China and Methodism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missionary Advocate

MISSIONARY ADVOCATE. HIS DOMINION SHALL BE FROM SEA EVEN TO SEA, AND FROM THE RIVER EVEN TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH. VOLUME XL NEW-YORK, JANUARY, 1856. NUMBER 10. THB “ ROTAL PALACE ” AT OFIN. IN THE IJEBU COUNTRY. AFRICA. in distant lands, and direct their attention to the little JAPAN. gardens which here and there have been fenced in from A it a rriva l at San Francisco, of a gentleman who Above is presented a sketch taken in the Ijebu country, the wilderness. But it will not do always to dwell on went out from that port to Japan on a trading expedi an African district on the Bight of Benin, lying to the these, lest in what haB been done we forget all that re tion, affords the following information:— southwest of Egba, where the missionaries arc at work. mains to be done. We must betimes look from these In Egba they have several stations—at Abbeokuta, and pleasant spots to the dreary wastes beyond, that, re The religion of this country is as strange as the people Ibadan, and Ijaye, &e.; but into Ijebu they are only be themselves. Our short stay here has not afforded us minded of the misery of millions to whom as yet no much opportunity to become conversant with all their ginning to find entrance. It is much to be desired that missionaries have been sen’t, we may redouble our vocations and religious opinions. So far as I know of the Gospel of Christ should be introduced among the efforts, and haste to the help of those who are perishing them I will write you. -

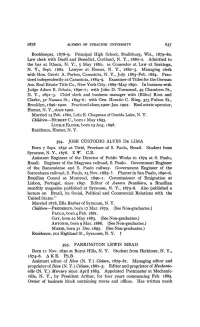

ALUMNI of SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY Bookkeeper, I878--9

ALUMNI OF SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY Bookkeeper, I878--9. Principal High School, Shullsburg, Wis., I879-80. Law clerk with Duell and Benedict, Cortland, N. Y., I88<>-2. Admitted to the bar at Ithaca, N. Y., 5 May I882; as Counselor at Law at Saratoga, N. Y., Sept. I882. Lawyer at Homer, N. Y., I882-3. Managing clerk with Hon. Gerrit A. Forbes, Canastota, N. Y., July I883-Feb. I884. Prac ticed independently at Canastota, I 884--9. Examiner of Titles for the German Am. Real Estate Title Co., New York City, I889-May I890. In business with Judge Adam E. Schatz, I89o-I; with John D. Townsend, 49 Chambers St., N. Y., I89I-3. Chief clerk and business manager with (Elihu) Root and Clarke, 32 Nassau St., I893-<i; with Gen. Horatio C. King, 375 Fulton St., Brooklyn, I 896--I 900. Practiced alone, I9oo-Jan. I 902. Real estate operator, Homer, N.Y., since I902. Married IS Feb. I882, Lulu E. Chapman of Oneida Lake, N.Y. Children-HUBERT C., born I May I893· LUCILE ELOISE, born 23 Aug. I898. Residence, Homer, N.Y. 394· JOSE CUSTODIO ALVES DE LIMA Born 7 Sept. I852 at Tiete, Province of S. Paulo, Brazil. Student from Syracuse, N.Y., I878. Z 'Y. C.E. 4\.ssistant Engineer of the Director of Public Works in I879 at S. Paulo, Brazil. Engineer of the Magyana railroad, S. Paulo. Government Engineer of the Bananalense and S. Paulo railway. Government Engineer of the Sorocabann railro~d, S. Paulo, 25 Nov. I88s-?. Planter in San Paulo, I89o-{). Brazilian Consul at Montreal, I89Q-I. -

Christian History & Biography

Issue 98: Christianity in China As for Me and My House The house-church movement survived persecution and created a surge of Christian growth across China. Tony Lambert On the eve of the Communist victory in 1949, there were around one million Protestants (of all denominations) in China. In 2007, even the most conservative official polls reported 40 million, and these do not take into account the millions of secret Christians in the Communist Party and the government. What accounts for this astounding growth? Many observers point to the role of Chinese house churches. The house-church movement began in the pre-1949 missionary era. New converts—especially in evangelical missions like the China Inland Mission and the Christian & Missionary Alliance—would often meet in homes. Also, the rapidly growing independent churches, such as the True Jesus Church, the Little Flock, and the Jesus Family, stressed lay ministry and evangelism. The Little Flock had no pastors, relying on every "brother" to lead ministry, and attracted many educated city people and students who were dissatisfied with the traditional foreign missions and denominations. The Jesus Family practiced communal living and attracted the rural poor. These independent churches were uniquely placed to survive, and eventually flourish, in the new, strictly-controlled environment. In the early 1950s, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement eliminated denominations and created a stifling political control over the dwindling churches. Many believers quietly began to pull out of this system. -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

