Summary Report to the City of Milford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

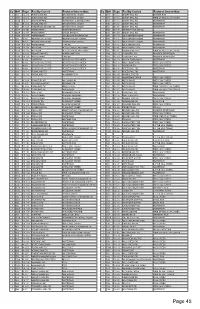

Bridge Index

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

151St General Assembly Legislative Guide 151St General Assembly Legislative Guide

151st General Assembly Legislative Guide 151st General Assembly Legislative Guide Senate – Table of Contents …………………………….…………………………...…….. i House of Representatives – Table of Contents ..….……………………..…….…...… ii General Assembly Email and Phone Directory ……………………………………..... iv Senate – Legislative Profiles ………………………………………………...………….... 1 House of Representatives – Legislative Profiles …..……………..……………….... 23 Delaware Cannabis Advocacy Network P.O. Box 1625 Dover, DE 19903 (302) 404-4208 [email protected] 151st General Assembly – Delaware State Senate DISTRICT AREA SENATOR PAGE District 1 Wilmington North Sarah McBride (D) 2 District 2 Wilmington East Darius Brown (D) 3 District 3 Wilmington West Elizabeth Lockman (D) 4 District 4 Greenville, Hockessin Laura Sturgeon (D) 5 Heatherbrooke, District 5 Kyle Evans Gay (D) 6 Talleyville District 6 Lewes Ernesto B. Lopez (R) 7 District 7 Elsmere Spiros Mantzavinos (D) 8 District 8 Newark David P. Sokola (D) 9 District 9 Stanton John Walsh (D) 10 District 10 Middletown Stephanie Hansen (D) 11 District 11 Newark Bryan Townsend (D) 12 District 12 New Castle Nicole Poore (D) 13 District 13 Wilmington Manor Marie Pinkney (D) 14 District 14 Smyrna Bruce C. Ennis (D) 15 District 15 Marydel David G. Lawson (D) 16 District 16 Dover South Colin R.J. Bonini (R) 17 District 17 Dover, Central Kent Trey Paradee (D) 18 District 18 Milford David L. Wilson (R) 19 District 19 Georgetown Brian Pettyjohn (R) 20 District 20 Ocean View Gerald W. Hocker (R) 21 District 21 Laurel Bryant L. Richardson (R) 22 151st General Assembly – Delaware House of Representatives DISTRICT AREA REPRESENTATIVE PAGE District 1 Wilmington North Nnamdi Chukquocha (D) 24 District 2 Wilmington East Stephanie T. Bolden (D) 25 District 3 Wilmington South Sherry Dorsey Walker (D) 26 District 4 Wilmington West Gerald L. -

Arc, and They Must Be, Under out Form of Government Especially, the Very Foundation of Social and Public Chilracter and Political Prosperity

112 arc, and they must be, under out form of government especially, the very foundation of social and public chilracter and political prosperity. The matter of inquiry intrusted to your committee ,is specific, and limi ted to the subject suggested in the resolution under which they were ap pointed. But were their duty more general, it would be impossible upon the pr.esent occasion, to point out the defects in the present system of free schools, and the errors. and imbecility in its administration-or to propose any. particular or partial changes 01• modification. To advance merely theoretical opinions as to a reformation, either in the principles or opera· tion of the system, would conduce to no beneficial or practical result. The subject is too vast to be grasped by the mind, without adequate and labo rious investigation. It would require the ptttient exercise of much research and reflection, to obtain a thorough 1,md available mastery of it, without which all suggestions must necessarily be but the crude theories of imper fect knowledge. That many arrors and imperfections exist, is almost uni. versally acknowledged;-and all men .will admit, that there is much room for improvement, if ngt an absolute necessity for entire and radical refor mation. Your committee believe that the matter of most pressing importance, is to institute a careful and comprehensive investigation into the actual and practical results of the present school system, since the period of its adop· tion. Without this, neither its real value, nor its evils and abu~es can be properly ascertained; and as the object of any change would be strict uti lity and the most economical mode of improvement, it is indispensably pre-requisite to begin in the proper ma,nner, and to.understand precisely what is the· disease which is to be remedied. -

