Elena Kelessidi a Russian Romance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Events May 2019

Public Events May 2019 Subscribe to this publication by emailing Shayla Butler at [email protected] Table of Contents Overview Highlighted Events ................................................................................................. 3 Youth Summer Camps ........................................................................................... 5 Neighborhood and Community Relations 1800 Sherman, Suite 7-100 Northwestern Events Evanston, IL 60208 Arts www.northwestern.edu/communityrelations Music Performances ..................................................................................... 15 Theater ......................................................................................................... 24 Art Exhibits .................................................................................................. 26 Dave Davis Art Discussions ............................................................................................. 27 Executive Director Film Screenings ............................................................................................ 27 [email protected] 847-491-8434 Living Leisure and Social ......................................................................................... 31 Norris Mini Courses Around Campus To receive this publication electronically ARTica (art studio) every month, please email Shayla Butler at Norris Outdoors [email protected] Northwestern Music Academy Religious Services ....................................................................................... -

Download PDF Booklet

THE CALL INTRODUCING THE NEXT GENERATION OF CLASSICAL SINGERS Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick Malcolm Martineau piano our future, now Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick THE CALL Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick Malcolm Martineau THE CALL FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) 1 Fischerweise (Franz von Schlechta) f 2’53 2 Im Frühling (Ernst Schulze) a 4’32 ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) 3 Mein schöner Stern (Friedrich Rückert) d 2’39 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) 4 An eine Äolsharfe (Eduard Mörike) f 3’52 ROBERT SCHUMANN 5 Aufträge (Christian L’Egru) b 2’30 GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) 6 Le papillon et la fleur (Victor Marie Hugo) e 2’08 CLAUDE ACHILLE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) 7 La flûte de Pan (Pierre-Félix Louis) b 2’45 REYNALDO HAHN (1874-1947) 8 L’heure exquise (Paul Verlaine) c 2’27 CLAUDE ACHILLE DEBUSSY 9 C’est l’extase (Paul Verlaine) a 2’54 FRANCIS POULENC (1899-1963) Deux poèmes de Louis Aragon (Louis Aragon) d 10 i C 2’44 11 ii Fêtes galantes 0’57 GABRIEL FAURÉ 12 Notre amour (Armand Silvestre) e 1’58 MEIRION WILLIAMS (1901-1976) 13 Gwynfyd (Crwys) c 3’25 HERBERT HOWELLS (1892-1983) 14 King David (Walter de la Mare) b 4’51 RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) 15 The Call (George Herbert) f 2’12 16 Silent Noon (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) c 4’03 BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) 17 The Choirmaster’s Burial (Thomas Hardy) d 4’08 IVOR GURNEY (1890-1937) 18 Sleep (John Fletcher) e 2’55 BENJAMIN -

Eif.Co.Uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #Edintfest THANK YOU to OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU to OUR FUNDERS and PARTNERS

eif.co.uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #edintfest THANK YOU TO OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU TO OUR FUNDERS AND PARTNERS Principal Supporters Public Funders Dunard Fund American Friends of the Edinburgh Edinburgh International Festival is supported through Léan Scully EIF Fund International Festival the PLACE programme, a partnership between James and Morag Anderson Edinburgh International Festival the Scottish Government – through Creative Scotland – the City of Edinburgh Council and the Edinburgh Festivals Sir Ewan and Lady Brown Endowment Fund Opening Event Partner Learning & Engagement Partner Festival Partners Benefactors Trusts and Corporate Donations Geoff and Mary Ball Richard and Catherine Burns Cruden Foundation Limited Lori A. Martin and Badenoch & Co. Joscelyn Fox Christopher L. Eisgruber The Calateria Trust Gavin and Kate Gemmell Flure Grossart The Castansa Trust Donald and Louise MacDonald Professor Ludmilla Jordanova Cullen Property Anne McFarlane Niall and Carol Lothian The Peter Diamand Trust Strategic Partners The Negaunee Foundation Bridget and John Macaskill The Evelyn Drysdale Charitable Trust The Pirie Rankin Charitable Trust Vivienne and Robin Menzies Edwin Fox Foundation Michael Shipley and Philip Rudge David Millar Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust Keith and Andrea Skeoch Keith and Lee Miller Miss K M Harbinson's Charitable Trust The Stevenston Charitable Trust Jerry Ozaniec The Inches Carr Trust Claire and Mark Urquhart Sarah and Spiro Phanos Jean and Roger Miller's Charitable Trust Brenda Rennie Penpont Charitable Trust Festival -

