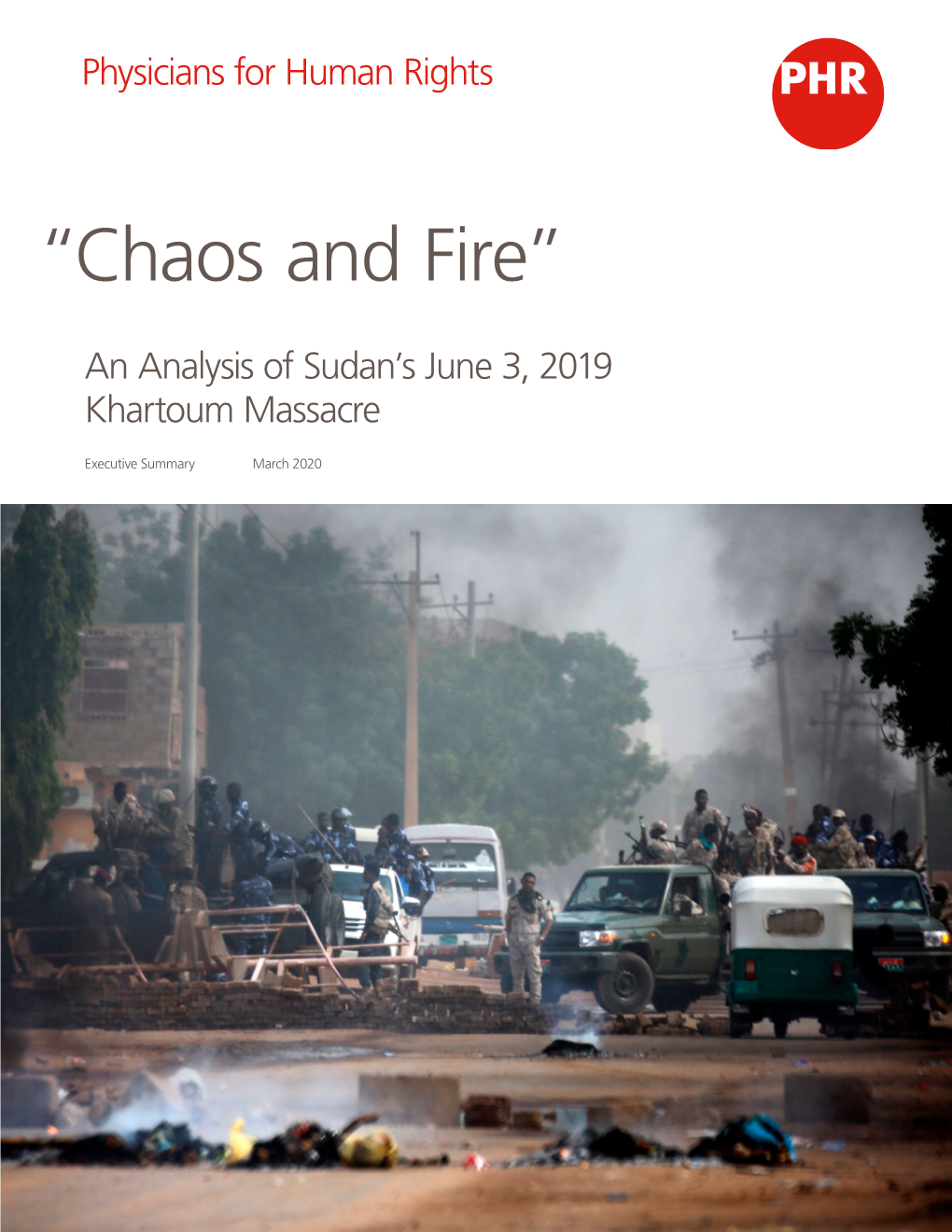

“Chaos and Fire”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan in Crisis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Faculty Publications and Other Works by History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Department 7-2019 Sudan in Crisis Kim Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Kim. Sudan in Crisis. Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 12, 10: , 2019. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 2019. vol. 12, issue 10 - July 2019 Sudan in Crisis by Kim Searcy A celebration of South Sudan's independence in 2011. Editor's Note: Even as we go to press, the situation in Sudan continues to be fluid and dangerous. Mass demonstrations brought about the end of the 30-year regime of Sudan's brutal leader Omar al-Bashir. But what comes next for the Sudanese people is not at all certain. This month historian Kim Searcy explains how we got to this point by looking at the long legacy of colonialism in Sudan. Colonial rule, he argues, created rifts in Sudanese society that persist to this day and that continue to shape the political dynamics. -

Sudan 2012 Scenarios for the Future

Sudan 2012 Scenarios for the future Jaïr van der Lijn Contents Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Methodology.............................................................................................. 2 A Sudanese future history 2009–2012......................................................... 4 Sudan in this scenario in 2012 .................................................................... 5 Suggestions and policy options for the international community in this scenario in 2012......................................................................................... 6 Border Wars (War – Secession)...................................................................... 7 A Sudanese future history 2009-2012 ......................................................... 7 Sudan in this scenario in 2012 .................................................................... 8 Suggestions and policy options for the international community in this scenario in 2012......................................................................................... 9 CPA Hurray! (No War – United) ................................................................. 10 A Sudanese future history 2009-2012 ....................................................... 10 Sudan in this scenario in 2012 .................................................................. 11 Suggestions and policy options for the international community in this scenario in 2012...................................................................................... -

