BRISTOL and the AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY by C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSI of NSW Article

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article USI Vol59No2 June08 13/5/08 8:32 AM Page 13 LECTURES AND PRESENTATIONS Air transport operations – past, present and future an address1 to the Institute on 25 March 2008 by Air Commodore B. G. Plenty, AM, RAAF2 Commander, Air Lift Group Air transport, both strategic and tactical, is an integral component of contemporary military operations across the broad spectrum from warfighting to humanitarian relief. In the Royal Australian Air Force, this capability is provided by the Air Lift Group. Here, the Group’s commander, “Jack” Plenty, provides an overview of the Air Lift Group, its genesis in World War II, its current capability and the personnel, equipment and infrastructure challenges that it is now facing. In the Royal Australian Air Force today, the air • No. 34 Squadron (2 x BBJ and 3 x CL604 transport capability is provided by the Air Lift Group Challenger VIP transport aircraft), Fairbairn; whose mission is to conduct and sustain combat airlift • No. -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

The Official Magazine for RAF Wittering and the A4 Force W in Ter

Winter 2019 Winter WitteringThe official magazine for RAF Wittering and the A4 Force View WINTER 2019 WITTERING VIEW 1 Features: In the Spotlight - Community Support Future • Accommodation Model • Fighting Ovarian Cancer 2 WITTERING VIEW WINTER 2019 WINTER 2019 WITTERING VIEW 3 Editor Welcome to the Winter edition of Foreword the Wittering View. With Autumn now a distant It has been a busy first few memory, and as our thoughts turn months for me. But I wanted to Christmas, we can’t quite believe to start simply by saying thank how quickly this year has gone! you for all the support that RAF Wittering is an incredibly you have given me, as well as to say thank you to all of our busy Station but despite this incredible personnel who have everyone has still found time continued to support both the throughout the year to send in their Station and the A4 (Logistics and articles for which we are grateful. As Engineering) Force Elements. a result, this issue features a good Some of the recent highlights cross-section of the activities taking have included; place here at Wittering. • The Annual Formal Visit by Air From the recent Annual Formal Officer Commanding (AOC) 38 Visit (page 6) and Annual Reception Group, Air Vice-Marshal Simon (page 8) to the various exercises Ellard. The AOC spent 30 hours that Station personnel have been on Station and was able to see involved with (Exercise COBRA the tremendous work that our WARRIOR – page 12 and Exercise personnel from across the Whole JOINT SUPPORTER – page 9), it does Force conduct on a daily basis. -

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series: Stirling Produced from Information Contained Within The Gazetteer for Scotland. Tourist Guide of Stirling Index of Pages Introduction to the settlement of Stirling p.3 Features of interest in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.5 Tourist attractions in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.9 Towns near Stirling p.15 Famous people related to Stirling p.18 Further readings p.26 This tourist guide is produced from The Gazetteer for Scotland http://www.scottish-places.info It contains information centred on the settlement of Stirling, including tourist attractions, features of interest, historical events and famous people associated with the settlement. Reproduction of this content is strictly prohibited without the consent of the authors ©The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2011. Maps contain Ordnance Survey data provided by EDINA ©Crown Copyright and Database Right, 2011. Introduction to the city of Stirling 3 Scotland's sixth city which is the largest settlement and the administrative centre of Stirling Council Area, Stirling lies between the River Forth and the prominent 122m Settlement Information (400 feet) high crag on top of which sits Stirling Castle. Situated midway between the east and west coasts of Scotland at the lowest crossing point on the River Forth, Settlement Type: city it was for long a place of great strategic significance. To hold Stirling was to hold Scotland. Population: 32673 (2001) Tourist Rating: In 843 Kenneth Macalpine defeated the Picts near Cambuskenneth; in 1297 William Wallace defeated the National Grid: NS 795 936 English at Stirling Bridge and in June 1314 Robert the Bruce routed the English army of Edward II at Stirling Latitude: 56.12°N Bannockburn. -

