authority as set out in the Supporting Material section. The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy The JESSOP Consultancy Cedar House Unit 18B, Cobbett Road The Old Tannery 38 Trap Lane Zone 1 Business Park Hensington Road Sheffield Burntwood Woodstock South Yorkshire Staffordshire Oxfordshire S11 7RD WS7 3GL OX20 1JL Tel: 0114 287 0323 Tel: 01543 479 226 Tel: 01865 364 543 NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 Figure 1: Site location plan showing heritage designations The JESSOP Consultancy 2 Sheffield + Lichfield + Oxford NEWFOUNDLAND NURSERY, Eyam, Derbyshire Heritage Statement - Report Ref: TJC2019.158 SITE SUMMARY ARRANGEMENT The topography of the site falls steadily towards the east, with the buildings situated at around c.300m The site comprises a small group of buildings above Ordnance datum. -

State of Nature in the Peak District What We Know About the Key Habitats and Species of the Peak District

Nature Peak District State of Nature in the Peak District What we know about the key habitats and species of the Peak District Penny Anderson 2016 On behalf of the Local Nature Partnership Contents 1.1 The background .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 The need for a State of Nature Report in the Peak District ............................................................ 6 1.3 Data used ........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 The knowledge gaps ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Background to nature in the Peak District....................................................................................... 8 1.6 Habitats in the Peak District .......................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Outline of the report ...................................................................................................................... 12 2 Moorlands .............................................................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Key points ..................................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Nature and value .......................................................................................................................... -

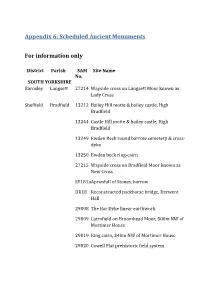

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley

High Peak and Hope Valley January – April 2020 Community Rail Partnership Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley Welcome to this guide It contains details of Guided Walks and Folk Trains on the Hope Valley, Buxton and Glossop railway lines. These railway lines give easy access to the beautiful Peak District. Whether you fancy a great escape to the hills, or a night of musical entertainment, let the train take the strain so you can concentrate on enjoying yourself. High Peak and Hope Valley This leaflet is produced by the High Peak and Hope Valley Community Rail Partnership. Community Rail Partnership Telephone: 01629 538093 Email: [email protected] Telephone bookings for guided walks: 07590 839421 Line Information The Hope Valley Line The Buxton Line The Glossop Line Station to Station Guided Walks These Station to Station Guided Walks are organised by a non-profit group called Transpeak Walks. Everyone is welcome to join these walks. Please check out which walks are most suitable for you. Under 16s must be accompanied by an adult. It is essential to have strong footwear, appropriate clothing, and a packed lunch. Dogs on a short leash are allowed at the discretion of the walk leader. Please book your place well in advance. All walks are subject to change. Please check nearer the date. For each Saturday walk, bookings must be made by 12:00 midday on the Friday before. For more information or to book, please call 07590 839421 or book online at: www.transpeakwalks.co.uk/p/book.html Grades of walk There are three grades of walk to suit different levels of fitness: Easy Walks Are designed for families and the occasional countryside walker. -

REPORT for 1956 the PEAK DISTRICT & NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY- 1956

THE PEAK DISTRICT AND NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY 1 8 9 4 -- 1 9 56 Annual REPORT for 1956 THE PEAK DISTRICT & NORTHERN COUNTIES FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY- 1956 President : F . S. H. Hea<l, B.sc., PB.D. Vice-Presidents: Rt. Hon. The Lord Chorley F. Howard P. Dalcy A. I . Moon, B.A. (Cantab.) Council: Elected M embers: Chairman: T. B'oulger. Vice-Chairman: E. E. Ambler. L. L. Ardern J. Clarke L. G. Meadowcrort Dr. A. J. Bateman Miss M. Fletcher K. Mayall A. Ba:es G. R. Estill A. Milner D .T. Berwick A. W. Hewitt E. E. Stubbs J. E. Broom J. H. Holness R. T. Watson J. W. Burterworth J. E. l\lasscy H. E. Wild Delegates from Affiliated Clubs and Societies: F. Arrundale F. Goff H. Mills R. Aubry L. G riffiths L. Nathan, F.R.E.S. E .BaileY. J. Ha rrison J. R. Oweo I . G. Baker H. Harrison I. Pye J. D. Bettencourt. J. F. Hibbcrt H. Saodlcr A.R.P.S. A. Hodkinson J. Shevelan Miss D. Bl akeman W. Howarth Miss L. Smith R. Bridge W. B. Howie N. Smith T. Burke E. Huddy Miss M. Stott E. P. Campbell R. Ingle L. Stubbs R. Cartin L. Jones C. Taylor H. W. Cavill Miss M. G. Joocs H. F. Taylor J . Chadwick R. J. Kahla Mrs. W. Taylor F. J. Crangle T. H. Lancashire W. Taylor Miss F. Daly A. Lappcr P. B. Walker M:ss E. Davies DJ. Lee H. Walton W. Eastwood W. Marcroft G. H. -

