GLAZUNOV Orchestral Works Including the 8 SYMPHONIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8D09d17db6e0f577e57756d021

rus «Как дуб вырастает из желудя, так и вся русская симфоническая музыка повела свое начало из “Камаринской” Глинки», – писал П.И. Чайковский. Основоположник русской национальной композиторской школы Михаил Иванович Глинка с детства любил оркестр и предпочитал сим- фоническую музыку всякой другой (оркестром из крепостных музы- кантов владел дядя будущего композитора, живший неподалеку от его родового имения Новоспасское). Первые пробы пера в оркестро- вой музыке относятся к первой половине 1820-х гг.; уже в них юный композитор уходит от инструментального озвучивания популярных песен и танцев в духе «бальной музыки» того времени, но ориентируясь на образцы высокого классицизма, стремится освоить форму увертюры и симфонии с использованием народно-песенного материала. Эти опыты, многие из которых остались незаконченными, были для Глинки лишь учебными «эскизами», но они сыграли важную роль в формирова- нии его композиторского стиля. 7 rus rus Уже в увертюрах и балетных фрагментах опер «Жизнь за царя» (1836) Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский был младшим современником и «Руслан и Людмила» (1842) Глинка демонстрирует блестящее вла- и последователем Глинки в деле становления и развития русской про- дение оркестровым письмом. Особенно характерна в этом отноше- фессиональной музыкальной культуры. На репетициях «Жизни за царя» нии увертюра к «Руслану»: поистине моцартовская динамичность, он познакомился с автором оперы; сам Глинка, отметив выдающиеся «солнечный» жизнерадостный тонус (по словам автора, она «летит музыкальные способности юноши, передал ему свои тетради музыкаль- на всех парусах») сочетается в ней с интенсивнейшим мотивно- ных упражнений, над которыми работал вместе с немецким теоретиком тематическим развитием. Как и «Восточные танцы» из IV действия, Зигфридом Деном. Даргомыжский известен, прежде всего, как оперный она превратилась в яркий концертный номер. Но к подлинному сим- и вокальный композитор; между тем оркестровое творчество по-своему фоническому творчеству Глинка обратился лишь в последнее десяти- отражает его композиторскую индивидуальность. -

On Russian Music Might Win It

37509_u01.qxd 5/19/08 4:04 PM Page 27 1 Some Thoughts on the History and Historiography of Russian Music A preliminary version of this chapter was read as a paper in a symposium or- ganized by Malcolm H. Brown on “Fifty Years of American Research in Slavic Music,” given at the fiftieth national meeting of the American Musicological Society, on 27 October 1984. The other participants in the symposium and their topics were Barbara Krader (Slavic Ethnic Musics), Milos Velimirovic (Slavic Church Music), Malcolm H. Brown (Russian Music—What Has Been Done), Laurel Fay (The Special Case of Soviet Music—Problems of Method- ology), and Michael Beckerman (Czech Music Research). Margarita Mazo served as respondent. My assigned topic for this symposium was “What Is to Be Done,” but being no Chernïshevsky, still less a Lenin, I took it on with reluctance. I know only too well the fate of research prospectuses. All the ones I’ve seen, whatever the field, have within only a few years taken on an aspect that can be most charitably described as quaint, and the ones that have attempted to dictate or legislate the activity of future generations of scholars cannot be so charitably described. It is not as though we were trying to find a long- sought medical cure or a solution to the arms race. We are not crusaders, nor have we an overriding common goal that demands the subordina- tion of our individual predilections to a team effort. We are simply curious to know and understand the music that interests us as well as we possibly can, and eager to stimulate the same interest in others. -