2012 ELECTRAIL COLOUR SLIDES LIST 30 Page 3

Page 1 Page 1 ELECTRAIL COLOUR SLIDES List 30 List 30 01/02/12 Electric Railway Society, 17 Catherine Drive, SUTTON COLDFIELD, England, B73 6AX. ELECTRAIL is a range of colour slides depicting tramcars in Britain and overseas, electric trains, and coastal pleasure steamers – especially those that connected with electrified railway routes such as along the Clyde Estuary or along the South Coast of England. The slides are 35mm colour images generally mounted in plastic mounts measuring 2” x 2”. A very few of our earliest views are in card mounts of the same size. It is now becoming difficult to find photographic labs that are capable of producing these copy slides in quite large numbers at a reasonable cost and as a result the stocks of most of the slides contained in this list are becoming low and it will be impossible to obtain more copies of many of them. Where stocks are particularly low this is indicated in the list. UK orders. Please send to address at top of this page. Each slide costs 30p and cheques should be made payable to “Electric Railway Society”. Orders sent to UK addresses are post free. Overseas orders. Slides cost 30p each. The cost of processing cheques drawn on an overseas bank is prohibitive but cheques drawn on a UK bank are accepted. An inexpensive means of payment from the nations using the Euro, the US $, or the Canadian $ is to enclose pay for the order using €, US$ or Can $ currency notes. Please do not use coins since these can go missing in the post. -

Scenes of Village Life, 1920-1970

Hook Norton Local History Group Scenes of Village Life, 1920-1970 The impact within the village of depression between the wars and of total war after 1939 have been well captured in the following series of short articles that have appeared in the Hook Norton Newsletter since 2017. Most of them have been written by James Tobin, himself a native of the village who grew up here during the latter part of the period. But we begin with a childhood memory of the depression by Geoff Hillman, who was born in the village in 1919. On the Dole: Baking the Yorkshire Pudding page 2 The Hooky Bus 4 Supplying Petrol for Motor Vehicles 6 Wireless in Hook Norton before Mains Electricity 9 Special Branch investigate Security Breach 11 Hooky Children Do Their Wartime Bit 14 The Build-up to D-Day 16 School closes due to V-1 Flying Bomb attacks 18 Betty's Last Days at Brymbo 20 The Joy of Coach Travel 21 The Air Training Corps in Hook Norton 23 The Last Hooky Picture Show 25 1 Hook Norton Local History Group 1 On the Dole: Baking the Yorkshire Pudding I remember ‘Baker Haynes’. His bakery was in the area then called Downtown, at the bottom of Bell Hill, across from Woodbine Cottage where we lived in the late twenties and thirties. As an eight-year old I loved the smell of the bread and, if I was sent across to get some from the bakery, I always got into trouble with my mother for fingering a hole in the crust and pulling out some fresh bread. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

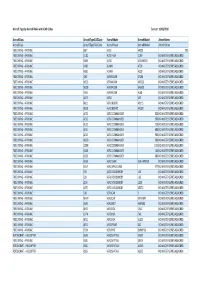

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016 AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AJ27 ACAC ARJ21 700 FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE CUB2 ACES HIGH CUBY NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE SACR ACRO ADVANCED NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A700 ADAM A700 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A500 ADAM A500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE F26T AERMACCHI SF260 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M326 AERMACCHI MB326 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M308 AERMACCHI MB308 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE LA60 AERMACCHI AL60 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AAT3 AERO AT3 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB11 AERO BOERO AB115 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB18 AERO BOERO AB180 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC52 AERO COMMANDER 520 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC50 AERO COMMANDER 500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC72 AERO COMMANDER 720 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC6L AERO COMMANDER 680 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC56 AERO COMMANDER 560 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M200 AERO COMMANDER 200 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE JCOM AERO COMMANDER 1121 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE VO10 AERO COMMANDER 100 NO MASTER -

PREFACE to 1895 EDITION, OUTLINE of CONTENTS and INDEX to COMPANIES LISTED in 1895 (PDF File

PREFACE TO 1895 EDITION, OUTLINE OF CONTENTS & INDEX TO COMPANIES LISTED IN 1895 By 1895 the Stock Exchange Official Yearbook had settled into a format that it was to stay with for the duration. We reproduce the Preface, Outline of Contents and the Index to companies listed in 1895 to give readers an idea of the typical organisation of a yearbook, and of the great variety of companies covered in this and in future volumes. PREFACE. The year 1894 has not proved so favourable to business as was expected. This is chiefly due to the further considerable decline in the prices of natural products, and to some extent to the difficulty in bringing to a conclusion the tariff and other reforms in the United States to which President Cleveland had put his hand. But the year closes with a nearly complete absence of disturbing causes, though the prices of produce are still at their lowest, and the return to commercial and agricultural prosperity is in all parts of the world proceeding at an abnormally slow rate. But it is generally admitted that the worst is now more than over. This is an immense gain in itself, especially as regards Stock Exchange securities, amongst which selling from fear or necessity no sooner ceases than an upward movement on some scale sets in. A year ago we had to report a further considerable fall in the aggregate of Stock Exchange values; but for 1894 there has been a rise in prices which more than outsets the decline then reported, and to all appearance the upward movement is still in progress. -

