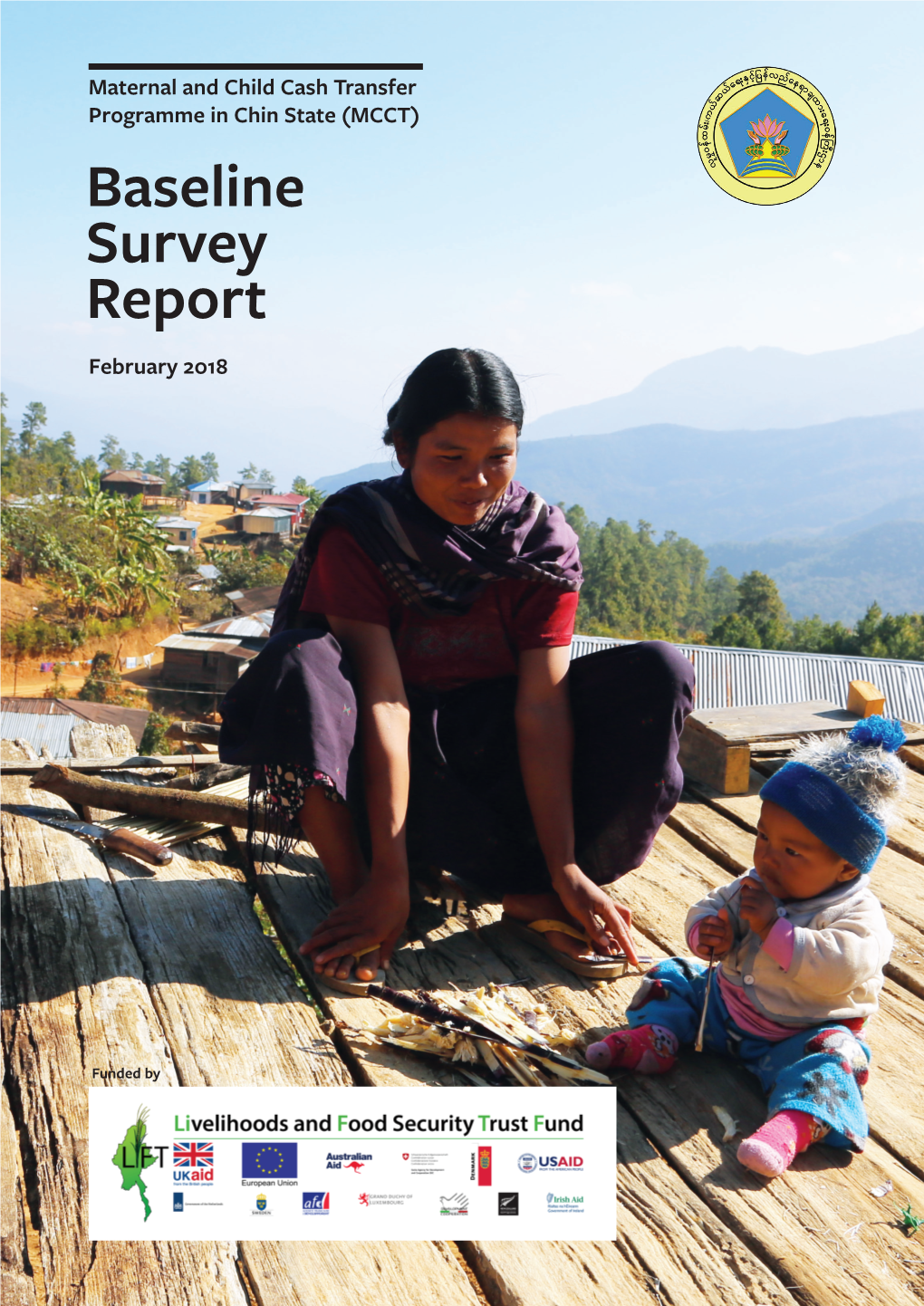

Baseline Survey Report February 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Facilities in Tonzang Township Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit School Facilities in Tonzang Township Chin State 93°20’E 93°30’E 93°40’E 93°50’E 94°0’E 94°10’E 94°20’E Bhutan India Kachin China Pangmual Bangladesh Sagaing Tualtel Shan Chin Vietnam Mandalay Magway Laos Kayah Rakhine Bago INDIA Yangon To ng ci in Kayin Ayeyarwady Thailand Tualkhiang Mon 24°0’N Cambodia 24°0’N Ta n in t h a ry i Aisih Suangbem Haicin Khenman Vanglai Thangsi Tuipialzang Phaisat Suangzang Khuaivum Sekpi Sihpek Tangsiat Suanghoih Linhnuat Cikha Lingthuk Selbung Cikha TAMU Sialmei Thuambual Khuadam Hiangzing Hawlkuam Tuimui Singpial Kansau A Senam Vaivet Mauvom Khuangkhan Bizang Kilometers 23°50’N 23°50’N Langphun Khiangkang 06123 Tuimang Tuilam Siallup Balbil Haipi Punpi Saipimual Khampat Legend Schools Sihtual TONZANG Taalzang Luangel Basic Education High School Singgial Madam Mualpi Basic Education High School (Branch) Mawngzang Basic Education Middle School Kampum Basic Education Middle School (Branch) Bapi Anlun Tuikhiang Khumnuai Basic Education Primary School Buangmual Basic Education Primary School (Branch) Suangpek Hangken Basic Education Primary School (Post) Zampi Khuabem Sopi Other Villages Mualkawi Khianglam Darkhai B Gelmual Main Town Township Boundary Darkhai B Tuitanzang Lihkhan Other Town District Boundary 23°40’N Khuamun 23°40’N Nakzang Stream State Boundary Seksih Ta lek Major Roads MAWLAIKInternational Boundary Aulun Phaidim Keltal Siabok Darkhai (A) Lungtak Minor Roads River/Water Body Tuitum Thauthe Khuavung Tonzang Khamzang Map ID: MIMU629v01 Tonzang Phaitu Creation -

