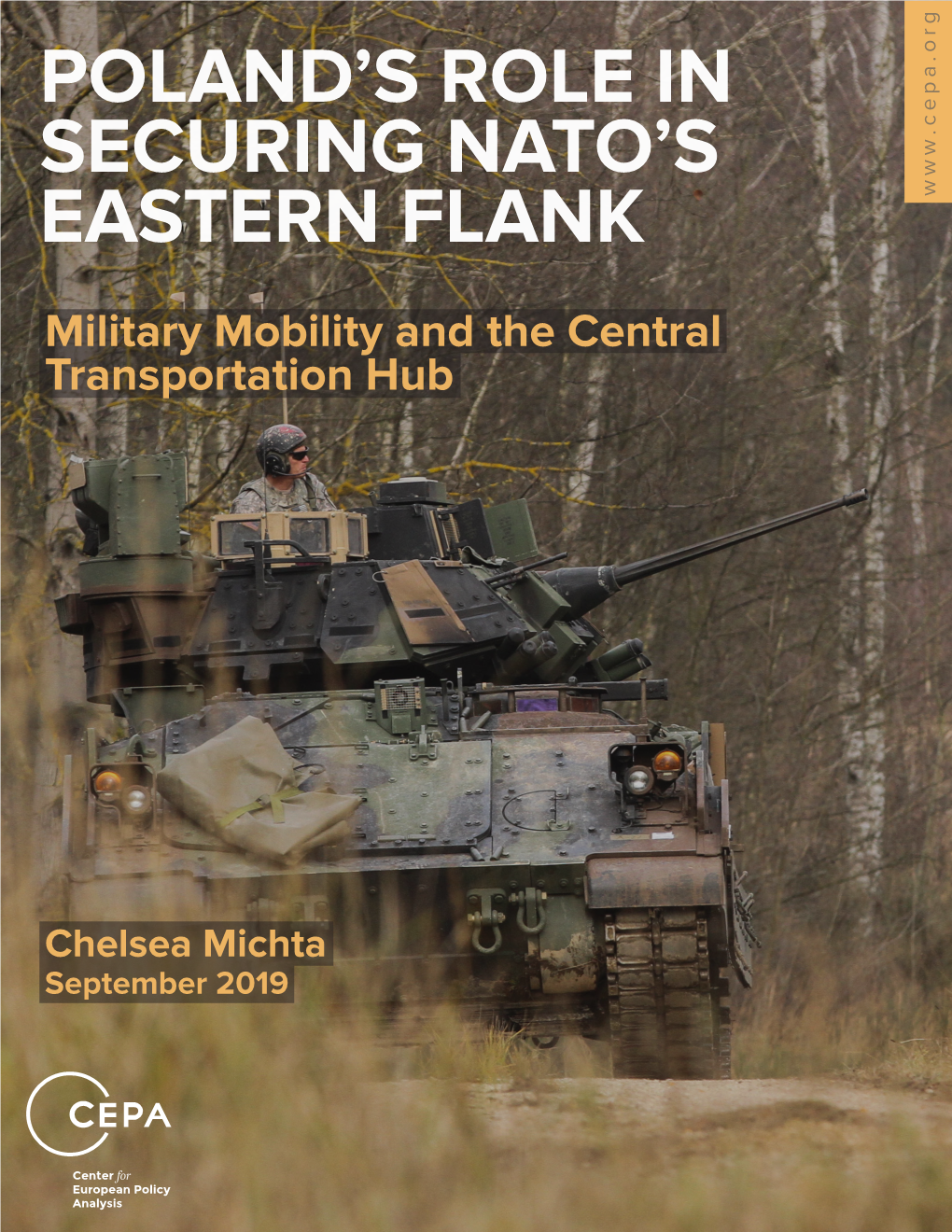

Poland's Role in Securing Nato's Eastern Flank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Belt and Road Meets the Three Seas Initiative

