Hitchhiker's Guide to Magnetism Bruce M. Moskowitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CERI 7022/8022 Global Geophysics Spring 2016

FerrimagnetismI I Recall three types of magnetic properties of materials I Diamagnetism I Paramagnetism I Ferromagnetism I Anti-ferromagnetism I Parasitic ferromagnetism I Ferrimagnetism I Ferrimagnetism I Spinel structure is one of the common crystal structure of rock-forming minerals. I Tetrahedral and octahedral sites form two sublattices. 2+ 3+ I Fe in 1/8 of tetrahedral sites, Fe in 1/2 of octahedral sites. FerrimagnetismII I xmujpkc.xmu.edu.cn/jghx/source/chapter9.pdf Ferrimagnetism III I www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/def_en/kap_2/basics/b2_1_6.html I Anti-spinel structure of the most common iron oxides 3+ 3+ 2+ I Fe in 1/8 tetrahedral sites, (Fe , Fe ) in 1/2 of octahedral sites. FerrimagnetismIV I Indirect exchange involves antiparallel and unequal magnetization of the sublattices, a net spontaneous magnetization appears. This phenomenon is called ferrimagnetism. I Ferrimagnetic materials are called ferrites. I Ferrites exhibit magnetic hysteresis and retain remanent magnetization (i.e. behaves like ferromagnets.) I Above the Curie temperature, becomes paramagnetic. I Magnetite (Fe3O4), maghemite, pyrrhotite and goethite (' rust). Magnetic properties of rocksI I Matrix minerals are mainly silicates or carbonates, which are diamagnetic. I Secondary minerals (e.g., clays) have paramagnetic properties. I So, the bulk of constituent minerals have a magnetic susceptibility but not remanent magnetic properties. I Variable concentrations of ferrimagnetic and matrix minerals result in a wide range of susceptibilities in rocks. Magnetic properties of rocksII I I The weak and variable concentration of ferrimagnetic minerals plays a key role in determining the magnetic properties of the rock. Magnetic properties of rocks III I Important factors influencing rock magnetism: I The type of ferrimagnetic mineral. -

Rock and Paleomagnetic Investigations Technical Detailed

NWM-USGS-GPP-06 RO Rock and Paleomagnetic Investigations Technical Detailed Procedure GPP-O NNWSI Project Quality Assurance Program U.S. Geological Survey Effective Date: pepared by: Joseph Rosenbaum Technical Reviewer: Richard Reynolds 'Branch Chief: Adel Zohdy NNWI Project Coordinator: W. Dudley Quality Assurance: P. L. Bussolini 8502210165 841130 PDR WASTE PDR Wm-II NWM-USGS-GPP- 06, RO NWM-USGS-GPP- o RO Page 2 of 13 Rock and Paleomagnetic Investigations 1.0 PURPOSE 1.1 This procedure provides a means of assuring the accuracy, validity, and applicability of the methods used to determine paleomagnetic and rock magnetic properties. 1.2 The procedure documents the USGS responsibilities for quality assurance training and enforcement, the processes and authority for procedure modification and revision, the requirements for procedure and personnel interfacing, and to whom the procedure applies. 1.3 The procedure describes the system components, the principles of the methods used, and the limits of their use. 1.4 The procedure describes the detailed methods to be used, where applicable, for system checkout and maintenance, calibration, operation and performance verification. 1.5 The procedure defines the requirements for data acceptance, documentation and control; and provides a means of data traceability. 1.6 The procedure provides a guide for USGS personnel and their contractors engaged to determining paleomagnetic and rock mag- netic properties and a means by which the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) can evaluate these activities in meeting requirements for the NNWSI repository. 2.0 SCOPE OF COMPLIANCE 2.1 This procedure applies to all USGS personnel, and persons assigned by the USGS, who perform work on the procedure as described by the work activity given in Section 1.1, or use data from such activities, if the activities or data are deemed by the USGS Project Coordinator to potentially affect public health and safety as related to a nuclear waste repository. -