20 Singers from 15 Countries Announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019 15-22 June 2019

20 singers from 15 countries announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019 15-22 June 2019 • 20 of the world’s best young singers to compete in the 36th year of the BBC's premier voice competition • Competitors come from 15 countries, including three from Russia, two each from South Korea, Ukraine and USA, and one each from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, England, Guatemala (for the first time), Mexico, Mongolia, Portugal, South Africa and Wales • Extensive broadcast coverage across BBC platforms includes more LIVE TV coverage than ever before • High-level jury includes performers José Cura, Robert Holl, Dame Felicity Lott, Malcolm Martineau, Frederica von Stade alongside leading professionals David Pountney, John Gilhooly and Wasfi Kani • Value of cash prizes increased to £20,000 for the Main Prize and £10,000 for Song Prize, thanks to support from Kiri Te Kanawa Foundation • Song Prize trophy to be renamed the Patron’s Cup in recognition of this support • Audience Prize this year to be dedicated to the memory of much-missed baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, winner of BBC Cardiff Singer of the World in 1989, who died in 2017 • New partnership with Wigmore Hall sees all Song Prize finalists offered debut concert recitals in London’s prestigious venue, while Main Prize to be awarded a Queen Elizabeth Hall recital at London’s Southbank Centre Twenty of the world’s most outstanding classical singers are today [4 March 2019] announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019. The biennial competition returns to Cardiff between 15-22 June 2019 and audiences in the UK and beyond can follow all the live drama of the competition on BBC TV, radio and online. -

November 2016

November 2016 Igor Levit INSIDE: Borodin Quartet Le Concert d’Astrée & Emmanuelle Haïm Imogen Cooper Iestyn Davies & Thomas Dunford Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Brigitte Fassbaender Masterclasses Kalichstein/Laredo/ Robinson Trio Dorothea Röschmann Sir András Schiff and many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–X Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – X AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

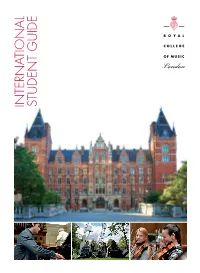

RCM International Student Guide.Pdf

INTERNATIONAL STUDENT GUIDE TOP WITH MORE THAN CONSERVATOIRE FOR 800 PERFORMING ARTS STUDENTS IN THE UK, SECOND IN FROM MORE THAN EUROPE AND JOINT THIRD IN THE WORLD QS WORLD UNIVERSITY RANKINGS 2016 60 COUNTRIES THE RCM IS AN INTERNATIONAL LOCATED OPPOSITE THE COMMUNITY ROYAL IN THE HEART OF LONDON ALBERT HALL HOME TO THE ANNUAL TOP UK SPECIALIST INSTITUTION BBC PROMS FESTIVAL FOR MUSIC COMPLETE UNIVERSITY GUIDE 2017 100% OF SURVEY RESPONDENTS IN OVER OF EMPLOYMENT OR 40% FURTHER STUDY STUDENTS BENEFIT FROM SIX MONTHS AFTER GRADUATION FOR SCHOLARSHIPS THREE CONSECUTIVE YEARS HIGHER EDUCATION STATISTICS AGENCY SURVEY CONCERTS AND MASTERCLASSES TOP LONDON WATCHED IN CONSERVATOIRE COUNTRIES FOR WORLD-LEADING WORLDWIDE IN 2014 75 RESEARCH VIA THE RCM’s RESEARCH EXCELLENCE FRAMEWORK YOUTUBE CHANNEL 2 ROYAL COLLEGE OF MUSIC / WWW.RCM.AC.UK WELCOME The Royal College of Music is one of the world’s greatest conservatoires, training gifted musicians from all over the globe for a range of international careers as performers, conductors and composers. We were proud to be ranked the top conservatoire for performing arts in the UK, second in Europe and joint third in the world in the 2016 QS World University Rankings. The RCM provides a huge Founded in 1882 by the future King Edward VII, number of performance the RCM has trained some of the most important opportunities for its students. figures in British and international music life. We hold more than 500 Situated opposite the Royal Albert Hall, our events a year in our building and location are the envy of the world. -

