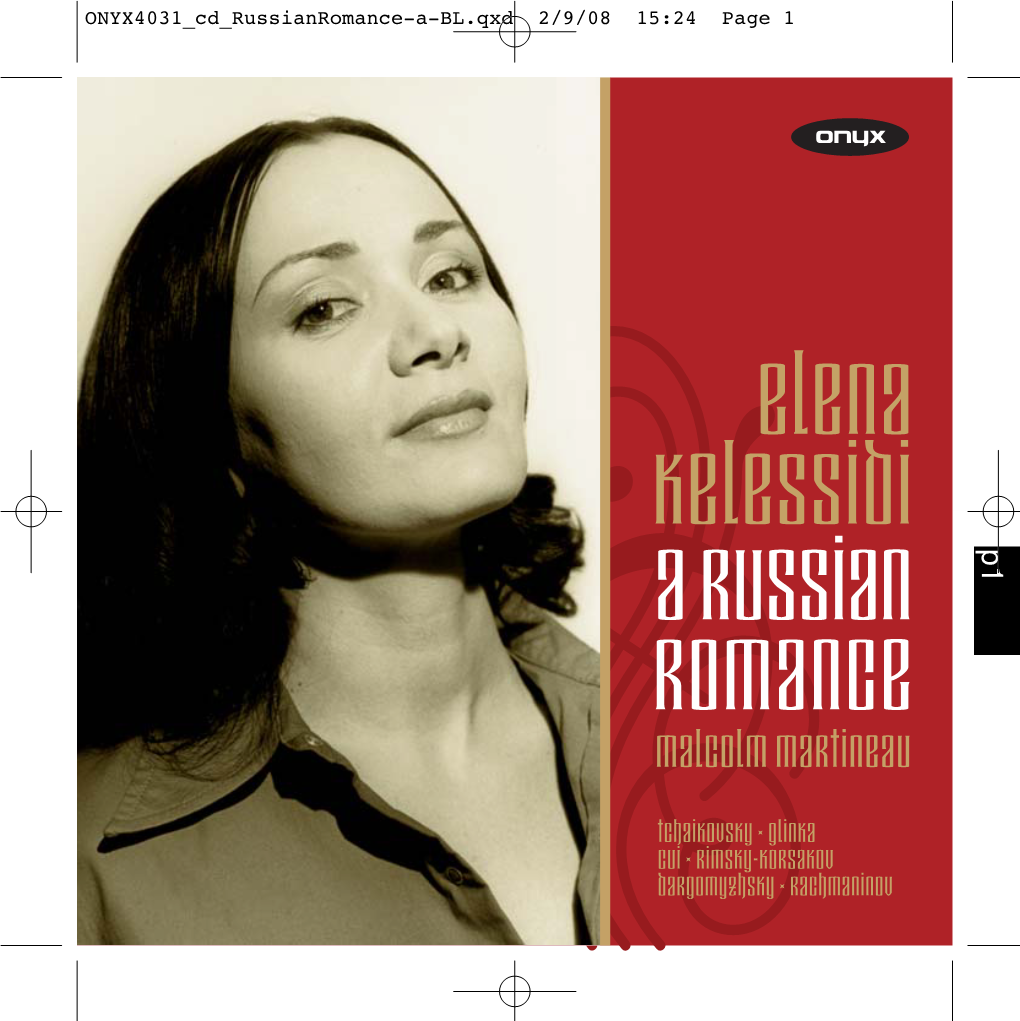

Elena Kelessidi a Russian Romance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Events May 2019

Public Events May 2019 Subscribe to this publication by emailing Shayla Butler at [email protected] Table of Contents Overview Highlighted Events ................................................................................................. 3 Youth Summer Camps ........................................................................................... 5 Neighborhood and Community Relations 1800 Sherman, Suite 7-100 Northwestern Events Evanston, IL 60208 Arts www.northwestern.edu/communityrelations Music Performances ..................................................................................... 15 Theater ......................................................................................................... 24 Art Exhibits .................................................................................................. 26 Dave Davis Art Discussions ............................................................................................. 27 Executive Director Film Screenings ............................................................................................ 27 [email protected] 847-491-8434 Living Leisure and Social ......................................................................................... 31 Norris Mini Courses Around Campus To receive this publication electronically ARTica (art studio) every month, please email Shayla Butler at Norris Outdoors [email protected] Northwestern Music Academy Religious Services ....................................................................................... -

