Socioeconomic Value of Delaware Wetlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condition of Wetlands in the Broadkill River Watershed, Delaware

The citation for this document is: Rogerson,A.B., M.A. Jennette, and A.M. Howard. 2013. Condition of wetlands in the Broadkill River Watershed, Delaware. Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Watershed Assessment and Management Section, Dover, USA. 59p. Broadkill Watershed Wetland Report i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Funding for this project was provided by EPA REMAP and Region III Wetland Program Development Grant Assistance # CD-96312201-0, and the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. This research and report were made possible by many who contributed their time and expertise. Tom Kincaid and Tony Olsen with the EPA Office of Research and Development Lab, Corvallis, Oregon provided technical support with the developing the data frame and statistical weights. Many individuals dedicated their time and hard work to collecting out assessment data, including seasonal hires Jocelyn Robinson and Megan Pulver and multiple volunteers. In addition, we thank the Environmental Lab Section for use of their biomass storage and oven space and the DNERR St. Jones Reserve for use of their boat. Broadkill Watershed Wetland Report ii Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 4 WATERSHED OVERVIEW .................................................................................................... -

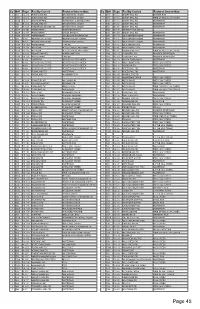

Bridge Index

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

White Clay Creek State Park Trail Plan 12-9-2011

White Clay Creek State Park Trail Plan 12-9-2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 5 Trail Plan Objectives & Goals ................................................................................. 6 Background & History .......................................................................................... 8 Regional Context ..................................................................................................................... 12 Regional Trail System .............................................................................................................. 14 Public Demand for Trail Opportunities ................................................................ 14 1998 Trail System Overview & Assessment .......................................................... 17 2010 Trail System Overview & Assessment .......................................................... 24 Existing Conditions and Maps ................................................................................................ 24 Trail Descriptions .................................................................................................................... 33 Impacts & Assessment of Today’s Trail System ...................................................................... 37 Trail Users & Uses ................................................................................................................... 39 Visitor Assessment ................................................................................................................. -

Living Blues 2021 Festival Guide

Compiled by Melanie Young Specific dates are provided where possible. However, some festivals had not set their 2021 dates at press time. Due to COVID-19, some dates are tentative. Please contact the festivals directly for the latest information. You can also view this list year-round at www.LivingBlues.com. Living Blues Festival Guide ALABAMA Foley BBQ & Blues Cook-Off March 13, 2021 Blues, Bikes & BBQ Festival Juneau Jazz & Classics Heritage Park TBA TBA Foley, Alabama Alabama International Dragway Juneau, Alaska 251.943.5590 2021Steele, Alabama 907.463.3378 www.foleybbqandblues.net www.bluesbikesbbqfestival.eventbrite.com jazzandclassics.org W.C. Handy Music Festival Johnny Shines Blues Festival Spenard Jazz Fest July 16-27, 2021 TBA TBA Florence, Alabama McAbee Activity Center Anchorage, Alaska 256.766.7642 Tuscaloosa, Alabama spenardjazzfest.org wchandymusicfestival.com 205.887.6859 23rd Annual Gulf Coast Ethnic & Heritage Jazz Black Belt Folk Roots Festival ARIZONA Festival TBA Chandler Jazz Festival July 30-August 1, 2021 Historic Greene County Courthouse Square Mobile, Alabama April 8-10, 2021 Eutaw, Alabama Chandler, Arizona 251.478.4027 205.372.0525 gcehjazzfest.org 480.782.2000 blackbeltfolkrootsfestival.weebly.com chandleraz.gov/special-events Spring Fling Cruise 2021 Alabama Blues Week October 3-10, 2021 Woodystock Blues Festival TBA May 8-9, 2021 Carnival Glory Cruise from New Orleans, Louisiana Tuscaloosa, Alabama to Montego Bay, Jamaica, Grand Cayman Islands, Davis Camp Park 205.752.6263 Bullhead City, Arizona and Cozumel, -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