School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State 93°20’E 93°40’E 94°0’E INDIA Hriangpi B Hlungmang THANTLANG Aika Hriangpi A Sate Lungcawi Sabaungte HAKHA Leikang Khuataw Langli Siatlai Darling Calthawng B Siatlai Laungva Lan Pi Calthawng A Lunthangtalang Ruava B Sharshi Ruava A Lotaw Calthawng A Sabaungpi Sapaw Zuamang Rezua Rezua Tinia Rezua Sawti Nabung Taungla Hinthang (Aminpi) Pintia Hinthang (Aminpi) Hinthang (Adauk) Hinthang (Thangpi) Marlar Ramsai Tuphei 22°0’N 22°0’N Lungdaw Darcung Ramsi Kilung Balei Lalengpi Lungpharlia Siangngo Tisi Sempi Thangdia Vawti Lungngo Etang Khoboei Aru Thaunglan Longring Tinam Lungkam Tibing (Old) Tilat Tibing (New) Sungseng B Cangceh Sungseng A MATUPI Hungle Zesaw Thesi Lailengte B Tingsi Lailengte A Raso Soitaung Ta ng ku TILIN Sakhai Khuangang Baneng Radui Taungbu Pasing Sakhai A Renkheng Pakheng Amlai Boithia Daidin Din Pamai Satu Tibaw Kace Raw Var Thiol Kihlung Anhtaw Boiring B Luivang Ngaleng Thicong Ngaleng Boiring A Thangping Congthia 21°40’N Lungtung 21°40’N Daihnam Phaneng Lalui Khuabal Tinglong Vuitu Leiring B Leiring A Nhawte B Bonghung Khuahung Okla Matupi Khwar Bway (West,East) BEHS(1,2)-Madupi Leisin Nhawte A Taung Lun Ramting Kala Kha Ma Ya(304) Thlangpang A Theboi Valangte Thlangpang B Haltu Hatu (Upper) Wun Kai Vapung Valangpi Amsoi B Cangtak Amsoi A Belkhawng Tuisip Lungpang Palaro Kuica MINDAT Lingtui Pangtui Khengca Thungna Thotui Sihleh Ngapang Madu Mindat Raukthang Rung 21°20’N 21°20’N Boisip Mitu Vuilu PALETWA Legend Main Town Schools Other -

