University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary of Sewing Terms

Glossary of Sewing Terms Judith Christensen Professional Patternmaker ClothingPatterns101 Why Do You Need to Know Sewing Terms? There are quite a few sewing terms that you’ll need to know to be able to properly follow pattern instructions. If you’ve been sewing for a long time, you’ll probably know many of these terms – or at least, you know the technique, but might not know what it’s called. You’ll run across terms like “shirring”, “ease”, and “blousing”, and will need to be able to identify center front and the right side of the fabric. This brief glossary of sewing terms is designed to help you navigate your pattern, whether it’s one you purchased at a fabric store or downloaded from an online designer. You’ll find links within the glossary to “how-to” videos or more information at ClothingPatterns101.com Don’t worry – there’s no homework and no test! Just keep this glossary handy for reference when you need it! 2 A – Appliqué – A method of surface decoration made by cutting a decorative shape from fabric and stitching it to the surface of the piece being decorated. The stitching can be by hand (blanket stitch) or machine (zigzag or a decorative stitch). Armhole – The portion of the garment through which the arm extends, or a sleeve is sewn. Armholes come in many shapes and configurations, and can be an interesting part of a design. B - Backtack or backstitch – Stitches used at the beginning and end of a seam to secure the threads. To backstitch, stitch 2 or 3 stitches forward, then 2 or 3 stitches in reverse; then proceed to stitch the seam and repeat the backstitch at the end of the seam. -

2000 Proceedings Cincinnati, OH

Cincinnati, OH USA 2000 Proceedings DOGWOOD IN GREEN AND GOLD Tammy Abbey Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 The purpose in creating this piece is to design an elegant garment through the combination of two very different techniques, metalsmithing and sewing. This design was inspired by extensive study in both metalworking and sewing and by blooming dogwood. The garment can be described as a dark green, fully lined dress in a polyester crepe satin. It is designed with princess lines and a gold charmeuse godet in the back. The dress is strapless and supported by the metal "lace." The "lace" is formed with brass blossoms and leaves that wrap the shoulders and overlap the front and the back of the dress. Brass blossoms also accent the godet. Construction began with an original pattern which was hand drafted. A muslin test garment was sewn, fitted and used to adjust the pattern. The main body of the dress was sewn and an invisible zipper was installed. A godet was sewn into the back. A polyester lining was sewn and then added to the dress. After the body of the dress was completed, the metal work began. Blossoms and leaves were cut from sheet brass. Then each was individually chased (hand shaped with the use of hammers and tools.) The pieces were given a copper patina (coloring) and brass brushed to a matte golden color. A dress form was used to assemble a base web of brass chain onto which the blossoms were sewn into place with thread and wire. Two blossoms and chain were added in the back to accent the godet and to contain it. -

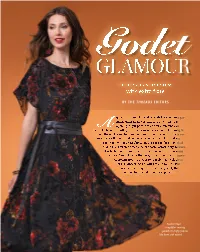

GLAMOUR Create a Custom Dress with Extra Flare

Godet GLAMOUR Create a custom dress with extra flare BY THE THREADS EDITORS godet is a triangular wedge of fabric sewn into a gar- ment, either in an existing seam or within a cut A opening. Its purpose is to add circumference, or are, at a hemline. With godets, you can achieve a body-skimming t through the bodice and hips and fullness around the hem. Godets cre- ate a pretty silhouette and enhance movement in a skirt or dress. ey require precise stitching, but there is a foolproof method that relies on fusible tape to install the in-seam variety. To learn the technique, try making the dress shown with six in-seam godets. A template for the design, in six sizes for bust mea- surements from 30 inches to 52 inches, is available at readsMagazine.com. Once you know the godet insertion technique, you can easily apply the method to tunic, skirt, or dress projects. Fusible tape simplifies sewing godets in shifty fabrics like burn-out velvet. 36 THREADS T211_CU_Godets.indd 36 7/23/20 1:24 PM FABRIC OPTIONS Godets are shown to advantage in light- weight, drapey fabrics. In a owing textile, a godet hangs beautifully when still, and Add godets in the seams for greater swings out gracefully when the body circumference at the hem. This simple is in motion. Sti or crisp textiles design is adaptable to any figure type. create pronounced angular exten- Fabric: burn-out velvet, MoodFabrics.com. sions. Chi on, georgette, burn-out velvet, challis, charmeuse, or crepe are good fabric choices. -