A Survey of Building Stone and Roofing Slate in Falkirk Town Centre

A survey of building stone and roofing slate in Falkirk town centre Minerals & Waste Programme Open Report OR/13/015 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS & WASTE PROGRAMME OPEN REPORT OR/13/015 A survey of building stone and roofing slate in Falkirk town The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown centre Copyright and database rights 2013. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290. M R Gillespie, P A Everett, L J Albornoz-Parra and E A Tracey Keywords Falkirk, building stone, roofing slate, survey, quarries, stone- matching. Front cover The Steeple, Falkirk town centre. Original early 19th Century masonry of local Falkirk sandstone at middle levels. Lower levels clad in buff sandstone from northern England in late 20th Century. Spire reconstructed in unidentified th sandstone in early 20 Century. Bibliographical reference GILLESPIE, M R, EVERETT, P A, ALBORNOZ-PARRA, L J and TRACEY, E A. 2013. A survey of building stone and roofing slate in Falkirk town centre. British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/13/015. 163pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. © NERC 2013. -

THE STATUS of GOLDEN PLOVERS in the PEAK PARK, ENGLAND in RELATION to ACCESS and RECREATIONAL DISTURBANCE by D.W.Yalden

3d THE STATUS OF GOLDEN PLOVERS IN THE PEAK PARK, ENGLAND IN RELATION TO ACCESS AND RECREATIONAL DISTURBANCE by D.W.Yalden A survey of all Peak Park moorlands in 1970-75 concerned birds which had moved onto the then located approximately 580-d00 pairs of Golden recent fire site of Totside Moss - I recorded Plovers (P•u•$ •pr•c•r•); on the present only 2 pairs in those 1-km squares, where they county boundaries around half of these are in found 11 pairs. Also the S.E. Cheshire Derbyshire, a few in Cheshire, Staffordshire moorlands have recently been thoroughly studied and Lancashire (16, 6 and 2 pairs, during the preparation of a breeding bird atlas respectively), and the rest in Yorkshire for the county. Where I found 15 pairs in (Yalden 1974). There are very sparse 1970-75, there seem to be only eight pairs now populations of Golden Plovers in S.W. Britain (A. Booth, D.W. Yalden pets. ohs.). and Wales. On Dartmoor, an R.S.P.B. survey found only 14 pairs, and in the national The Pennine Way long distance footpath runs breeding bird survey this species was only along the ridge from Snake Summit south to recorded in 50 (10 km) squares in Wales, (Mudge Mill-Hill and consequently this area has been et a•. 1981, Shatrock 1976): the total Welsh subjected to disturbance from hill-walkers. population was estimated at 600 pairs. Further Here the Golden Plover population has been north in the Pennines, and in Scotland, tensused annually since 1972. The population populations are larger. -

Places to See and Visit

Places to See and Visit When first prepared in 1995 I had prepared these notes for our cottages one mile down the road near Biggin Dale with the intention of providing information regarding local walks and cycle rides but has now expanded into advising as to my personal view of places to observe or visit, most of the places mentioned being within a 25 minutes drive. Just up the road is Heathcote Mere, at which it is well worth stopping briefly as you drive past. Turn right as you come out of the cottage, right up the steep hill, go past the Youth Hostel and it is at the cross-road. In summer people often stop to have picnics here and it is quite colourful in the months of June and July This Mere has existed since at least 1462. For many of the years since 1995, there have been pairs of coots living in the mere's vicinity. If you turn right at the cross roads and Mere, you are heading to Biggin, but after only a few hundred yards where the roads is at its lowest point you pass the entrance gate to the NT nature reserve known as Biggin Dale. On the picture of this dale you will see Cotterill Farm where we lived for 22 years until 2016. The walk through this dale, which is a nature reserve, heads after a 25/30 minute walk to the River Dove (There is also a right turn after 10 minutes to proceed along a bridleway initially – past a wonderful hipped roofed barn, i.e with a roof vaguely pyramid shaped - and then the quietest possible county lane back to Hartington). -

