The Chin State Floods & Landslides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar: Conflicts and Human Rights Violations Continue to Cause Displacement

5 March 2009 Myanmar: Conflicts and human rights violations continue to cause displacement Displacement as a result of conflict and human rights violations continued in Myanmar in 2008. An estimated 66,000 people from ethnic minority communities in eastern Myanmar were forced to become displaced in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict and human rights abuses. As of October 2008, there were at least 451,000 people reported to be inter- nally displaced in the rural areas of eastern Myanmar. This is however a conservative fig- ure, and there is no information available on figures for internally displaced people (IDPs) in several parts of the country. In 2008, the displacement crisis continued to be most acute in Kayin (Karen) State in the east of the country where an intense offensive by the Myanmar army against ethnic insur- gent groups had been ongoing since late 2005. As of October 2008, there were reportedly over 100,000 IDPs in the state. New displacement was also reported in 2008 in western Myanmar’s Chin State as a result of human rights violations and severe food insecurity. People also continued to be displaced in some parts of the country due to a combination of coercive measures such as forced la- bour and land confiscation that left them with no choice but to migrate, often in the context of state-sponsored development initiatives. IDPs living in the areas of Myanmar still affected by armed conflict between the army and insurgent groups remained the most vulnerable, with their priority needs tending to be re- lated to physical security, food, shelter, health and education. -

ASEAN-India Strategic Partnership

A Think-Tank RIS of Developing Countries Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), a New Delhi based autonomous think-tank under the Ministry of External Affairs, ASEAN-India Strategic Government of India, is an organisation that specialises in policy research on international economic issues and development cooperation. RIS is Partnership envisioned as a forum for fostering effective policy dialogue and capacity- building among developing countries on international economic issues. The focus of the work programme of RIS is to promote South-South ASEAN-India Strategic Partnership Perspectives from the Cooperation and assist developing countries in multilateral negotiations in ASEAN-India Network of Think-Tanks various forums. RIS is engaged in the Track II process of several regional initiatives. RIS is providing analytical support to the Government of India in the negotiations for concluding comprehensive economic cooperation agreements with partner countries. Through its intensive network of policy think-tanks, RIS seeks to strengthen policy coherence on international economic issues. For more information about RIS and its work programme, please visit its website: www.ris.org.in — Policy research to shape the international development agenda RIS Research and Information System for Developing Countries Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003, India. Ph.: +91-11-24682177-80, Fax: +91-11-24682173-74 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ris.org.in ASEAN-India ASEAN Secretariat -

Hakha Chin Land and Resource Tenure Resource and Land Chin Hakha in Change and Persistence

PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCETENURE PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of and Lives Land series Myanmar research Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series PERSISTENCE AND CHANGE IN HAKHA CHIN LAND AND RESOURCE TENURE A STUDY ON LAND DYNAMICS IN THE PERIPHERY OF HAKHA M. Boutry, C. Allaverdian, Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series DISCLAIMER Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land This document is supported with financial assistance from Australia, Denmark, dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. the European Union, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and Published by GRET, 2018 the Mitsubishi Corporation. The views expressed herein are not to be taken to reflect the official opinion of any of the LIFT donors. Suggestion for citation: Boutry, M., Allaverdian, C. Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone. (2018). Persistence and change in Hakha Chin land and resource tenure: a study on land dynamics in the periphery of Hakha. Of lives of land Myanmar research series. GRET: Yangon. Written by: Maxime Boutry and Celine Allaverdian With the contributions of: Tin Myo Win, Khin Pyae Sone and Sung Chin Par Reviewed by: Paul Dewit, Olivier Evrard, Philip Hirsch and Mark Vicol Layout by: studio Turenne Of Lives and Land Myanmar research series The Of Lives and Land series emanates from in-depth socio-anthropological research on land and livelihood dynamics. -

