Russia and the Restricted Composer: Limitations of the Self, Culture, and Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Events May 2019

Public Events May 2019 Subscribe to this publication by emailing Shayla Butler at [email protected] Table of Contents Overview Highlighted Events ................................................................................................. 3 Youth Summer Camps ........................................................................................... 5 Neighborhood and Community Relations 1800 Sherman, Suite 7-100 Northwestern Events Evanston, IL 60208 Arts www.northwestern.edu/communityrelations Music Performances ..................................................................................... 15 Theater ......................................................................................................... 24 Art Exhibits .................................................................................................. 26 Dave Davis Art Discussions ............................................................................................. 27 Executive Director Film Screenings ............................................................................................ 27 [email protected] 847-491-8434 Living Leisure and Social ......................................................................................... 31 Norris Mini Courses Around Campus To receive this publication electronically ARTica (art studio) every month, please email Shayla Butler at Norris Outdoors [email protected] Northwestern Music Academy Religious Services ....................................................................................... -

8D09d17db6e0f577e57756d021

rus «Как дуб вырастает из желудя, так и вся русская симфоническая музыка повела свое начало из “Камаринской” Глинки», – писал П.И. Чайковский. Основоположник русской национальной композиторской школы Михаил Иванович Глинка с детства любил оркестр и предпочитал сим- фоническую музыку всякой другой (оркестром из крепостных музы- кантов владел дядя будущего композитора, живший неподалеку от его родового имения Новоспасское). Первые пробы пера в оркестро- вой музыке относятся к первой половине 1820-х гг.; уже в них юный композитор уходит от инструментального озвучивания популярных песен и танцев в духе «бальной музыки» того времени, но ориентируясь на образцы высокого классицизма, стремится освоить форму увертюры и симфонии с использованием народно-песенного материала. Эти опыты, многие из которых остались незаконченными, были для Глинки лишь учебными «эскизами», но они сыграли важную роль в формирова- нии его композиторского стиля. 7 rus rus Уже в увертюрах и балетных фрагментах опер «Жизнь за царя» (1836) Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский был младшим современником и «Руслан и Людмила» (1842) Глинка демонстрирует блестящее вла- и последователем Глинки в деле становления и развития русской про- дение оркестровым письмом. Особенно характерна в этом отноше- фессиональной музыкальной культуры. На репетициях «Жизни за царя» нии увертюра к «Руслану»: поистине моцартовская динамичность, он познакомился с автором оперы; сам Глинка, отметив выдающиеся «солнечный» жизнерадостный тонус (по словам автора, она «летит музыкальные способности юноши, передал ему свои тетради музыкаль- на всех парусах») сочетается в ней с интенсивнейшим мотивно- ных упражнений, над которыми работал вместе с немецким теоретиком тематическим развитием. Как и «Восточные танцы» из IV действия, Зигфридом Деном. Даргомыжский известен, прежде всего, как оперный она превратилась в яркий концертный номер. Но к подлинному сим- и вокальный композитор; между тем оркестровое творчество по-своему фоническому творчеству Глинка обратился лишь в последнее десяти- отражает его композиторскую индивидуальность. -

On Russian Music Might Win It

37509_u01.qxd 5/19/08 4:04 PM Page 27 1 Some Thoughts on the History and Historiography of Russian Music A preliminary version of this chapter was read as a paper in a symposium or- ganized by Malcolm H. Brown on “Fifty Years of American Research in Slavic Music,” given at the fiftieth national meeting of the American Musicological Society, on 27 October 1984. The other participants in the symposium and their topics were Barbara Krader (Slavic Ethnic Musics), Milos Velimirovic (Slavic Church Music), Malcolm H. Brown (Russian Music—What Has Been Done), Laurel Fay (The Special Case of Soviet Music—Problems of Method- ology), and Michael Beckerman (Czech Music Research). Margarita Mazo served as respondent. My assigned topic for this symposium was “What Is to Be Done,” but being no Chernïshevsky, still less a Lenin, I took it on with reluctance. I know only too well the fate of research prospectuses. All the ones I’ve seen, whatever the field, have within only a few years taken on an aspect that can be most charitably described as quaint, and the ones that have attempted to dictate or legislate the activity of future generations of scholars cannot be so charitably described. It is not as though we were trying to find a long- sought medical cure or a solution to the arms race. We are not crusaders, nor have we an overriding common goal that demands the subordina- tion of our individual predilections to a team effort. We are simply curious to know and understand the music that interests us as well as we possibly can, and eager to stimulate the same interest in others. -