Schools in Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Schools in Chin State 92°20'E 92°40'E 93°0'E 93°20'E 93°40'E 94°0'E TAMU Pangmual Tualtel Tongciin 24°0'N Tualkhiang 24°0'N Suangbem Legend Vanglai Haicin Phaisat Tuipialzang Khenman Khuaivum Suangzang Schools Sekpi Suanghoih Sihpek Lingthuk Cikha Selbung Khuadam KYIKHA Thuambual Basic Education High School Hiangzing Kansau A Tuimui Singpial Senam Khuangkhan Mauvom Basic Education High School (Branch) Vaivet Tuimang Siallup Tuilam Saipimual Balbil KHAMPAT Basic Education Middle School Luangel Madam Singgial Mualpi Mawngzang Tuikhiang Bapi Anlun Khumnuai Buangmual Basic Education Middle School (Branch) Suangpek Zampi Hangken Sopi Khuabem Khianglam Mualkawi Darkhai B Gelmual Darkhai B Lihkhan 23°40'N Tuitanzang 23°40'N Basic Education Primary School Nakzang Khuamun Seksih Talek Keltal Lungtak INDIA Tuitum Siabok Tonzang Thauthe Khuavung Khamzang Basic Education Primary School (Branch) Lalta Pangzang Tonzang Phaitu Poe Zar Chan TONZANG Tuipi Tuigel Tungtuang Cauleng Suangsang Salzang Buangzawl Basic Education Primary School (Post) Gamlai Takzang Tuikhingzang Ngente Lamthang Ngalbual Vialcian Lomzang Buanli Gelzang Sialthawzang Tungzang Pharthlang Anlangh Dampi Kamngai Tuithang Dimzang Bukphil Tualmu Taaklam Tuisanzang Phaiza Tuithang Lezang Mawngken Aipha Khiangzang Bumzang Thinglei Thenzang Thalmual (Old) Khuadai Zozang (Upper) Mawnglang Zimte Tualzang Kahgen Muallum Tongsial Thangzang Zimpi Kimlai Tuilangh Gawsing Lailui Haupi Vongmual Cingpikot Lailo Tuicinlui Mualnuam A Mualnuam B Teeklui Haupi (New) -

Hild Focused Local Social Plan, Chin State

Child Focused Local Social Plan, Chin State A policy document supporting Chin State’s Comprehensive 5-year Development Plan and Annual Planning 2016 – 2021 October 2014 Acknowledgements The Local Social Plan (LSP) is an initiative tha t UNICEF has been successfully developing and implementing in a number of countries. The work carried out in Chin State by the Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development (MIID), with UNICEF’s financial and technical assistance, is designed to develop a LS P for Chin State – as part of the State Comprehensive Development Plan - and establish a LSP methodology that may be replica ble in other states and regions of Myanmar. Danida has provided generous financial support. Myanmar Institute for Integrated D evelopment 41/7 B, Golden Hill Avenue Bahan Township Yangon Myanmar Contact: [email protected] Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS I MAP OF CHIN STATE II 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. THE CURRENT SITUATION IN CHIN STATE 1 2.1 DEMOGRAPHICS 2 2.2 GENDER ROLES 3 2.3 CHIN STATE – CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES 4 3. KEY FEATURES OF SOCIAL PROBLEMS IN CHIN STATE 5 3.1 CAPACITY FOR SOCIAL PROTECTION 5 3.1.1 INSTITUTIONAL SET -UP 5 3.1.2 CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS 6 3.2 SOCIAL PROTECTION AND VULNERABLE GROUPS 7 3.2.1 CHILDREN 7 3.2.2 WOMEN AND GENDER EQUALITY 10 3.2.3 PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 12 3.2.4 ELDERLY PEOPLE 14 3.3 EDUCATION SERVICES 16 3.3.1 SCHOOL ENROLMENT AND HUMAN RESOURCES 17 3.3.2 LIMITED ACCESS TO PRE -SCHOOLS 18 3.3.3 DROP -OUTS 18 3.3.4 NO EDUCATION OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES 19 3.3.5 POOR LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTS AND VERNACULAR TEACHING 19 3.3.6 QUALITY OF TEACHING AND THE EFFECTS OF ISOLATION 19 3.4 PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES AND HEALTH SITUATION 20 3.4.1 ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE SERVICES 20 3.4.2 LACK OF FOOD SECURITY 23 3.4.3 COMMUNICABLE DISEASES 24 3.4.4 REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS 26 4. -