MAY 2020 MAY WARSAW China’s Belt and Road meets the Three Seas Initiative Chinese and US sticky power in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic ISBN 978-83-66306-74-5 and Poland’s strategic interests Warsaw, May 2020 Author: Grzegorz Lewicki Editing: Jakub Nowak, Małgorzata Wieteska Graphic design: Anna Olczak Graphic design cooperation: Liliana Gałązka, Tomasz Gałązka, Sebastian Grzybowski Polish Economic Institute Al. Jerozolimskie 87 02-001 Warsaw, Poland © Copyright by Polish Economic Institute ISBN 978-83-66306-74-5 Extended edition II 3 Table of contents Executive summary ...........................................4 Civilizations. The US, China and the Biblical logic of capitalism ...............7 Sticky power. China’s dream of a new Bretton Woods and the gravity of globalization...............................................12 Belt and Road. The dynamics of Confucian sticky power . 16 Three Seas. Where Belt and Road meets Bretton Woods ...................23 5G Internet. How digital geopolitics shapes the Three Seas' development...26 Poland. The Central Transport Hub and Three Sees Fund as gateways for the US and China .........................................29 The mighty sea of coronavirus. COVID-19 as a trigger of dappled globalisation ................33 A new perspective. Beyond the snipe and the clam ...............................36 Bibliography .................................................38 4 Executive Summary → The power of Western civilization seems political influence during the ongoing di- to be waning, in contrast to the power gital transformation of global economy. of Confucian civilization. After super- → Both China and the US effectively imposing civilizational identities in ac- use their sticky power; their ability to cordance with modern civilization theory shape the rules of globalization to their onto data from the In.Europa State Power benefit by projecting economic power Index, Confucian civilization (i.e. -

Accessibility of the Baltic Sea Region Past and Future Dynamics Research Report

Accessibility of the Baltic Sea Region Past and future dynamics Research report This report has been written by Spiekermann & Wegener Urban and Regional Research on the behalf of VASAB Secretariat at Latvian State Regional Development Agency Final Report, November 2018 Authors Tomasz Komornicki, Klaus Spiekermann Spiekermann & Wegener Urban and Regional Research Lindemannstraße 10 D-44137 Dortmund, Germany 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 2 Accessibility potential in the BSR 2006-2016 ........................................................................... 5 2.1 The context of past accessibility changes ........................................................................... 5 2.2 Accessibility potential by road ........................................................................................... 13 2.3 Accessibility potential by rail .............................................................................................. 17 2.4 Accessibility potential by air .............................................................................................. 21 2.5 Accessibility potential, multimodal ..................................................................................... 24 3. Accessibility to opportunities ................................................................................................... 28 3.1 Accessibility to regional centres ....................................................................................... -

LUBLIN DECLARATION on Establishment of the Economic Network of the Three Seas Regions *

LUBLIN DECLARATION on establishment of the Economic Network of the Three Seas Regions * Both Lublin and the Lubelskie Voivodeship have a unique place in the history of Europe. The Union of Lublin, signed in 1569, upon which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established, constitutes a positive example of the integration processes in European history. Having considered common the heritage, the history of the region and the concept of the THREE SEAS INITIATIVE, as well as the project of the Via Carpathia transit corridor, implemented under the INITIATIVE, we express our will to contribute to the joint building of the economic strength of Central and Eastern Europe, based on integrated and coordinated efforts aiming at the sustainable and responsible development of the individual regions within the European Union. Taking into account the implementation of the provisions already included in the Agreement for the construction of the Via Carpathia transit corridor, the signatories to this Declaration express their intention and will to act towards the establishment of a strong and permanent partnership for all the regions located in the area between the Baltic Sea, Adriatic Sea and Black Sea, covered by the Three Seas Initiative. The purpose of this agreement is to work together towards the development and reaping of the benefits by all societies of this area, and towards improvement of the regions' competitiveness at the European level. The establishment of the Economic Network of the Three Seas Regions, as a tool for the implementation of joint initiatives, will be an expression of enhanced interregional cooperation. Voivodeship represented by ………………………….. District represented by …………………………………. -

XENOPHON PAPER “Blue Growth As a Driver for Regional Development”

Matt eo Bocci, Frédérick Herpers, Thanos Smanis, Christophe Le Visage Thodoros E. Kampouris • Andrew Kennedy • Nataliia Korzhunova Emmanouil Nikolaidis • Natalia Zubchenko No16 XENOPHON PAPER “Blue Growth as a Driver for Regional Development” October 2018 2 XENOPHON PAPER no 16 The International Centre for Black Sea Studies (ICBSS) was founded in 1998 as a not-for-profit organisation. It has since fulfilled a dual function: on the one hand, it is an independent research and training institution focusing on the Black Sea region. On the other hand, it is a related body of the Organisation of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) and in this capacity serves as its acknowledged think-tank. Thus the ICBSS is a uniquely positioned independent expert on the Black Sea area and its regional cooperation dynamics. ___________________________________ The ICBSS launched the Xenophon Paper series in July 2006 with the aim to contribute a space for policy analysis and debate on topical issues concerning the Black Sea region. As part of the ICBSS’ independent activities, the Xenophon Papers are prepared either by members of its own research staff or by externally commissioned experts. While all contributions are peer-reviewed in order to assure consistent high quality, the views expressed therein exclusively represent the authors. The Xenophon Papers are available for download in electronic version from the ICBSS’ webpage under www.icbss.org. In its effort to stimulate open and engaged debate, the ICBSS also welcomes enquiries and contributions from its read- ers under [email protected]. XENOPHON PAPER no 16 3 Matt eo Bocci • Frédérick Herpers • Thanos Smanis • Christophe Le Visage Thodoros E. -