Design of a Curie Point Meter

BULLETIN 69 DESIGN OF A CURIE POINT METER A. Larochelle Price, 50 cents 1961 DESIGN OF A CURIE POINT METER 3,000-1960-1818 91594-2-1 11 026: General view of Curie point meter GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA BULLETIN 69 DESIGN OF A CURIE POINT METER By A. Larochelle DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND TECHNICAL SURVEYS CANADA 91594-2-2 ROGER DUHAMEL. F.R.S.C. QUEEN'S PRINTER AND CONTROLLER OF STATIONERY OTTAWA, 1961 Price 50 cents Cat. No. M42-69 Preface Magnetic properties are rarely used to identify minerals because they are generally difficult to detect or to determine accurately. Ferromagnetic minerals are, however, an exception. Not only can a family of ferromagnetic minerals be identified from its magnetic properties, but individual members of the family can be recognized. The Curie point is one of the most reliable magnetic properties for identifying such minerals. The apparatus described in this bulletin was designed to permit the rapid, accurate measurement of the Curie point of the ferromagnetic minerals in rock specimens, and by this means to identify them. J. M. HARRISON, Director, Geological Survey of Canada OTTAWA, April 28, 1960 v CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 1 General description 1 The torsion balance 2 The recording system 6 The heating element ........ ..... 8 The electromagnet 9 Operation and calibration of the apparatus 12 Practical application . 15 Bibliography 18 Table I. Curie points of specimens of basic intrusive rocks . 16 Plate I. General view of Curie point meter Frontispiece Figure 1. Schematic view of the Curie point meter . 2 2. Longitudinal section of torsion balance 3 3. -

Rock Magnetism of Remagnetized Carbonate Rocks: Another Look

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California Berkeley on July 30, 2013 Rock magnetism of remagnetized carbonate rocks: another look MIKE JACKSON* & NICHOLAS L. SWANSON-HYSELL Institute for Rock Magnetism, Winchell School of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minnesota, US *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Authigenic formation of fine-grained magnetite is responsible for widespread chemical remagnetization of many carbonate rocks. Authigenic magnetite grains, dominantly in the super- paramagnetic and stable single-domain size range, also give rise to distinctive rock-magnetic prop- erties, now commonly used as a ‘fingerprint’ of remagnetization. We re-examine the basis of this association in terms of magnetic mineralogy and particle-size distribution in remagnetized carbon- ates having these characteristic rock-magnetic properties, including ‘wasp-waisted’ hysteresis loops, high ratios of anhysteretic remanence to saturation remanence and frequency-dependent susceptibility. New measurements on samples from the Helderberg Group allow us to quantify the proportions of superparamagnetic, stable single-domain and larger grains, and to evaluate the mineralogical composition of the remanence carriers. The dominant magnetic phase is magnetite-like, with sufficient impurity to completely suppress the Verwey transition. Particle sizes are extremely fine: approximately 75% of the total magnetite content is superparamagnetic at room temperature and almost all of the rest is stable single-domain. Although it has been pro- posed that the single-domain magnetite in these remagnetized carbonates lacks shape anisotropy (and is therefore controlled by cubic magnetocrystalline anisotropy), we have found strong exper- imental evidence that cubic anisotropy is not an important underlying factor in the rock-magnetic signature of chemical remagnetization. -

Magnetic Properties of the Magnetite-Spinel Solid Solution: Curie Temperatures, Magnetic Susceptibilities, and Cation Ordering