4802170-Ccf435-053479213624.Pdf

1 Suite for Viola and Piano, Op. 8 - Varvara Gaigerova (1903-1944) 1. I. Allegro agitato 2:36 2. II. Andantino 3:06 3. III. Scherzo: Prest 4:25 4. IV. Moderato 4:47 Two Pieces for Viola and Piano, Op.31 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 5. I. Méditation élégiaque (Andante mesto poco mosso) 4:22 6. II. La toupie: scène d’enfant: Scherzino (Allegro vivace) 2:44 Sonata in D Major for Viola and Piano, Op. 15 - Paul Juon (1872-1940) 7. I. Moderato 7:09 8. II. Adagio assai e molto cantabile 6:13 9. III. Allegro moderato 6:50 Sonata in C minor for Viola and Piano, Op. 10 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 10. Moderato 9:59 11. Allegro agitato 6:28 12. L’istesso tempo ma poco rubato 4:24 Variations sur un air breton 13. Thème: Andante 1:06 14. Variation 1: L’istesso tempo poco rubato 1:39 15. Variation 2: Allegretto 1:06 16. Variation 3: Allegro patetico 1:10 17. Variation 4: Andante molto espressivo 1:23 18. Variation 5: Allegro con fuoco 1:18 19. Variation 6: Andante sostenuto 1:47 1 20. Variation 7: Fuga (Allegro moderato) 1:50 21. Coda: Poco più animato - Maestoso pesante 1:05 Total Time 71:02 In the early 20th century, composers Varvara Gaigerova, Alexander Winkler, and Paul Juon, reflect different aspects of Russian music at this historic time of intense social and political revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, in concert with the complex dynamics involved in the two great World Wars, created instability and hardship for most. -

ONYX4090 Cd-A-Bklt V8 . 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 Page 16:49 31/01/2012 V8

ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 p1 1 ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 2 Variations on a Russian folk song for string quartet (1898, by various composers) Variationen über ein russisches Volkslied Variations sur un thème populaire russe 1 Theme. Adagio 0.56 2 Var. 1. Allegretto (Nikolai Artsybuschev) 0.40 3 Var. 2. Allegretto (Alexander Scriabin) 0.52 4 Var. 3. Andantino (Alexander Glazunov) 1.25 5 Var. 4. Allegro (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) 0.50 6 Var. 5. Canon. Adagio (Anatoly Lyadov) 1.19 7 Var. 6. Allegretto (Jazeps Vitols) 1.00 8 Var. 7. Allegro (Felix Blumenfeld) 0.58 9 Var. 8. Andante cantabile (Victor Ewald) 2.02 10 Var. 9. Fugato: Allegro (Alexander Winkler) 0.47 11 Var. 10. Finale. Allegro (Nikolai Sokolov) 1.18 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 12 Russian Song 1.00 Russisches Lied · Mélodie russe p2 IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882–1971) 13 Concertino 6.59 ALFRED SCHNITTKE (1934–1998) 14 Canon in memoriam Igor Stravinsky 6.36 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 15 Old French Song 1.52 Altfranzösisches Lied · Mélodie antique française ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 3 16 Mama 1.32 17 The Hobby Horse 0.33 Der kleine Reiter · Le petit cavalier 18 March of the Wooden Soldiers 0.57 Marsch der Holzsoldaten · Marche des soldats de bois 19 The Sick Doll 1.51 Die kranke Puppe · La poupée malade 20 The Doll’s Funeral 1.47 Begräbnis der Puppe · Enterrement de la poupée 21 The Witch 0.31 Die Hexe · La sorcière 22 Sweet Dreams 1.58 Süße Träumerei · Douce rêverie 23 Kamarinskaya (folk song) 1.17 Volkslied · Chanson populaire p3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY String Quartet no.1 in D op.11 Streichquartett Nr. -

