University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland a Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland A Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY PLANNING ORGANIZATION “A Forum for Communication and Discussion for a Vibrant Community” Home of the “North American Bigfoot Center” P. O. Box 363 Boring, Orygun 97009 Michael Fitz, Chair DAYTIME TELEPHONE: 503-502-5837 EMAIL: [email protected] www.boringcpo.org NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING 1 JUNE 2021 at 7:01 PM AT THE Boring Grange On SE Grange St MEETING AGENDA MEET AND GREET, AROUND 6:00 PM CHANGE TO THE MEETING: WE ARE STREAMING THE MEETING FROM OUR FACEBOOK PAGE. IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS ON STREAMING PLEASE DIRECT THEM TO STEVE BATES, YOU WILL GET WAY BETTER ANSWERS THAN ASKING ME. 1. Meeting called to order, flag salute self introductions and a little trivia, statistics on what the average citizen knows, by source. 2. Reports and advisements: A. Boring Water District B. Boring Oregon Foundation C. Boring-Damascus Grange D. Mt. Hood Center (Old Boring Equestrian Center) Liz Delmatoff the Learning Collective education administrator will have answers to your questions on the full time equestrian learning center and how it relates to the school system, charter schools and home schooling. 4. A moment of Boring History presented by Bruce Haney Bruce’s new book is out, on sale in several places around the county and I have read it. Well written and a very enjoyable read, I don’t know what he will have tonight but I know that it is never a boring minute. 5. Minutes of the previous meeting. 6. Treasurers report. 7. Land use issues: A. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Michael Arnold: All Right

Michael Arnold: All right. Welcome to episode three, Monday state of mind. My name is Michael Arnold. I am the director of alumni and recovery support services for the harmony foundation. On this episode, we are going to continue talking about the stories we tell ourselves. So if you're driving, you're just waking up. Maybe you're headed to the gym or out on that morning walk, or just getting your day going. You're going to want to make sure to have a pen and a piece of paper, or you're just going to have to put this episode on repeat because the guests that I have today, she's going to drop some serious knowledge bombs on the stories we tell ourselves. So do you guys want to know who this guest is? Her name is LauraBeth Burkhalter. LB. Do you want to tell everybody a little bit of, just give everybody a little bit of backstory about who you are, what you do? LB: Good morning guys. I'm LB. I am a person in recovery and I grew up in a little town called Natchez Mississippi. I'm currently the Director of. Community Engagement for Jade Recovery in Lakewood, Colorado. And I'm super stoked that Michael asked me to be on this podcast today because if there's one thing I know about it's stories and what I used to tell myself, Michael Arnold: Right. You know, that's, I was really excited to be able to start this podcast series out. -

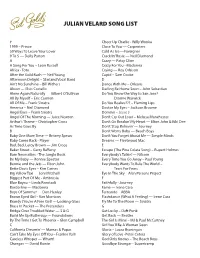

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Real Stories of East LA L.A

Real Stories of East LA L.A. Poet Laureate Holding Out Winner of FRANCO AGUILAR LUIS J. RODRIGUEZ for Lady Luck by 6-Word-Story looks for ghosts on police brutality JOSEPH MATTSON contest in southern Mexico Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 Poetry Editors Gustavo Mateo, Nils Rabe Fiction Editors Joshua Inglada, Daniel Sosa Layout Board Alena Morales, Marcille Sanguino Business Manager Kevin Rocha Proofreader Extraordinaire Joshua Castro Staff Joanna Alvarado, Lucy Alvarez, Joshua Castro, Joshua Inglada, Gustavo Mateo, Alena Morales, Robert Perez, Nils Rabe, Kevin Rocha, Marcille Sanguino, Daniel Sosa Faculty Editor Dustin Lehren Concept Design Diana Chang Layout and Design Production Yegor Hovakimian Milestone Committee Joan Goldsmith Gurfield, Dolores Carlos, Alexis Solis, Susan Suntree Cover Art Front cover: Photograph Franco Aguilar, What Lies There (Hacienda Photo Essay) Back cover: Oil on printed photograph Franco Aguilar & Jesus Barrales, Out of the Smoke Inside cover: Digital Photograph Jemima Wyman, Sample from fabric archive Milestone is published annually by the East Los Angeles College English Department, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park, California 91754. U.S. Submission Guidelines: The editors invite digital submissions of poetry, fiction/non-fiction, comics, essays of literary interest, art, and photography. Guidelines at milestone.submittable.com 2 Contents Introduction . 5 Acknowledgments . 7 Amarillas | Joseph Hernandez . 8 This, My Father Talk- | Andrew Liu . 13 From The Municipal Gardens | Andrew Liu . 14 Sea Layers | Joshua Inglada . 16 My Main Conflict | Michael Guerra . 17 a + d + d + i + n + g | Joshua Castro . 18 #collegestudentproblems | Raul Meza . -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts. -