American Mineralogist, Volume 81, pages 375-384, 1996 Magnetic properties of the magnetite-spinel solid solution: Curie temperatures, magnetic susceptibilities, and cation ordering RICHARD J. HARRISON ANDANDREW PurNIS * Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EQ, U.K. ABSTRACT Curie temperatures (Td of the (Fe304)x(MgA1204)1-xsolid solution have been deter- mined from measurements of magnetic susceptibility (x) vs. temperature. The trend in Te vs. composition extrapolates to 0 K at x = 0.27. This behavior is rationalized in terms of the trend in cation distribution vs. composition suggested by Nell and Wood (1989), with Fe occurring predominantly on tetrahedral sites for x < 0.27. High-temperature x-T curves are nonreversible because of the processes of cation or- dering and exsolution, which occur in the temperature range 400-650 0c. The Curie tem- perature of single-phase material is shown to be sensitive to the state of nonconvergent cation order, with a difference in Te of more than 70°C being observed between a sample quenched from 1400 °C and the same sample after heating to 650°C. This interaction between magnetic and chemical ordering leads to thermal hysteresis behavior such that Te measured during heating experiments is approximately 10°Chigherthan that measured during cooling. The hysteresis is due to a reversible difference in the state of cation order during heating and cooling caused by a kinetic lag in the cation-ordering behavior. Samples with compositions in the range 0.55 < x < 0.7 undergo exsolution to a mixture of ferrimagnetic and paramagnetic phases after heating to 650°C. -

8. Data Report: Paleomagnetic and Rock Magnetic Characterization of Rocks Recovered from Leg 173 Sites1

Beslier, M.-O., Whitmarsh, R.B., Wallace, P.J., and Girardeau, J. (Eds.) Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results Volume 173 8. DATA REPORT: PALEOMAGNETIC AND ROCK MAGNETIC CHARACTERIZATION OF ROCKS RECOVERED FROM LEG 173 SITES1 Xixi Zhao,2 Brent D. Turrin,3 Mike Jackson,4 and Peter Solheid4 ABSTRACT We present detailed paleomagnetic and rock magnetic results of rock samples recovered during Leg 173. The Leg 173 cores display a multi- component magnetization nature. Variations in magnetic properties correlate with changes in lithology that result from differences in the 1Zhao, X., Turrin, B.D., Jackson, M., abundance and size of magnetic minerals. The combined investigation and Solheid, P., 2001. Data report: suggests that the magnetic properties of the “fresher” peridotite sam- Paleomagnetic and rock magnetic ples from Site 1070 are controlled mainly by titanomagnetite, with a characterization of rocks recovered from Leg 173 sites. In Beslier, M.-O., strong Verwey transition in the vicinity of 110 K, and with field- and Whitmarsh, R.B., Wallace, P.J., and frequency-dependent susceptibility curves that resemble those of tita- Girardeau, J. (Eds.), Proc. ODP, Sci. nomagnetites. These results are in excellent agreement with thermo- Results, 173, 1–34 [Online]. Available magnetic characteristics where titanomagnetites with Curie tempera- from World Wide Web: <http:// ture ~580°C were identified from the “fresher” peridotites. In contrast www-odp.tamu.edu/publications/ 173_SR/VOLUME/CHAPTERS/ to the magnetic properties observed from the “fresher” peridotites, the SR173_08.PDF>. [Cited YYYY-MM-DD] low-temperature curves for the “altered” peridotites did not show any 2Institute of Tectonics, University of Verwey transition. -

And Palaeo-Magnetism

Opening Remarks for Symposium on Rock- and Palaeo-Magnetism (IUGG Kyoto Symposium on Rock- and Palaeo-Magnetism) By Takesi NAGATA Organizer of the Symposium, GeophysicalInstitute, University of Tokyo In connexion with the International Conference on Magnetism and Crystallography, which is held on 25th-30th September 1961 at Kyoto under auspices of the International Union of Pare and Applied Physics (IUPAP) and the International Union of Crystal- lography (IUCr), an international symposium on rock-and ppalaeo-magnetism is now held at Kyoto. This symposium is organized according to request by a number of active workers in this branch of science and by many members of the Committee on Secular Variation and Palaeomagnetism of the Association of Geomagnetism and Aeronomy (IAGA) of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG). This symposium is, therefore, formally sponsored by IUGG, and may be called the "IUGG Kyoto Symposium on Rock - and Palaeo-Magnetism in 1961." We had a scientific session on "Physical Problems of Rock Magnetism" as a part of the Conference on Magnetism and Crystallography. In the session several basic problems of physical characteristics of fine grains of rock-forming metallic oxides are mainly discussed in view of solid state physics. Two main topics in that session were self-reversal of remanent magnetization and superparamagnetism and super- antiferromagnetism of very fine grains of metallic oxides. (The full papers presented to this session will be published as a part of the proceedings of the whole conference, a special volume of the Journal of Physical Society of Japan). In the present rock- and palaeo-magnetism symposium, various important topics in rock-magnetism and palaeomagnetism will be discussed more generally in connexion with geophysics and geology as well as solid state physics of materials. -