Welcoming the Stranger PDF Presenter Notes

Slide 1 Welcoming the Stranger United Methodism’s Legacy of Embracing Diversity General Commission on Archives and History The United Methodist Church Heritage Sunday 2015 WNET, the PBS television station in New York City, recently stated “NYC today is one- third first generation immigrants with approximately 800 different languages spoken throughout the city.” United Methodism’s history of welcoming the stranger is just as important as it was in John Wesley’s day. Today’s cross-cultural welcoming is more difficult and nuanced which requires patience and understanding. By looking back at how United Methodism welcomed strangers into its fellowship and community can inform how The United Methodist Church can continue to be open to all peoples through the grace of God. Photograph caption - Immigrants looking at Statue of Liberty from Battery - NYC. From the Mission Album Collection – Cities 5 (http://catalog.gcah.org/omeka/collections/show/39). All citations in the above format are from the General Commission on Archives and History holdings located in Madison, New Jersey (http://catalog.gcah.org:8080/exist/publicarchives/gcahcat.xql?query=). Slide 2 Who is the Stranger? The stranger can be anyone. A stranger can range from a family member to groups of people whose ways seem different than your own. Nationalities, customs, norms, mores, living patterns, addiction, ethnicity, physical handicaps, politics, identity, economics, religious expression, history, addiction, as well as other factors create distrust, hatred, racism, sexism, prejudice, violence, etc. Photograph of the 2nd Avenue entrance to the Methodist Episcopal Church of All Nations in New York City. Here is an example of a store front church residing in an area where strangers in the local community, whom often felt isolated because he or she could experience a feeling of belonging. -

Race, Migration, and Chinese and Irish Domestic Servants in the United States, 1850-1920

An Intimate World: Race, Migration, and Chinese and Irish Domestic Servants in the United States, 1850-1920 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Andrew Theodore Urban IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advised by Donna Gabaccia and Erika Lee June 2009 © Andrew Urban, 2009 Acknowledgements While I rarely discussed the specifics of my dissertation with my fellow graduate students and friends at the University of Minnesota – I talked about basically everything else with them. No question or topic was too large or small for conversations that often carried on into the wee hours of the morning. Caley Horan, Eric Richtmyer, Tim Smit, and Aaron Windel will undoubtedly be lifelong friends, mahjong and euchre partners, fantasy football opponents, kindred spirits at the CC Club and Mortimer’s, and so on. I am especially grateful for the hospitality that Eric and Tim (and Tank the cat) offered during the fall of 2008, as I moved back and forth between Syracuse and Minneapolis. Aaron and I had the fortune of living in New York City at the same time in our graduate careers, and I have fond memories of our walks around Stuyvesant Park in the East Village and Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and our time spent with the folks of Tuesday night. Although we did not solve all of the world’s problems, we certainly tried. Living in Brooklyn, I also had the opportunity to participate in the short-lived yet productive “Brooklyn Scholars of Domestic Service” (AKA the BSDS crew) reading group with Vanessa May and Lara Vapnek. -

The White Slave Trade and the Yellow Peril: Anti-Chinese Rhetoric and Women's Moral Authority a Thesis Submitted to the Depart