Xamsecly943541z Ç

Catalogo 2018 Confezione: special 2 LP BRIL 90008 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 95388 Medio Prezzo Medio Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 07/03/2017 Distribuzione Italiana 01/12/2017 Genere: Classica da camera Genere: Classica da camera Ç|xAMSECLy900087z Ç|xAMSECLy953885z JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHN ADAMS Variazioni Goldberg BWV 988 Piano Music - Opere per pianoforte China Gates, Phrygian Gates, American Berserk, Hallelujah Junction PIETER-JAN BELDER cv JEROEN VAN VEEN pf "Il minimalismo, ma non come lo conoscete”, così il Guardian ha descritto la musica di John Adams. Attivo in quasi tutti i generi musicali, dall’opera alle colonne sonore, dal jazz Confezione: long box 2 LP BRIL 90007 Medio Prezzo alla musica da camera, la sua apertura e il suo stile originale ha catturato il pubblico in Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 tutto il mondo, superando i confini della musica classica rigorosa. Anche nelle sue opere Genere: Classica da camera per pianoforte, il compositore statunitense utilizza un 'ampia varietà di tecniche e stili, come disponibile anche ci mostra il pioniere della musica minimalista Jeroen van Veen assecondato dalla moglie 2 CD BRIL 95129 Ç|xAMSECLy900070z Sandra van Veen al secondo pianoforte. Durata: 57:48 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 94047 YANN TIERSEN Medio Prezzo Pour Amélie, Goodbye Lenin (musica per Distribuzione Italiana 01/01/2005 pianoforte) Genere: Classica Strum.Solistica Ç|xAMSECLy940472z Parte A: Pour Amélie, Parte B: Goodbye Lenin JEROEN VAN VEEN pf ISAAC ALBENIZ Opere per chitarra Confezione: long box 1 LP BRIL 90006 Alto Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 Genere: Classica Orchestrale GIUSEPPE FEOLA ch disponibile anche 1 CD BRIL 94637 Ç|xAMSECLy900063z Isaac Albeniz, assieme a de Falla e Granados, è considerato non solo uno dei più grandi compositori spagnoli, ma uno dei padri fondatori della musica moderna spagnola. -

Fauré’S Craft Understandably 6

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 36 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 1. Ici-bas! Op. 8 No. 3 (ID)............................................................[1.36] 2. Au bord de l’eau, Op. 8 No. 1 (AM).................................. [2.48] 3. Chant d’automne, Op. 5 No. 1 (IB).................................... [3.37] 4. Vocalise 13 (LA)..............................................................................[1.10] 5. Tristesse d’Olympio (JC).........................................................[4.19] In sixty years of songwriting, between 1861 and 1921, Fauré’s craft understandably 6. Automne, Op. 18 No. 3 (IB).....................................................[2.36] developed in richness and subtlety. But many elements remained unchanged: among them, 7. Clair de lune, Op. 46 No. 2 (AM).........................................[3.15] a distaste for pretentious pianism (‘Oh pianists, pianists, pianists, when will you consent to 8. Spleen, Op. 51 No. 3 (AM)........................................................[2.11] hold back your implacable virtuosity !!!!’ he wrote, to a pianist, in 1919) and a loving care 9. Les roses d’Ispahan, Op. 39 No. 4 (JK)..............................[3.15] for prosody – not infrequently he ‘improved’ on the poet for musical reasons. Above all, he 10. La rose (Ode anacreontique), Op. 51 No. 4 (TO)........... [2.33] remained his own man. Henri Duparc was a close friend, but his songs, dubbed by Fauré’s 11. Le parfum impérissable, Op. 76 No. 1 (LA).................. [2.36] pupil Ravel ‘imperfect but works of genius’, had only a passing impact on Fauré’s own. -