A Progress Report on the Can-Do Playground at Milford Fall 2011 Donor Generosity Grows Can-Do Fund The generosity of eleven corporate and organizational donors has helped the Can-Do Playground at Milford fund grow toward its $800,000 goal. To date, gifts have been received from the following: • Draper Holding Charitable Foundation, Inc. • Delaware Foundation Reaching Citizens • MIlford Lions Club • Tidewater Utilities • Longwood Foundation • Trent Cole • Laffey-McHugh Foundation • Dr. Steven Alban • Garbutt Family Trust • Welfare Foundation Tidewater Utilities, Inc. recently presented a check for • Safeway Foundation $14,500 to the Can-Do Playground at Milford Steering Com- Thanks to the foresight and generosity of the City of mittee. This gift was made possible by proceeds raised dur- Milford and its Department of Parks and Recreation, the ing Tidewater’s 4th Annual Golf Tournament in August. playground already has a home in Silicato Park on Mil- Shown above are (front row, from left) Mike Kazala; Jerry ford’s Airport Road. This is a huge contribution towards the Esposito, President of Tidewater Utilities; Peggy Anderson; $800,000 estimated cost of the project.Once the funds for Dave Rutt, Can-Do Playground Chair; Joe Cuccinello and construction have been raised and the playground con- Liz Cuccinello; (back row, from left) George Anderson, Chip structed, the City will own and maintain it. Lank, Jack Donovan and Joe Wallace. Progress The need and a vision to fulfill it . Goal $800,000 Research shows that one in twenty persons will experience a disability during their lifetime. In southern Delaware, several thousand children who are not institu- 90% tionalized have some form of physical, cognitive, or sensory disability which limits their opportunity to use traditional playground equipment. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Shorezone Fish and Blue Crab Survey of Rehoboth Bay, Indian River Bay, and Little Assawoman Bay for 2018

Shorezone Fish and Blue Crab Survey of Rehoboth Bay, Indian River Bay, and Little Assawoman Bay For 2018 Andrew McGowan, and Dennis Bartow Delaware Center for the Inland Bays 39375 Inlet Rd Rehoboth Beach, DE 19971 September 2020 Report may be accessed via www.inlandbays.org © Delaware Center for the Inland Bays 2020 All Rights Reserved Citation Format McGowan, A.T., and D.H. Bartow. 2020. Shorezone fish and Blue Crab survey of Rehoboth Bay, Indian River and Bay and Little Assawoman Bay for 2018. Delaware Center for the Inland Bays, Rehoboth Beach, DE. 71 pp. Cover photo: Pinfish (Lagodon rhomboides), credit Dennis Bartow. The Delaware Center for the Inland Bays is a non-profit organization and a National Estuary Program. It was created to promote the wise use and enhancement of the Inland Bays watershed by conducting public outreach and education, developing and implementing restoration projects, encouraging scientific inquiry and sponsoring needed research, and establishing a long-term process for the protection and preservation of the Inland Bays watershed. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ iii Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 Methods and Materials ............................................................................................. -

Newark to Wilmington Trail Study July 2014

NEWARK TO WILMINGTON TRAIL STUDY JULY 2014 NEWARK TO WILMINGTON TRAIL STUDY NEWARK TO WILMINGTON TRAIL STUDY Prepared for the Delaware Department of Transportation, Division of Planning In association with Delaware State Parks and the Wilmington Area Planning Council Prepared by Whitman, Requardt & Associates, LLP Wilmington, Delaware July 2014 NEWARK TO WILMINGTON TRAIL STUDY CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Existing conditions .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Analysis process .................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Alignment descriptions ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Northern alignment ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Central alignment ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Southern alignment ....................................................................................................................................... -

2015 Report to Our Communities

NMRS-16-004_CBR_web_spreads_Layout 1 6/3/16 3:47 PM Page 1 Nemours /Alfred I. du Pont Ho spital for C hildren Nemours Biome dical Research Nemours Bri ghtSt art! Nemours Center for C hildre n’s Health Media Nemours Childre n’s Clinic Nemours Childre n’s Hos pital Nemours Children’s Prima ry Care Nemours Children’s Sp ecial ty Care Nemours Children’s Urgent Care Nemours du Pont Pediatrics Nemours E state Nemours Fund f or Childre n’s Health Nemours H ealth & Prevention Servic es Nemours Nat io nal O ffice of Poli cy & Preven tion Nemours Seni orCare Nemours. or g NemoursEdu cation.o rg Shared Guardia ns of KidsHealth.o rg Children’s Health & ReadingBrightSta rt.org JOY 2015 REPORT TO OUR COMMUNITIES ©2016. The Nemo urs Foundation. Nem ours is a register ed trade mark of The N emours Founda tion. NMRS-16-004_CBR_web_spreads_Layout 1 6/3/16 4:37 PM Page 3 Nemours is not simply a place for care, it’s a way of caring for children. TABLE OF CONTENTS Our promise, “to treat every child as if they were our own,” means we will do everything within our power to restore and improve the health of children. We are shared guardians of 1 A Message From David Bail ey 26 2015 Commun ity Benef it 4 Meeting Children and Families 29 Recognizing Our Voluntee rs children’s health and, by extension, their JOY. As one of the largest integrated pediatric health systems Where They Are 30 Celebrating the Joy of Giving in the United States we have the power to influence the places in which we provide care, as well as the 10 Creating a Joyful Environment 32 Stewards of Hea lt h and Joy 14 Finding More Meaning in ways in which we deliver services. -

