The Clash of the Counter-Bureaucracy and Development by Andrew Natsios July 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Massport and Masspike Richard A

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 17 | Issue 2 Article 4 3-21-2002 The aP radox of Public Authorities in Massachusetts: Massport and Masspike Richard A. Hogarty University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Public Policy Commons, and the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation Hogarty, Richard A. (2002) "The aP radox of Public Authorities in Massachusetts: asM sport and Masspike," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 17: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol17/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Paradox of Public Authorities in Massachusetts The Paradox of Massport and Public Authorities in Masspike Massachusetts Richard A. Hogarty This case study provides historical context and fresh perspectives for those seek- ing to understand the ways in which independent authorities operate in Massa- chusetts. More specifically, it examines the controversial performances of two separate authorities that deal with transportation problems. One involves a fail- ure to detect terrorists breaching security at Logan Airport; the other entails a bitter dispute that arose over the delay in raising tolls on the turnpike to pay for the Big Dig project. With both in mind, this study describes the countervailing pressures that converge on the executive branch of state government as it con- fronts the prospect of holding these two authorities accountable. -

Hudson News and Review

HUDSON INSTITUTE News & Review WWW.HUDSON.ORG FALL 2008 FOUR NEW SCHOLARS EXPAND HUDSON’S NATIONAL SECURITY AND FOREIGN POLICY WORK Hudson Institute is proud to announce the arrival of four Senior Fellows, each HUDSON with extensive experience in foreign policy and national security. “These distin- guished scholars highlight the speed and strength with which Hudson’s research SCHOLARS portfolio is growing,” Chairman Allan Tessler says. “National security studies RESPOND were a core part of Herman Kahn’s legacy, and we’re pleased to be extending our work in this vital field.” TO RUSSIAN ANDREW NATSIOS served as Administrator for U.S. Agency for Inter- AGGRESSION national Development from 2001 until 2006, where he oversaw the agency’s AGAINST reconstruction programs in Afghanis tan, Iraq, and Sudan. In 2006, President Bush appointed him Special Coor dinator for International Disaster Assistance GEORGIA and Special Humanitarian Coordinator for the Sudan. Natsios served previously at USAID, first as Director of the Office of Foreign When Russia rolled its tanks and artillery into Georgia on the eve of Disaster Assistance and then as Assistant Administrator for the Bureau for Food the 2008 Olympics—initiating the and Humanitarian Assistance. He also served as a member CONTINUED ON PAGE 23 biggest European conflict since Clockwise from upper left, Douglas Feith, Andrew Natsios, Christopher Ford, and Hassan Mneimneh World War II—Hudson scholars were quickly sought out to dis- cuss the situation. From the inter- nal political ramifications in Rus- sia, to the constantly-changing geostrategic im plic a tions of the crisis, Hudson scholars examined the crisis from every angle. -

Andrew S. Natsios

Andrew S. Natsios 1221 Dale Drive/ Silver Spring, MD 20910 H: 301-587-1410. C: 301-646-9905 [email protected], [email protected] May 4, 2012 EDUCATION HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Kennedy School of Government, Cambridge, MA Masters of Public Administration, 1979 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, Washington, DC B.A. of History, 1971 HOLLISTON HIGH SCHOOL, Holliston, MA Graduated 1967 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Georgetown University, Walsh School of Foreign Service (January 2006-present) Distinguished Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy and Advisor on International Development Full time faculty in the Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service Courses: Great Famines, War, and Humanitarian Assistance and Contemporary Issues in International Development Hudson Institute. Senior Fellow. 2008-present. Department of State/White House (October 2006-December 2007) President’s Special Envoy to Sudan Responsible for reviewing the state of relations between the US and the Government of Sudan to address the crisis in Darfur and in the implementation of the North/South Comprehensive Peace Agreement, recommending changes in US policy, working to construct an international coalition to address the crisis, and negotiating with the Sudanese government, rebel groups, and the Government of Southern Sudan to implement the policy changes. U.S. Agency for International Development (May 2001 – January 2006) Administrator . Served as chief executive officer of US government’s foreign aid agency in charge of nearly $14 billion (up from $7.9 billion in FY 2001) dollar budget and worldwide workforce of 8,100 employees operating in 80 countries. Programs included infrastructure, economic growth and policy reform, international health, agriculture, environmental protection, microenterprise, democracy and governance, and humanitarian relief. -

America's Global Leadership: Why Diplomacy And

AMERICA’S GLOBAL LEADERSHIP: WHY DIPLOMACY AND DEVELOPMENT MATTER HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION FEBRUARY 27, 2019 Serial No. 116–8 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 35–366PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey STEVE WATKINS, -

