April 17, 2017 David Keanu Sai, Ph.D. 1. the BRIEF 1.1. the First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICV20 A-Intro Stolt.Pub

Marcia Vexillum — vexillology and military marches Lars C. Stolt Vexillology and military music have many points in common. The military banners and colours being the visual signs in the battle field correspond to the audible signs repre- sented by the regimental calls and marches. The military marches have often established a connection with vexillological items as flags, banners and colours to the mutual advan- tage. Music instruments like bugles, trumpets and kettle drums are often provided with banners, and march titles often refer to flags and colours and their symbolic values. The internationally best known example of a march with flag connection is The Stars and Stripes forever. It was written by the American ‘march king’ John Philip Sousa, returning from Europe 1896 in the ship Teutonic. The march was born of home- sickness and conceived during Sousa's journey home. David Wallis Reeves, by Sousa called ‘The father of band music in America’, wrote in 1880 his Flag March, based on ‘The Star Spangled Banner’. Further American flag marches are Flag of America (George Rosenkrans), Flag of freedom (Frank Pan- ella), Flag of Victory (Paul Yoder), Under the Stars and Stripes (Frank H Losey) and Under One Flag (Annibale Buglione). The rich German march world presents many flag marches. The German ‘march king’ Hermann Ludwig Blankenburg offers several: Mit der Siegesbanner, Mit Parade- flaggen, Unter dem Friedensbanner, Unter Freudensfahnen, Unter Kaisers Fahnen, Unter Preussens Fahne and Unter siegenden Fahnen. Other German flag marches ema- nate from the well known composer Franz von Blon: Mit Standarten, Unter dem Sieges- banner and Flaggen-Marsch, the last mentioned having a title in the United States with another, more specific meaning: Under One Flag. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Uppsatsplan För Examensarbete 2011

Sjökaptensprogrammet Examensarbete, 15HP Handledare: Stefan Siwek Student: Per Svadling Datum: 2011-04-26 Utflaggning och omstrukturering. Sju verksamheter på sjöfartsintensiva Åland berättar om sina upplevelser. Teckning: Molly Linnéuniversitetet Sjöfartshögskolan i Kalmar Utbildningsprogram: Sjökaptensprogrammet Arbetets art: Examensarbete, 15 hp Titel: Utflaggning och omstrukturering Författare: Per Svadling Handledare: Stefan Siwek ABSTRAKT Det här arbetet handlar om utflaggning av handelsfartyg och konsekvenserna av det. Utflaggning är en metod som redare av fartyg använder för att vinna fördelar. Under annan flagg, byter fartyget juridisk hemvist och lyder då annat lands lagstiftning. Mot slutet av 2000-talets flaggades passagerarfartyg- och färjor i Östersjötrafik ut från den åländska flaggen till den svenska. Att flagga ut till Sverige tillhör inte vanligheterna, men särskilda omständigheter för den här traden har gjort det svenska registret intressant för fartygsredare. Främsta anledningen till utflaggning angavs vara valutaexponeringen mellan den svenska kronan och euron, men här finns även andra orsaker som till exempel EUs snusförbud. Undersökningen studerar detta åländska exempel ur olika infallsvinklar. Arbetets syfte är att undersöka om och hur människor upplevde att de påverkades av utflaggningarna. Resultatet visar, utifrån olika infallsvinklar, i vilken utsträckning ett samhälles förutsättningar kan förändras när rederier flaggar ut sina fartyg. Nyckelord: Utflaggning, omstrukturering, sjöfart, Åland Linnaeus University Kalmar Maritime Academy Degree course: Nautical Science Level: Diploma Thesis, 15 ETC Title: Flagging out and restructuring Author: Mr. Per Svadling Supervisor: Mr. Stefan Siwek ABSTRACT This paper concerns the flagging out of merchant navy vessels and its consequenses. Flagging out is method used by ship owners in order to gain advantages. Under a different flag, the vessel's legal residence become the subject of another country´s laws. -