Rock-Magnetism and Ore Microscopy of the Magnetite-Apatite Ore Deposit from Cerro De Mercado, Mexico

Earth Planets Space, 53, 181–192, 2001 Rock-magnetism and ore microscopy of the magnetite-apatite ore deposit from Cerro de Mercado, Mexico L. M. Alva-Valdivia1, A. Goguitchaichvili1, J. Urrutia-Fucugauchi1, C. Caballero-Miranda1, and W. Vivallo2 1Instituto de Geof´ısica, Universidad Nacional Autonoma´ de Mexico,´ Del. Coyoacan 04510 D. F., Mexico´ 2Servicio Nacional de Geolog´ıa y Miner´ıa, Chile (Received July 14, 2000; Revised December 19, 2000; Accepted January 24, 2001) Rock-magnetic and microscopic studies of the iron ores and associated igneous rocks in the Cerro de Mercado, Mexico, were carried out to determine the magnetic mineralogy and origin of natural remanent magnetization (NRM), related to the thermo-chemical processes due to hydrothermalism. Chemical remanent magnetization (CRM) seems to be present in most of investigated ore and wall rock samples, replacing completely or partially an original thermoremanent magnetization (TRM). Magnetite (or Ti-poor titanomagnetite) and hematite are commonly found in the ores. Although hematite may carry a stable CRM, no secondary components are detected above 580◦, which probably attests that oxidation occurred soon enough after the extrusion and cooling of the ore-bearing magma. NRM polarities for most of the studied units are reverse. There is some scatter in the cleaned remanence directions of the ores, which may result from physical movement of the ores during faulting or mining, or from perturbation of the ambient field during remanence acquisition by inhomogeneous internal fields within these strongly magnetic ore deposits. The microscopy study under reflected light shows that the magnetic carriers are mainly titanomagnetite, with significant amounts of ilmenite-hematite minerals, and goethite-limonite resulting from alteration processes. -

5 Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism

5 Geomagnetism and paleomagnetism It is not known when the directive power of the magnet 5.1 HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION - its ability to align consistently north-south - was first recognized. Early in the Han dynasty, between 300 and 5.1.1 The discovery of magnetism 200 BC, the Chinese fashioned a rudimentary compass Mankind's interest in magnetism began as a fascination out of lodestone. It consisted of a spoon-shaped object, with the curious attractive properties of the mineral lode whose bowl balanced and could rotate on a flat polished stone, a naturally occurring form of magnetite. Called surface. This compass may have been used in the search loadstone in early usage, the name derives from the old for gems and in the selection of sites for houses. Before English word load, meaning "way" or "course"; the load 1000 AD the Chinese had developed suspended and stone was literally a stone which showed a traveller the pivoted-needle compasses. Their directive power led to the way. use of compasses for navigation long before the origin of The earliest observations of magnetism were made the aligning forces was understood. As late as the twelfth before accurate records of discoveries were kept, so that century, it was supposed in Europe that the alignment of it is impossible to be sure of historical precedents. the compass arose from its attempt to follow the pole star. Nevertheless, Greek philosophers wrote about lodestone It was later shown that the compass alignment was pro around 800 BC and its properties were known to the duced by a property of the Earth itself. -