Elephant Foot Yam Production in Southern Chin State ______

Value Chain Assessment: Elephant Foot Yam Production In Southern Chin State ___________________________________________________________________________________ January 2017 Commissioned by MIID and authored by Jon Keesecker, Trevor Gibson, and Tluang Chin Sung. Acknowledgements The report authors would like to thank Duncan MacQueen, Marc Le Quentrec, and Derek Glass for sharing their research into elephant foot yam production in Myanmar. This document has been produced for the Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific (RECOFTC) on behalf of the Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development (MIID) with funding from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the consultants and do not necessarily reflect those of RECOFTC, MIID, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs or any other stakeholder. MIID - Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development 12, Kanbawza Street Yangon Myanmar Phone +95 1 545170 [email protected] Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development | 2 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND 1.2 MAIN FINDINGS 1.3 RECOMMENDATIONS 2. RESEARCH BACKGROUND 6 2.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES 2.2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3. HISTORY OF EFY INDUSTRY IN CHIN STATE 8 4. BACKGROUND: CULTIVATION, PROCESSING AND MARKETS 10 4.1 TAXONOMY AND CHARACTERISTICS 4.2 CULTIVATION 4.3 CHIP PROCESSING 4.4 POWDER PROCESSING 4.5 MARKETS 5. OVERVIEW OF EFY VALUE CHAIN 18 5.1 ACTORS IN THE VALUE CHAIN 5.2 ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 5.3 SUPPORT SERVICES 5.4 SALES CHANNELS AND AGGREGATE OUTPUT 5.5 VALUE ADDITION 6. ANALYSIS OF VALUE CHAIN 29 6.1 ANALYSIS OF ACTOR CHOICE AND RATIONALE 6.2 ASSESSMENT OF MARKET PROSPECTS 6.3 COMPETITION WITHIN MYANMAR 7. -

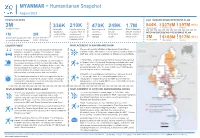

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit School Facilities in Matupi Township Chin State 93°20’E 93°40’E 94°0’E INDIA Hriangpi B Hlungmang THANTLANG Aika Hriangpi A Sate Lungcawi Sabaungte HAKHA Leikang Khuataw Langli Siatlai Darling Calthawng B Siatlai Laungva Lan Pi Calthawng A Lunthangtalang Ruava B Sharshi Ruava A Lotaw Calthawng A Sabaungpi Sapaw Zuamang Rezua Rezua Tinia Rezua Sawti Nabung Taungla Hinthang (Aminpi) Pintia Hinthang (Aminpi) Hinthang (Adauk) Hinthang (Thangpi) Marlar Ramsai Tuphei 22°0’N 22°0’N Lungdaw Darcung Ramsi Kilung Balei Lalengpi Lungpharlia Siangngo Tisi Sempi Thangdia Vawti Lungngo Etang Khoboei Aru Thaunglan Longring Tinam Lungkam Tibing (Old) Tilat Tibing (New) Sungseng B Cangceh Sungseng A MATUPI Hungle Zesaw Thesi Lailengte B Tingsi Lailengte A Raso Soitaung Ta ng ku TILIN Sakhai Khuangang Baneng Radui Taungbu Pasing Sakhai A Renkheng Pakheng Amlai Boithia Daidin Din Pamai Satu Tibaw Kace Raw Var Thiol Kihlung Anhtaw Boiring B Luivang Ngaleng Thicong Ngaleng Boiring A Thangping Congthia 21°40’N Lungtung 21°40’N Daihnam Phaneng Lalui Khuabal Tinglong Vuitu Leiring B Leiring A Nhawte B Bonghung Khuahung Okla Matupi Khwar Bway (West,East) BEHS(1,2)-Madupi Leisin Nhawte A Taung Lun Ramting Kala Kha Ma Ya(304) Thlangpang A Theboi Valangte Thlangpang B Haltu Hatu (Upper) Wun Kai Vapung Valangpi Amsoi B Cangtak Amsoi A Belkhawng Tuisip Lungpang Palaro Kuica MINDAT Lingtui Pangtui Khengca Thungna Thotui Sihleh Ngapang Madu Mindat Raukthang Rung 21°20’N 21°20’N Boisip Mitu Vuilu PALETWA Legend Main Town Schools Other -

I. Highlights • the Director General of the Union Ministry of Border Affairs Made a Visit to Chin State from 17 to 19 June. Th