A Prima Vista

A PRIMA VISTA a survey of reprints and of recent publications 2007/2 BROEKMANS & VAN POPPEL Van Baerlestraat 92-94 Postbus 75228 1070 AE AMSTERDAM sheet music: + 31 (0)20 679 65 75 CDs: + 31 (0)20 675 16 53 / fax: + 31 (0)20 664 67 59 also on INTERNET: www.broekmans.com e-mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS A PRIMA VISTA 2007/2 PAGE HEADING 03 PIANO 2-HANDS 10 PIANO 4-HANDS, PIANO 6-HANDS, 2 AND MORE PIANOS, CLAVICHORD, HARPSICHORD 11 ORGAN 14 PIANO AND ORGAN, KEYBOARD, ACCORDION 15 BANDONEON 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 15 VIOLIN SOLO, CELLO SOLO, DOUBLE BASS SOLO 1 STRING INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 15 VIOLIN with accompaniment 18 VIOLIN PLAY-ALONG, VIOLA with accompaniment. VIOLA PLAY-ALONG 19 CELLO with accompaniment 20 DOUBLE-BASS with accompaniment, VIOLA DA GAMBA / VIOL with accompaniment 20 2 AND MORE STRING INSTRUMENTS WITH AND WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITHOUT ACCOMPANIMENT: 27 FLUTE SOLO 28 OBOE SOLO, CLARINET SOLO, SAXOPHONE SOLO 29 BASSOON SOLO, TRUMPET SOLO 30 HORN SOLO, TROMBONE SOLO 31 TUBA SOLO 1 WIND INSTRUMENT WITH ACCOMPANIMENT, piano unless stated otherwise: 31 PICCOLO with accompaniment, FLUTE with accompaniment 32 FLUTE PLAY-ALONG, ALTO FLUTE with accompaniment 33 OBOE with accompaniment, CLARINET with accompaniment 34 CLARINET PLAY-ALONG, SAXOPHONE with accompaniment 35 SAXOPHONE PLAY-ALONG, BASSOON with accompaniment 36 HORN with accompaniment TRUMPET with accompaniment, TRUMPET PLAY-ALONG 37 TROMBONE with accompaniment, TUBA with accompaniment 2 -

Angelika Kirchschlager, Mezzo-Soprano Malcolm Martineau

Cal Performances Presents Program Sunday, April 19, 2009, 3pm Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957) Five Songs, Op. 38 (1948) Hertz Hall Glückwunsch Der Kranke Alt-Spanisch Angelika Kirchschlager, mezzo-soprano Alt-English My Mistress’ Eyes Malcolm Martineau, piano Kurt Weill (1900–1950) Stay Well, from Lost in the Stars (1949) Complainte de la Seine (1934) Der Abschiedsbrief (1933) PROGRAM Je ne t’aime pas (1934) Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Fischerweise, D. 881, Op. 96, No. 4 (1826) The concert is part of the Koret Recital Series and is made possible, in part, Der Wanderer an den Mond, D. 870 (1826) by Patron Sponsors Nancy and Gordon Douglass, in honor of Robert Cole. Bertas Lied in der Nacht, D. 653 (1819) Wehmut, D. 772, Op. 22, No. 2 (1823) Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo Bank. Frühlingsglaube, D. 686 (1820) Im Frühling, D. 882, Op. 101, No. 1 (1826) Schubert Die Sterne, D. 939, Op. 96, No. 1 (1815) Lied der Anne Lyle, D. 830, Op. 85, No. 1 (1825) Abschied, D. 475 (1816) Rastlose Liebe, D. 138 (1815) Klärchen’s Lied, D. 210 (1815) Geheimes, D. 719 (1821) Versunken, D. 715 (1821) INTERMISSION CANCELED CANCELED 6 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 7 Program Notes Program Notes Franz Schubert (1797–1828) suggests both the vigorous activity and the deep fashionable music lovers, and, in appreciation, his verses when Johann Schickh published some of Selected Songs contentment of the trade. he set five of Collin’s poems, including Wehmut them in his Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater Johann Gabriel Seidl (1804–1875), teacher, (“Sadness”) in 1823. -

Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) 1

WiTh LoVe FrOm RuSsIa Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) 1. Doubt* 4.41 15. The Pretty Girl No Longer Loves Me* 3.06 2. Where is our rose? 1.15 16. The Lovely Fisherwoman* 1.18 3. Cradle Song 4.13 17. Listen to my song, little friend* 3.21 4. Do not tempt me needlessly 2.57 Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953) From ‘Chout’ op.21 arr. for cello & piano by Roman Sapozhnikov From ‘Chout’ op.21 arr. for cello & piano by Roman Sapozhnikov 18. Chouticha 1.02 5. Chout & Chouticha 2.01 19. The sad merchant 1.55 6. The merchant’s dream 1.28 20. Dance of Chout’s daughters 1.11 Alexander Dargomyzhsky (1813–1869) Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) 7. I am sad 2.03 21. Mild stars shone down on us op.60/12 3.21 8. Elegy* 2.23 22. Night op.73/2 4.00 9. The Youth and the Maiden 1.09 23. Only he who knows longing op.6/6 3.03 10. The night zephyr 3.17 * Original arrangements for voice, piano & cello by the composer Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943) 11. Gopak (from Mussorgsky’s Sorochintsky Fair) 2.00 All other songs are arranged by Hans Eijsackers and 12. Morceaux de fantaisie op.3 5.39 Jan Bastiaan Neven 13. Do not sing, my beauty, in front of me op.4/4 4.27 Total timing: 62.51 (arr. for violin & tenor by Fritz Kreisler) 14. Prelude in G sharp minor op.32/12 2.50 Henk Neven baritone | Hans Eijsackers piano | Jan Bastiaan Neven cello Artist biographies can be found at www.onyxclassics.com Glinka’s hundred or so songs include several settings of his regular opera librettist The Caucasus has always been a subject of fear and fascination to Russia and Nestor Kukolnik. -

AGSA Newsletter April 2008

AGSA Newsletter April 2008 For the Members and Friends of the Accompanists’ Guild. Your Support is Needed - Now Deadline - Early Bird Conference applications close April 21 Publicity: The Malcolm Martineau visit is already “out there”. We have a team of 3 working on publicizing the Festival of Accompanists including the 4 Martineau Masterclasses, Young Accompanists on Show, The Geoffrey Parsons Award and the Conference of Accompanists and Associate Artists. The Conference includes a sparkling array of presentations, masterclasses and short recitals related to the Accompanist & Associate Artists (Singers & Instrumentalists) plus Malcolm’s Recital with Jonathan Lemalu. Media response has been encouraging with reference to the Festival, Conference & Recital already appearing in The Advertiser and on ABC Classic FM. Martineau interviews are already booked with 3 ABC presenters soon after he arrives. We must thank AGSA Committee member Chris Wainwright for his flood of media alerts for this (It is great to have time and expertise donated to the cause). Members & Friends - please become part of our publicity outreach - encourage your family, friends, associates to attend something - our priorities are the Conference and the Martineau/Lemalu Recital which you can attend as part of the Conference or as a single event ( single event book through Bass 131 246) Fundraising: This is the most difficult area to confront a group of accompanists (ie the AGSA Committee). Our efforts began mid 2007. Initially it was extremely hard to ask for donations – yes! Money!! It’s still foreign to us but at least we’ve grown thicker skins. We’ve had some exciting successes as well as many knock backs.