Rock Magnetism and FORC Measurements

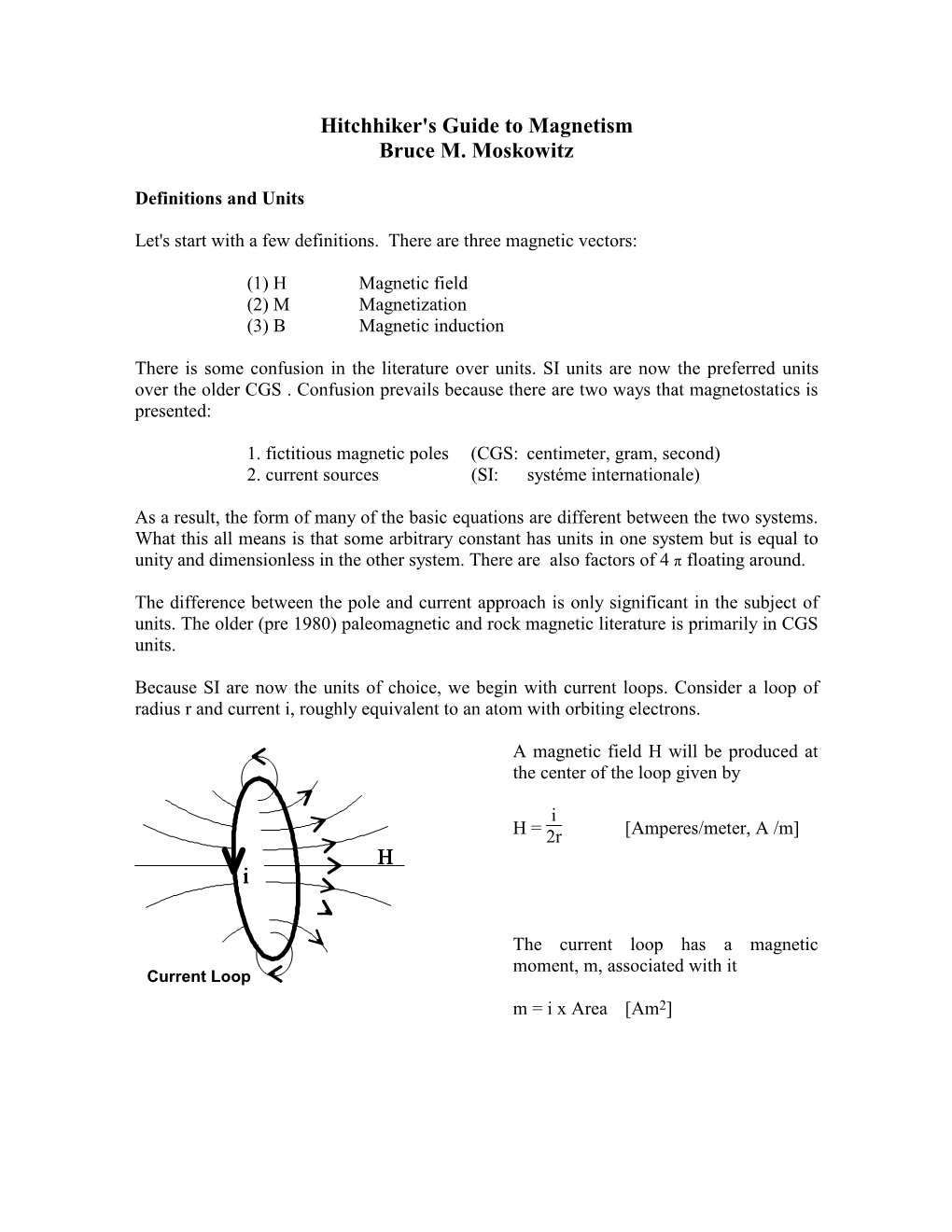

application note Rock Magnetism and First-Order- Reversal-Curve (FORC) Measurements B. C. Dodrilla, L. Spinub Abstract Mineral magnetism is one of the most powerful tools used by Earth scientists to study the large-scale structure and behavior of the Earth. Paleomagnetic and paleointensity data from rocks yield information regarding the strength of the Earth’s early geomagnetic field which is of importance for understanding the evolution of the Earth’s deep interior, surface environment and atmosphere. In geomagnetic, geological and environmental magnetic studies it is important to have reliable methods to characterize the composition, and grain size distribution of magnetic minerals within samples. For example, identification of single-domain (SD) magnetic grains is important in absolute paleointensity studies because SD grains produce more reliable results than those obtained from multi-domain (MD) grains. In paleoclimatic studies, having a means for determining the magnetic grain size distribution is important because useful environmental information is often revealed by subtle changes in grain size distribution1. Determining the composition of magnetic minerals in a rock is relatively straightforward; however identification of the domain state is more complicated. Measurement of a materials’ hysteresis loop, M(H), is very important, but suffers from the fact that it’s a bulk magnetic measurement and represents the average magnetic properties of all particles in a sample. Also, the hysteresis loop does not differentiate between mineral composition, grain size or magnetic interactions between grains which can lead to ambiguous results. This is often the case for the commonly used Day plot, which summarizes bulk magnetic properties by plotting the ratios of Mrs/Ms versus Hcr/Hc where Mrs is the saturation remanent magnetization, Ms is the saturation magnetization, Hcr is the coercivity of remanence, and Hc the coercivity. -

Magnetic Minerals As Recorders of Weathering, Diagenesis, And

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 452 (2016) 15–26 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Magnetic minerals as recorders of weathering, diagenesis, and paleoclimate: A core–outcrop comparison of Paleocene–Eocene paleosols in the Bighorn Basin, WY, USA ∗ Daniel P. Maxbauer a,b, , Joshua M. Feinberg a,b, David L. Fox b, William C. Clyde c a Institute for Rock Magnetism, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA b Department of Earth Sciences, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA c Department of Earth Sciences, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Magnetic minerals in