The Presidio 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soldiers and Veterans Against the War

Vietnam Generation Volume 2 Number 1 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Article 1 Against the War 1-1990 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1990) "GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Against the War," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol2/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GI RESISTANCE: S o l d ie r s a n d V e t e r a n s AGAINST THE WAR Victim am Generation Vietnam Generation was founded in 1988 to promote and encourage interdisciplinary study of the Vietnam War era and the Vietnam War generation. The journal is published by Vietnam Generation, Inc., a nonprofit corporation devoted to promoting scholarship on recent history and contemporary issues. ViETNAM G en eratio n , In c . ViCE-pRESidENT PRESidENT SECRETARY, TREASURER Herman Beavers Kali Tal Cindy Fuchs Vietnam G eneration Te c HnIc a I A s s is t a n c e EdiTOR: Kali Tal Lawrence E. Hunter AdvisoRy BoARd NANCY ANISFIELD MICHAEL KLEIN RUTH ROSEN Champlain College University of Ulster UC Davis KEVIN BOWEN GABRIEL KOLKO WILLIAM J. SEARLE William Joiner Center York University Eastern Illinois University University of Massachusetts JACQUELINE LAWSON JAMES C. -

GI and Veterans' Movement Against the War, 1965-1975: a Selected Bibliography Skip Delano

Vietnam Generation Volume 2 Number 1 GI Resistance: Soldiers and Veterans Article 9 Against the War 1-1990 GI and Veterans' Movement Against the War, 1965-1975: A Selected Bibliography Skip Delano Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Delano, Skip (1990) "GI and Veterans' Movement Against the War, 1965-1975: A Selected Bibliography," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 2 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SeIectecI BiblioqRAphy Gl ANd Veterans' Movement AqaInst t U e War, 1 9 6 5 1 9 7 5 CoMpiUd by Skip DeIano, DECEMbER 1 9 8 9 How To Use This BiblioqRAphy This bibliography includes articles from newspapers, magazines, journals, and books. Many were published during the Vietnam war and are sources a historian might consult if he or she were writing about he antiwar movement of the 1960s. If you want to read more on a particular subject, begin your search under the topic heading you think most appropriate. Also skim through other topic headings for works which might relate to your subject. Some entires overlap these topic headings but are listed here only once. Take a few minutes to skim over the complete list. This bibliography emphasizes materials you will most likely have available in your local library. -

2018 Full Disclosure 50Th Anniversary Calendar

2018 Full Disclosure Vietnam W ar Commemorative Calendar (50th Anniversary of 1968 events) The battle for Hue (the former imperial Capital, located in central Vietnam) was the most contested battle (January 31- March 2) in the 1968 Tet offensive, widely considered to be the political turning point of the American war in Vietnam. Pictured is the National liberation Front (NLF) flaG placed on the Hue Citadel flaG tower on January 31. 1968 was a defining year in the American War in Vietnam and in US history. The Tet offensive turned the tide in the war; President Johnson decided not to run for a second term. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. GIs at Fort Hood and the Presidio took stands against the war, and campuses exploded with protest. For more information about these events, consult the Full Disclosure chronology at http://vietnamfulldisclosure.org/index.php/a-brief-chronology-of-vietnam-the-united- states-and-their- relations. The calendar is for 2018, but all entries, except for 2018 holidays which are iitalicized, are anniversaries of events from 1968. All Vietnam war-related entries are in bold. Apologies in advance for omissions due to lack of space and/or consciousness. January 2018 Northern nemesis: An NLF (South Vietnamese National Liberation Front) soldier takinG part in the Tet offensive, 1968 (Getty ImaGes / AGence France- Presse) Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 New Year’s Day. GIs threatened with Alexander Dubček Article 15 (non- succeeds Novotný judicial) as Communist punishment for leader of antiwar positions. Czechoslovakia. 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1st class US postage raised from 5 cents to 6 cents. -