4802170-Ccf435-053479213624.Pdf

1 Suite for Viola and Piano, Op. 8 - Varvara Gaigerova (1903-1944) 1. I. Allegro agitato 2:36 2. II. Andantino 3:06 3. III. Scherzo: Prest 4:25 4. IV. Moderato 4:47 Two Pieces for Viola and Piano, Op.31 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 5. I. Méditation élégiaque (Andante mesto poco mosso) 4:22 6. II. La toupie: scène d’enfant: Scherzino (Allegro vivace) 2:44 Sonata in D Major for Viola and Piano, Op. 15 - Paul Juon (1872-1940) 7. I. Moderato 7:09 8. II. Adagio assai e molto cantabile 6:13 9. III. Allegro moderato 6:50 Sonata in C minor for Viola and Piano, Op. 10 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 10. Moderato 9:59 11. Allegro agitato 6:28 12. L’istesso tempo ma poco rubato 4:24 Variations sur un air breton 13. Thème: Andante 1:06 14. Variation 1: L’istesso tempo poco rubato 1:39 15. Variation 2: Allegretto 1:06 16. Variation 3: Allegro patetico 1:10 17. Variation 4: Andante molto espressivo 1:23 18. Variation 5: Allegro con fuoco 1:18 19. Variation 6: Andante sostenuto 1:47 1 20. Variation 7: Fuga (Allegro moderato) 1:50 21. Coda: Poco più animato - Maestoso pesante 1:05 Total Time 71:02 In the early 20th century, composers Varvara Gaigerova, Alexander Winkler, and Paul Juon, reflect different aspects of Russian music at this historic time of intense social and political revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, in concert with the complex dynamics involved in the two great World Wars, created instability and hardship for most. -

ONYX4090 Cd-A-Bklt V8 . 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 Page 16:49 31/01/2012 V8

ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 p1 1 ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 2 Variations on a Russian folk song for string quartet (1898, by various composers) Variationen über ein russisches Volkslied Variations sur un thème populaire russe 1 Theme. Adagio 0.56 2 Var. 1. Allegretto (Nikolai Artsybuschev) 0.40 3 Var. 2. Allegretto (Alexander Scriabin) 0.52 4 Var. 3. Andantino (Alexander Glazunov) 1.25 5 Var. 4. Allegro (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) 0.50 6 Var. 5. Canon. Adagio (Anatoly Lyadov) 1.19 7 Var. 6. Allegretto (Jazeps Vitols) 1.00 8 Var. 7. Allegro (Felix Blumenfeld) 0.58 9 Var. 8. Andante cantabile (Victor Ewald) 2.02 10 Var. 9. Fugato: Allegro (Alexander Winkler) 0.47 11 Var. 10. Finale. Allegro (Nikolai Sokolov) 1.18 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 12 Russian Song 1.00 Russisches Lied · Mélodie russe p2 IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882–1971) 13 Concertino 6.59 ALFRED SCHNITTKE (1934–1998) 14 Canon in memoriam Igor Stravinsky 6.36 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 15 Old French Song 1.52 Altfranzösisches Lied · Mélodie antique française ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 3 16 Mama 1.32 17 The Hobby Horse 0.33 Der kleine Reiter · Le petit cavalier 18 March of the Wooden Soldiers 0.57 Marsch der Holzsoldaten · Marche des soldats de bois 19 The Sick Doll 1.51 Die kranke Puppe · La poupée malade 20 The Doll’s Funeral 1.47 Begräbnis der Puppe · Enterrement de la poupée 21 The Witch 0.31 Die Hexe · La sorcière 22 Sweet Dreams 1.58 Süße Träumerei · Douce rêverie 23 Kamarinskaya (folk song) 1.17 Volkslied · Chanson populaire p3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY String Quartet no.1 in D op.11 Streichquartett Nr. -

Lecture Slides

Lunch Lecture Inter-Actief will start at 12:50 ;lkj;lkj;lkj Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (orchestration: Maurice Ravel) Klaas Sikkel Münchner PhilharmonikerInter-Actief lunch conducted lecture, 15 Dec 2020 by Valery Gergiev 1 Pictures at an Exhibition and the Music of the Mighty Handful Inter-Actief Lunch Lecture 15 December 2020 Klaas Sikkel Muziekbank Enschede For Spotify playlist and more info see my UT home page (google “Klaas Sikkel”) Purpose of this lecture • Tell an entertaining story about a fragment of musical history • (hopefully) make you aware that classical music isn’t as boring as you thought, (possibly) raise some interest in this kind of music • Not a goal: make you a customer of the Muziekbank (instead, check out the Spotify playlist) Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 3 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) 4 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in Russia around 1860 Two persons have contributed greatly to professionalization and practice of Classical Music in Russia: • Anton Rubinstein (composer, conductor, pianist) • Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna (aunt of Tsar Alexander II, patroness) 5 Klaas Sikkel Inter-Actief lunch lecture, 15 Dec 2020 Classical Music in 1859 Russia around 1860 Founding of the Two persons have contributed Russian greatly to professionalization and Musical Society practice of Classical -