The Vexilloid Tabloid #27, July 2010

Portland Flag Association Publication 1 Portland Flag Association “Free, and Worth Every Penny!” Issue 27 July 2010 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Let Your Flags Wave Let Your Flags Wave 1 By John Hood (1960) from France Most of you know that I maintain August 04- Cook Islands, New Zealand Flag Retirement Ceremony 2 a database of occasions to fly (P) Constitution Day (1965) Flags in the News 3 flags. I don’t pretend that it is August 05- Peace River, BC, Can. (F) Flag Adopted (1970) July 2010 Flutterings 4 absolute, but it is pretty thorough. August 06- Bolivia (P) Independence Day Next Meeting Announcement 5 Some dates can be argued, but none are without some prove- (1825) from Spain Flag Related Websites 5 nance. For example, Flag Day August 07- Larrakian Aboriginals, Aus. 6 (F) Flag First Flown (1996) Flag Quiz does not necessarily equate to August 08- West Linn, OR, USA (P) City our June 14th, but rather the day Incorporated (1913) that seems most important to the August 09- Singapore (P) Independence flag of that country. I have Day (1965) from Malaysia abridged the list drastically, taking August 10- Missouri, USA (P) Admission only one occasion per day for the Day (1821) next two months and trying not August 11- Chad (P) Independence Day to repeat locations. If you find (1960) from France any error, let me know—if you August 12- Sacramento, CA, USA (F) have the flags, fly them. Flag Adopted (1989) August 13- Central African Republic (P) Independence Day (1960) from France August 14- Pakistan (F) Independence Day (1947) from UK August 15- Asunción, Paraguay (P) Founding of the City (1537) August 16- Liechtenstein (P) Franz Josef II's Birthday (1906) August 17- Indonesia (P) Independence Day (1945) from Netherlands August 19- Bahrain (F) Flag Confirmed (P) Primary Holiday (F) Flag Day (1972) August 01- Switzerland (P) National “There is hopeful sym- August 20- Flag Society of Australia (P) Day (1291) Founding Day (1983) bolism in the fact that August 02- British Columbia, Can. -

Sixth Grade School Tours at the Hackett House

SIXTH GRADE SCHOOL TOURS AT THE HACKETT HOUSE Trollhattan, Sweden The presentation will cover timelines and historical informations as it fits: Performance Objective covered: Construct timelines of the historical era being studied S2C1PO3, Primary/Secondary resources S2C1PO5, Archeological research S2C1PO8, Impact of cultural and scientific contributions of ancient civilizations on later civilizations S2C2PO6, Medieval Kingdoms: S2C3PO2, Renaissance: S2C4PO1 GREETING: hej pronounced hay (hi) or god dag (good day) Language of Trollhattan: Swedish I. Location/Geography (S4C1PO4, S4C4PO2, PO3, PO4, S4C6PO1 A. Hemisphere/continent 1. Trollhattan is in the country of Sweden. 2. Sweden is on the continent of Europe in the northern hemisphere. 3. Sweden has a population of around 9.7 million. 4. Sweden is part of the Scandinavian peninsula along with Norway and Denmark. 5. Sweden has a much milder climate than other areas this far north due to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream. 6. In the northernmost areas of Sweden, the sun never rises above the horizon for about 2 months. 7. The population of Trollhattan is about 47,000. B. Influence of water on development and trade (S2C2PO3, S2C3PO6, S4C2PO2, S4C4PO4, S4C5PO3) 1. Trollhattan is located on the banks of river Gota. 2. The name Trollhattan comes from folklore. People believed that large trolls lived in the river Gota, and the islands in the river were the trolls’ hoods or “hattor.” 3. Hydroelectric power is produced with a dam on the Gota river. 4. The abundance of hydroelectric power influenced the growth of Trollhattan as an industrial city. II. Historical Perspective A. Vikings 1. -

The Nordic Cross Flag: Crusade and Conquest April 22, 2020 Show Transcript

Season 1, Episode 5: The Nordic Cross Flag: Crusade and Conquest April 22, 2020 Show Transcript Welcome back to another episode of Why the Flag?, the show that explores the stories behind the flags, and how these symbols impact our world, our histories, and ourselves. I’m Simon Mullin. On the last episode, we discussed the Y Ddraig Goch – the red dragon flag of Wales – and the deep historical and mythological origins of the red dragon on a green and white ground. We traveled back nearly 2,000 years to the Roman conquest of Britannia and the introduction of the dragon standard to the British Isles by the Iranian-Eastern European Sarmatian cavalry stationed at Hadrian’s Wall. We explored how the dragon was adopted by the Roman army as a standard, and after their withdrawal from Britannia, its mythological rise as the symbol of Uther Pendragon and King Arthur, and then its resurrection by Henry VII – whose 15th Century battle standard closely resembles the flag of Wales we see today. National mythology plays a significant role in shaping our identities and how we see ourselves as a community and as a people. And, as we found in episode 4, these mythologies are instrumental in shaping how we design and emotionally connect to our national flags. We’re going to continue this theme about the cross-section of history, mythology, and national identity on the episode today as we discuss the rise of the Nordic Cross, a symbol that shapes the flags of all eight Nordic and Scandinavian countries today, and rules over nearly 28 million citizens speaking 15 distinct languages. -