Infrastructure and Urban Development Plans P in Chin State

Chin State Investment and Product Fair 16th March 2019 Myanmar Convention Center, Yangon Infrastructure and Urban Development Plans in Chin State Daw Aye Aye Myint Deputy Director General Department of Urban and Housing Development Ministry of Construction Contents • Business opportunities to invest in road infrastructure in Chin State • National Spppatial Development Framework Plan • Urban and Regional Planning • Hierarchy of Urban Development Planning • Urbanization, Population and Potential in Chin State • Town Development Concept Plans in Chin State • Urban System, Urban Transformation and the Role of Cities in Chin State Overview of Chin State Area 36000 Square kilometer (5. 3%) of the whole Myanmar Population 518,614 (1.02%) of the whole Myanmar Total length of Road in Chin State -10770.76 kilometer Total Length of Roads in Chin State Under DOH -2119.329 km (1316 miles 7.25 Furlong) Total Length of Union Roads in Chin State Under DOH -(8) Roads 687. 0 km (426 mile 7 Furlong) Total Length of Provisional Roads in Chin State Under DOH-(25) Roads (1432.35km) (ill)(890 mil 0.12 Furlong) Government Budgets (2018-2019) - Union Budget - 16296.589 million (MMK) - Chin State Budget - 71541.493 million (MMK) Total - 87838.082 million (()MMK) Road Density - 0.059 km/km² - 4.09 km per 1000 people Per Capita Financing - 169370/- MMK Per Capita Annual Income -737636 MMK(2017-2018) Connectivity Dominant - Transport Linkage Objective - Movement of Peopp()le and Goods/ Tourism and Business(Trade)etc., Mode - (6) modes . Railway . Road -

'Threats to Our Existence'

Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma September, 2012 © Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on 2 Montavista Avenue Nepean ON K2J 2L3 Canada www.chro.ca Photos © CHRO Front cover: Chin ChrisƟ ans praying over a cross they were ordered to destroy by the Chin State authoriƟ es, Mindat township, July 2010. Back cover: Chin ChrisƟ an revival group in Kanpetlet township, May 2010. Design & PrinƟ ng: Wanida Press, Thailand ISBN: 978-616-305-461-6 Threats to Our Existence: PersecuƟ on of ethnic Chin ChrisƟ ans in Burma i Contents CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... i Figures and appendices .................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... v DedicaƟ on ...................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ viii About the Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on................................................................... ix RaƟ onale and methodology ........................................................................................... ix Foreword ....................................................................................................................... -