Językoznawstwo

JĘZYKOZNAWSTWO VIII PRACE NAUKOWE Akademii im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie FILOLOGIA POLSKA JĘZYKOZNAWSTWO VIII pod redakcją Marii Lesz-Duk Częstochowa 2012 Redaktor naukowy Maria LESZ-DUK Rada Naukowa Maria LESZ-DUK, Akademia im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie Kazimierz MICHALEWSKI, Uniwersytet Łódzki Feliks PLUTA, Uniwersytet Opolski Paweł PŁUSA, Akademia im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie Jana RACLAVSKA, Uniwersytet Ostrawski (Czechy) Dymitr STROWSKI, Uralski Uniwersytet Federalny w Jekaterynburgu (Rosja) Tetyana TYSZCZENKO, Państwowy Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Humaniu (Ukraina) Oksana ZELINSKA, Państwowy Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny w Humaniu (Ukraina) Redaktor tematyczny Mirosław ŁAPOT Redaktor naczelny wydawnictwa Andrzej MISZCZAK Korekta Paulina PIASECKA Redaktor techniczny Piotr GOSPODAREK Projekt okładki Sławomir SADOWSKI PISMO RECENZOWANE Nadesłane do redakcji artykuły są oceniane anonimowo przez dwóch recenzentów Podstawową wersją periodyku jest publikacja książkowa © Copyright by Akademia im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie Częstochowa 2012 ISBN 978-83-7455-297-4 ISSN 1896-0278 Wydawnictwo im. Stanisława Podobińskiego Akademii im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie 42-200 Częstochowa, ul. Waszyngtona 4/8 tel. (34) 378-43-29, faks (34) 378-43-19 www.ajd.czest.pl e-mail: [email protected] SPIS TREŚCI ARTYKUŁY Anna ADAMEK Najpopularniejsze imiona nadawane w gminie Koszęcin w latach 2000–2009 ...................................................................................... 9 Renata BIZIOR Z prywatnej korespondencji Jędrzeja Kitowicza -

Guidelines for Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians

Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Part of Output 3.2 Planning Toolkit TRANSGREEN Project “Integrated Transport and Green Infrastructure Planning in the Danube-Carpathian Region for the Benefit of People and Nature” Danube Transnational Programme, DTP1-187-3.1 April 2019 Project co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) www.interreg-danube.eu/transgreen Authors Václav Hlaváč (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, Member of the Carpathian Convention Work- ing Group for Sustainable Transport, co-author of “COST 341 Habitat Fragmentation due to Trans- portation Infrastructure, Wildlife and Traffic, A European Handbook for Identifying Conflicts and Designing Solutions” and “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Petr Anděl (Consultant, EVERNIA s.r.o. Liberec, Czech Republic, co-author of “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Jitka Matoušová (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic) Ivo Dostál (Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic) Martin Strnad (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, specialist in ecological connectivity) Contributors Andriy-Taras Bashta (Biologist, Institute of Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Science in Ukraine) Katarína Gáliková (National -

Information About the Meeting of the General Committee on Economic

Information about the Meeting of the General Committee on Economic Affairs of the Central European Initiative Parliamentary Dimension held in Warsaw on 25 September 2018. On 25 September 2018, the Meeting of the General Committee on Economic Affairs of the Parliamentary Dimension of the Central European Initiative was held in Warsaw. Delegations from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine and Hungary participated in the meeting. The Belarusian delegation was represented by a representative of this country's Embassy in Warsaw. The meeting was chaired by Bogdan Rzońca, MP - Head of the Polish Parliamentary Delegation to the CEI and Chairman of the General Committee on Economic Affairs. The main topic of the meeting was Infrastructure, road and energy, connections in the Central European Initiative region on the North – South axis, with special focus on Via Carpathia road construction project. The welcome address to the participants was given by Marek Kuchciński, Marshal of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland. The following persons participated in the meeting on behalf of the Polish government: Andrzej Adamczyk, Minister of Infrastructure, Krzysztof Tchórzewski, Minister of Energy, as well as representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Investment and Development. In the course of the debate, it was emphasized that the aim of regional cooperation in the scope of the development of infrastructure should be the creation of a cohesive transport system between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea as well as the Balkans. One of the main projects in this scope is Via Carpatia. It is expected that its construction will facilitate and speed up further economic development of the countries of the region, enabling an increase in the quality of life and wealth of the residents. -