Attachment No. 2 DOMINION of the HAWAIIAN KINGDOM

UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL COMPLAINT AGAINST THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE ACTING GOVERNMENT OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM CONCERNING THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM Attachment no. 2 DOMINION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM Dominion of the Hawaiian Kingdom prepared for the United Nations' Security Council as an Attachment to the Complaint filed by the Hawaiian Kingdom against the United States of America, 05 July 2001. David Keanu Sai Agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom CONTENTS ITHE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM 1 Establishing a Constitutional form of Government 2 The Illegal Constitution of 1887 3 Hawaiian Domain 4 A Brief Overview of Hawaiian Land Tenure II HAWAIIAN KINGDOM STATEHOOD 1 Commercial Treaties and Conventions concluded between the Hawaiian Kingdom and other World Powers a Austria-Hungary b Belgium c Bremen d Denmark e France f Germany g Great Britain h Hamburg i Italy j Japan k Netherlands l Portugal m Russia n Samoa o Spain p Swiss Confederation q Sweden and Norway r United States of America s Universal Postal Union 2 Hawaiian Kingdom Neutrality III AMERICAN INTERVENTION 1 American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom of January 16, 1893 2 The Fake Revolution of January 17, 1893 3 U.S. Presidential Fact-Finding Investigation calls for Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government 4 The American Thesis 5 Illegality of the 1893 Revolution 6 Puppet Character of the Provisional Government 7 The Attitude of the International Community 8 Failed Revolutionists declare themselves the Republic of Hawaiçi 9 Second Annexation Attempt of 1897 10 Legal Evaluation IV SECOND AMERICAN OCCUPATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM 1 United States Municipal Law Erroneously Purports to Annex Hawaiian Islands in 1898 2 U.S. -

L 287 Official Journal

ISSN 1725-2555 Official Journal L 287 of the European Union Volume 50 English edition Legislation 1 November 2007 Contents I Acts adopted under the EC Treaty/Euratom Treaty whose publication is obligatory REGULATIONS Commission Regulation (EC) No 1286/2007 of 31 October 2007 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables ............................... 1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1287/2007 of 31 October 2007 fixing the import duties in the cereals sector applicable from 1 November 2007 ................................................... 3 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 1288/2007 of 31 October 2007 establishing a prohibition of fishing for haddock in EC waters of ICES zones Vb and VIa by vessels flying the flag of Spain 6 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 1289/2007 of 31 October 2007 establishing a prohibition of fishing for cod in Kattegat by vessels flying the flag of Sweden ............................... 8 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 1290/2007 of 31 October 2007 reopening the fishery for cod in Skagerrak by vessels flying the flag of Sweden .............................................. 10 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 1291/2007 of 31 October 2007 amending for the 88th time Council Regulation (EC) No 881/2002 imposing certain specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities associated with Usama bin Laden, the Al-Qaida network and the Taliban ................................................................................... 12 (Continued overleaf) 2 Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. EN The titles of all other acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. -

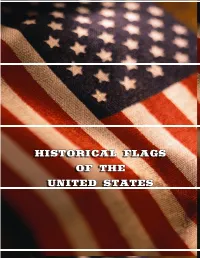

Flag Display Handout

HISTORICAL FLAGS OF THE UNITED STATES 1. The Royal Standard of Spain (1492) 2. The Personal Banner of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain (1492) 3. The Flag of France (1534) 4. The Flag of Sweden (1655) 5. The St. George Cross (1497) 6. The British Union Jack or King’s Color (1620) 7. The Queen Anne Flag, Red Ensign, or Meteor (1707) 8. The Bedford Flag (1737) 9. The Merchant Jack or Privateer Ensign or Son’s of Liberty Banner (1773) 10. The Culpepper Minute Men’s Flag (1775) 11. The Bunker Hill Flag (1775) 12. The Gadsden Flag (1776) 13. The Rhode Island Regiment Flag (1776) 14. The Grand Union or First Navy Ensign or Cambridge Flag (1776) 15. General Washington’s Headquarters Flag (1776) 16. The First Navy Jack (1776 and 2002) 17. The Bennington Flag or Spirit of ’76 (1776) 18. The Easton Flag, Easton Pennsylvania (1776) 19. The Fort Mifflin Flag, Delaware River (1777) 20. The First Official Flag of The United States of America (1777), Francis Hopkinson designer 21. The First Official Flag of The United States of America (1777), Betsy Ross version 22. The Flag of the Continental Navy Ship, Bon Homme Richard (1779) 23. The Gilford Court House Flag (1781) 24. The Philadelphia Light Horse Flag (1781) 25. The Second Flag, The Star Spangled Banner - 15 stars & 15 stripes (1795) 26. The Lewis and Clark Flag – 17 stars & 15 stripes (1804) 27. Don’t Give Up the Ship (1813) 28. The Third Flag – 20 stars & 13 stripes (1818) 29. The Sixth Flag – 24 stars (1822) 30. -