This Is Yours

fern 1i-30<f hWà 111 IM i :J i w ISSUE NQI APRIL* bl FREE TO SI'S PUBLISHED UNDERGROUND-FOR AND BY GPS AT THE FORT ORD MILITARY COMPLEX iiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiitiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiQiiiiiiiiiii A NEWSPAPER FOR SERVICEMEN THIS IS YOURS NO ONE CAN TAKE TMS AWAY FfcOAA YOU Travel TOUR #1 Quick Action-packed 12 Month THIS COPY IS YOUR, PRIVATE PROPERTY Trip to the Exotic and Exciting EVEU âl'S HAVE CONSTITUTIONAL rUSHTS FAR EAST (VIETNAM) TOUR #2 13 months in Korea TOUR #3 Hawaii - Japan • Okinawa TOUR #4 Hunt and Fish in Alaska T'RniK/IN^ 1)-RV TOUR #5 Serve in the Sunny Caribbean ) s/ ALL EXPENSES PAID For full details see your unit travel agent (RE-ENLISTMENT NCO) FOR M one i Hf». f4ii s.f. £Z/-Z/VZ r-uptight the brass MAKE RESERVATIONSTODAY Work togefh IIMTERVIE FLASH!, EN MONTEREY!! ! ! Interview with Mrs. Trecethen mother of Ernest Trefethen one i inselinq Center will be of the Presidio 27 .beina tried »round May 1, 69 .in 1 for "MUTINY ;! ! ! '. Monterey. It's pur pose will be to counsel GI's What we.s your soi'» sent to the on C Lcations. To direct stockade .'or: A.WGL, was serv to Legal, suirttural and ing a 6 month sentence. nsychiatriatic del:, with-in the What was your reaction to tha area. This is a cooo orwuect news of the protest? Well I was with local groups, and S.c\ never informed ny the Artnv, X sroups sending down ...ull tinte read about, it. îri the newspaoer. counselors, clercrvmen, What is your opinion of your •ers. -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Keith Mather Keith Mather: Reminiscences of the Presidio 27 Presidio Trust Oral History Project The Presidio 27 Interviews conducted by Barbara Berglund Sokolov in 2018 Copyright © 2021 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley ii Since 1953 the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Keith Mather dated August 17, 2018. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Top of Page Interview Information

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard Millard Richard Millard: Judge Advocate for the Presidio 27 Presidio Trust Oral History Project The Presidio 27 Interview conducted by Barbara Berglund Sokolov in 2018 Copyright © 2020 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Richard Millard dated December 7, 2018. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. -

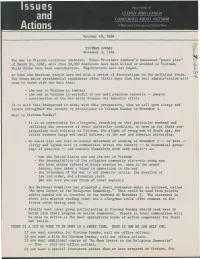

Issues Actions

Issues Newsletter of • CLERGY AND LAYMEN CONCERNED ABOUT VIETNAM Actions October 18, 1968 3 VIETNAM SUNDAY S November 3, 1968 The war in Vietnam continues unabated. Since President Johnson's announced "peace plan" of March 31, 1968, more than 30,000 Americans have been killed or wounded in Vietnam. Paris talks have been unproductive. Negotiations have not begun. V At home the American people have met with a series of frustrations on the political front. CP The three major presidential candidates offer little hope that the next administration will come to terms with the fact that: - the war in Vietnam is immoral - the war in Vietnam is wasteful of our most precious resource people - continuation of the war daily deepens our domestic crisis It is with this background in mind, with this perspective, that we call upon clergy and laymen throughout the country to participate in Vietnam Sunday on November 3. What is Vietnam Sunday? • It is an opportunity for clergymen, preaching on this particular weekend and utilizing the resources of their particular tradition, to open up for their con gregations such subjects as Vietnam, the plight of young men of draft age, the crisis between large and small nations, or the war and domestic priorities. • We would also ask that on Sunday afternoon or evening of November 3 — or both - clergy and laymen meet in communities across the country -- in ecumenical group ings if possible -- and concern themselves with such subjects as: - how the United States can end the war in Vietnam - the responsibility of the religious community vis-a-vis young men who have either refused military service or, once in the armed forces, have taken a stand in opposition to the war - the relevance of the war to our domestic crisis, the question of law and order, and alienated youth (We are sure you can think of other topics!) • Our National Committee has prepared a short statement which is enclosed, called "An Open Letter to the Religious Community." This could be read from pulpits and/or handed out in churches on the weekend of November 3. -

Revisiting the GI and Vietnam Veterans

Gudaitis, Alexandra 2019 History Thesis Title: “An Act of Honor”: Revisiting the GI and Vietnam Veterans Against the War Movements: Advisor: Jessica Chapman Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: N/A Contains Copyrighted Material: No “An Act of Honor”: Revisiting the GI and Vietnam Veterans Against the War Movements by Alexandra A. Gudaitis Jessica Chapman, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts April 15, 2019 Dedicated to the brave participants in the GI and Vietnam Veterans Against the War Movements, especially those who shared their stories with me. Table of Contents Acknowledgments.....................................................................................................................i Introduction: “We Have to Tell People the Truth”.........................................................................................1 Chapter One: “Acts of Conscience”: The GI Movement of the Vietnam War..............................................17 Chapter Two: “The Highest Form of Patriotism”: Vietnam Veterans Against the War................................55 Conclusion: “I Have No Regrets”................................................................................................................99 Images.....................................................................................................................................107 -