June 2020 Query Code Q10-2020 Contributing EU+ COI -- Units (If Applicable)

COI QUERY Country of Origin Sudan Main subject Rapid Support Forces Question(s) 1. Are there any reports on the cooperation between the Rapid Support Forces/Janjaweed and the Sudanese intelligence services (NISS) in the period of April 2019 – March 2020? - Introductory note on the Rapid Support Forces 2. Is there any information on members of particular ethnic groups, religions or professions being targeted by the Rapid Support Forces/Janjaweed in Darfur and the Two Areas (South Kordofan and Blue Nile) in the period of April 2019 – March 2020? If yes, is there any information on the means of monitoring of such people? - Targeting by the RSF - Examples of incidents attributed to the RSF in the reference period - Monitoring by the RSF Date of completion 2 June 2020 Query Code Q10-2020 Contributing EU+ COI -- units (if applicable) Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the EASO COI Report Methodology and EASO Writing and Referencing Guide. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. -

The Making and Unmaking of a Revolution: from the Fall of Al-Bashir to the Return of Janjaweed

The Making and Unmaking of a Revolution: From the Fall of al-Bashir to the Return of Janjaweed By Claudio Butticè After more than 30 years of ruling Sudan, in April 2019 the dictator Omar al-Bashir was finally deposed by the military following an irrepressible explosion of civil unrest. In less than five months of protest following the intolerable austerity politics imposed by al-Bashir’s administration, the Sudanese population found unexpected energy and cohesion in fighting peacefully to obtain a democratic government. As crowds of demonstrators from all across the country converged on the capital to join the civil movement, art flourished, and a renewed sense of freedom gave voice once again to those who found the strength to break their chains. Women, such as the “Nubian Queen” Alaa Salah (dubbed “the woman in white”), have been at the forefront of the demonstrations, and people from all walks of life who have been denied their basic human rights rose to finally end their silence. However, things went south in June when the army refused to hold its promise to guarantee a three- year transition period before a new civilian rule could be established. Although the protest organisers rebuked the military’s decision to scrap the agreement, the Transitional Military Council (TMC) acted with unexpected brutality, killing more than one hundred Sudanese activists during the Khartoum massacre. Today, the situation is extremely tense, with claims that the United Arab Emirates is arming the violent counter-revolution. Furthermore, back-and-forth negotiations after a general strike have brought the whole country to a halt. -

Safeguarding Sudan's Revolution

Safeguarding Sudan’s Revolution $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ 2FWREHU +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. From Crisis to Coup, Crackdown and Compromise ......................................................... 3 III. A Factious Security Establishment in a Time of Transition ............................................ 10 A. Key Players and Power Centres ................................................................................. 11 1. Burhan and the military ....................................................................................... 11 2. Hemedti and the Rapid Support Forces .............................................................. 12 3. Gosh and the National Intelligence and Security Services .................................. 15 B. Two Steps Toward Security Sector Reform ............................................................... 17 IV. The Opposition ................................................................................................................. 19 A. An Uneasy Alliance .................................................................................................... 19 B. Splintered Rebels ...................................................................................................... -

RYS Sudan Country Report

SUDAN COUNTRY REPORT POPULATION Sudan is the 31st largest country in the world in African ethnicity (Fur, Beja, Nuba and Fallata) terms of population (45,561,556). 12.5% Sudan has over 500 ethnic groups, with the largest being the Sudanese Arab and the African ethnic groups Fur, Beja, Nuba & Fallata. Christian 5.5% There are over 400 languages spoken in Sudan, but the two official ones are Arabic and English, with Sudanese Arab Nubian, Ta Bedawie and Fur following up in 87.5% popularity. 64.5% of the population lives in rural areas. 44-89 years Sunni Muslim 20-44 years 91.7% 0-19 years The majority of the Sudanese population is 0% 20% 40% 60% under 19 years old. CIA World Factbook Sudan: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/su.html INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS REFUGEES Over 2 million people have been internally Over 1 million refugees have displaced in Sudan, the majority living in entered Sudan, the majority staying in South, North and Central Darfur States. Due Darfur, Khartoum, Kassala or the to ongoing violence in Darfur since the White Nile region. Over 1/3 of them genocide in 2003 and tribal violence, many are children. Syrian Sudanese people have been forced to flee 8.5% their homes. A large part have also fled Eritrean 11.2% because of food insecurity and natural INFRASTRUCTURE disasters such as earthquakes, flooding and drought. UNHCR (2020), Sudan Fact Sheet South Sudanese IDMC Sudan Report: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/sudan 77.7% HEALTH AND DISEASE 44.5% of the Sudanese population has no access to clean water. -

