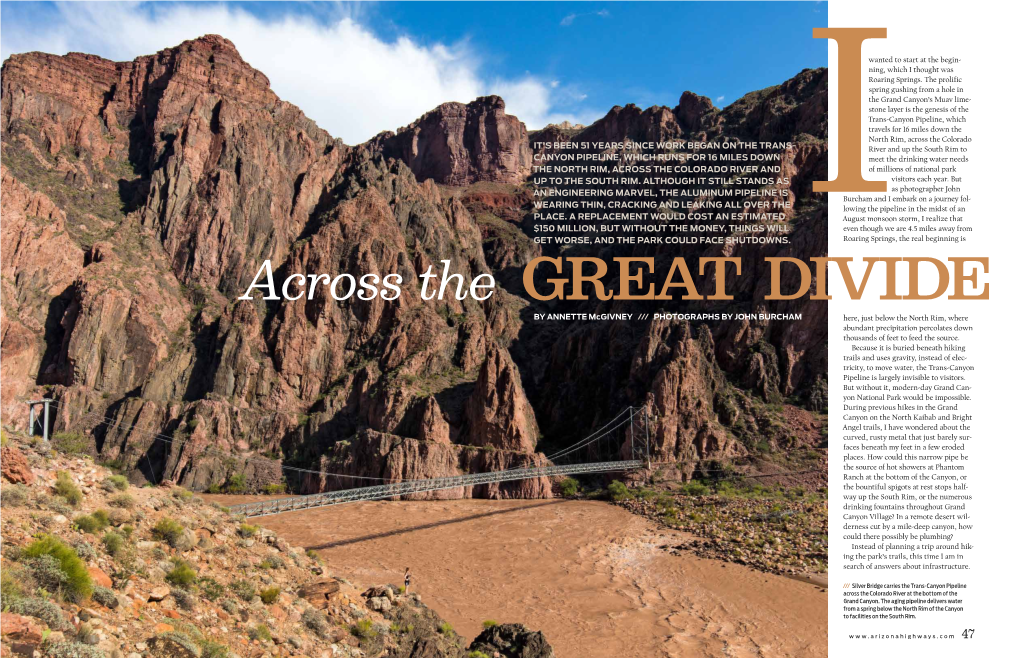

Across the GREAT DIVIDE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HHE Report No. HETA-99-0321-2873, U.S

NIOSH HEALTH HAZARD EVALUATION REPORT: HETA #99-0321-2873 U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona April 2002 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health PREFACE The Hazard Evaluations and Technical Assistance Branch (HETAB) of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducts field investigations of possible health hazards in the workplace. These investigations are conducted under the authority of Section 20(a)(6) of the Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA) Act of 1970, 29 U.S.C. 669(a)(6) which authorizes the Secretary of Health and Human Services, following a written request from any employer or authorized representative of employees, to determine whether any substance normally found in the place of employment has potentially toxic effects in such concentrations as used or found. HETAB also provides, upon request, technical and consultative assistance to Federal, State, and local agencies; labor; industry; and other groups or individuals to control occupational health hazards and to prevent related trauma and disease. Mention of company names or products does not constitute endorsement by NIOSH. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND AVAILABILITY OF REPORT This report was prepared by Ann Krake, Joel McCullough, and Brad King of HETAB, Division of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations and Field Studies (DSHEFS). Field assistance was provided by Loren Tapp. Desktop publishing was performed by David Butler. Review and preparation for printing were performed by Penny Arthur. The authors would like to thank Sergeant G. Douglas Fritts, United States Air Force, for his loan of the core body temperature monitors and Ms. -

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004

Grand Canyon March 18 – 22, 2004 Jeff and I left the Fruita-4 place at about 8 AM and tooled west on I-70 to exit 202 at UT-128 near Cisco, Utah. We drove south on UT-128 through the Colorado River canyons to US-191, just north of Moab. We turned south and drove through Moab on US-191 to US-163, past Bluff, Utah. US-163 veers southwest through Monument Valley into Arizona and the little town of Keyenta. At Keyenta we took US-160 west to US-89, then south to AZ-64. We drove west past the fairly spectacular canyons of the Little Colorado River and into the east entrance to Grand Canyon National Park. Jeff had a Parks Pass so we saved $20 and got in for free. Entry included the park information paper, The Guide, which included a park map that was especially detailed around the main tourist center: Grand Canyon Village. Near the village was our pre-hike destination, the Backcountry Office. We stopped at the office and got an update on the required shuttle to the trailhead. We read in The Guide that mule rides into the canyon would not begin until May 23, after we were done with our hike. Satisfied that we had the situation under control we skeedaddled on outta there on US-180, south to I-40 and Williams, Arizona. Jeff had tried his cell phone quite a few times on the trip from Fruita, but no signal. Finally the signal was strong enough in Williams. Jeff noted that Kent had called and returned the call. -