Elena Kelessidi a Russian Romance

ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 1 elena kelessidi a russian p1 romance malcolm martineau tchaikovsky . glinka cui . rimsky-korsakov dargomyzhsky . rachmaninov r ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 2 p2 Malcolm Martineau ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) 1 Kolybel’naja pesnja Lullaby, op. 16 no. 1 3.46 2 Kaby znala ja Had I only known, op. 47 no. 1 4.31 3 Zabyt’ tak skoro So soon forgotten (1870) 3.02 4 Sret’ shumnava bala At the Ball, op. 38 no. 3 2.09 5 Ja li f pole da ne travushka byla The Bride’s Lament, op. 47 no. 7 6.01 MIKHAIL GLINKA (1804–1857) 6 V krovi gorit ogon’ zhelan’ja Fire in my Veins 1.15 7 K citre To a Lyre 3.28 8 Ne iskushaj menja bez nuzhdy Do not tempt me 2.41 9 Skazhi, zachem Tell me why 2.13 NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844–1908) 10 Plenivshis’ rozoj, solovej The Nightingale and the Rose, op. 2 no. 2 2.45 11 O chjom v tishi nochej In the quiet night, op. 40 no. 3 1.45 12 Ne veter veja s vysoty The Wind, op. 43 no. 2 1.42 CÉSAR CUI (1835–1918) 13 Kosnulas’ ja cvetka I touched a flower, op. 49 no. 1 1.39 ALEXANDER DARGOMYZHSKY (1813–1869) p3 14 Junoshu, gor’ko rydaja Young Boy and Girl 1.05 15 Ja vsjo jeshchjo jego ljublju I still love him 2.09 VLADIMIR VLASOV (1902–1986) 16 Bakhchisaraysky fontan The Fountain of Bakhchisarai 3.53 SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873–1943) 17 Ne poj, krasavica, pri mne Oh, do not sing to me, op. -

Xamsecly943541z Ç

Catalogo 2018 Confezione: special 2 LP BRIL 90008 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 95388 Medio Prezzo Medio Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 07/03/2017 Distribuzione Italiana 01/12/2017 Genere: Classica da camera Genere: Classica da camera Ç|xAMSECLy900087z Ç|xAMSECLy953885z JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHN ADAMS Variazioni Goldberg BWV 988 Piano Music - Opere per pianoforte China Gates, Phrygian Gates, American Berserk, Hallelujah Junction PIETER-JAN BELDER cv JEROEN VAN VEEN pf "Il minimalismo, ma non come lo conoscete”, così il Guardian ha descritto la musica di John Adams. Attivo in quasi tutti i generi musicali, dall’opera alle colonne sonore, dal jazz Confezione: long box 2 LP BRIL 90007 Medio Prezzo alla musica da camera, la sua apertura e il suo stile originale ha catturato il pubblico in Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 tutto il mondo, superando i confini della musica classica rigorosa. Anche nelle sue opere Genere: Classica da camera per pianoforte, il compositore statunitense utilizza un 'ampia varietà di tecniche e stili, come disponibile anche ci mostra il pioniere della musica minimalista Jeroen van Veen assecondato dalla moglie 2 CD BRIL 95129 Ç|xAMSECLy900070z Sandra van Veen al secondo pianoforte. Durata: 57:48 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 94047 YANN TIERSEN Medio Prezzo Pour Amélie, Goodbye Lenin (musica per Distribuzione Italiana 01/01/2005 pianoforte) Genere: Classica Strum.Solistica Ç|xAMSECLy940472z Parte A: Pour Amélie, Parte B: Goodbye Lenin JEROEN VAN VEEN pf ISAAC ALBENIZ Opere per chitarra Confezione: long box 1 LP BRIL 90006 Alto Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 Genere: Classica Orchestrale GIUSEPPE FEOLA ch disponibile anche 1 CD BRIL 94637 Ç|xAMSECLy900063z Isaac Albeniz, assieme a de Falla e Granados, è considerato non solo uno dei più grandi compositori spagnoli, ma uno dei padri fondatori della musica moderna spagnola. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2007/2 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: + 31 (0)20 679 65 75 CDs: + 31 (0)20 675 16 53 / fax: + 31 (0)20 664 67 59 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2007/2 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 10 PIANO 4-HANDS, PIANO 6-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS, CLAVICHORD, HARPSICHORD 11 ORGAN 14 PIANO AND ORGAN, KEYBOARD, ACCORDION 15 BANDONEON 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 15 VIOLIN SOLO, CELLO SOLO, DOUBLE BASS SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 15 VIOLIN with accompaniment 18 VIOLIN PLAY-ALONG, VIOLA with accompaniment. VIOLA PLAY-ALONG 19 CELLO with accompaniment 20 DOUBLE-BASS with accompaniment, VIOLA DA GAMBA / VIOL with accompaniment 20 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 27 FLUTE SOLO 28 OBOE SOLO, CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO 29 BASSOON SOLO, TRUMPET SOLO 30 HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO 31 TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 31 PICCOLO with accompaniment, FLUTE with accompaniment 32 FLUTE PLAY-ALONG, ALTO FLUTE with accompaniment 33 OBOE with accompaniment, CLARINET with accompaniment 34 CLARINET PLAY-ALONG, SAXOPHONE with accompaniment 35 SAXOPHONE PLAY-ALONG, BASSOON with accompaniment 36 HORN with accompaniment TRUMPET with accompaniment, TRUMPET PLAY-ALONG 37 TROMBONE with accompaniment, TUBA with accompaniment 2 -

Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) 1

WiTh LoVe FrOm RuSsIa Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) 1. Doubt* 4.41 15. The Pretty Girl No Longer Loves Me* 3.06 2. Where is our rose? 1.15 16. The Lovely Fisherwoman* 1.18 3. Cradle Song 4.13 17. Listen to my song, little friend* 3.21 4. Do not tempt me needlessly 2.57 Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953) From ‘Chout’ op.21 arr. for cello & piano by Roman Sapozhnikov From ‘Chout’ op.21 arr. for cello & piano by Roman Sapozhnikov 18. Chouticha 1.02 5. Chout & Chouticha 2.01 19. The sad merchant 1.55 6. The merchant’s dream 1.28 20. Dance of Chout’s daughters 1.11 Alexander Dargomyzhsky (1813–1869) Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) 7. I am sad 2.03 21. Mild stars shone down on us op.60/12 3.21 8. Elegy* 2.23 22. Night op.73/2 4.00 9. The Youth and the Maiden 1.09 23. Only he who knows longing op.6/6 3.03 10. The night zephyr 3.17 * Original arrangements for voice, piano & cello by the composer Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943) 11. Gopak (from Mussorgsky’s Sorochintsky Fair) 2.00 All other songs are arranged by Hans Eijsackers and 12. Morceaux de fantaisie op.3 5.39 Jan Bastiaan Neven 13. Do not sing, my beauty, in front of me op.4/4 4.27 Total timing: 62.51 (arr. for violin & tenor by Fritz Kreisler) 14. Prelude in G sharp minor op.32/12 2.50 Henk Neven baritone | Hans Eijsackers piano | Jan Bastiaan Neven cello Artist biographies can be found at www.onyxclassics.com Glinka’s hundred or so songs include several settings of his regular opera librettist The Caucasus has always been a subject of fear and fascination to Russia and Nestor Kukolnik. -

RUS421 Pushkin Professor Hilde Hoogenboom Spring 2011 LL420B, 480.965.4576 PEBE117, TR 12:00-1:15 [email protected] #18444 Office Hours: TR2-4 & by Appt

RUS421 Pushkin Professor Hilde Hoogenboom Spring 2011 LL420B, 480.965.4576 PEBE117, TR 12:00-1:15 [email protected] #18444 Office Hours: TR2-4 & by appt. Pushkin: The Invention of Russian Literature Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) was an acknowledged genius , the No. 1 writer during his lifetime, not because he wrote best-sellers (although he did), but because his work, and his personality and life, exemplified qualities that brought him recognition and fame . Pushkin traced his lineage to noble families and was the great grandson of Peter the Great’s Abyssinian general, Abram Petrovich Gannibal, born an African prince . Pushkin was the Russian Byron , the Russian Mozart of poetry. After graduating from the elite Lycée, at age 21, the publication of his first major poem, Ruslan and Ludmila (1820), created a sensation , especially when he was exiled to the south at the same time for circulating poems about freedom . In 1826, back in St. Petersburg, where the Emperor Nicholas I was his personal censor, Pushkin became a professional man of letters and established a literary journal. His greatest work, the novel in verse Eugene Onegin (1833), was acclaimed as “an encyclopedia of Russian life ” and was made into a beloved opera by Petr Tchaikovsky in 1878. Students copied his bawdy poetry in their albums. His reputation with women made mothers fear for their daughters. His marriage to the beautiful Natalia Goncharova led to a duel over her honor, in which he was killed . Since then, his stature in Russian literature has only increased and he is Russia’s national poet , a literary saint with statues throughout Russia and streets named after him in every town. -