Sudan: a Country at Crossroads - Part V

Sudan: A Country at Crossroads - Part V By The Elephant Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Sudan: A Country at Crossroads - Part V By The Elephant Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Sudan: A Country at Crossroads - Part V By The Elephant Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Sudan: A Country at Crossroads - Part V By The Elephant Published by the good folks at The Elephant. The Elephant is a platform for engaging citizens to reflect, re-member and re-envision their society by interrogating the past, the present, to fashion a future. Follow us on Twitter. Sudan: A Country at Crossroads - Part V By The Elephant The African Union-led process to arrive at a conclusive agreement on the filling and subsequent operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) did not yield the expected results. Negotiations between legal and technical experts from Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan to draw up a binding document concluded without consensus at the end of August. -

They Were Shouting 'Kill Them'

HUMAN RIGHTS “They Were Shouting ‘Kill Them’” Sudan’s Violent Crackdown on Protesters in Khartoum WATCH “They Were Shouting ‘Kill Them’” Sudan’s Violent Crackdown on Protesters in Khartoum Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37854 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37854 “They Were Shouting ‘Kill Them’” Sudan’s Violent Crackdown on Protesters in Khartoum Map of Sit-in Area ................................................................................................................. i Glossary ............................................................................................................................... ii Summary .............................................................................................................................. -

Inspection of Country of Origin Information

Inspection of Country of Origin Information December 2020 David Bolt Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration Inspection of Country of Origin Information December 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 50(2) of the UK Borders Act 2007 February 2021 © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents This publication is also available at www.gov.uk/ICIBI Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, 5th Floor, Globe House, 89 Eccleston Square, London SW1V 1PN United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-5286-2416-9 CCS1220753316 02/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Our purpose To help improve the efficiency, effectiveness and consistency of the Home Office’s border and immigration functions through unfettered, impartial and evidence-based inspection. All Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration inspection reports can be found at www.gov.uk/ICIBI Email us: [email protected] Write to us: Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration 5th Floor, Globe House 89 Eccleston Square London, SW1V 1PN United Kingdom Contents Foreword 2 1. Scope 3 2. -

COI QUERY Disclaimer

COI QUERY Country of Origin Sudan Main subject Non-Arab Darfuris in Khartoum Question(s) Information on the situation of non-Arab Darfuris (including Fur, Zaghawa, Masalit, Bergu, Dajo) in Khartoum, in the period of August 2019 - May 2020: - living conditions and access to employment, - instances of ill-treatment and attacks, - access to justice. Date of completion 16 June 2020 Query Code Q11-2020 Contributing EU+ COI -- units (if applicable) Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the EASO COI Report Methodology and EASO Writing and Referencing Guide. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. The target audience is caseworkers, COI researchers, policy makers, and decision making authorities. The answer was finalised on 16 June 2020. Any event taking place after this date is not included -

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Sudan Van Maart 2021

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Sudan Maart 2021 Pagina 1 van 117 Algemeen Ambtsbericht Sudan | maart 2021 Colofon Plaats Den Haag Opgesteld door Afdeling Ambtsberichten (DAF/AB) Pagina 2 van 117 Algemeen Ambtsbericht Sudan | maart 2021 Inhoudsopgave Colofon ..........................................................................................................2 Inhoudsopgave ...............................................................................................3 Inleiding .........................................................................................................5 1 Politieke ontwikkelingen ............................................................................. 7 1.1 Transitieregering .............................................................................................7 1.1.1 Civiele component ...........................................................................................8 1.1.2 Militaire component .........................................................................................9 1.1.3 Fricties ...........................................................................................................9 1.2 Nieuwe politieke partijen ................................................................................ 10 1.3 Oppositie ...................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Gewapende oppositie ..................................................................................... 10 1.3.2 Niet-gewapende oppositie .............................................................................. -

Walk to Bethlehem 10/12/2020 to 10/18/2020 Week 4 Report This Week We Traveled 818 Miles and Had 29 Participants

Walk to Bethlehem 10/12/2020 to 10/18/2020 Week 4 Report This week we traveled 818 miles and had 29 participants. We had ended the previous week in Khartoum but had used up over 1000 miles in Week Three to get there and so we waited to explore the city until the beginning of week 4. Khartoum is the place where the White Nile which we have been following and the Blue Nile converge into the Nile. Divided by these two parts of the Nile, Khartoum is a tripartite metropolis with an estimated overall population of over five million people, consisting of Khartoum proper, and linked by bridges to Khartoum North and Omdurman to the west. This picture below shows the distinctly lighter White Nile and the darker Blue Nile. Satellite view of Khartoum with White and Blue Niles Khartoum was founded in 1821 as part of Ottoman Egypt, north of the ancient city of Soba. The Siege of Khartoum in 1884 led to the capture of the city by Mahdist forces and a massacre of the defending Anglo-Egyptian garrison. It was re-occupied by British forces in 1898 and served as the seat of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan government until 1956, when the city became the capital of an independent Sudan. The city has continued to experience unrest in modern times. Khartoum is an economic and trade center in Northern Africa, with rail lines from Port Sudan and El-Obeid. It is served by Khartoum International Airport, with a new airport under construction. Several national and cultural institutions are located in Khartoum and its metropolitan area, including the National Museum of Sudan, the Khalifa House Museum, the University of Khartoum, and the Sudan University of Science and Technology.