Andrew S. Natsios George H

Andrew S. Natsios George H. W. Bush School of Government and Public Service Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs Texas A&M University February 17, 2021 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Director, Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs and E. Richard Schendel Distinguished Professor of the Practice (September 2013 - present), George H.W. Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A and M University (August 2012 - Present) • Serve as full time faculty member teaching courses in famine theory, humanitarian assistance, and crisis management and international development theory and practice. • As Director, provide grants for faculty research, host a speaker’s series, fund conferences and book publications, manage US Army fellows program, publish policy series, and oversee student capstone programs. Also, created a new Global Pandemic Policy Program to research and propose policy initiatives on pandemics in the developing world, the US response to global pandemics, and the risks and response to bio-terrorism. Distinguished Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy and Advisor on International Development, Georgetown University, Walsh School of Foreign Service (January 2006 - May 2012) • Full time faculty member at the Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service • Courses: Great Famines, War, and Humanitarian Assistance (graduate) and Contemporary Issues in International Development (undergraduate) Visiting Fellow, Center for Global Development (CGD), (2010). Provided counsel on issues related to international development, U.S. foreign policy, humanitarian assistance and Sudan. Wrote paper: Clash of the Counter-bureaucracy and Development. (2010) Senior Fellow on Foreign Policy and International Development. The Hudson Institute, Washington, D.C (2008 – Present) . Provide counsel on issues related to U.S. foreign policy, human rights, Middle East and North Africa, Afghanistan and Pakistan, humanitarian intervention and assistance, international organizations including the United Nations and issues related to sub-Saharan Africa and Sudan. -

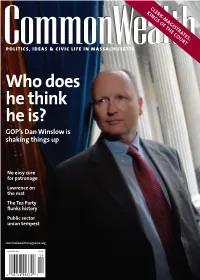

Who Does He Think He Is? GOP’S Dan Winslow Is Shaking Things Up

CLERK-MAGISTRATES: KINGS OF THE COURT POLITICS, IDEAS & CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS Who does he think he is? GOP’s Dan Winslow is shaking things up No easy cure for patronage Lawrence on the mat The Tea Party fl unks history Public sector union tempest commonwealthmagazine.org SPRING 2011 $5.00 99374 PS14592_BL11008_7-75x10-75.qxp:Commonwealth Magazine, 7.75x10.75 2/23/11 7:10 AM Page 1 Coverage from head to toe. Blue Cross Blue Shield for your health and dental. With connected coverage from Blue Cross Blue Shield, your health and dental work together. It’s better, more coordinated protection that also helps you stay well and save money. To learn more about our health and dental plans for your company, talk to your consultant, broker or call 1-800-262-BLUE. And get connected. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts is an Independent Licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. MP26256Recycle01-06_ 22-23 stats 3/22/11 5:53 PM Page 1 WHAT IS THE SIGN OF A GOOD DECISION?® It’s delivering the results that ma er. 2010 was a record year for MassMutual — good news for the policyholders who own our company. Despite challenging times, our solid operating fundamentals helped drive strong earnings, a record surplus of more than $10 billion, and an approved estimated dividend of $1.23 billion1 for our eligible participating policyholders. Beyond providing whole life insurance, retirement services and other nancial products, we strive to provide con dence — so our policyholders can enjoy today while being prepared for tomorrow. -

Umass Medicine } Umass Medical School Umass Memorial Health Care

Annual Report of Donors 2012 UMass Medicine } UMass Medical School UMass Memorial Health Care education care research Everyone can make a difference 012 UMass Medicine Annual Report of Donors Fiscal Year 2012 | July 1, 2011–June 30, 2012 education care research News Highlights . 2 John O’Brien announces retirement . 4 EDUCATION Alumni return and give back through scholarships . 5 Students support local communities . 8 CARE Grateful parents support care by giving back . 10 Enriching community health through a lifetime of philanthropy . 12 RESEARCH Biogen Idec gives major gift to UMass ALS Champion Fund . 14 Working toward targeted treatments for hereditary and other cancers . 16 An eventful year . 18 Our donors . 19 education care research From the Leadership Every year, this report gives us an opportunity to thank and recognize the most important contributors to the success of UMass Medical School and UMass Memorial Health Care—you, our donors. And every year, we are struck by your generosity, your kindness and, particularly, your willingness to partner with us in the best way possible: by making a gift. Through the stories in this report, you will see that there is a rich Michael F. Collins, MD variety to our donors, from the energetic teenager who is a fi rst-time Chancellor, University of Massachusetts fundraiser to the steadfast donors who have exhibited a lifetime of Medical School giving and commitment to their community. You will also see that, Senior Vice President for the Health Sciences, whether your gift was the fi rst or one of many, the breadth and University of Massachusetts depth of support demonstrates that everyone can give and that every gift makes a difference. -

After Saddam: Prewar Planning and the Occupation of Iraq, MG-642-A, Nora Bensahel, Olga Oliker, Keith Crane, Richard R

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Arroyo Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. After Saddam Prewar Planning and the Occupation of Iraq Nora Bensahel, Olga Oliker, Keith Crane, Richard R. -