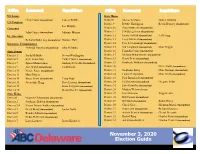

Informational Brochure

US Senate State House Chris Coons (incumbent) Lauren Witzke District8 Sherae’A Moore Daniel Zitofsky US Congress District 9 Debbie Harrington Kevin Hensley (incumbent) Lee Murphy Governor District 10 Sean Matthews (incumbent) John Carney (incumbent) Julianne Murray District 11 Jeff Spiegelman (incumbent) Lt. Governor District 12 Krista Griffith (incumbent) Jeff Cragg Bethany Hall-Long (incumbent) Donyale Hall District 13 Larry Mitchell (incumbent) Insurance Commissioner District 14 Pete Schwartzkopf (incumbent) Trinidad Navarro (incumbent) Julia Pillsbury District 15 Val Longhurst (incumbent) Mike Higgin State Senate District 16 Franklin Cooke (incumbent) District 1 Sarah McBride Steven Washington District 17 Melissa Minor-Brown (incumbent) District 5 Kyle Evans Gay Cathy Cloutier (incumbent) District 18 David Benz (incumbent) District 7 Spiros Mantzavinos Anthony Delcollo (incumbent) District 19 Kimberly Williams (incumbent) District 9 Jack Walsh (incumbent) Todd Ruckle District 20 Steve Smyk (incumbent) District 12 Nicole Poore (incumbent) District 21 Stephanie Barry Mike Ramone (incumbent) District 13 Mary Pinkey District 22 Luann D’Agostino Mike Smith (incumbent) District 14 Bruce Ennis (incumbent) Craig Pugh District 23 Paul Baumbach (incumbent) District 15 Jacqueline Hugg Dave Lawson (incumbent) District 24 Ed Osienski (incumbent) Gregory Wilps District 19 Brian Pettyjohn (incumbent) District 25 John Kowalko (incumbent) District 20 Gerald Hocker (incumbent) District 26 Madina Wilson-Anton State House District 27 Eric Morrison Tripp -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 03/28/2013 4:46:57 PM OMB NO

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 03/28/2013 4:46:57 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 u.s. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 02/28/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. DLA Piper LLP (US) 3712 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 500 8th Street NW Washington, DC 20004 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No • (2) Citizenship Yes • No D (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No 0 (2) Ownership or control Yes • No 0 (3) Branch offices Yes Q No H (c) Explain fully all changes, ifany, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No ED If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • NoD If no, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

2019 Monoblogue Accountability Project Delaware Edition

2019 monoblogue Accountability Project Delaware Edition A voting summary for the Delaware General Assembly ©2019 Michael Swartz. Reprint permission is granted with credit to “Michael Swartz at monoblogue” (with link) Introduction I began the monoblogue Accountability Project in 2008 to grade all 188 members of the Maryland General Assembly on whether they voted in what the author considered a conservative manner or not. But in 2017 I decided to add a Delaware edition which would grade the First State's 62 legislators in a similar manner to how I rated the Maryland General Assembly because I was working in the state at the time. After the 2018 session I retired the original Maryland edition, but since my wife and I have subsequently invested in Delaware through the purchase of our house I’m now making this Delaware edition an annual guide. Like my previous Delaware editions, I will do floor votes on 25 separate bills of interest that had both House and Senate votes. Legislators are listed in alphabetical order, which makes it easy to compile votes because the tally sheets are somewhat (as I'll explain later) alphabetical in Delaware. Thus far since the 2018 election there has not been turnover in the Delaware General Assembly so all are graded on 25 votes. The method to my madness The next portion of the monoblogue Accountability Project explains why votes are tabulated as they are. The first few pages will cover the bills I used for this year’s monoblogue Accountability Project and the rationale for my determining whether a vote is “right” or “wrong.” 25 floor votes are tallied, and there is a perfect possible score of 100 for getting all 25 votes correct: a correct vote is worth four points and an incorrect vote is worth none. -

Delawarehousejournal

r-A/~,·;,f);;;_?' /ha~] . ~~~- ·~ f . //W~~ . , f JOURNAL~4' /'lf7f ~«) 1 \ <b eHsE oF RE;.;;SENTA;; .• ,ES , ,c ' <., · OF TIU: ITATB OP DILAWARB, SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, COMMENCED ANO BEL!> AT DOVER, ON TUESDAY THE SECOND f:AY OF JANUARY, la the year of our Lord one Thousand l!llght Hundred arut''Jr9l'ty•nille • .Al'm OFT~ INDEPEN'DENCE. OF ·T~ 11.NITED STATES OF AMElUCA, Tll:E 8:BV:Bl\TTY•TECJ:B.D. WILMINGTON, ~EL.: EVANS AND VERNON, PRINTllS, 1849 . : ··: :-.-: ··: : : .......... .·.. ...... ... ••":. .. .... :. : ::: ·.... : .: .:: : . : ··~':r,·-.... 1;. • • • • • • • • •••••• :'\~/·• • • ..: • • , ..... ~ : . :.: ·.: . ~ ...· . : :: : : ... .. ., . .. .. .. .. ' I ·, .. .. ·. \ r ,,., ';.,.c, c: . \) ~\ou:i ?\'\ ,L "' ,:.,.'\ p·,, oct IC\·~::.· .J01JRNAJ.., OF TUE .Bouse of Representatives OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE. ,.lit a Se8si9n of the General .11.ssembly, convened and held at Dover, on ·Tuescl,ay, the second day of Janua~y, .in the year of our Lord one thouaand eight,hundred and forty-nine, and 9f .the Independence of the United States of .fl..merica, the seventy-third, · Messrir. Edward G. Bradford, Benjamin Caulk, Levi G. Cooch, Ed ~ T •. Bellah,James L. Miles, Thomas M. Rodney and Elias S. Nau dain, of New Castle County.; ~n\l · · Messrs. Daniel Cummins, Edwo,rd W. Wilson, Joseph P. Comegys, Paris T. Carlisle, Henry Taylor, James Postles and John A. Collms1 of Kent County; and ).\t:ess,:s. Samuel D. Vaughan, William Tunnell, John Marshall, Philip C. Jones, John Martin and Nathaniel Tunnell, of Sussex [C1)\;mt7, 5l;p .. peared and took their ;seats. · The foregoing members being all present, the returns of the election for Representatives of the several counties of the State were read. -