Parks & Recreation Council

Parks & Recreation Council LOCATION: Deerfield Gulf Club 507 Thompson Station Road Newark, DE 19711 Thursday, May 4, 2017 9:30 a.m. Council Members Ron Mears, Chairperson Ron Breeding, Vice Chairperson Joe Smack Clyde Shipman Edith Mahoney Isaac Daniels Jim White Greg Johnson Staff Ray Bivens, Director Lea Dulin Matt Ritter Matt Chesser Greg Abbott Jamie Wagner Vinny Porcellini I. Introductions/Announcements A. Chairman Ron Mears called the Council meeting to order at 9:45 a.m. B. Recognition of Esther Knotts as “Employee of the Year”, Council wished Esther congratulations on a job well done and recognition that is deserved. C. Mentioned hearing Jim White on the WDEL radio. II. Official Business/Council Activities A. Approval of Meeting Minutes Ron Mears asked for Council approval of the February 2nd meeting minutes. Ron Breeding made a motion to approve the minutes. Clyde Shipman seconded the motion. The motion carried unanimously. B. Council Member Reports: 1. Fort Delaware Society – Edith Mahoney reported. Kids Fest is June 10th. The Society is working with the Division to provide activities and games. All activities are free but the Society will be selling water and pretzels. Beginning Memorial Day they begin their Outreach program with Mount Salem Church and Cemetery. The Society needs to begin fundraising. Edith asked if there is any staff that work in the Division who could provide “pointers” on fundraising. Dogus prints they would like to save, need cameras in the library and AV room, and need to replace carriage wheels on the island. They would like to get a grant to help cover the costs. -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Delaware - 10 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District KENT 2 - XXX A MCGINNIS POND ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $50,250.00 C 12/20/1966 12/20/1968 1 3 - XXX A KILLENS POND STATE PARK DIV. OF PARKS & RECREATION $251,515.00 C 8/19/1967 9/1/1968 1 7 - XXX A MILFORD NECK DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $115,450.00 C 4/22/1967 4/22/1969 1 8 - XXX A ANDREWS LAKE ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $10,562.50 C 4/20/1967 4/20/1969 1 10 - XXX A WOODLAND BEACH DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $11,000.00 C 4/3/1967 4/3/1969 1 11 - XXX A WOODLAND BEACH ACCESS DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $7,500.00 C 4/3/1967 4/3/1969 1 13 - XXX A LITTLE CREEK WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $33,000.00 C 5/25/1967 5/25/1969 1 14 - XXX A BLACKISTON WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $55,000.00 C 6/1/1967 6/1/1969 1 16 - XXX A BLACKISTON WILDLIFE AREA DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $101,250.00 C 6/2/1967 11/1/1967 1 20 - XXX A PETERSBURG-WRIGHT PROPERTY DIV. OF FISH & WILDLIFE $17,750.00 C 12/19/1967 12/19/1969 1 25 - XXX A PETERSBURG-RASH DIV. -

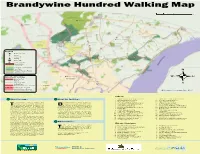

About the Facilities… About the Map… Find out More…

Brandywine Hundred Walking Map ◘Ramsey’s Farm Market ◘Highland Orchard & Market Legend Points of Interest School Historic Site T Parking Park & Ride ◘ Farmers Market Historic District Golf Course New Castle County Parkland State Park Woodlawn Trustees Property Shopping Center Little Italy Farmers Market Bike/Ped Facilities ◘ Hiking/Park Trail Sidewalk ◘Wilmington Farmers Market Planned Sidewalk Camp Fresh On Road Route ◘ Farmers Market Multi-Use Paved Trail or Bike Path ELSMERE Proposed Trail Connection Northern Delaware Greenway Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway © Delaware Greenways, Inc., 2009 About the map… About the facilities… 1 DARLEY ROAD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 17 CARRCROFT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 2 SPRINGER MIDDLE SCHOOL 18 A I DUPONT HIGH SCHOOL 3 TALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 19 SALESIANUM SCHOOL he Brandywine Hundred Walking Map randywine Hundred contains a fairly dense 4 MT PLEASANT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 20 ST EDMONDS ACADEMY illustrates some of the many opportunities network of sidewalks and connections. 5 CLAYMONT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 21 MT PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL for walking and bicycling throughout and In addition, many neighborhood streets T B 6 CHARLES BUSH SCHOOL 22 WILMINGTON FRIENDS UPPER SCHOOL around Brandywine Hundred. In addition, the and regional roads are suitable for walking and map highlights some of the area’s numerous bicycling, particularly those with wide shoulders. 7 LANCASHIRE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 23 BRANDYWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL recreational, cultural, and historical resources. However, not all sidewalks, connections, or road 8 TOWER HILL 24 HOLY ROSARY It is our hope that this map will assist you routes are indicated. 9 HANBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 25 CONCORD HIGH SCHOOL in finding local connections to these nearby This allows you to navigate off landmarks 10 CONCORD CHRISTIAN ACADEMY 26 ST HELENAS destinations and inspire you to enjoy the many and highlighted routes identified on the map.