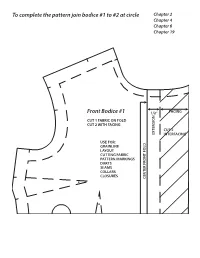

To Complete the Pattern Join Bodice #1 to #2 at Circle Front Bodice #1

To complete the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 Front Bodice #1 1/2” FACING N CUT 1 FABRIC ON FOLD CUT 2 WITH FACING CUT 2 EXTENSIO INTERFACING USE FOR: GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CLOSURES CENTER FRONT FOLD To completeTo the pattern join bodice #1 to #2 at circle TO COMPLETE THE PATTERN JOIN BODICE #1 TO #2 AT CIRCLE STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCK FRONT BODICE #2 Front Bodice #2 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 19 STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS To complete the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Back Bodice #3 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: CK SEAM GRAINLINE LAYOUT CUTTING FABRIC CK FOLD PATTERN MARKINGS DARTS SEAMS COLLARS CENTER BA CUT HERE FOR CENTER BA To completeTo the pattern join bodice #3 to #4 at circle STITCH TO MATCHPOINTS FOR DART TUCKS Back Bodice #4 Chapter 2 Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MATCHPOINT Front Skirt #5 CUT 1 FABRIC USE FOR: V SHAPED SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED/ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM CENTER FRONT FOLD Chapter 4 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Front Yoke #6 CUT 1 FABRIC CUT 1 INTERFACING USE FOR: V SHAPE SEAM WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH C. F. FOLD C. F. MATCHPOINT Chapter 4 Chapter 6 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 14 Chapter 17 MARK DART POINT HERE Back Skirt #7 CUT 2 FABRIC USE FOR: SEAMS ZIPPERS WAISTBAND WAIST FACING BIAS WAIST FINISH CURVED ALINE HEM BIAS FALSE HEM Chapter 4 CUT ON FOLD Chapter 12 Chapter 17 H TC NO WHEN -

Fabric Manipulation and Its Impact on Fashion Designs Education (Part 1)

IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 9, Issue 5 Ser. I. (Sep. - Oct .2019), PP 43-52 www.iosrjournals.org Fabric Manipulation and its impact on Fashion Designs Education (part 1) Nashwa El Shafei. PhD1, 2Laila Al Maghrabi. PhD Ready-made garment Technology'sReadymade Garment 1Faculty of Applied Arts Damietta University- 5th Assembly 2Higher Institute of Applied Arts Corresponding Author: Nashwa El Shafei PhD Abstract: The present research demonstrates an interaction technique as fabric implementations for putting garments on a three-dimensional character with manipulating them with its application on fashion. Furthermore to realize and examine the potential of the fabrics and materials which could be manipulated using different techniques and processes to innovative designs and artwork which could be applied to fine art, originate textile or fashion scenario. On the other hand, to develop different ways of altering fabric to provide contrasts, to create a sense of fullness, and create surface effects. Some of these methods are very old, but contemporary fabric artists and fashion designers continued to use them and adapt them in new styles. Key words: Fabric implementations,fullness,surface effects, contemporary fabric. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 27-08-2019 Date of Acceptance: 11-09-2019 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

2019 Proceedings Las Vegas, Nevada

Las Vegas, Nevada 201 9 Proceedings 6 Wire: Flow Belinda T. Orzada, M. Jo Kallal, Cheyenne Smith, Mikayla DuBreuil, and Wing Tang Key words: FEA Model, music, performance attire, apparel design Conceptual statement The flow of notes on sheets of music were visually translated to an undulating ribbon effect on an evening dress for an erhu musician’s performance attire. The impetus for this design came from a call from a colleague in the music department at my university requesting performance attire for a major venue for the three-person musical ensemble, 6-Wire in which he performs and also directs. Usually each member of the group purchases garments from retail stores to wear during performances, but this event was special, a premiere at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Custom performance wear was a new experience, but opportune for such a significant event. With the assistance of a design team, I ultimately designed and executed two garments for each of the three musicians to wear at this and future performances; the focus of this paper is one custom design for the female musician who plays an erhu. Aesthetic properties and Visual Impact “Line, material and decorative detail combine to create [a] costume’s movement quality” (McLean, 2012, p. 206). Performance attire for musicians must allow expression and be aesthetically pleasing, while at the same time be perfectly fitted to the musician to enhance movement not hinder it. Lamb’s and Kallal’s (1992) FEA Consumer Needs Model provided the theoretical framework for this design. Garments for musical performances necessitate a perfect balance between the three components of the FEA Model. -