Cultural Contexts

3.0 CULTURAL CONTEXTS 3.0 CULTURAL CONTEXTS 3.1 PRE-COLONIAL PERIOD OVERVIEW The following brief, general discussion provides an outline of the prehistoric cultural record of the Delmarva Peninsula as it is currently understood (e.g., Custer 1984a, 1986a, 1987, 1989, 1994; Thomas et al. 1975). The prehistoric archeological record of the Delmarva Peninsula can be divided into five major periods: • the Paleoindian Period (circa 14,000 - 8,500 yrs. BP); • the Archaic Period (8,500 - 5,000 yrs. BP); • the Woodland I Period (5,000 - 1,000 yrs. BP); • the Woodland IT Period (1,000 - 350 yrs. BP; and • the Contact Period (A.D. 1650 - A.D. 1700). 3.1.1 PALEOINDlAN PERIOD Native Americans first inhabited Delaware sometime after 14,000 yrs. BP, based on dates from Paleoindian period sites in the eastern United States (Custer 1989:81-86). It is believed that small family groups of Paleoindians lived a wandering existence, hunting in the shifting woodland and grassland mosaic of the time. Game animals may have included musk ox, caribou, moose, and the extinct mastodon; however, modem game animals, such as white-tailed deer, were also present in the region (Custer 1989:95-98). Skeletal evidence of extinct megafauna (mastodon, mammoth) and large northern mammals (e.g., moose, caribou) has been recovered from the drowned continental shelves of the Middle Atlantic region (Emory 1966; Emory and Edwards 1966; Edwards and Merrill 1977). The Paleoindian stone tool kit was designed for hunting and processing animals. Wild plant foods supplemented the diet. Distinctive "fluted" points, characteristic of the early Paleoindian period, show a preference for high quality stone (Custer 1984b). -

Outline Descendant Report for Thomas Marvel Jr

Outline Descendant Report for Thomas Marvel Jr. 1 Thomas Marvel Jr. b: 11 Nov 1732 in Stepney Parish, Somerset County, Maryland, d: 15 Dec 1801 in Dover, Kent County, Delaware + Susannah Rodney b: 1742 in Sussex County, Delaware, m: Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1797 in Sussex County, Delaware ...2 Thomas Marvel III b: 08 Mar 1761, d: 1801 + Nancy Knowles b: 1765 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1820 in Sussex County, Delaware ......3 James W. Marvel b: 1780 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 13 Dec 1840 in Concord, Sussex, Delaware + Margaret Marvel b: 1781 in Broad Creek Hundred, Sussex, Delaware, m: 1808 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1850 in Seaford, Sussex County, Delaware .........4 Caldwell Windsor Marvel b: 21 Aug 1809, d: 15 Nov 1848 in Seaford, Sussex County, Delaware + Elizabeth Lynch b: 10 Apr 1807 in Sussex County, Delaware, m: 05 Jul 1837 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 10 Mar 1869 in Sussex County, Delaware ............5 William Thomas Marvel b: 12 Aug 1838 in Millsboro, Sussex, Delaware, d: 21 Jan 1914 in Lewes, Sussex County, Delaware + Mary Julia Carpenter b: 1842 in Delaware, m: 08 Sep 1861, d: 1880 ...............6 Ida F. Marvel b: Aug 1868 in Delaware + Frank J. Jones b: Feb 1867 in Virginia, m: 1891 ..................7 Anna W Jones b: Feb 1892 in Delaware ..................7 William A Jones b: Nov 1894 in Delaware ..................7 Alverta W Jones b: Dec 1898 in Delaware ..................7 James F Jones b: 1901 in Delaware ...............6 Charles H. Marvel b: 1873 in Delaware ...............6 William Thomas Marvel Jr. b: 22 Nov 1875 in Wilmington, Delaware, d: 17 Aug 1956 in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Age: 81 + Mary G Laubmeister b: Feb 1881 in Germany, m: 1900 in New Jersey ..................7 Margaret E Marvel b: 1902 in New Jersey, USA ..................7 Edward W Marvel b: 31 Oct 1904 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, d: 02 Jul 1963 in Cheltenham, Montgomery, Pennsylvania; Age: 58 + Mary G McMenamin b: Abt. -