This update covers the period from 1 June to 31 July 2011 and is issued on 1 August 2011. I. Highlights continuing the activities in some townships; and the • The Director General of the Union Ministry of validity of partners’ Memorandum of Understanding. Border Affairs made a visit to Chin state from 17 to 19 June. The DG expressed his Based on its recent logistic assessment in Chin appreciation of NGOs and UN work in State, WFP will not establish a warehouse in addressing Chin population’s needs. A similar Hakha. Its warehouse in Pakokku (Magway Region) message was conveyed by the Chief Minister will continue to cover Chin State. during a meeting with partners on 16 June, where he highlighted the need to further III. Sectors strengthen partnership in order to better assist the vulnerable populations across the State. Agriculture and livelihood – UNDP has established 46 food banks in Falam, Hakha, • In June, three landslides occurred in Hakha and Htantlang, Tiddim, Tonzang Townships to address also in some parts of the roads connecting the seasonal food shortages anticipated during the Hakha, Madupi and Rezua due to heavy rains. lean months of June, July and August. Borrower No casualties were reported. The roads were households will pay back, either in cash or in kind, re-opened upon the completion of road after the harvest in September and October. clearance facilitated by the Government. Food – WFP’s planned food distribution in Chin • An earthquake of magnitude 4.8 Richter scale State for the months of January to June has been was reported on 10 July at 7:10 am. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Schools in Chin State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Schools in Chin State 92°20'E 92°40'E 93°0'E 93°20'E 93°40'E 94°0'E TAMU Pangmual Tualtel Tongciin 24°0'N Tualkhiang 24°0'N Suangbem Legend Vanglai Haicin Phaisat Tuipialzang Khenman Khuaivum Suangzang Schools Sekpi Suanghoih Sihpek Lingthuk Cikha Selbung Khuadam KYIKHA Thuambual Basic Education High School Hiangzing Kansau A Tuimui Singpial Senam Khuangkhan Mauvom Basic Education High School (Branch) Vaivet Tuimang Siallup Tuilam Saipimual Balbil KHAMPAT Basic Education Middle School Luangel Madam Singgial Mualpi Mawngzang Tuikhiang Bapi Anlun Khumnuai Buangmual Basic Education Middle School (Branch) Suangpek Zampi Hangken Sopi Khuabem Khianglam Mualkawi Darkhai B Gelmual Darkhai B Lihkhan 23°40'N Tuitanzang 23°40'N Basic Education Primary School Nakzang Khuamun Seksih Talek Keltal Lungtak INDIA Tuitum Siabok Tonzang Thauthe Khuavung Khamzang Basic Education Primary School (Branch) Lalta Pangzang Tonzang Phaitu Poe Zar Chan TONZANG Tuipi Tuigel Tungtuang Cauleng Suangsang Salzang Buangzawl Basic Education Primary School (Post) Gamlai Takzang Tuikhingzang Ngente Lamthang Ngalbual Vialcian Lomzang Buanli Gelzang Sialthawzang Tungzang Pharthlang Anlangh Dampi Kamngai Tuithang Dimzang Bukphil Tualmu Taaklam Tuisanzang Phaiza Tuithang Lezang Mawngken Aipha Khiangzang Bumzang Thinglei Thenzang Thalmual (Old) Khuadai Zozang (Upper) Mawnglang Zimte Tualzang Kahgen Muallum Tongsial Thangzang Zimpi Kimlai Tuilangh Gawsing Lailui Haupi Vongmual Cingpikot Lailo Tuicinlui Mualnuam A Mualnuam B Teeklui Haupi (New) -