Introduction to Backcountry Hiking

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Hiking Into Grand Canyon Plan Ahead limits, and avoid spontaneity—Grand Canyon is an extreme Whether a day or overnight trip, hiking into Grand Canyon on environment and overexertion affects everybody at some point. the Bright Angel, North Kaibab, or South Kaibab trails gives an unparalleled experience that changes your perspective. Stay together, follow your plan, and know where you can call 911 with emergencies. Turning around may be your best decision. Knowledge, preparation, and a good plan are your keys to For information about Leave No Trace strategies, hiking tips, success. Be honest about your health and fitness, know your closures, roads, trails, and permits, visit go.nps.gov/grca- backcountry. Warning While Hiking BALANCE FOOD AND WATER Hiking to the river and back in one • Do not force fluids. Drink water when day is not recommended due to you are thirsty, and stop when you are long distance, extreme temperature quenched. Over-hydration may lead to a changes, and an approximately 5,000- life-threatening electrolyte disorder called foot (1,500 m) elevation change each hyponatremia. way. RESTORE YOUR ENERGY If you think you have the fitness and • Eat double your normal intake of expertise to attempt this extremely carbohydrates and salty foods. Calories strenuous hike, please seek the advice play an important role in regulating body of a park ranger at the Backcountry temperature, and hiking suppresses your Information Center. appetite. TAKE CARE OF YOUR BODY Know how to rescue yourself. -

North Kaibab Trail

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona North Kaibab Trail The North Kaibab Trail is the least visited but most difficult of the three maintained trails at Grand Canyon National Park. Almost a thousand feet higher at the trailhead than South Rim trails, hikers on the North Kaibab Trail pass through every ecosystem to be found between Canada and Mexico. At the rim, hikers will glimpse the vast maw of Bright Angel Canyon through fir trees and aspen, ferns and wildflowers. The trail as it descends through the Redwall Limestone is blasted directly into the cliff, "literally hewn from solid rock in half-tunnel sections." Farther down, the ecology progresses so that hikers look up at the surrounding canyon walls through a blend of riparian and desert vegetation. Along the way, Roaring Springs and Ribbon Falls both offer rewarding side trips that are wonderfully juxtaposed to the often hot conditions of the main trail. Built throughout the 1920s to match the quality and grade of the South Kaibab Trail, the present-day North Kaibab Trail replaced an older route infamous for crossing Bright Angel Creek 94 times (the present-day trail crosses only 6 times). Even though it is masterfully constructed and is a maintained trail, don't be deceived by the apparent ease and convenience of hiking it; from beginning to end, the North Kaibab Trail has its challenges. Locations/Elevations Mileages North Kaibab trailhead (8241 ft / 2512 m) to Supai Tunnel (6800 ft / 2073 m): 1.7 mi ( 2.5 km) Supai -