Design #1505886

Design #1505886 Design #1505886 Dress - Bodycon (knit fabrics!) - Below knee length - Regular armholes - Seashell neckline - No collar - Closure from neckline to hem with folded placket - Dress without waist seam - No waist seam, godet skirt - Princess front seam: neck to waist - Back princess seam armhole to waist - No sleeves Note on seam allowances: - If the pattern has double contour the seam allowances are included. - If the pattern has single contour, the seam allowances are NOT included and need to be added when laying out the pattern. Note on length of fabric: Attention! The amount of fabric needed for your pattern is not included. It will depend on the selected pattern size, the width, and design of the fabric you plan to use. You are welcome to use the Online Fabric Estimator to make calculations. Alternatively, print all the paper patterns and lay them out at the width of fabric you plan to use (usually from 90 to 150 cm). Measure how much fabric you will need. Don't forget to account for pieces that need to be cut multiple times and pieces that are cut on the fold. PRINTING: Please use Adobe Reader software to open your PDF pattern. You can get Adobe Reader free of charge at this link - https://get.adobe.com/reader/. Make sure you print your patterns at actual size (100%% scale or None) and on single sides of plain A4 paper. Verify that the print out size is to the correct scale by measuring the test square on the first page. The upper edge of the square features a centimeter scale, and the bottom edge features an inch scale. -

Pattern-Matched Panels with Center Godet Godet Inserts Are Omnipresent in Designer Runways, Spotted in Elegant Gowns and Couture Clothing

Full Godet Medium Full Godet Soft Full Godet Rowley How-To Guide Pattern-Matched Panels with Center Godet Godet inserts are omnipresent in designer runways, spotted in elegant gowns and couture clothing. See how we’ve incorporated this sophisticated fabrication technique into stationary panels that just Materials & Supplies break the floor. In our drapery treatments, we’ve used welt cord to outline the godet and a decorative Rowley Products SKU button for added detail and visual interest. Hanes Classic Napped Sateen LN49/ R-TEX Heavy Weight Interlining RN12/ Drapery Weights SW37 John James Hand Sewing Needles TP116 Professional Shears / Scissors CU22 Fabric Stapler WW70 Fabric Stapler Staples WW71 Magnetic Fabric Staple Remover WW72 Glass Head Straight Pins TP49 Drapery Pins DP53 Fringe Adhesive FA10 Snap Together Button Forms - #45 FCB45 R-TEX Micro Welt Cord WC85 Sausage Bead Weight Chain SW80 Skirtex Stiffener SKX55/ Pattern-Matched Panels with Center Godet: Step-By-Step Instructions This how-to guide covers the steps to plan fabricate and install a stationary, pleated-to-pattern panel with a center godet. Our panel finished at 108" with one full godet at the center pleat that finished 24" tall. I planned for an 8" header and to pleat the panel to pattern. The face fabric was cut plus ½" longer in both the header and hem to allow for seam allowances for the top and bottom welt cord (plan 8 ½" for hem and 16 ½" for header). What is a Godet? A Godet is a shaped piece of fabric that is inserted into a panel (or skirt) to add flare in one location. -

Curriculum Guide. Grade 8. Louisiana State Dept. of Education, Bato

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 296 931 SO 019 166 TITLE Acadians of Louisiana: Curriculum Guide. Grade 8. Bulletin 1780. INSTITUTION Louisiana State Dept. of Education, Baton Rouge. Div. of Academic Programs. PUB DATE [873 NOTE 237p.; Acadian Odyssey Bicentennial Commission and the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana co-sponsored the development of this publication. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Course Content; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; *Cultural Education; Cultural Influences; Curriculum Development; Folk Culture; *Grade 8; History; History Instruction; Information Sources; Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Learning Activities; Program Content; Resource Units; *Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; *State History; State Programs; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Acadians; Cajuns; *Louisiana ABSTRACT This document, a supplement to the "Louisiana Studies Curriculum Guide," was designed to enhance junior high school students' appreciation for the Acadian settlers impact on Louisiana history and culture. A course outline presents four units of study that include: (1) early history; (2) life in Louisiana; (3) social and cultural life; and (4) the evolving and modern Cajuns. Each unit is divided into specific sections that contain: (1) generalization, concept, and learner outcome statements; (2) a content outline; and (3) suggested activities. A 50-item bibliography and glossary of terms are provided. Appendices include: (1) a suggested teaching timetable; (2) a teacher's reference entitled, "Louisiana French Heritage"; (3) student handouts; (4) maps; (5) Acadian music and dances; (6) suggested French language learning objectives and activities; (7) an overview of Louisiana French oral literature; (8) an exploration of the role and history of Cajun music in Louisiana French society; and (9) a selected collection of Acadian recipes. -