paleosols hold important clues to the environmental conditions in which the Received 17 February 2016 original soil formed. However, efforts to quantify parameters such as mean annual precipitation (MAP) Received in revised form 15 July 2016 using magnetic properties are still in their infancy. Here, we test the idea that diagenetic processes and Accepted 17 July 2016 surficial weathering affect the magnetic minerals preserved in paleosols, particularly in pre-Quaternary Available online 4 August 2016 systems that have received far less attention compared to more recent soils and paleosols. We evaluate Editor: H. Stoll the magnetic properties of non-loessic paleosols across the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (a Keywords: short-term global warming episode that occurred at 55.5 Ma) in the Bighorn Basin, WY. We compare weathering data from nine paleosol layers sampled from outcrop, each of which has been exposed to surficial diagenesis weathering, to the equivalent paleosols sampled from drill core, all of which are preserved below environmental magnetism a pervasive surficial weathering front and are presumed to be unweathered. -

Earth's Magnetic Field

•! Origin Earth’s Magnetic Field •! Energy sources •! MHD •! Description •! Geodynamo •! Geometry •! Reversals –! Inclination and declination •! Measurements •! Strength •! Flux-gate •! Dipole and non-dipole •! Proton precession •! Variability •! SQUID •! Geocentric Axial Dipole hypothesis Magnetic Field of •! Rock Magnetism the Earth •! Physics of Magetization at magnetic dip poles ! –! induced and remnant magnetization intensity is ~70,000 nT ! –! Magnetization hysteresis –! TRM, DRM, CRM, and __RMs at magnetic equator ! •! Determination of GMP, VGP, paleo-pole. paleo intensity is ~25,000 nT! -latitudes, and APW 1 nT = 1 gamma (cgs)! •! Geophysical exploration: measuring magnetic fields Note direction relative to surface! Earth's magnetic field! magnetics At any location the magnetic field is a vector with magnitude (intensity) + direction! •! B and H: Same except for constant in free space (B=µoH), differ inside inclination = angle relative to horizontal! magnetic material (B=µoHex + Jint). Both have been called “magnetic declination = angle btw magnetic N + geographic N! field”. We will call H the “Magnetizing Field” •! Total field vector B has vertical component Z and horizontal component H. (not to be confused with the magnetizing field) –! Inclination, I=tan-1 Z/H –! tan I =2 tan (latitude) –! Declination of H measured relative to true north •! Measured using –! Flux-gate (component) or proton precession (total field) - .1 nT –! SQUID (Superconducting Quantum Interference Device) all three components to very high precision (aT –