The White Slave Trade and the Yellow Peril: Anti-Chinese Rhetoric and Women’s Moral Authority A thesis submitted to the Department of History, Miami University, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History by Hannah E. Zmuda May 2021 Oxford, Ohio Abstract Despite the mid-to-late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s cultural preoccupation with white women’s sexual vulnerability, another phenomenon managed to take hold of public consciousness: “yellow slavery.” Yellow slavery was the variation of white slavery (known today as sex trafficking) that described the practice when Asian women were the victims. This thesis attempts to determine several of the reasons why Chinese women were included as victims in an otherwise exclusively white victim pool. One of the central reasons was the actual existence of the practice, which this thesis attempts to verify through the critical examination of found contracts and testimony of Chinese women. However, beyond just the existence of the practice of yellow slavery, many individuals used the sexual exploitation of Chinese women for their own cultural, religious, and political ends. Anti-Chinese agitators leveraged the image of the Chinese slave girl to frame anti-Chinese efforts as anti-slavery efforts, as well as to depict Chinese immigrants as incapable of assimilating into American culture and adhering to American ideals of freedom. Additionally, white missionaries created mission homes to shelter and protect the Chinese women and girls escaping white slavery. However, within these homes, the missionaries were then able to push their perceived cultural and religious superiority by pushing the home’s inmates into their ideals of Protestant, middle-class, white womanhood. -

Ginling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship

Ginling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship Rosalinda Xiong United World College of Southeast Asia Singapore, 528704 Abstract Ginling College (“Ginling”) was the first institution of higher learning in China to grant bachelor’s degrees to women. Located in Nanking (now Nanjing) and founded in 1915 by western missionaries, Ginling had already graduated nearly 1,000 women when it merged with the University of Nanking in 1951 to become National Ginling University. The University of Michigan (“Michigan”) has had a long history of exchange with Ginling. During Ginling’s first 36 years of operation, Michigan graduates and faculty taught Chinese women at Ginling, and Ginlingers furthered their studies at Michigan through the Barbour Scholarship. This paper highlights the connection between Ginling and Michigan by profiling some of the significant people and events that shaped this unique relationship. It begins by introducing six Michigan graduates and faculty who taught at Ginling. Next we look at the 21 Ginlingers who studied at Michigan through the Barbour Scholarship (including 8 Barbour Scholars from Ginling who were awarded doctorate degrees), and their status after returning to China. Finally, we consider the lives of prominent Chinese women scholars from Ginling who changed China, such as Dr. Wu Yi-fang, a member of Ginling’s first graduating class and, later, its second president; and Miss Wu Ching-yi, who witnessed the brutality of the Rape of Nanking and later worked with Miss Minnie Vautrin to help refugees in Ginling Refugee Camp. Between 2015 and 2017, Ginling College celebrates the centennial anniversary of its founding; and the University of Michigan marks both its bicentennial and the hundredth anniversary of the Barbour Gift, the source of the Barbour Scholarship. -

Teikichi Sunamoto

, September 1920 Missionary Voice Photo: The TEIKICHI SUNAMOTO A Founder of Methodism in Japan The Rev. Teikichi Sunamoto, 1857–1938, was a Sunamoto started a school for girls in Japanese Methodist pastor and evangelist working Hiroshima, married and became associated for with members of the missionary Lambuth family three years with the itinerate preaching of J.W. and in establishing the Methodist Church in Japan in W.R. Lambuth [later bishop] and O.A. Dukes, aiding the late 19th century. Following his death, World in opening work in numerous areas of Japan. Then Outlook magazine, then a publication of the he engaged in mission in Hawaii and San Francisco, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, said Sunamoto returning to Japan to become pastor of the Kojiya “was really the founder of our work in Japan.” Machi Methodist Church in Nagasaki under the Sunamoto joined the Japanese navy at age 16 Methodist Episcopal Mission. After six years there and served on gunboats until 1880. In that year, he and having made that church self-supporting, sailed on a merchant vessel to San Francisco and he rejoined the Southern Methodist Mission in left the military to get an education in the United 1900. From that time until he retired in 1927, he States. He came under the influence of Methodist accomplished much as pastor in Iwakuni, Mitajiri, evangelist Otis Gibson of the Gospel Society and Kure, Shimonoseki and Oishi. In his 80th year, he was baptized on May 7, 1881. Sunamoto worked for was still radiating faith and a holy influence over all. the Gospel Society until mid-1886 when he returned to Japan with the goal of leading his mother to Source: World Outlook, August, 1938, adapted from a profile by Missionary S.E Hager. -