190814 Cortright Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae David Cortright Director of Policy Studies and the Peace Accords Matrix Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies Special Adviser for Policy Studies, Keough School of Global Affairs 1110 C Jenkins-Nanovic Hall University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556 Phone: 574.631.8536 Fax: 574.631.6973 Email: [email protected] Blog : davidcortright.net Chair of the Board of Directors Fourth Freedom Forum Goshen, Indiana EDUCATION • Ph.D., Political Science, Union Graduate School (The Union Institute), 1975 Washington, D.C. • M.A., History, New York University, New York, NY 1970 • B.A., History, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 1968 EMPLOYMENT • Director of the Peace Accords Matrix, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 2016- Present • Director of Policy Studies, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 2009- Present • Special Adviser for Policy Studies, Keough School of Global Affairs, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 2015-Present • Interim Co-Director, and Associate Director of Programs and Policy 2014-2015 Studies, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN • Research Fellow, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, 1989-2009 University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN • President, Fourth Freedom Forum, Goshen, IN 1992–2009 • Co-Director, SANE/Freeze, Washington, D.C. 1987–1988 • Executive Director, SANE, Washington, D.C. 1978–1988 • Research Associate, Center -

The Presidio Mutiny, 1968 - Randy Rowland

The Presidio mutiny, 1968 - Randy Rowland A personal account by a participant of the Presidio mutiny, a sitdown protest of soldiers in military prison against the killing of an inmate during the Vietnam war. 27 mutineers then faced the death penalty, which triggered national outrage. The San Francisco newspaper merely reported that a prisoner at the Presidio Stockade had been shot and killed by a guard. It was Friday, October 11th, 1968. Knowing that I would most likely end up in the stockade the next day, I was asked to investigate what was going on inside, and report it to the anti-war movement. Saturday a massive demonstration was to be held in San Francisco: "GIs and Vets march for peace." 10,000 or more people would march in the demo. Four of us, AWOL from the military, were to turn ourselves in to military authorities at the end of the march. The Brass, worried about the growing GI anti-war movement, tried to prevent active duty GIs from going to the demo through harassment and blatantly restricting whole units to base for the weekend. In spite of this, many GIs and vets marched in the demonstration. Afterwards there was a small ceremony at the gates to the Presidio Army Base and I stepped over the line, into the custody of the awaiting MPs. I had been on orders to go to Vietnam (a common unofficial punishment for having applied for noncombatant status). On the advice of my lawyer, I had gone AWOL to avoid shipment. I hadn't been on a military base in over 3 months. -

Gi Dissent During the Vietnam War by Derek W. Seidman Ba

THE UNQUIET AMERICANS: GI DISSENT DURING THE VIETNAM WAR BY DEREK W. SEIDMAN B.A., UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES, 2002 A.M., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2005 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Derek W. Seidman This dissertation by Derek W. Seidman is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date ____________ ______________________________ Robert O. Self, Director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ____________ ______________________________ Elliott J. Gorn, Reader Date ____________ ______________________________ Naoko Shibusawa, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ____________ _______________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Derek W. Seidman was born in St. Louis, Missouri on May 3, 1980 and grew up in Rochester, New York and San Francisco, California. He attended the University of California, Los Angeles, where he received a B.A. in History with a Minor in Political Science in 2002. He received an A.M. in History from Brown University in 2005. While at Brown, he specialized in the social, cultural and political history of the 20th Century United States, with an emphasis on social movements. His dissertation research was funded by Brown University, the Center for the United States and the Cold War at New York University, the Center for the History of Print Culture in Modern America at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Wisconsin Historical Society, and the Friends of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. -

An Army of the Willing: Fayette'nam, Soldier Dissent, And

An Army of the Willing: Fayette’Nam, Soldier Dissent, and the Untold Story of the All‐ Volunteer Force by Scovill Wannamaker Currin Jr. Department of History Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Adriane Lentz‐Smith ___________________________ Dirk Bonker ___________________________ Sarah Deutsch Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT An Army of the Willing: Fayette’Nam, Soldier Dissent, and the Untold Story of the All‐ Volunteer Force by Scovill Wannamaker Currin Jr. Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Adriane Lentz‐Smith ___________________________ Dirk Bonker ___________________________ Sarah Deutsch An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Scovill Wannamaker Currin Jr. 2015 Abstract Using Fort Bragg and Fayetteville, North Carolina, as a local case study, this dissertation examines the GI dissent movement during the Vietnam War and its profound impact on the ending of the draft and the establishment of the All‐Volunteer Force in 1973. I demonstrate that the US military consciously and methodically shifted from a conscripted force to the All‐Volunteer Force as a safeguard to ensure that dissent in the ranks never arose again as it had during the Vietnam War. This story speaks to profound questions regarding state power that are essential to making sense of our recent history.