The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera

Not Russian Enough The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera R H ©?=>> Rutger Helmers Print production by F&N Boekservice Typeset using: LATEX ?" Typeface: Linux Libertine Music typesetting: LilyPond Not Russian Enough: The Negotiation of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Russian Opera Niet Russisch genoeg: nationalisme en de negentiende-eeuwse Russische operapraktijk (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) P ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magniVcus, prof. dr. G. J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag ? februari ?=>? des ochtends te >=.@= uur door Rutger Milo Helmers geboren op E november >FE= te Amersfoort Promotor: Prof. dr. E. G. J. Wennekes Co-promotor: Dr. M. V. Frolova-Walker Contents Preface · vii Acknowledgements · viii Preliminary Notes · x List of Abbreviations · xiii Introduction: The Part and the Whole · > Russia and the West · C The Russian Opera World · >= The Historiographical Legacy · >B Russianness RedeVned · ?> The Four Case Studies · ?A > A Life for the Tsar · ?F Glinka’s Changing Attitude to Italian Music · @@ The Italianisms of A Life for the Tsar · @F Liberties · BA Reminiscences · C> Conclusion · CB v vi CON TEN TS ? Judith · CD Serov the Cosmopolitan · D= Long-Buried Nationalities · E> Judith and Russianness · FE Conclusion · >=D @ The Maid of Orléans · >>> The Requirements of the Operatic Stage · >>C Schiller, The Maid, and Grand Opera Dramaturgy · >?> -

Miki Aoki – Biography

Piano Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Contents: Mailing Address: Biography 1000 South Denver Avenue Reviews Suite 2104 Repertoire Tulsa, OK 74119 Sample Programs Website: YouTube Video Links http://www.pricerubin.com Photo Gallery Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Miki Aoki – Biography Miki Aoki made her London Royal Festival Hall debut at the age of 12 and has since continued to perform in international venues. Recognized for her diverse abilities as pianist and as collaborative artist, Ms. Aoki balances her career performing solo recitals and chamber music, with working alongside young violinists. Ms. Aoki is currently appointed Senior lecturer at Graz University for Music and the Performing Arts, in Austria. Recent and upcoming highlights include a Japan tour with violinist Andrey Baranov and appearances at St. Petersburg Philharmonic Hall, the Copenhagen Chamber Music Festival and the Menuhin Festival in Gstaad. Miki Aoki is recording exclusively for German label Hänssler Profil. Her first CD of Zoltan Kodaly's piano works was released in the fall of 2011 to critical acclaim. BBC Music magazine called it “...a genuinely memorable performance.” The second CD, ‘The Belyayev Project’, featuring fascinating compositions varying from solo piano works by Liadov, Glazunov and Blumenfeld to the piano Trio by Rimsky-Korsakov was released in spring 2013. Recorded this January, her Miki Aoki – Biography third CD ‘Melancolie’ (solo piano works by Francis Poulenc and other Les Six composers) is planned for release in 2016. -

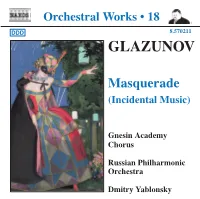

GLAZUNOV Masquerade

570211bk Glazunov US 8/5/09 16:23 Page 5 Gnesin Academy Chorus Dmitry Yablonsky The Gnesin Academy of Music is a State Institution in Moscow. Founded as a private music school by Elena, Dmitry Yablonsky was born in Moscow into a Orchestral Works • 18 Evgeniya and Mariya Gnesin in 1895, in 1920 it was divided into elementary school and secondary school, and later, musical family. His mother is the distinguished in 1944, became an Institute for Musical Education. The Academy adopted its present name in 1992, and includes pianist Oxana Yablonskaya, and his father Albert four schools, elementary school, ten-year primary school, secondary school and academy, with postgraduate Zaionz has for thirty years been principal oboist in DDD 8.570211 courses. The Gnesin Academy of Music includes a teaching staff of some four hundred, with over two thousand the Moscow Radio and Television Orchestra. Russian and foreign students. Dmitry began playing the cello when he was five and was immediately accepted by the Central Music School for gifted children. When he was nine he GLAZUNOV made his orchestral début as cellist and conductor Alexander Soloviev, Chorus-master with Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major. In Russia he studied with Stefan Kalianov, Rostropovich’s Alexander Soloviev was born in 1975 and studied at the Music School in Kostroma and at the Gnesin School. In assistant, and Isaak Buravsky, for many years solo 1995 he won first prize and special prize in the All-Russia Choral Conductors’ Competition and in 2001 took the cello of the Bolshoy Theatre Orchestra. -