S 2

13 00 +J ^ .S 2 *c3 -3 - '£ w 2 S PQ <$ H Grand Canyon hiking is the reverse of moun tain climbing. First the descent, then the climb out, when one is tired — (exhausted). When you hike down into Grand Canyon you are entering a desert area where shade and water are scarce and where summer temperatures often exceed 41 C (105 F) and drop below freezing in winter. PLAN AHEAD! Allow at least 3 km (2 mi) per hour to descend and 21/2 km MVimi) per hour to ascend. ARE WE THERE YET ? ? DISTANCES: FROM BRIGHT ANGEL TRAILHEAD TO: Indian Gardens 7.4 km (4.6 mi) Colorado River 12.5 km (7.8 mi) Bright Angel Camp 14.9 km (9.3 mi) FROM SOUTH KAIBAB TRAILHEAD TO: Cedar Ridge 2.4 km (1.5 mi) Tonto Trail Junct. 7.1 km (4.4 mi) Bright Angel Camp 10.8 km (6.4 mi) FROM BRIGHT ANGEL CAMP AT RIVER TO: Ribbon Falls 9.3 km ( 5.8 mi) Cottonwood 11.7 km ( 7.3 mi) Roaring Springs 15.3 km ( 9.5 mi) North KaibabTrailhead 22.8 km (14.2 mi) FROM INDIAN GARDENS CAMP TO: Bright Angel Camp 7.5 km (4.7 mi) Plateau Point 2.4 km (1.5 mi) S. Kaibab Trail 6.6 km (4.1 mi) Junct. via Tonto Trail ELEVATIONS Bright Angel Lodge, South Rim 2091M (6860 ft) Yaki Point 2213M (7260 ft) Indian Gardens 1160M (3800 ft) Plateau Point 1150M (3760 ft) Bright Angel Camp 730M (2400 ft) Cottonwood 1220M (4000 ft) Roaring Springs 1580M (5200 ft) N. -

Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Page Title South Rim: May 24–September 7, 2009 Also Available in Deutsch, Español, Français, the Guide Italiano,

SPRING 2008 VISITOR’S GUIDE 1 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Page Title South Rim: May 24–September 7, 2009 Also available in Deutsch, Español, Français, The Guide Italiano, , NPS photo by Michael Quinn Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park Construction Ahead! Drive Cautiously. Look inside for The Grand Canyon we visit today is a gift from past generations. Take time to Road construction in the Mather Point – Canyon View Information Plaza area information on: enjoy this gift. Sit and watch the changing play of light and shadows. Wander continues throughout the summer. When the project is completed this fall, the Maps ............10–11,17,20 along a trail and feel the sunshine and wind on your face. Follow the antics of road will skirt the south side of Canyon View Information Plaza and additional Ranger Programs...........2–4 the ravens soaring above the rim. Can you hear the river roaring in the gorge far parking will provide easy access to the visitor center and rim. See additional below? We must ensure that future generations have the opportunity to form information on this project on page 9. Information Centers ......... 7 connections with this inspiring landscape. Drive slowly and obey all construction zone signs and flaggers. Sunrise & Sunset Times ....... 7 A few suggestions may make your visit more rewarding. The information in this Geology ................... 8 publication will answer many of your questions about the South Rim. Stop by Stop in One of the Visitor Centers Hiking..................16–17 a visitor center and talk with a ranger. -

North Rim 2005

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona North Rim: 2006 Season The Guide Also available in Français, Deutsch, Espan˜ ol, Italiano, Mountain Celebrate Life’s Diversity Standard Time The North Rim is a celebration of Fire is a key for healthy ponderosa the diversity of life found within pine forests. Low-intensity fires Grand Canyon National Park. The burn debris on the forest floor and lush, green meadows and forests return nutrients to forest soils pro- What Time Is It? of the Kaibab Plateau provide moting new growth. Evidence of Arizona remains on Mountain lessons on survival, renewal, and recent fires is visible on the North Standard Time (MST) year- solitude in wildness. Rim. In areas touched by fire, round. Daylight Savings Time is aspen seedlings push their way not observed, except on the The isolation of the North Rim through the darkened earth. The Navajo Reservation. has created a home for unique new growth attracts wildlife, and plants and animals. The shy the forest cycle continues. Kaibab squirrel, an example of evolutionary change through The highest elevations on the geographic isolation, is easily Kaibab Plateau, between 8,000 and identified by its charcoal-gray 9,100 feet (2,440–2,770 m), are body, distinct tufts of fur on the home to a community similar to tips of the ears, and its pure white the boreal forests of northern Meadows dot the Kaibab Plateau. NPS photo North Rim Map on tail. Its close relative, the Abert Canada. Spruce and fir found in page 8 squirrel, inhabits the South Rim this environment add to the diver- meadows thick with wildflowers an awe-inspiring view. -