D. Héjj, the Three Seas Initiative in the Foreign Affairs Policy of Hunga- Ry, „Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej” 17 (2019), Z

Vol. 17 (2019) Vol. Yearbook Yearbook Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej of the Institute of the Institute of East-Central Europe of East-Central Europe (Yearbook of the Institute of East-Central Europe) Volume 17 (2019) Volume 17 (2019) Issue 3 Issue 3 of East-Central Europe of East-Central the Institute of Yearbook ISSN 1732-1395 The Three Seas Initiative (TSI) is a fl exible political platform, at Presidential level, launched in 2016 in Dubrovnik (Croatia). The Initiative includes the 12 EU Member States located between the Adriatic, the Baltic and the Black Seas: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia Instrukcje dla autorów i Rocznik online: and Slovenia. Countries that have decided to join the Three Seas project have a common geographical, historical and political identity. The pillar of the TSI are countries belonging to the Visegrad Group. Presidents of TSI member countries meet at annual summits. The summits so far have taken place in Dubrovnik (2016) Warsaw (2017), Bu- 3 Rocznik Instytutu Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej https://ies.lublin.pl/rocznik charest (2018) and Ljubljana (2019). The next summit will be held in Tallinn. Rok 17 (2019), Zeszyt 3 Łukasz Lewkowicz, s. 7-8 Perspective the International in Initiative Seas Three The The origins of the TSI are to be found in the Polish geopolitical representations that emerged in the 1920s after The Three Seas Initiative the First World War, specifi cally, Josef Pilsudski’s Intermarium (Latin for the Polish Międzymorze). The ideas of this old project have resurfaced in the current geopolitical confi guration. -

The Three Seas Initiative: Configuration and Global Geopolitical Consequences

Opinion Paper 48/2021 26/04/2021 Óscar Méndez Pérez* The Three Seas Initiative: Visit Web Receive Newsletter Configuration and Global Geopolitical Consequences The Three Seas Initiative: Configuration and Global Geopolitical Consequences Abstract: The Three Seas Initiative (3SI) is an alliance of Central and Eastern European countries located among the Baltic, Black and Adriatic Seas. Its objectives focus on achieving an interconnected region, with a north-south approach, in the fields of energy, infrastructure and telecommunications. At the same time, it has an eminent geopolitical component that not only can be felt in the region, but that also involves the four major world powers: the US, Russia, China and the European Union. Keywords: Three Seas Initiative, geopolitics, Central and Eastern Europe, energy, infrastructures, telecommunications. How to quote: MÉNDEZ PÉREZ, Óscar. The Three Seas Initiative: Configuration and Global Geopolitical Consequences. Opinion Paper. IEEE 48/2021. http://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2021/DIEEEO48_2021_OSCMEN_Tresmares _ENG.pdf and/or link bie3 (accessed on the web day/month/year) *NOTE: The ideas contained in the Opinion Papers shall be responsibility of their authors, without necessarily reflecting the thinking of the IEEE or the Ministry of Defense. Opinion Paper 48/2021 1 The Three Seas Initiative: Configuration and Global Geopolitical Consequences Óscar Méndez Pérez Introduction The Three Seas Initiative (TSI) is a collaborative platform between Poland, Croatia, Austria, Bulgaria, -

Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society

Prace Komisji Geografii Przemysłu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego kwartalnik naukowy Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society a scientific quarterly PRZEMIANY SEKTORA USŁUG TRANSPORTOWYCH I TURYSTYCZNYCH pod redakcją Zbigniewa Zioło i Tomasza Rachwała THE TRANSFORMATION OF TRANSPORT AND TOURISM INDUSTRY edited by Zbigniew Zioło and Tomasz Rachwał 30(4) · 2016 Polskie Towarzystwo Geograficzne – Komisja Geografii Przemysłu Polish Geographical Society – Industrial Geography Commission Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. Komisji Edukacji Narodowej w Krakowie – Instytut Geografii PRACEPedagogical KOMISJI University GEOGRAFII of Cracow PRZEMYSŁU – Institute of Geography POLSKIEGO TOWARZYSTWA GEOGRAFICZNEGO STUDIES OF THE INDUSTRIAL GEOGRAPHY COMMISSION OF THE POLISH GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY 30(4) Redaktor naczelny / Editor-in-chief: Zastępca redaktora naczelnego – redaktor Zbigniew prowadzący Zioło / Associate – managing editor: Rada Redakcyjna / Editorial Board Tomasz Rachwał Rada Redakcyjna / Editorial Board Zoltán Bartha, Bernard Bińczycki, Krzysztof Borodako, Paweł Czapliński, Anna Czaplińska-Kibycz, Joanna Dominiak, LiudmilaPaweł Czapliński, Fakeyeva, Wiesława Roman Fedan, Gierańczyk, Hanna AnatolGodlewska-Majkowska, Jakobson, Wioletta Bronisław Kilar, Ana Górz, María Bartosz Liberali, Jenner, Tadeusz Andrea Marszał, Gubik, MikhailoTomasz Rachwał Hamkalo, (wiceprzewodniczący/vice-chair), Jerzy Kitowski, Arkadiusz Kołoś, Tomasz Eugeniusz Komornicki, Rydz, Tadeusz Sławomir Stryjakiewicz, Kurek, René Anatoly -