Parish Council Guide for Residents

CHAPEL-EN-LE-FRITH PARISH WELCOME PACK TITLE www.chapel-en-le-frithparishcouncil.gov.uk PARISH COUNCILGUIDE FOR RESIDENTS Contents Introduction The Story of Chapel-en-le-Frith 1 - 2 Local MP, County & Villages & Hamlets in the Parish 3 Borough Councillors 14 Lots to Do and See 4-5 Parish Councillors 15 Annual Events 6-7 Town Hall 16 Eating Out 8 Thinking of Starting a Business 17 Town Facilities 9-11 Chapel-en-le-Frith Street Map 18 Community Groups 12 - 13 Village and Hamlet Street Maps 19 - 20 Public Transport 13 Notes CHAPEL-EN-LE-FRITH PARISH WELCOME PACK INTRODUCTION Dear Resident or Future Resident, welcome to the Parish of Chapel-en-le-Frith. In this pack you should find sufficient information to enable you to settle into the area, find out about the facilities on offer, and details of many of the clubs and societies. If specific information about your particular interest or need is not shown, then pop into the Town Hall Information Point and ask there. If they don't know the answer, they usually know someone who does! The Parish Council produces a quarterly Newsletter which is available from the Town Hall or the Post Office. Chapel is a small friendly town with a long history, in a beautiful location, almost surrounded by the Peak District National Park. It's about 800 feet above sea level, and its neighbour, Dove Holes, is about 1000 feet above, so while the weather can be sometimes wild, on good days its situation is magnificent. The Parish Council takes pride in maintaining the facilities it directly controls, and ensures that as far as possible, the other Councils who provide many of the local services - High Peak Borough Council (HPBC) and Derbyshire County Council (DCC) also serve the area well. -

Moorland Marathons Philip Brockbank 71

( ~~~~~~-T-------t--14 BURNLE IIIIIII11 '11111111111 '11/ BRAQFORD LEEDS I ~---+------+-- 3 I i . 1\\\\11 \ HUD~ERSFIELD'-+-II---12 RTHDALE IIIIII ' ~RSDEN 'f - I BURY!JIIIll!IC-..~~+--=:-=- - BARNSLEY BOLTON --I [11111 1 l OPENISTONE OLANGSETT' MANCHESTER Land above 1000' 30Sm 70 Moorland marathons Philip Brockbank Though the Pennine moors lack much of the beauty of the Lakeland fells and the splendour of the Welsh mountains, the more strenuous walks across them have given pleasure and not a little sport-especially in winter-to many an Alpine and even Himalayan climber. For the moorland lover based on Man chester, the only part of the Pennine worth serious consideration begins at a point 6 miles SSW of Skipton on the crest of the Colne-Keighley road, or, as easier of access, at Colne itself, and after a crow's flight of 37 miles roughly SSE ends at the foot of the steep slopes of Kinder Scout a mile N of Edale. We can also include the moors which towards the end of that range extend E and SE to nurse the infant Derwent as far as Ladybower on the main road from Glossop to Sheffield. For about the first 28 miles of that Colne to Edale flight the moors are of the conventional type. Their surface consists mainly of coarse grass with bil berry and heather in various states of roughness, culminating in the robust tussocks known as Scotchmen's heads, or (more politely) Turks' heads, which when spaced apart at a critical distance slightly less than a boot's width, thereby tending to twist the boot when inserted between them, constitute the worst going in the Kingdom apart from the rock-and-heather mixture of the Rhinogs of North Wales. -

Chapel-En-Le-Frith the COPPICE a Stunning Setting for Beautiful Homes

Chapel-en-le-Frith THE COPPICE A stunning setting for beautiful homes Nestling in the heart of the captivating High Peak of Derbyshire, Chapel-en-le-Frith is a tranquil market town with a heritage stretching back to Norman times. Known as the ‘Capital of the Peak District’, the town lies on the edge of the Peak District National Park, famous for its spectacular landscape. From The Coppice development you can pick up a number of walking trails on your doorstep, including one which leads up to the nearby Eccles Pike and its magnificent 360 views. Alternatively, you can stroll down to the golf course to play a round in a striking rural setting or walk into the town centre to enjoy a coffee in one of the many independent cafés. People have been visiting this area for centuries and not just for the exquisite scenery: the area is well connected by commuter road and rail links to Buxton and Manchester, while the magnificent Chatsworth House, Haddon Hall and Hardwick Hall are all within easy reach. View from Eccles Pike Market Cross THE COPPICE Chapel-en-le-Frith Market Place Amidst the natural splendour of the High Peak area, The Coppice gives you access to the best of both worlds. The town has a distinct sense of identity but is large enough to provide all the amenities you need. You can wander through the weekly market held in the historic, cobbled Market Place, admire the elaborate decorations which accompany the June carnival, and choose to dine in one of Imagine the many restaurants and pubs.