Artsandculture

ARTSANDCULTURE CALENDAR OF EVENTS FALL 2018 Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center SUBSCRIBE to a weekly events digest Museum Hours and learn more about events featured Tuesday–Saturday: 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. Sunday: 2:00 p.m.–5:00 p.m. in this brochure: Closed on Mondays and national holidays. BOWDOIN.EDU/ARTS/CALENDAR Bowdoin College Museum of Art Museum Hours All events are subject to change. Go to bowdoin.edu for Tuesday–Saturday: 10:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. information on cancellations or time changes. Thursday until 8:30 p.m. Go to bowdoin.edu/live for live streaming events. Sunday: Noon–5:00 p.m. through October 28 Sunday 1:00 p.m.–5:00 p.m. starting November 4 Follow @BowdoinArts on Twitter and Instagram. Closed on Mondays and national holidays. To access the Bowdoin College campus map go to: bowdoin.edu/about/campus/maps TICKET INFORMATION All events are open to the public and free of charge unless otherwise Bowdoin College is committed to making its campus accessible noted. Ticket information will be listed within the event description. to persons with disabilities. Individuals who have special needs should contact the Office of Events and Summer Programs at PUBLIC 207-725-3433. Tickets available in person at the David Saul Smith Union Information desk. See event listing for release date. No holds The Bowdoin College Arts and Culture Calendar is produced by or reserves. A limited number of tickets may be available at the the Office of Communications and Public Affairs. -

The Early Songs of Sergei Prokofiev and Their Relation to the Synthesis of the Arts in Russia, 1890-1922

72-4478 EVANS, Robert Kenneth, 1922- THE EARLY SONGS OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND THEIR RELATION TO THE SYNTHESIS OF THE ARTS IN RUSSIA, 1890-1922. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Music University Microfilms, A XEROX Com pany, Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Robert Kenneth Evans 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE EARLY SONGS OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AMD THEIR RELATION TO THE SYNTHESIS OF THE ARTS IN RUSSIA 1890-1922 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robert Kenneth Evans, B.ÎI. Approved by Advisor School of Music PLEASE NOTE; Some papes have small and indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS. ACKNOVniiEDGEMENTS Permissions are gratefully acknowledged to quote from the following works: Anna Akhmatova. Works. Vol. II. "Anna Axmatova Considered in a Context of Art Nouveau", by Aleksis Rannit, Copyright 1968 by Inter-Language Literary Associates. A History of Russian Literature From Its Beoinninqs to 1900. by D, S. Mrsky. Copyright 1958 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. The Influence of French Symbolism on Russian Poetry, by Georgette Donchin. Copyright 1958 by Mouton & C©, Publishers. Modern Russian Poetrv. edited by Vladimir Markov and Merrill SparJTs. Copyright 1966, 1967 by MacGibbon & Kee Ltd., reprinted by permission of The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Modern Russian Literature, by Marc Slonim. Oxford University Press. People and Life 1891-1917, by Ilya Ehrenburg. Copyright 1952 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Poets of Modern Russia, by Renato Poggioli. Copyright 1960 by the Harvard University Press. -

![Music, Drama and Folklore in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Opera Snegurochka [Snowmaiden]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7076/music-drama-and-folklore-in-nikolai-rimsky-korsakovs-opera-snegurochka-snowmaiden-6287076.webp)

Music, Drama and Folklore in Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Opera Snegurochka [Snowmaiden]

MUSIC, DRAMA AND FOLKLORE IN NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV'S OPERA SNEGUROCHKA [SNOWMAIDEN] DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gregory A. Halbe, B.A., M.A., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Margarita L. Mazo, Adviser Prof. Lois Rosow ___________________________ Professor George Kalbouss Advisor School of Music Graduate Program ABSTRACT Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s third of his fifteen operas, Snegurochka [Snowmaiden], is examined here from historical and analytical perspectives. Its historical importance begins with the composer’s oft-expressed preference for this work. It was by far his most popular opera during his lifetime, and has endured as a staple of the operatic repertory in Russia to this day. Rimsky-Korsakov’s famous declaration that he considered himself for the first time an artist “standing on my own feet” with this work, Snegurochka also represents a revealing case study in the dissolution of the Russian Five, or moguchaia kuchka, as a stylistically cohesive group of composers. The opera’s dramatic source was a musical play by the same name by Aleksandr Ostrovsky, with music by Piotr Tchaikovsky. Rimsky-Korsakov solicited and received Ostrovsky’s permission to adapt the script into an opera libretto. Primary sources, including the composer’s sketchbooks, the first editions of the score and the subsequent revisions, and correspondence with Ostrovsky and others, reveal how he transformed the dramatic themes of Ostrovsky’s play, in particular the portrayal of the title character. Finally, the musical themes and other stylistic features of this opera are closely analyzed and compared with those of Richard Wagner’s music dramas. -