Elena Kelessidi a Russian Romance

ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 1 elena kelessidi a russian p1 romance malcolm martineau tchaikovsky . glinka cui . rimsky-korsakov dargomyzhsky . rachmaninov r ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 2 p2 Malcolm Martineau ONYX4031_cd_RussianRomance-a-BL.qxd 2/9/08 16:57 Page 3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) 1 Kolybel’naja pesnja Lullaby, op. 16 no. 1 3.46 2 Kaby znala ja Had I only known, op. 47 no. 1 4.31 3 Zabyt’ tak skoro So soon forgotten (1870) 3.02 4 Sret’ shumnava bala At the Ball, op. 38 no. 3 2.09 5 Ja li f pole da ne travushka byla The Bride’s Lament, op. 47 no. 7 6.01 MIKHAIL GLINKA (1804–1857) 6 V krovi gorit ogon’ zhelan’ja Fire in my Veins 1.15 7 K citre To a Lyre 3.28 8 Ne iskushaj menja bez nuzhdy Do not tempt me 2.41 9 Skazhi, zachem Tell me why 2.13 NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844–1908) 10 Plenivshis’ rozoj, solovej The Nightingale and the Rose, op. 2 no. 2 2.45 11 O chjom v tishi nochej In the quiet night, op. 40 no. 3 1.45 12 Ne veter veja s vysoty The Wind, op. 43 no. 2 1.42 CÉSAR CUI (1835–1918) 13 Kosnulas’ ja cvetka I touched a flower, op. 49 no. 1 1.39 ALEXANDER DARGOMYZHSKY (1813–1869) p3 14 Junoshu, gor’ko rydaja Young Boy and Girl 1.05 15 Ja vsjo jeshchjo jego ljublju I still love him 2.09 VLADIMIR VLASOV (1902–1986) 16 Bakhchisaraysky fontan The Fountain of Bakhchisarai 3.53 SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873–1943) 17 Ne poj, krasavica, pri mne Oh, do not sing to me, op. -

Lecture Slides

Lunch Lecture Inter-Actief will start at 12:50 ;lkj;lkj;lkj Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (orchestration: Maurice Ravel) Klaas Sikkel Münchner PhilharmonikerInter-Actief lunch conducted lecture, 15 Dec 2020 by Valery Gergiev 1 Pictures at an Exhibition and the Music of the Mighty Handful Inter-Actief Lunch Lecture 15 December 2020 Klaas Sikkel Muziekbank Enschede For Spotify playlist and more info see my UT home page (google “Klaas Sikkel”) Purpose of this lecture • Tell an entertaining story about a fragment of musical history • (hopefully) make you aware that classical music isn’t as boring as you thought, (possibly) raise some interest in this kind of music • Not a goal: make you a customer of the Muziekbank (instead, check out the Spotify playlist) Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 3 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) 4 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) • Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna (aunt of Tsar Alexander II, patroness) 5 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in 1859 Russia around 1860 Founding of the Two persons have contributed Russian greatly to professionalization and Musical Society practice of Classical -

The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera

Not Russian Enough The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera R H ©?=>> Rutger Helmers Print production by F&N Boekservice Typeset using: LATEX ?" Typeface: Linux Libertine Music typesetting: LilyPond Not Russian Enough: The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera Niet Russisch genoeg: nationalisme en de negentiende-eeuwse Russische operapraktijk (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) P ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magniVcus, prof. dr. G. J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag ? februari ?=>? des ochtends te >=.@= uur door Rutger Milo Helmers geboren op E november >FE= te Amersfoort Promotor: Prof. dr. E. G. J. Wennekes Co-promotor: Dr. M. V. Frolova-Walker Contents Preface · vii Acknowledgements · viii Preliminary Notes · x List of Abbreviations · xiii Introduction: The Part and the Whole · > Russia and the West · C The Russian Opera World · >= The Historiographical Legacy · >B Russianness RedeVned · ?> The Four Case Studies · ?A > A Life for the Tsar · ?F Glinka’s Changing Attitude to Italian Music · @@ The Italianisms of A Life for the Tsar · @F Liberties · BA Reminiscences · C> Conclusion · CB v vi CON TEN TS ? Judith · CD Serov the Cosmopolitan · D= Long-Buried Nationalities · E> Judith and Russianness · FE Conclusion · >=D @ The Maid of Orléans · >>> The Requirements of the Operatic Stage · >>C Schiller, The Maid, and Grand Opera Dramaturgy · >?> -