Segment Komunikacyjny

Segment komunikacyjny 1 Spis treści 1. Polityka obsługi komunikacyjnej 5. Koncepcja układu komunikacyjnego 1.1 Cele i środki realizacji 5.1 Analiza i ocena potencjalnych lokalizacji P&R 1.2 Preferencje dojazdu do Wystawy w podziale na rodzaj transportu 5.2 Lokalizacja istniejących parkingów wspierających Istniejące powiązania komunikacyjne w skali kraju i regionu oraz potencjalny 5.3 Łódzka Kolej Aglomeracyjna 2. rozwój sieci połączeń 5.4 Dworzec Łódź Fabryczna 2.1 Powiązania komunikacyjne w skali kraju i regionu 5.5 Miejski transport publiczny 2.2 Dostępność komunikacyjna Łodzi w zależności od czasu dojazdu 5.6 Ocena systemu transportowego w rejonie Wystawy 2.3 Powiązania komunikacyjne na poziomie lokalnym 5.7 Obsługa komunikacyjna w rejonie Wystawy 2.4 Analiza lokalnej bazy hotelowej 5.8 Obsługa komunikacyjna na terenie Wystawy 3. Prognozy ruchu Zwiedzających w dniach szczytowych 5.9 Inwestycje infrastrukturalne 3.1 Prognozowana liczba odwiedzin 5.10 Wykaz działań instytucjonalnych, organizacyjnych i prawnych 3.2 Prognozowana liczba osób korzystających z bazy hotelowej 6. Plan mobilności 3.3 Opis podziału zadań przewozowych 3.4 Podział zadań przewozowych w dniu szczytowym 4. Model ruchu 2 Cel i zakres opracowania Celem niniejszego raportu jest przedstawienie wyników analiz oraz prac projektowych związanych z zapewnieniem efektywnego poziomu obsługi komunikacyjnej podczas trwania Wystawy Expo Horticultural 2024 w Łodzi. Główne założenie koncepcji komunikacyjnej przewiduje maksymalne ograniczenie ruchu kołowego generowanego przez Zwiedzających Wystawę, w taki sposób, aby nie dopuścić do nadmiernych kongestii w wewnątrzmiejskiej sieci ulicznej. Zamysł ten ma na celu zatrzymanie ruchu samochodowego na obrzeżach miasta oraz zapewnienie łatwego dostępu dla Zwiedzających Wystawę za pomocą alternatywnych środków transportu. -

Economic Openness

GLOBAL INDEX OF ECONOMIC OPENNESS Economic Openness Romania Case Study 2019 CREATING THE PATHWAYS FROM POVERTY TO PROSPERITY ABOUT THE LEGATUM INSTITUTE The Legatum Institute is a London-based think tank with a global vision: to see all people lifted out of poverty. Our mission is to create the pathways from poverty to prosperity, by fostering Open Economies, Inclusive Societies and Empowered People. We do this in three ways: Our Centre for Metrics which creates indexes and datasets to measure and explain how poverty and prosperity are changing. Our Research Programmes which analyse the many complex drivers of poverty and prosperity at the local, national and global level. Our Practical Programmes which identify the actions required to enable transformational change. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Stephen Brien is Director of Policy at the Legatum Institute. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Helen Slater, Bianca Swalem, Hugh Carveth, Daniel Herring, and Edward Wickstead for their contributions to this work. This report was prepared as briefing for the Aspen Europe Next conference, held in Bucharest. This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc. The opin- ions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc. The Legatum Institute would like to thank the Legatum Foundation for their sponsorship. Learn more about the Legatum Foundation at www.legatum.org ©2019 The Legatum Institute Foundation. All rights reserved. The word ‘Legatum’ and the Legatum charioteer logo are the subjects of trade mark registrations of Legatum Limited is a registered trade mark of Legatum Foundation Limited.