Russian 2624 Russian Literature Through Music

Russ 2624-1020 Tony Lin Fall 2017 Slavic Languages & Literatures Monday 2:30-5:25pm [email protected] Cathedral of Learning G19B Office: CL 1229B University of Pittsburgh Office hours: T&W 1-2pm & by appt. Russian Literature in Musical Adaptation Course Description: This course explores how music and literature interact or influence each other. As knowledge of music theory is not a prerequisite for this course, we will first build critical vocabulary to speak about music before studying examples of “transposition” – the retelling of a narrative in a different genre. We will consider the relationship from both directions: literature set to music and representations of music in literature. We will read, for example, plays and stories that are based on composers (such as Pushkin’s Mozart and Salieri). Additionally, we will explore the thematic use of music in short stories and novellas, such as the role of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata in Tolstoy’s eponymous novella. We will consider the following overarching questions: what are the literary and artistic implications when a story gets retold in a different genre? Does the composer stay faithful to the text or change it significantly to better align with his artistic agenda? What is the effect of reading a literary text in comparison to seeing its musical counterpart? Course Requirements: Regular attendance and participation in discussion, short reports, and final paper. *Those who read Russian should read the texts in the original. Readings: Primary Aaron Copland: What to Listen for in Music -

Musical Means in Mussorgsky's Songs and Dances of Death

Musical Means in Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death: A Singer’s Study Guide D.M.A. Document Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason Fuh, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2017 Document Committee: Dr. Robin Rice, Advisor Prof. Edward Bak Dr. Alexander Burry Prof. Katherine Rohrer Copyrighted by Jason Fuh 2017 Abstract Modest Mussorgsky’s song cycle Songs and Dances of Death is a series of four miniature dramatic scenes. The text was supplied by Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov, who developed a keen relationship with the composer when they shared an apartment. A glance at Mussorgsky’s musical life and growth in the “Mighty Handful” circle helps us comprehend the evolution of his compositional style. At the peak of his musical maturity, the composer devoted himself to compositions in the realist, nationalist style. However, Songs and Dances of Death seems to have softened the edge of his style by incorporating lyricism, and possibly also impressionism and symbolism, into his works. Mussorgsky’s music in Songs and Dances of Death is tonal but it does not adhere to a traditional Western music theoretical analysis. Therefore, the musical analysis presented is based on defining the terms musical environment and musical energy as they emerge from the compositional components, an approach that provides yet another dimension of musical understanding in works like Mussorgsky’s. Russian diction is discussed in great detail along with a comprehensive summary of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) system for the Russian language. -

The Netmagazine

Dorothea Redepenning Russian content in a European form The dialogue of cultures in music A look at the musical history of Saint Petersburg and the intercultural dialogue between Russian and European music. Ideas of what is to be considered "Russian" music and how it relates to "European" music have changed considerably in the course of Russian musical history. These changes have followed the general rhythm of European cultures. In other words, Russian music as an eminent musical art can only be comprehended in its exchange with non−Russian music and its contacts with other musical cultures that have driven it towards self−determination. Without such dialogue, music, like any art, remains provincial because it is not taken notice of internationally. This was the case of Russian music before 1700 and largely of Soviet music1. What makes music Russian, or more generally, typical of any nation, can be defined, on the one hand, on the level of the material and subject matter used: references to, or quotations from, folk music, and themes from a nation's history make the music specific to that particular nation. On the other hand, what is typical can also be defined on the level of method: if a composer decides to use elements of folklore or national history, then his work may become recognizably Russian, Italian or German; however, he shares the decision to work in this manner with every composer who wishes to create a "national" piece of music: the procedure or technique is international, or European. International musical languages When Peter the Great moved to Moscow in 1703, he took the Pridvorny khor, the Court Chapel2, with him and made it sing at the city's founding ceremony.