Xamsecly943541z Ç

Catalogo 2018 Confezione: special 2 LP BRIL 90008 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 95388 Medio Prezzo Medio Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 07/03/2017 Distribuzione Italiana 01/12/2017 Genere: Classica da camera Genere: Classica da camera Ç|xAMSECLy900087z Ç|xAMSECLy953885z JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHN ADAMS Variazioni Goldberg BWV 988 Piano Music - Opere per pianoforte China Gates, Phrygian Gates, American Berserk, Hallelujah Junction PIETER-JAN BELDER cv JEROEN VAN VEEN pf "Il minimalismo, ma non come lo conoscete”, così il Guardian ha descritto la musica di John Adams. Attivo in quasi tutti i generi musicali, dall’opera alle colonne sonore, dal jazz Confezione: long box 2 LP BRIL 90007 Medio Prezzo alla musica da camera, la sua apertura e il suo stile originale ha catturato il pubblico in Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 tutto il mondo, superando i confini della musica classica rigorosa. Anche nelle sue opere Genere: Classica da camera per pianoforte, il compositore statunitense utilizza un 'ampia varietà di tecniche e stili, come disponibile anche ci mostra il pioniere della musica minimalista Jeroen van Veen assecondato dalla moglie 2 CD BRIL 95129 Ç|xAMSECLy900070z Sandra van Veen al secondo pianoforte. Durata: 57:48 Confezione: Jewel Box 1 CD BRIL 94047 YANN TIERSEN Medio Prezzo Pour Amélie, Goodbye Lenin (musica per Distribuzione Italiana 01/01/2005 pianoforte) Genere: Classica Strum.Solistica Ç|xAMSECLy940472z Parte A: Pour Amélie, Parte B: Goodbye Lenin JEROEN VAN VEEN pf ISAAC ALBENIZ Opere per chitarra Confezione: long box 1 LP BRIL 90006 Alto Prezzo Distribuzione Italiana 15/12/2015 Genere: Classica Orchestrale GIUSEPPE FEOLA ch disponibile anche 1 CD BRIL 94637 Ç|xAMSECLy900063z Isaac Albeniz, assieme a de Falla e Granados, è considerato non solo uno dei più grandi compositori spagnoli, ma uno dei padri fondatori della musica moderna spagnola. -

Miki Aoki – Biography

Piano Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Contents: Mailing Address: Biography 1000 South Denver Avenue Reviews Suite 2104 Repertoire Tulsa, OK 74119 Sample Programs Website: YouTube Video Links http://www.pricerubin.com Photo Gallery Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Miki Aoki – Biography Miki Aoki made her London Royal Festival Hall debut at the age of 12 and has since continued to perform in international venues. Recognized for her diverse abilities as pianist and as collaborative artist, Ms. Aoki balances her career performing solo recitals and chamber music, with working alongside young violinists. Ms. Aoki is currently appointed Senior lecturer at Graz University for Music and the Performing Arts, in Austria. Recent and upcoming highlights include a Japan tour with violinist Andrey Baranov and appearances at St. Petersburg Philharmonic Hall, the Copenhagen Chamber Music Festival and the Menuhin Festival in Gstaad. Miki Aoki is recording exclusively for German label Hänssler Profil. Her first CD of Zoltan Kodaly's piano works was released in the fall of 2011 to critical acclaim. BBC Music magazine called it “...a genuinely memorable performance.” The second CD, ‘The Belyayev Project’, featuring fascinating compositions varying from solo piano works by Liadov, Glazunov and Blumenfeld to the piano Trio by Rimsky-Korsakov was released in spring 2013. Recorded this January, her Miki Aoki – Biography third CD ‘Melancolie’ (solo piano works by Francis Poulenc and other Les Six composers) is planned for release in 2016. -