LIFT Call for Proposals Chin Programme 2019

LIFT Call for Proposals Chin Programme 2019 – 2023: Transforming Chin State through agriculture development, improved nutrition and health, and the creation of decent work Ref no: CfP/LIFT/2019/2/Chin Release date: 19 June 2019 Deadline: 13 August 2019 by 13:00 (Myanmar local time) Title: Chin Programme 2019 – 2023: Transforming Chin State through agriculture development, improved nutrition and health, and the creation of decent work. Budget: USD 9 million Estimated Start: November 2019 Duration: Three years 1. Background The Livelihoods and Food Security (LIFT) Fund is a multi-donor fund established in 2009 to address food insecurity and income poverty in Myanmar. LIFT 2019-2023 is funded by seven donors – the United Kingdom, the European Union, Australia, Switzerland, the United States, Canada and Ireland. The United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) is the Fund Manager for LIFT, administrating the funds and providing monitoring and oversight services. The overall goal of the LIFT Fund is to achieve a sustained reduction in the number of people living in hunger and poverty in Myanmar. LIFT strengthens the resilience and livelihoods of poor and vulnerable populations through interventions to raise income, decrease vulnerability, improve nutrition and support pro-poor policy development. LIFT works with a broad range of implementing partners, including non-governmental organizations, United Nations agencies, the Government of Myanmar, the private sector, civil society, academic and research institutions. The Fund is active in the four main agro-ecological zones of Myanmar and to date has reached more than 11.6 million people or roughly 26 per cent of rural Myanmar’s population; and is active in two-thirds of the country’s townships. -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

Rhododendron News March April 2015

Volume XVII, Issue II Rhododendron News March-April 2015 Rhododendron News Bimonthly Publication since 1998 Volume XVII, Issue II March-April 2015 Chin IDPs (Internally Displaced Persons) taking shelter near the Kaladan river after being forced to flee conflicts between the Arakan Army and the Burma Army (Photos: Khumi Media Group) Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO) 2-Montavista Avenue, Nepean, K2J 2L3, Canada Ph: 1-613-843-9484 Email: [email protected] Web: www.chro.ca Volume XVII, Issue II Rhododendron News March-April 2015 2 Table of Contents Arbitrary Taxation & Extortion Page 3-5 • Police extort money for bamboo and firewood • Police extort money from local traders • Families demanded money to release child soldiers • Staffs salaries deducted by dept head Other Human Rights Violations Page 5-7 • Matupi Times threatened after writing about robbery by Natala students • State govt deny permission for Falam human rights training • Two policemen rape Chin girl in Tonzang Township • Man arrested for beating 4-yr-old Rezua girl to death • UN urge Burmas govt to end impunity Humanitarian & Development Situation Page 8-12 • Dozens of children hospitalized for diarrhoea • Hakha hit hard by water shortages • Villagers flee as Arakan, Burma armies clash in Chin State • Villagers worried as Arakan-Burma armies clash continues • Govt approve airport construction in Chin State • Villagers fleeing conflicts in need of humanitarian aid • Villagers worried as bad weather disrupts cultivation Event Page 12-15 • Chin State to host third ethnic media conference -

Chin State Census Report Volume 3 - D

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Chin State Report : Census Report Volume 3 – D Volume Report : Census Report Chin State Chin State Census Report Volume 3 - D Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 Census Report Volume 3–D (Chin) The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Chin State Report Census Report Volume 3-D For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 2: Map of Chin State by Districts and Townships ii Census Report Volume 3–D (Chin) Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officersat the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Hakha Township - Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Hakha Township - Chin State 93°28'E 93°36'E !( 93°44'E 93°52'E 94°0'E 94°8'E BHUTAN R U I P Falam N A INDIA M Ü CHINA N N ' ' 0 0 5 5 ° ° 2 2 2 2 Kale LAOS Hairawn(164502) (Tiphul) !( Keipaw(217916) (Haiphai) Tiphul(164501) !( Chuncung(164503) (Tiphul) Rinpi(164515) !( (Chuncung) (Rinpi) Rinte(164516) !( !( (Rinpi) !( Hata(164518) (Haiphai) !( THAILAND Hranhring(164504) Haiphai(164517) (Hranhring) (Haiphai) !( !( Hniarlawn(164498) (Hniarlawn) Thantlang !( Phai(164521) (Farrawn) !( !( Fiarti(164520) (Farrawn) Dauchim(164522) Nabual(164496) !( (Dauchim) (Khuabe) !( !( Lunghnam(164497) (Khuabe) Khuabe(164495) !( !( !( N N ' (Khuabe) !( Beute(217913) Farrawn(164519) ' 0 (Farrawn) 0 4 (Khuabe) 4 ° Aive(164523) ° 2 (Dauchim) 2 2 !( Vanha(164525) 2 (Vanhar) !( Hakha !( Mangnu(164508) Hmaikhah(164526) Ruan(164527) (Bualtak) Cinkhua(164524) (Vanhar) (Ruan) !( (Dauchim) !( !( !( Bualtak(164507) Nipi(217914) (Bualtak) (Bualtak) !( !( Ruadeu(164528) (Ruan) !( Lichia(164500) Loklung(164499) (Loklung) (Loklung) !( !( Hrawngvun(164510) (Malsawm) !( Zokhua(164505) Vantlang(164511) (Zokhua) (Malsawm) !( !( Malsawm(164509) Ruavan(164514) (Malsawm) (Tinam) !( !( N N Buanlung(164553) ' ' 0 0 Zathal(164548) (Buanlung) Pumlen(164506) 3 3 !( (Sakta) ° ° (Zokhua) 2 2 !( 2 2 !( Tinam(164512) (Tinam) Lamtuk(164513) !( (Tinam) !( Sakta(164547) (Sakta) !( Hakha Dongva(164554) Lan Boe(164550) (Bungtuah) (Dongva) !( Lungcawi(217915) !( (Tinam) !( Bungtuah(164549) Dinlaupa(217919) (Bungtuah) (Khuapi) !( !( Cintlang(164552) (Khuapi) -