Tfgb Bristol Bath Rapid Transit Plan

A RAPID TRANSIT PLAN FOR BRISTOL AND BATH CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................ 2 Introduction: Bristol Deserves Rapid Transit ................... 5 A Phased Programme ..................................................... 10 Main Paper Aims and Constraints ..................................................... 14 1. Transport aims 2. Practicalities 3. Politics Proposed Rapid Transit lines ........................................ 19 Bristol .......................................................................... 19 Bath ............................................................................. 33 Staffing, Organisation and Negotiations ......................... 36 Suggested Programme (Bristol area only) ........................ 36 Appendix:TfGB’s Bristol Rapid Transit Map ..................... 37 tfgb.org v51 17-09-20 Map by Tick Ipate 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY These proposals for a twenty-first century transport system are not from a single- issue lobby group; Transport for Greater Bristol (TfGB) offers a comprehensive package of transport and environment measures which builds on the emerging good practice found across the region such as MetroWest, the City Bus Deal in Bristol and the well-organised bus-rail interchange at Bath Spa. As we emerge from the special circumstances of the Covid crisis we need modern transport planning for active travel, health, opportunity, inclusion, social justice, and action on climate change. It’s also good for business. Mass transit is again being discussed in -

The Short Empire Ocean Air-Liner

The Short Empire Ocean Air-Liner The Short Empire Ocean Air-Liner FROM OUR COVER TO THE MODEL WORKSHOP COMES AN IMPORTANT NEW PLANE IN A FINE SOLID SCALE MODEL, COMPLETE WITH MINIATURE BEACHING GEAR. By William Winter THE Short Empire flying boat, designed for Imperial Airways' far-flung routes to the East and for the transatlantic service, is a giant as airplanes go. The span of the four-motored monoplane is 114 ft., and the length is 88 ft. 6 in. The height from the water line when afloat is 24 ft. Construction is of metal throughout. For day service, 24'passengers are carried. As a sleeper, 16 passengers will be carried. The crew numbers five. The four Pegasus 740 h.p. engines are expected to yield a top speed of approximately 200 m.p.h., and a cruising speed of 150-160 m.p.h. The wing flaps are of generous area and permit a reasonable landing speed. Our 1/8" scale model is of the Caledonia, the second Empire boat of a series of twenty-nine to be constructed. It differs from the Canopus, the first to be completed, in that the Canopus is to be placed on the Mediterranean hop in the India service, while the Caledonia is said to be intended for Atlantic flights. Incidentally, the principal difference between www.ualberta.ca/~khorne 1 Air Trails — January, 1937 The Short Empire Ocean Air-Liner these two boats that is evident to the eye is in the number of windows. Since the weight of the Caledonia is 5,000 Ibs. -

2020 Book News Welcome to Our 2020 Book News

2020 Book News Welcome to our 2020 Book News. It’s hard to believe another year has gone by already and what a challenging year it’s been on many fronts. We finally got the Hallmark book launched at Showbus. The Red & White volume is now out on final proof and we hope to have copies available in time for Santa to drop under your tree this Christmas. Sorry this has taken so long but there have been many hurdles to overcome and it’s been a much bigger project than we had anticipated. Several other long term projects that have been stuck behind Red & White are now close to release and you’ll see details of these on the next couple of pages. Whilst mentioning bigger projects and hurdles to overcome, thank you to everyone who has supported my latest charity fund raiser in aid of the Christie Hospital. The Walk for Life challenge saw me trekking across Greater Manchester to 11 cricket grounds, covering over 160 miles in all weathers, and has so far raised almost £6,000 for the Christie. You can read more about this by clicking on the Christie logo on the website or visiting my Just Giving page www.justgiving.com/fundraising/mark-senior-sue-at-60 Please note our new FREEPOST address is shown below, it’s just: FREEPOST MDS BOOK SALES You don’t need to add anything else, there’s no need for a street name or post code. In fact, if you do add something, it will delay the letter or could even mean we don’t get it.