Wetlands of Delaware

SE M3ER 985 U.s. - artm nt of h - n erior S ate of D lawa FiSh and Wildlife Service Department of Natural Resourc and Enviro mental Con ra I WETLANDS OF DELAWARE by Ralph W. Tiner, Jr. Regional Wetland Coordinator Habitat Resources U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 Newton Corner, MA 02158 SEPTEMBER 1985 Project Officer David L. Hardin Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Wetlands Section State of Delaware 89 Kings Highway Dover, DE 19903 Cooperative Publication U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Delaware Department of Natural Region 5 Resources and Environmental Habitat Resources Control One Gateway Center Division of Environmental Control Newton Corner, MA 02158 89 Kings Highway Dover, DE 19903 This report should be cited as follows: Tiner, R.W., Jr. 1985. Wetlands of Delaware. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wetlands Inventory, Newton Corner, MA and Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Wetlands Section, Dover, DE. Cooperative Publication. 77 pp. Acknowledgements Many individuals have contributed to the successful completion of the wetlands inventory in Delaware and to the preparation of this report. The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Wetlands Section contributed funds for wetland mapping and database construction and printed this report. David Hardin served as project officer for this work and offered invaluable assistance throughout the project, especially in coor dinating technical review of the draft report and during field investigations. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Philadelphia District also provided funds for map production. William Zinni and Anthony Davis performed wetland photo interpretation and quality control of draft maps, and reviewed portions of this report. -

North Atlantic Ocean

210 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 26 SEP 2021 75°W 74°30'W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 6 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml Trenton 75°30'W 12314 P ENNSYLV ANIA Philadelphia 40°N 12313 Camden E R I V R E R Wilmington A W A L E D NEW JERSEY 12312 SALEM RIVER CHESAPEAKE & DELAWARE CANAL 39°30'N 12304 12311 Atlantic City MAURICE RIVER DELAWARE BAY 39°N 12214 CAPE MAY INLET DELAWARE 12216 Lewes Cape Henlopen NORTH ATL ANTIC OCEAN INDIAN RIVER INLET 38°30'N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 6 ¢ 211 Delaware Bay (1) This chapter describes Delaware Bay and River and (10) Mileages shown in this chapter, such as Mile 0.9E their navigable tributaries and includes an explanation of and Mile 12W, are the nautical miles above the Delaware the Traffic Separation Scheme at the entrance to the bay. Capes (or “the Capes”), referring to a line from Cape May Major ports covered are Wilmington, Chester, Light to the tip of Cape Henlopen. The letters N, S, E, or Philadelphia, Camden and Trenton, with major facilities W, following the numbers, denote by compass points the at Delaware City, Deepwater Point and Marcus Hook. side of the river where each feature is located. Also described are Christina River, Salem River, and (11) The approaches to Delaware Bay have few off-lying Schuylkill River, the principal tributaries of Delaware dangers. River and other minor waterways, including Mispillion, (12) The 100-fathom curve is 50 to 75 miles off Delaware Maurice and Cohansey Rivers. -

Voting Edition 2020

AFFILIATED WITH THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION D.S.S.A. NEWS DELAWARE STATE SPORTSMEN’S ASSOCIATION A PUBLICATION OF THE DELAWARE STATE SPORTSMEN’S ASSOCIATION Visit us on the web: DSSA.us P.O. Box 94, Lincoln, DE 19960 • House District 26 Tim Conrad 2020 GENERAL ELECTION • House District 27 Tripp Keister • House District 28 Bill Carson The 2020 General Election here in Delaware is just • House District 29 Bill Bush about upon us. This is perhaps the most important • House District 30 Shannon Morris election of our time. Never before has our most basic • House District 31 Richard Harpster right to keep and bear arms been under attack and in • House District 32 Andrea Bennett danger of being eliminated. • It is vitally important that you vote and get your House District 33 Charles Postles family and friends to also vote. • House District 34 Lyndon Yearick This election edition of the DSSA newsletter contains • House District 35 Jesse Vanderwende the grades and endorsements for the upcoming • House District 36 Bryan Shupe November 3, 2020, elections here in Delaware, located at the end of the newsletter. The following information Please take the time to review the candidates and is provided as a service to our members and is designed get out and vote. It is also not too late to contribute to to provide our members with information as to how we their campaign. view each of the various candidates for public office in terms of their support for the rights of hunters, Elections Have Consequences sportsmen, shooters and gun owners with special focus By: John C.