Cheng Jingyi: Prophet of His Time Peter Tze Ming Ng

Cheng Jingyi: Prophet of His Time Peter Tze Ming Ng heng Jingyi (C. Y. Cheng, 1881–1939) distinguished him- missionary movement was dominated by organized missionary Cself by presenting what has been called the best speech at societies, most of them agencies of Western mainline denomi- the Edinburgh 1910 World Missionary Conference. In his remarks national churches. (The China Inland Mission was the primary he said: “As a representative of the Chinese Church, I speak entirely exception.) After 1900, however, there was a great increase in the from the Chinese standpoint. Speaking plainly we hope to amount of local, independent missionary work done by Chinese see, in the near future, a united Christian Church without any Christians. Much attention has been paid to the development of denominational distinctions. This may seem somewhat peculiar denominational Christianity in China, but only in more recent to you, but, friends, do not forget to view years have scholars begun to look into the us from our standpoint, and if you fail to growth of Chinese indigenous Christian- do that, the Chinese will remain always as ity immediately after 1900.5 Daniel Bays, a mysterious people to you.”1 for example, reports that “the number Jingyi was a Chinese born in Beijing of Protestant Christian church members on September 22, 1881. His father was a grew rapidly, from 37,000 in 1889 to 178,000 pastor with the London Missionary Soci- in 1906.” He also notes, “In retrospect, the ety (LMS). Jingyi received education from most important feature of this period was LMS’s Anglo-Chinese College in Beijing the growth of the spirit of independence and theological training from LMS’s theo- in Chinese Protestant churches. -

The Power to Save

The Power to Save A history of the gospel in China Bob Davey EP Books Faverdale North, Darlington, DL3 0PH, England e-mail: [email protected] web: www.epbooks.org EP Books USA P. O. Box 614, Carlisle, PA 17013, USA e-mail: [email protected] web: www.epbooks.us © R. W. Davey 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior permission of the publishers. First published 2011 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 13: 978 0 85234 743 0 ISBN: 0 85234 743 X Printed and bound in the UK by Charlesworth, Wakefield, West Yorkshire Contents Page List of illustrations 8 Foreword by Sinclair Ferguson 11 Preface 17 1. Chinas roots 21 2. Christianity in China up to AD 1800 28 3. Robert Morrison, the pioneer of the gospel to China, 1807 37 4. Charles Gutzlaff, pioneer explorer and missionary to China 53 5. Liang Afa: the first Chinese Protestant evangelist and pastor 69 6. Hudson Taylor: the making of a pioneer missionary, 183253 78 7. Hudson Taylor: up to the formation of the CIM, 185465 91 8. Hudson Taylor: establishing the China Inland Mission, 186575 107 9. Hudson Taylor: the triumph of faith, 18751905 120 10. The beginnings of a new century, 19001910 136 11. Birth of the republic and World War, 191020 151 12. Emergence of Chinese Christian leaders, 192030 163 13. Revivals, 193037 179 14. Awakening among university students, 193745 195 15. -

Asian American Naming Preferences and Patterns

"They Call Me Bruce, But They Won't Call Me Bruce Jones:" Asian American Naming Preferences and Patterns Ellen Dionne Wu Los Angeles, California The names of Asian Americans are indicative of their individual and collective experiences in the United States. Asian immigrants and their descendants have created, modified, and maintained their names by individual choice and by responding to pressures from the dominant . Anglo-American society. American society's emphasis on conformity has been a major theme in the history of Asian American naming conventions (as it has been for other groups), but racial differences and historical circumstances have forced Asian Americans to develop more fluid and more complex naming strategies as alternatives to simply adopting Anglo names, a common practice among European immigrants, thus challenging the paradigms of European-American assimilation and naming practices. Donald Duk does not like his name. Donald Duk never liked his name. He hates his name. He is not a duck. He is nota cartoon character. He does not go home to sleep in Disneyland every night. ... "Only the Chinese are stupid enough to give a kid a stupid name like Donald Duk," Donald Duk says to himself ... Donald Duk's father's name is King. King Duk. Donald hates his father's name. He hates being introduced with his father. "This is King Duk, and his son Donald Duk." Mom's name is Daisy . "That's Daisy Duk, and her son Donald .... " His own name is driving him crazy! (Frank Chin, Donald Duk, 1-2). Names 47.1 (March 1999):21-50 ISSN:0027-7738 @ 1999 by The American Name Society 21 22 Names 47.1 (March 1999) Names-family names, personal' names and nicknames-affect a person's life daily, sometimes for better, and sometimes, as in the case of Frank Chin's fictional character, Donald Duk, for worse.