A Tradição Continua Um Projeto Inovador

ANO 23 245 OUTUBRO 2018 www.clubedoaudioevideo.com.br ARTE EM REPRODUÇÃO ELETRÔNICA UM CONFORTO EXUBERANTE CÁPSULA MC MURASAKINO SUMILE E MAIS TESTE DE ÁUDIO CABO DE FORÇA TIMELESS MAGGINI A TRADIÇÃO CONTINUA ENTREVISTA AMPLIFICADOR INTEGRADO AUDIO ANDRÉ MEHMARI RESEARCH VSI75 OPINIÃO COMPRANDO LPS EM SEBOS E ESPECIALISTAS DE SÃO PAULO CDS CLÁSSICOS SCHUBERT: OBRAS SINFÔNICAS UM PROJETO INOVADOR CAIXAS ACÚSTICAS Q ACOUSTICS 3050I MUSICIAN: ROMANTISMO - NACIONALISMO NA MÚSICA II - ESCOLA RUSSA - VOL. 8 568146_TALENT_Semp Toshiba_215x270 29/08/2018 - 14:17 ÍNDICE TESTES DE ÁUDIO 30 Amplificador integrado Audio Research VSI75 CÁPSULA MC MURASAKINO SUMILE 22 36 Caixas acústicas Q Acoustics 3050i 42 Cabo de força Timeless EDITORIAL 4 Maggini Afinal, dá para ouvir gravações tecnicamente ruins em um sistema hi-end? DESTAQUES DO MÊS - MUSICIAN NOVIDADES 6 Bibliografia: a musicalidade russa 48 Grandes novidades das e o Orientalismo principais marcas do mercado 30 Bibliografia: Romantismo - 60 Nacionalismo na música II - EScola Russa HI-END PELO MUNDO 10 Novidades Romantismo - Nacionalismo II - 64 Escola Russa - Vol. 8 ENTREVISTA 12 André Mehmari, CDS CLÁSSICOS 68 multi-instrumentista e compositor Schubert: Obras sinfônicas OPINIÃO 14 ESPAÇO ABERTO 70 Comprando LPs em sebos e especia- 36 listas de são paulo Quanto mais sofisticado O sistema, mais arriscado É seu ajuste + SAIBA MAIS 16 Como manter seus LPs em bom estado ESPAÇO ABERTO 72 Tenho ouvidos para um sistema estado da arte? TESTES DE ÁUDIO 22 VENDAS E TROCAS 74 Cápsula MC Murasakino Excelentes oportunidades Sumile de negócios 42 OUTUBRO . 2018 3 EDITORIAL AFINAL, DÁ PARA OUVIR GRAVAÇÕES TECNICAMENTE RUINS EM UM SISTEMA HI-END? Fernando Andrette [email protected] Essa foi a pergunta que o filho de um grande amigo me fez, ao diferencial importante a todos que desejam um sistema hi-end, mas nos visitar recentemente e sentar com o seu pai para escutar música não abrem mão de ouvir todos os seus discos. -

MERCER-MCCOLLUM DUO Lydia Mercer, Viola

MERCER-MCCOLLUM DUO Lydia Mercer, viola. Ethan McCollum, piano. Midwest Tour, June 2019 Our Repertoire Program Notes by Jackson Harmeyer Hélène Fleury (1876-1957) The Mercer-McCollum Duo is passionate about playing Fantaisie, Op. 18 for viola and piano undiscovered, underplayed, and newly written gems of the viola-piano repertoire. This duo, including Lydia Byard Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936) Mercer, viola, and Ethan James McCollum, piano, is based Elégie in G minor, Op. 44 for viola and piano in Louisville, Kentucky and shares with audiences original music written for their distinctive instrumentation. Formed Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) in spring 2019 by these graduates of the University of Sonata in C minor, Op. 10 for viola and piano Louisville, the Duo launches their first concert tour this I. Moderato June as they share their discoveries with audiences across Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and upstate New York. Their II. Allegro agitato program features the music of three composers active at III. Variations sur un air breton the turn of the twentieth century—Hélène Fleury, Alexander Glazunov, and Alexander Winkler—each of whose music is tied to the Romantic tradition. Rich in its harmonic vibrancy, the relatively unknown viola-piano music of these three composers reveals an unfairly neglected realm still open to rediscovery. This music also reveals the idiomatic potential of the viola, apart from the commonplace transcriptions of violin and cello repertoire. We hope you will enjoy these selections and, through your voluntary support of our efforts, help us to revive more of this underappreciated repertoire! The career of Hélène Fleury (1876-1957) followed the pattern of so many female composers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: after tremendous successes in their youths, these women found themselves unable to pursue composition as a fulltime profession and their prodigious outputs quickly fell into neglect. -