CHIN STATE, MYANMAR WHO/WHAT/WHERE Organizations' Projects in July - December, 2011

Myanmar Information Management Unit CHIN STATE, MYANMAR WHO/WHAT/WHERE Organizations' Projects in July - December, 2011 Cikha Ü !( TONZANG (10) (AYO, GRET, MCC, PSI, UNDP, UNICEF, UNICEF(TBC), WFP(KMSS), UNOCHA) Tonzang !( Tedim Rihkhawdar !( !( TEDIM (11) India (CARE, GRET, KMSS, MCC, PSI, UNDP, UNICEF,UNICEF(TBC), WV, WFP(KMSS), UNOCHA) FALAM (7) (GRET, MCC, PSI, UNFPA, UNDP, UNICEF, UNOCHA) SAGAING Falam !( Thantlang !( Hakha THANTLANG (10) .! (CAD, CARD, GRET, MCC, MERLIN, PSI, UNDP, UNICEF, WFP(CAD), UNOCHA) HAKHA (13) (CAD, CARD, GRET, MERLIN, PSI, UNFPA, UNDP, UNICEF, WFP(ADRA), WFP(CAD), WFP(KMSS), YMCA, UNOCHA) Rezua !( Bangladesh MATUPI (8) (CAD, NGDO, PSI, UNDP, UNICEF, WFP(ADRA), UNOCHA) Matupi !( MINDAT (8) PALETWA (6) (CARE, MCC, PSI, (MEET, PSI, UNDP, UNICEF, IRC, UNDP, WFP(ADRA), UNOCHA) UNICEF, UNOCHA) Mindat !( MAGWAY Paletwa !( Kanpetlet !( KANPETLET (8) MANDALAY (MCC, MEET, PSI, SOLIDARITIES, UNDP, UNICEF, WFP(SOLIDARITIES), UNOCHA) RAKHINE Kilometers 0 10 20 40 .! State Capital Data sources: Boundaries - WFP/MIMU Map ID: MIMU238v05 Legend Place names - Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU. !( Main Town Who/What/Where data collated by the MIMU. Creation Date: 02 August 2011. A3 Number of Organizations !( Other Town 6 - 8 Note: This map represents information as it has been reported to MIMU by the Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 Township Boundary organisations concerned. Inclusion of an organisation on this map does not imply 9 - 11 District Boundary endorsement by the (HTC) Humanitarian Country Team or its projects. Note that this map only shows presence of organisations in a broad sector; it does not portray detailed 12 - 13 State Boundary information such as the volume of assistance, the number of benefeciaries, or the extent to Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] which needs are met or unmet.