Apparel Manufacturing Glossary for Application Protocol Development

TKH OF STAND & INST. NIST 1 PUBLICATIONS A1110M 5 5b 57 4 Apparel Manufacturing Glossary for Application Protocol Development Michael E. Read U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Manufacturing Engineering Laboratory Manufacturing Systems Integration Division Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Sponsored in part by DLA Manufacturing Technology Program QC 100 NIST U56 NO. 5572 1995 NISTIR 5572 Apparel Manufacturing Glossary for Application Protocol Development Michael E. Read U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards and Technology Manufacturing Engineering Laboratory Manufacturing Systems Integration Division Gaithersburg, MD 20899 Sponsored in part by DLA Manufacturing Technology Program February 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Ronald H. Brown, Secretary TECHNOLOGY ADMINISTRATION Mary L. Good, Under Secretary for Technology NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY Arati Prabhakar, Director PREFACE The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is engaged in a project to develop product data standards to support computer integration of the apparel product life cycle. The project is sponsored by the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), and has been named the Apparel Product Data Exchange Standard (APDES) project. The APDES project utilizes the techniques being used by and developed for the Standard for the Exchange of Product Model Data (STEP). STEP is an emerging international standard for representing the physical and functional characteristics of a product throughout the product’s life cycle. Formal standards for STEP are being published under the auspices of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in the document series 10303-X. Many of the information requirements, as well as the software tools being developed to support STEP, are applicable for any manufacturing industry. -

Spelling, Capitalization, and Writing Guide

Spelling, Capitalization, and Writing Guide BASIC TERMS The Capital Club of Jackson lamé silk Cool Water (rose) a cappella (italics) The couple resides Monique Lhullier chrysanthemums aisle The couple is at home pavé crape myrtles altar The Very Reverend peau de soie Cymbidium orchid bridal peplum Dendrobium orchid bridesmaids’ luncheon CLOTHING pick-ups Eskimo buttercream frosting A-line point d’esprit lace Freesia (sing.) or Freesias (pl.) cakes – “tiered” if more than 1 layer agata (type of beading) portrait neckline Gerbera daisies (not Gerber) candelabrum (sing.) Alençon lace (option + c for symbol) princess waistline gladiola (sing.) gladioli (plural) candelabra (plural) ball gown redesigned hydrangea or hydrangeas NOT candelabras or candelabrums basque waistline (a cap B is a city) redingote hypericum berries champagne (NOT Champaign) Battenburg lace re-embroidered lace Konfetti complement (bring to perfection) bateau neckline ruched larkspur or larkspurs compliment (expression of praise) Belgian lace sabrina neckline Leonidas Rose double-ring Biedermeier schiffli embroidery or lace lily of the valley (or lilies of the valley) double-decker bus bobbinet shantung lisianthus Dr. and Rev. (Don’t use “THE” before) brooch sheath long stem or long stemmed fairy-tale (as an adjective) bustline tricotine lysimachia fairy tale (as a noun) cathedral-length Valenciennes lace Mokara orchid Father, not Fr. chapel-length V-neckline Mona Lisa roses flautist Chantilly lace soutache oriental lily (or lilies) flower girl crepe-backed Swarovski poppies hors d’oeuvres crisscross phalaenopsis ganache crocheted lace FLOWERS pittosporum great-grandmother cummerbund boutonnières Porcelana (hyphenate all forms) dropped waistline hand-tied porcelain (roses) groomsman/groomsmen duchess tussie-mussie (or tussie-mussies) Queen Anne’s lace maid of honor dupioni shantung ranunculus or ranunculuses Monsignor (Catholic Priest – use only fingertip-length Capitalize only specific breeds: ranunculaceous this title when used.) “Msgr.” flared NOT flaired Akito white (rose) seloum Mr. -

Friction Processing As an Alternative Joining Technology for the Nuclear Industry

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2015/v115n10a2 Friction processing as an alternative joining technology for the nuclear industry by D.G. Hattingh*‡, L. von Wielligh*, W. Thomas† and M.N. James‡ with many fossil-fuel fired plants reaching end-of-life, there is renewed interest in Synopsis installing additional nuclear capacity. The process of joining materials by friction is based on generating the heat Proposing friction processing as an alternative necessary to create a solid-state mechanical bond between two faying (and relatively untried) joining technology for surfaces to be joined. In simple terms, the components to be joined are the nuclear industry might be viewed as subjected to frictional heating between rubbing surfaces, causing an potentially perilous because of stringent increase in interface temperature and leading to localized softening of requirements for validation of weld and repair interface material, creating what is described as a ’third body’ plasticized layer. This plasticized zone reduces the energy input rate from frictional procedures. The intention in this paper is to heating and hence prevents macroscopic melting. The plasticized layer can introduce some modern developments in the no longer transmit sufficient stress as it effectively behaves as a lubricant friction processing arena and to outline the (Boldyrev and Voinov, 1980; Godet, 1984; Singer, 1998; Suery, Blandin, potential that these processes hold for and Dendievel, 1994). The potential for this solid-state frictional joining manufacturing of new components and for process to create high-performance joints between, for example, dissimilar maintenance and life extension of ageing materials with limited detrimental metallurgical impact, and reduced nuclear power plant.