Alexander Scriabin: Convergências E Divergências 54 Marcos Mesquita

LIA TOMÁS (Org.) SÉRIE PESQUISA EM MÚSICA NO BRASIL – VOLUME 6 FRONTEIRAS DA MÚSICA: FILOSOFIA, ESTÉTICA, HISTÓRIA & POLÍTICA 1ª edição São Paulo ANPPOM 2016 ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MÚSICA Diretoria 2015-2017 Sonia Regina Albano de Lima (UNESP), Presidente Martha Tupinambá de Ulhoa (UNIRIO), 1ª Secretária Fernando Lacerda Simões Duarte, 2º Secretário Marcos Fernandes Pupo Nogueira (UNESP), Tesoureiro Conselho Fiscal: José Augusto Mannis (UNICAMP), Titular Angela Elisabeth Luhning (UFBA), Titular Sonia Ray (UFG), Titular Lucyanne de Melo Afonso (UFAM), Suplente João Gustavo Kienen (UFAM), Suplente José Soares de Deus (UFU), Suplente Editora de Publicações da ANPPOM Marcos Holler (UDESC) FRONTEIRAS DA MÚSICA: FILOSOFIA, ESTÉTICA, HISTÓRIA & POLÍTICA SÉRIE PESQUISA EM MÚSICA NO BRASIL VOLUME 6 ANPPOM © 2016 os autores FRONTEIRAS DA MÚSICA: FILOSOFIA, ESTÉTICA, HISTÓRIA & POLÍTICA CAPA: XiloWeb (Verlaine Freitas) Reproduzido sob permissão FORMATAÇÃO E MONTAGEM João Paulo Costa do Nascimento Catalogação da Publicação Ficha catalográfica preparada pelo Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação do Instituto de Artes da UNESP F935 Fronteiras da música : filosofia, estética, história e política / organizadora, Lia Tomás. São Paulo : ANPPOM, 2016. 472 p. - (Série Pesquisa em Música no Brasil; v. 6) ISBN: 978-85-63046-05-5 1. Política. 2. Estética musical. 3. Filosofia da música. 4. História da música. I. Título. CDD 780.1 ANPPOM Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Música www.anppom.com Printed in Brazil 2016 -

Alexander Glazunov

FROM: AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE 890 Broadway New York, New York 10003 (212) 477-3030 Kelly Ryan ALEXANDER GLAZUNOV When Tchaikovsky died in 1893, Marius Petipa began to search for composers for his ballets. One of those to whom he turned was Alexander Glazunov, who was not yet thirty, but who had been one of the most gifted protégés of Rimsky-Korsakov and who already enjoyed a considerable international reputation. The results of their collaborations were three ballets: the three-act Raymonda in 1898, Glazunov’s first work for the theater, and Les Ruses d’amour and The Seasons, composed in 1898 and 1898, respectively, and produced in 1890, after which Glazunov composed nothing else for the theater. Glazunov was born in 1865 in St. Petersburg into a cultivated family. His talent was evident early, and he began to study the piano at age nine and to compose at age 11. In 1879, he met the composer Mily Balakirev who recommended studies with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, with whom his formal lessons advanced rapidly. At age 16, Glazunov completed his First Symphony, which received its premiere in 1882 led by Balakirev, followed by a performance of his First String Quartet. His talent gained the attention of the arts patron and amateur musician Mitrofan Belyayev, who championed Glazunov’s music, along with that of Rimsky-Korsakov, Anatoly Lyadov, among others, and took Glazunov on a tour of western Europe, during which he met Franz Liszt in Weimar. In 1889, Glazunov led a performance of his Second Symphony in Paris at the World Exhibition.