Hild Focused Local Social Plan, Chin State

Child Focused Local Social Plan, Chin State A policy document supporting Chin State’s Comprehensive 5-year Development Plan and Annual Planning 2016 – 2021 October 2014 Acknowledgements The Local Social Plan (LSP) is an initiative tha t UNICEF has been successfully developing and implementing in a number of countries. The work carried out in Chin State by the Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development (MIID), with UNICEF’s financial and technical assistance, is designed to develop a LS P for Chin State – as part of the State Comprehensive Development Plan - and establish a LSP methodology that may be replica ble in other states and regions of Myanmar. Danida has provided generous financial support. Myanmar Institute for Integrated D evelopment 41/7 B, Golden Hill Avenue Bahan Township Yangon Myanmar Contact: [email protected] Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS I MAP OF CHIN STATE II 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. THE CURRENT SITUATION IN CHIN STATE 1 2.1 DEMOGRAPHICS 2 2.2 GENDER ROLES 3 2.3 CHIN STATE – CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES 4 3. KEY FEATURES OF SOCIAL PROBLEMS IN CHIN STATE 5 3.1 CAPACITY FOR SOCIAL PROTECTION 5 3.1.1 INSTITUTIONAL SET -UP 5 3.1.2 CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS 6 3.2 SOCIAL PROTECTION AND VULNERABLE GROUPS 7 3.2.1 CHILDREN 7 3.2.2 WOMEN AND GENDER EQUALITY 10 3.2.3 PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 12 3.2.4 ELDERLY PEOPLE 14 3.3 EDUCATION SERVICES 16 3.3.1 SCHOOL ENROLMENT AND HUMAN RESOURCES 17 3.3.2 LIMITED ACCESS TO PRE -SCHOOLS 18 3.3.3 DROP -OUTS 18 3.3.4 NO EDUCATION OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES 19 3.3.5 POOR LEARNING ACHIEVEMENTS AND VERNACULAR TEACHING 19 3.3.6 QUALITY OF TEACHING AND THE EFFECTS OF ISOLATION 19 3.4 PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICES AND HEALTH SITUATION 20 3.4.1 ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE SERVICES 20 3.4.2 LACK OF FOOD SECURITY 23 3.4.3 COMMUNICABLE DISEASES 24 3.4.4 REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND RIGHTS 26 4. -

Myanmar Situation Update (10 to 16 May 2021)

Myanmar Situation Update (10 to 16 May 2021) Summary: One hundred days after the coup, the junta has pushed the region’s fastest-growing economy into an economic and humanitarian disaster. The World Bank forecast shows that Myanmar's economy is expected to contract by 10% in 2021, a sharp difference from the previous prediction of 5.9% growth in October 2020. There is a possible banking crisis which leads to cash shortages, limited access to social welfare payments and international remittances. Last week, Myanmar Kyat hit one of its lowest compared to the USD. The World Food Program also estimates that up to 3.4 million more people, particularly those in urban areas, will face hunger during the next six months. Price rises, hurting the poor and causing shortages of some essentials, including the costs of fuel and medicine. The junta called to reopen colleges, universities and schools soon but many students and educators are boycotting. As a result, around 13,000 staff had been suspended by May 8. The junta also announced job vacancies for educational positions to replace striking staff. Across Myanmar, the ordinary citizens have taken up any weapons available from air guns to traditional firearms and homemade bombs and arms have spread in Chin state, Sagaing, Magwe and Mandalay regions. Mindat township in Chin State reported more intensified fights between the civil resistance groups and the Myanmar military while clashes were reported in Myingyan township, Mandalay region and Tamu township, Sagaing region. According to our information, at least 43 bomb blasts happened across Myanmar in the past week and many of them were in Yangon’s townships. -

Southern Chin State Rapid Assessment Report Sept

First Rapid Assessment in Southern Chin State (30 th August 2010 to 9 th September 2010) Final Report Table of contents 1 Assessment rationale, objectives and methodology .................................................3 1.1 Context: worrying trends in Southern Chin State..............................................3 1.2 Objectives of the rapid assessment .................................................................4 1.3 Assessment methodology and constraints .......................................................4 2 Background information on the two townships: difficult access, few INGOs .............4 2.1 Mindat Township..............................................................................................4 2.2 Kanpetlet Township .........................................................................................5 3 Overview of local farming systems ...........................................................................6 3.1 Main crops and cropping systems....................................................................6 3.1.1 Slash-and-burn system ................................................................................6 3.1.2 Home gardens .............................................................................................7 3.1.3 Winter crops.................................................................................................7 3.1.4 Permanent crops..........................................................................................7 3.2 Farming calendar.............................................................................................8