GLAZUNOV Orchestral Works Including the 8 SYMPHONIES

GLAZUNOV Orchestral works including THE 8 SYMPHONIES Tadaaki Otaka BBC NATIONAL ORCHESTRA OF WALES / TADAAKI OTAKA BIS-CD-1663/64 BIS-CD-1663/64 Glaz:booklet 13/3/07 10:43 Page 2 GLAZUNOV, Alexander Konstantinovich (1865-1936) Disc 1 [72'53] Symphony No. 1 in E major, Op. 5 (1881-82) 34'48 1 I. Allegro 10'48 2 II. Scherzo. Allegro 5'02 3 III. Adagio 8'55 4 IV. Finale. Allegro 9'41 Symphony No. 6 in C minor, Op. 58 (1896) 37'27 5 I. Adagio – Allegro passionato 10'25 6 II. Tema con variazioni 11'25 7 III. Intermezzo. Allegretto 5'18 8 IV. Finale. Andante maestoso – Moderato maestoso 9'55 Disc 2 [64'20] Symphony No. 2 in F sharp minor, Op. 16 (1886) 43'10 1 I. Andante maestoso – Allegro 13'07 2 II. Andante 9'45 3 III. Allegro vivace 7'42 4 IV. INDEX 1 Intrada 1'23 – INDEX 2 Finale. Allegro 10'47 12'10 5 Mazurka in G major, Op. 18 (1888) 9'44 6 Ot mraka ka svetu, Op. 53 (1894) 10'14 (From Darkness to Light), Orchestral Fantasy 2 BIS-CD-1663/64 Glaz:booklet 13/3/07 10:43 Page 3 Disc 3 [60'23] 1 Ballade in F major, Op. 78 (1902) 9'35 Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 33 (1888-90) 50'15 2 I. Allegro 13'42 3 II. Scherzo. Vivace 9'26 4 III. Andante 13'07 5 IV. Finale. Allegro moderato 13'35 Disc 4 [75'11] Symphony No. -

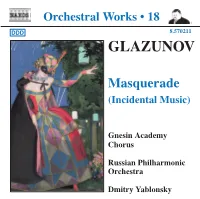

GLAZUNOV Masquerade

570211bk Glazunov US 8/5/09 16:23 Page 5 Gnesin Academy Chorus Dmitry Yablonsky The Gnesin Academy of Music is a State Institution in Moscow. Founded as a private music school by Elena, Dmitry Yablonsky was born in Moscow into a Orchestral Works • 18 Evgeniya and Mariya Gnesin in 1895, in 1920 it was divided into elementary school and secondary school, and later, musical family. His mother is the distinguished in 1944, became an Institute for Musical Education. The Academy adopted its present name in 1992, and includes pianist Oxana Yablonskaya, and his father Albert four schools, elementary school, ten-year primary school, secondary school and academy, with postgraduate Zaionz has for thirty years been principal oboist in DDD 8.570211 courses. The Gnesin Academy of Music includes a teaching staff of some four hundred, with over two thousand the Moscow Radio and Television Orchestra. Russian and foreign students. Dmitry began playing the cello when he was five and was immediately accepted by the Central Music School for gifted children. When he was nine he GLAZUNOV made his orchestral début as cellist and conductor Alexander Soloviev, Chorus-master with Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major. In Russia he studied with Stefan Kalianov, Rostropovich’s Alexander Soloviev was born in 1975 and studied at the Music School in Kostroma and at the Gnesin School. In assistant, and Isaak Buravsky, for many years solo 1995 he won first prize and special prize in the All-Russia Choral Conductors’ Competition and in 2001 took the cello of the Bolshoy Theatre Orchestra.