Pocket Map South Rim Services Guide Grand Canyon

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Introduction to Backcountry Hiking Whether a day or overnight trip, hiking into Grand Canyon via Stay together, follow your plan, and know where and how to seek the Bright Angel, North Kaibab, or South Kaibab trails gives an help (call 911). Turning around may be the best decision. unparalleled experience that changes your perspective. For more information about Leave No Trace strategies, hiking Knowledge, preparation, and a good plan are all keys to tips, closures, roads, trails, and permits, visit go.nps.gov/grca- success. Be honest about your health and fitness, know your backcountry. limits, and avoid spontaneity—Grand Canyon is an extreme environment! Before You Go 10 Essentials for Your Day Pack • Each trail offers a unique opportunity to 1. WATER 6. SUN PROTECTION exprience Grand Canyon. Choose the Pack at least two liters of water depending Sunscreen, wide-brimmed hat, and appropropriate trail for your abilities. on hike intensity and duration. Always sunglasses. Consider walking the Rim Trail for an bring a water treatment method in case of easier experience. pipeline breaks or repair work. 7. COMMUNICATION Yelling, a whistle, signal mirrors, and cell • Check the weather forecast and adjust 2. FOOD phones—while service is limited, phones plans, especially to avoid summer heat. Salty snacks and high-calorie meal(s). can be helpful. Remember the weather can change suddenly. 3. FIRST AID KIT 8. EMERGENCY SHELTER A lightweight tarp provides shade and • Leave your itinerary with family or friends Include prescription medications, blister shelter. -

Hiking Along the North Rim North Rim Driving and Trail Guide

North Rim Driving and Trail Guide To Park Entrance il a To North Entrance Station To Kaibab National Forest Walhalla Ruins l A r North i and Scenic Drive T ncle Jim 0 2 Kilometers a r U T i k r and Jacob Lake Point Imperial r z c a Scale 0.5 Miles W T o i il id rss n tr KAIBAB PLATEAU fo a a 02Approximate scale Miles Walhalla T P 67 r n 0 1.0 km ail e Bourke Point Overlook K foreground area only 2.6mi (4.2km) 8803ft 2684m 6542ft 1995m A Cliff rail r Spring Bridle T THE BASIN i z o Trail To Point Sublime n a 5.4mi (8.7km) “Y” Administration 17.8mi (28.6km) ROARINGN SPRINGS CANYO Angels Window & Backcountry o Trail r Four-wheel drive Office t h Patrick Cape Royal Trail Greenland TRANSEPT CANYON K or high-clearance T 8480ft N a rail Ken Lake YO i CapeN Royal b vehicles recommended. Unpaved roads 2585m A Amphitheater a 7685ft C / 2343m b AP Vista Encantada E T may be impassable W r N KO a AN i O when wet. Uncle Jim N l k Tritle Y e N Trail re 14.5mi (23.3km) Peak A C General C l d Bridle T Store To Cottonwood Trail e Roosevelt Point Atoko Point n g n u Campground 8400ft T A o E Widforss t 2561m r and Phantom L h g rail R Uncle Jim Point g Ranch T North Rim O ri p U A 8336 ft B m O R 2541 m a N NorthIN C G Legend Transept Trail S P T R Trail described below r IN a North Rim K G n a S s i C Bicycle trail e Visitor Center b A N p WALHALLA PLATEAU a N O Drinking water t Bright b Y 8255ft O Y T Trail N N r 2516m Angel Emergency services a A il Point C W North Food service Oza Butte A L Gas station Widforss Point 8066ft H A Tiyo Point Roaring Springs -

Commercial Backpacking/Day Hiking/Transit Official Use Only 2

Form 10-115 Rev. 11/15/2016 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park Park Contact: Permits Coordinator, [email protected] Phone Number: 928-638-7707 COMMERCIAL USE AUTHORIZATION UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF P.L. 105-391 Section 418, (54 U.S.C. 101925) 1. AUTHORIZED ACTIVITY: Permit Number: CUA GRCA 5600 ____ Commercial Backpacking/Day Hiking/Transit Official Use Only 2. Authorization Holder Information Authorization: Begins:_______________ (Type information below) Official Use Only CONTACT NAME (Owner or Authorized Agent) Authorization Expires: December 31, 2020 ORGANIZATION/COMPANY EMAIL ADDRESS MAILING ADDRESS US DOT # CITY;STATE;ZIP TELEPHONE NUMBER/ FAX NUMBER 3. The holder is hereby authorized to use the following described land or facilities in the above named area (area must be restored to its original condition at the end of the authorization): Areas within Grand Canyon National Park open to the general public as designated by the attached authorization conditions. 4. Summary of authorized activity: (see attached sheets for additional information and conditions) Commercial guided backpacking, day hiking, and associated transit within Grand Canyon National Park. ☒ Out- of- Park: The commercial services described above must originate and terminate outside of the boundaries of the park area. This permit does not authorize the holder to advertise, solicit business, collect fees, or sell any goods or services within the boundaries of the park area. ☐In-Park: The commercial service described above must originate and be provided solely within the boundaries of the park area 5. NEPA/NHPA Compliance: Internal Use Only ☐Categorical Exclusion ☐ EA/FONSI ☐ EIS ☐ Other Approved Plans 6. -