Ending the Secrecy Part 1: I Survived This Thing

Living Bridges Project Transcript Ending the Secrecy - Ending the Secrecy Part 1: I Survived This Thing [Music] VOICEOVER: The following audio is part of the Living Bridges Project, an anonymous story-collecting project documenting responses to child sexual abuse. For more, please visit LivingBridgesProject.com. [Music] STORYTELLER: I think I’ll begin the story by thinking about the very first time that I even – that I realized that I was a survivor of child sexual abuse. It was – I was at community college and taking a psychology course and the conversation at the moment at that class was about suppressed memories. And we talked about what suppressed memories were and at one point the professor gave us a sheet – almost like a check-off sheet to say if you check off more than, I guess, five of these things then maybe you should go speak to a counselor or a therapist because it might be – you might be dealing with some repressed memories. And I remember looking at the sheet and marking almost all of them on the sheet and I was a little confused by that. I think the second part of the class was watching videos of families trying to deal with and address child sexual abuse after it happened within the family. So, in particular it was about a father who had abused the daughter and the family trying to stay together in spite of the abuse. At one point in the class I remember feeling completely overwhelmed and, now knowing – looking back now I know I was having an anxiety attack, but I didn’t know then. -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

“Is It Me? Am I Losing My Mind?” Living with Intimate Male Partners

“Is It Me? Am I Losing My Mind?” Living with Intimate Male Partners Presenting With Subjective Narcissistic Behaviours and Attitudes by Sherry Lynn Saunders Lane A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION Department of Educational Administration, Foundations and Psychology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2020 Sherry Lynn Saunders Lane Abstract Mainstream culture and the media are increasingly using the terminology 'narcissism' as socio- cultural parlance to describe selfish and self-centered behaviors and attitudes in social relationships. The purpose of this phenomenological research study is to describe the lived experience of women who are in intimate relationships with male partners whom they characterize as having narcissistic behaviors and attitudes. The research focus is motivated by client-centered therapeutic orientations that encourage counselors to 'be present with' clients, even when the experiences lack objective validation. Unstructured interviews were used to collect data from three adult females. The data was analyzed using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis approach. The participants' stories indicated that their relationships have identifiable phases and characteristics. The participants experienced diminished well-being, compromised self-differentiation, and pervasive loss. Pervasive loss served as a wake-up call and motivated the activation of participants’ residual sense of self to leave the relationships. In conclusion, while the terminology used to describe the intimate male partners may lack validation, the women perceive that their experiences negatively affected their lives. The women also recognized and regretted their lack of capability to negotiate dignified positioning in their intimate relationships. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Statement of Rafael Antonio Perez, Taken at the Metro

3/25/2020 www.pcaclaw.org/PEREZ002.html STATEMENT OF RAFAEL ANTONIO PEREZ, TAKEN AT THE METRO TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY (MTA) BUILDING, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA. IN RE: CASE NO. BA109900 People vs. Rafael Antonio Perez APPEARANCES BY: Richard Rosenthal Deputy District Attorney Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office Special Investigations Division 210 West Temple Street 17th Floor Los Angeles, California 90012 Luis F. Segura Sergeant Los Angeles Police Department Internal Affairs Group 304 S. Broadway #310 Los Angeles, California 90013 Michael Hohan Detective Los Angeles Police Department Robbery/Homicide Task Force 1 Gateway Plaza Los Angeles, California 90012 Winston Kevin McKesson Attorney at Law 315 S. Beverly Drive Suite 305 Beverly Hills, California 90212-4309 REPORTED BY: Sara A. Mahan Stenographic Reporter Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office sam/99-031 www.pcaclaw.org/PEREZ002.html 1/144 3/25/2020 www.pcaclaw.org/PEREZ002.html LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA, SEPTEMBER 17, 1999; 10:40 A.M. (On the record at 10:40 a.m.) (Oath was given by reporter.) THE WITNESS: I do. RAFAEL ANTONIO PEREZ, duly sworn and called as a witness, testified as follows: EXAMINATION BY DETECTIVE SEGURA: Q Okay. We're on the record. It's, uh, -- uhm, September 17th, 1999, 10:40 in the hours. Uh, we're interviewing, uh, Ray Perez. Present with him is his attorney Mr. Kevin McKesson. Uhm, also present is Detective Mike Hohan; myself, uh, Sgt. Segura; and, uh, Officer, uh, Jeff Pailet. And -- MR. PAILET: P-a-i-l-e-t. SGT. SEGURA: And the court, uh -- and the court reporter.