The Social Construction of Swedish Nature As a Touristic Attraction That Is the Focus of This Thesis

Department of Thematic Studies Environmental Change The Social Construction of Swedish Nature as a Touristic Attraction Emelie Fälton MSc Thesis (30 ECTS credits) Science for Sustainable development ISRN: LIU-TEMA/MPSSD-A- 16/005- -SE Linköpings universitet, SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Upphovsrätt Detta dokument hålls tillgängligt på Internet – eller dess framtida ersättare – från publiceringsdatum under förutsättning att inga extraordinära omständigheter upp- står. Tillgång till dokumentet innebär tillstånd för var och en att läsa, ladda ner, skriva ut enstaka kopior för enskilt bruk och att använda det oförändrat för icke- kommersiell forskning och för undervisning. Överföring av upphovsrätten vid en senare tidpunkt kan inte upphäva detta tillstånd. All annan användning av doku- mentet kräver upphovsmannens medgivande. För att garantera äktheten, säker- heten och tillgängligheten finns lösningar av teknisk och administrativ art. Upphovsmannens ideella rätt innefattar rätt att bli nämnd som upphovsman i den omfattning som god sed kräver vid användning av dokumentet på ovan be- skrivna sätt samt skydd mot att dokumentet ändras eller presenteras i sådan form eller i sådant sammanhang som är kränkande för upphovsmannens litterära eller konstnärliga anseende eller egenart. För ytterligare information om Linköping University Electronic Press se för- lagets hemsida http://www.ep.liu.se/. Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for non-commercial research and educational purpose. -

Official Journal L 154 Volume 46 of the European Union 21 June 2003

ISSN 1725-2555 Official Journal L 154 Volume 46 of the European Union 21 June 2003 English edition Legislation Contents I Acts whose publication is obligatory Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 on the establishment of a common classification of territorial units for statistics (NUTS) .......................................................................................... 1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1060/2003 of 20 June 2003 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables .................. 42 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1061/2003 of 20 June 2003 fixing the A1 and B export refunds for fruit and vegetables (tomatoes, oranges, table grapes and apples) ........ 44 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1062/2003 of 20 June 2003 setting the export refunds for nuts (shelled almonds, hazelnuts in shell, shelled hazelnuts and walnuts in shell) using system A1 ................................................................................................. 47 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1063/2003 of 20 June 2003 setting export refunds in the processed fruit and vegetable sector other than those granted on added sugar (provisionally preserved cherries, peeled tomatoes, sugar-preserved cherries, prepared hazelnuts, certain orange juices) ............................................................................ 49 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1064/2003 of 19 June 2003 prohibiting fishing for industrial fish by vessels flying the flag of Sweden ......................................... 51 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1065/2003 of 20 June 2003 on the opening of a standing invitation to tender for the resale on the internal market of some 7 425 tonnes of rice from the 2000 harvest held by the Spanish intervention agency ......................... 52 Commission Regulation (EC) No 1066/2003 of 20 June 2003 opening a standing invitation to tender for the export of sorghum held by the French intervention agency ... -

Bulletin of the European Communities Commission

ISSN 0378-3693 Bulletin of the European Communities Commission No 12 1989 Volume 22 The Bulletin of the European Communities reports on the activities of the Commission and the other Community institutions. lt is edited by the Secretariat-General of the Commission (rue de la Loi 200, B-1049 Brussels) and published 11 times a year (one issue covers July and August) in the official Community languages. The following reference system is used: the first digit indicates the part number, the second digit the chapter number and the subsequent digit or digits the point number. Citations should therefore read as follows: Bull. EC 1-1987, point 1.1.3 or 2.2.36. Supplements to the Bulletin are published in a separate series at irregular intervals. They contain official Commission material (e.g. communications to the Council, programmes, reports and pro- posals). • Notice to readers The next issue of the Bulletin, reporting on activities in January and February 1990, will be numbered 1 /2-1990. The presentation will be altered in an attempt to make it easier to consult. The intention is to enhance the Bulletin's value as a work of reference and publish it considerably quicker in all the official languages. © ECSC- EEC- EAEC, Brussels • Luxembourg, 1989 Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium Bulletin of the European Communities Commission ECSC- EEC- EAEC Commission of the European Communities Secretariat -General Brussels No 12 1989 Volume22 Sent to press in January 1990 Bulletin information service Readers