Hiking Brightangel Kaibab Trails

HIKING BRIGHTANGEL AND KAIBAB TRAILS DISTANCES FROM INDIAN GARDENS CAMPTO: FROM BRIGHT ANGEL TRAILHEAD TO: Bright Angel Camp 7.5 km 4.7 mi This publication was provided by Grand Canyon Natural Indian Gardens 7.4 km 4.6 mi Plateau Point 2.4 km 1.5 mi History Association at the request of, and for distribu Colorado River 12.5 km 7.8 mi South Kaibab Trail tion by, Grand Canyon National Park. Information con Bright Angel Camp 14.9 km 9.3 mi Junction via Tonto tained herein was approved by the Park. 2-88 Trail 6.6 km 4.1 mi FROM SOUTH KAIBAB TRAILHEAD TO: Colorado River 5 km 3.1 mi Cedar Ridge 2.4 km 1.5 mi Tonto Trail Junction 7.1km 4.4 mi ELEVATIONS: C°i0raudARive,V mu A a™ Bright Angel Lodge, Bright Angel Camp 10.3 km 6.4 m, South Rim 2091m 6860 ft Yaki Point 2213 m 7260 ft FROM COLORADO RIVER AND Indian Gardens 1160 m 3800 ft BRIGHT ANGELCAMPTO: Plateau Point 1152 m 3781ft Ribbon Falls 9.3 km 5.8 mi Bright Angel Camp 730 m 2400 ft Cottonwood 11.7 km 7.3 mi Cottonwood 1220 m 4000 ft Roaring Springs 15.3 km 9.5 mi Roaring Springs 1580 m 5200 ft North Kaibab Trailhead 22.8 km 14.2 mi North Kaibab Trailhead 2512 m 8241ft Grand Canyon National Park HOW TO OBTAIN BACKPACKING Mail or phone reservations may be made by BRIGHT ANGEL CAMPGROUND: Camp PRECIPITATION: Most of the rain falls from PERMITS AND RESERVATIONS contacting: ing, water, tables, restrooms and ranger station July through September. -

NR 2011.Indd

LOOK INSIDE THIS GUIDE 2011 Season Look Inside 2 Plan Your Visit 5 Ranger-Led Programs 8 Park Map and Trail Guides 12 Hiking Information 14 Services Many More Answers to Your Questions... ...Look Inside North Rim Drive with care What Time Is It? Emergency: 911 • Observe posted speed limits. Most of Arizona, including Grand Canyon 24 hours-a-day dial • Maximum speed limit is 45 mph. National Park, remains on Mountain Standard 911 from any phone • Watch for pedestrians and wildlife. Time year-round. Arizona is on the same time • Increase caution at night and during wet as California and Nevada, and one hour behind 9-911 from hotel phones conditions. Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. What to do and Where to go in Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Guide & Maps Grand Canyon National Park | North Rim Enjoy the North Rim Use this Guide to get the most out of your visit Personalize Your Grand Canyon Experience Welcome to There are many ways to experience Grand Canyon. Individual interests, available time, and weather can influence a the North Rim visit. Refer to the maps on pages 8-9 to locate the places mentioned below. Sitting atop the Kaibab Plateau 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400 - 2,750 Activity Comment m) above sea level with lush green Drop by the visitor center • Open 8:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. (9:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. after meadows surrounded by a mixed October 15) conifer forest sprinkled with white- • Talk with a ranger barked aspen, the North Rim is • Enjoy the interpretive exhibits an oasis in the desert.