History of Legislation

ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2007 FIRST SESSION ADJOURNED DECEMBER 19, 2007 CONVENED JANUARY 15, 2008 SECOND SESSION ADJOURNED DECEMBER 19, 2008 JOURNAL AND HISTORY OF LEGISLATION UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES BARNEY FRANK, Chairman FINAL EDITION — December 19, 2008 SECOND SESSION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES (RATIO: 37–33) BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts, Chairman PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama MAXINE WATERS, California DEBORAH PRYCE, Ohio CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MICHAEL N. CASTLE, Delaware LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois PETER T. KING, New York NYDIA M. VELÁZQUEZ, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York RON PAUL, Texas BRAD SHERMAN, California STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DENNIS MOORE, Kansas WALTER B. JONES, JR. North Carolina MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois RUBÉN HINOJOSA, Texas CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri GARY G. MILLER, California CAROLYN MCCARTHY, New York SHELLEY MOORE CAPITO, West Virginia JOE BACA, California TOM FEENEY, Florida STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JEB HENSARLING, Texas BRAD MILLER, North Carolina SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey DAVID SCOTT, Georgia GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida AL GREEN, Texas J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri JIM GERLACH, Pennsylvania MELISSA L. BEAN, Illinois STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas LINCOLN DAVIS, Tennessee TOM PRICE, Georgia PAUL W. HODES, New Hampshire GEOFF DAVIS, Kentucky KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota PATRICK MCHENRY, North Carolina RON KLEIN, Florida JOHN CAMPBELL, California TIM MAHONEY, Florida ADAM H. -

Governing Greater Boston: the Politics and Policy of Place

Governing Greater Boston The Politics and Policy of Place Charles C. Euchner, Editor 2002 Edition The Press at the Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston Cambridge, Massachusetts Copyright © 2002 by Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 79 John F. Kennedy Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 ISBN 0-9718427-0-1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Where is Greater Boston? Framing Regional Issues . 1 Charles C. Euchner The Sprawling of Greater Boston . 3 Behind the dispersal • The region’s new diversity • Reviving urban centers Improving the Environment . 10 Comprehensive approaches • Targeting specific ills • Community-building and the environment • Maintenance for a better environment Getting Around the Region . 15 New corridors, new challenges • Unequal transportation options • The limits of transit • The key to transit: nodes and density Housing All Bostonians . 20 Not enough money, too many regulations • Community resistance to housing Planning a Fragmented Region . 23 The complexity of cities and regions • The appeal of comprehensive planning • ‘Emergence regionalism’ . 28 Chapter 2 Thinking Like a Region: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives . 31 James C. O’Connell Boston’s Development as a Region . 33 Controversies over regionalism in history • The debate over metropolitan government The Parts of the Whole . 43 The subregions of Greater Boston • Greater Boston’s localism Greater Boston’s Regional Challenges . 49 The Players in Greater Boston . 52 Policy Options for Regionalism . 56 State politics and regionalism • Regional planning agencies • Using local government for regional purposes Developing a Regional Mindset . 60 A Strategic Regionalism for Greater Boston . 62 iii iv Governing Greater Boston Chapter 3 The Region as a Natural Environment: Integrating Environmental and Urban Spaces . -

Andrew S. Natsios George H

Andrew S. Natsios George H. W. Bush School of Government and Public Service Texas A&M University April 13, 2018 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Director, Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs and E. Richard Schendel Distinguished Professor of the Practice, George H.W. Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A and M University (August 2012 - Present) Serve as full time faculty member teaching courses in famine theory, humanitarian assistance, and crisis management and international development theory and practice. As Director, provide grants for faculty research, host a speakers series, fund conferences and book publications, manage US Army fellows program, publish policy series, and oversee student capstone programs. Also, created a new Global Pandemic Policy Program to research and propose policy initiatives on pandemics in the developing world, the US response to global pandemics, and the risks and response to bio-terrorism. Distinguished Professor in the Practice of Diplomacy and Advisor on International Development, Georgetown University, Walsh School of Foreign Service (January 2006 - May 2012) Full time faculty member at the Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service Courses: Great Famines, War, and Humanitarian Assistance (graduate) and Contemporary Issues in International Development (undergraduate) Visiting Fellow, Center for Global Development (CGD), (2010). Provided counsel on issues related to international development, U.S. foreign policy, humanitarian assistance and Sudan. Wrote paper: Clash of the Counter-bureaucracy and Development. (2010) Senior Fellow on Foreign Policy and International Development. The Hudson Institute, Washington, D.C (2008 – Present) . Provide counsel on issues related to U.S. foreign policy, human rights, Middle East and North Africa, Afghanistan and Pakistan, humanitarian intervention and assistance, international organizations including the United Nations and issues related to sub-Saharan Africa and Sudan.