Science, Humanity, Alan Alda, and the Quest for Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of introducing each Screen Actors Guild Awards telecast with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I Am an Actor™." So far, audiences have been delighted by 107 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

Larry Groupe- Biography

Jack Price Founding Partner / Managing Director Marc Parella Partner / Director of Operations Mailing Address: 520 Geary Street Suite 605 San Francisco CA 94102 Telephone: Toll-Free 1-866-PRI-RUBI (774-7824) 310-254-7149 / Los Angeles 415-504-3654 / San Francisco Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: http://www.pricerubin.com Yahoo!Messenger pricerubin Contents: Biography Critical Acclaim Credits IMDB Credits Film Lecture Syllabus Larry Groupe- Biography Larry Groupé is one of the most talented and versatile composers working today in the entertainment industry. With an impressive musical résumé in film and television as well as the concert stage, his achievements have received both critical praise and popular acclaim. Larry has completed his latest score for Straw Dogs. Directed by Rod Lurie starring James Marsden, Kate Bosworth and Alexander Skarsgård. Just prior to this was Nothing but the Truth starring Kate Beckinsale, Matt Dillon and Alan Alda. A compelling political drama about first amendment rights. Which followed on the heels of Resurrecting the Champ starringSamuel L. Jackson and Josh Hartnett. All collaborations with writer-director Rod Lurie. Most notably, he wrote the score for The Contender starring Joan Allen, Gary Oldman and Jeff Bridges, a highly regarded political drama written and directed by Rod Lurie, which received multiple Academy Award nominations. This political drama edge led them toCommander in Chief, which became the number one most successful new TV series when launched by ABC. Larry also enjoyed special recognition when he teamed with the Classic Rock legends, YES, co-composing ten original songs on the new CD release, Magnification, as well as writing overtures, arrangements and conducting the orchestra on their Symphonic Tour of the World. -

Word Search 'Crisis on Infinite Earths'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! December 6 - 12, 2019 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H W Q A R C F E B M R A L Your Key 2 x 3" ad O R F E I G L F I M O E W L E N A B K N F Y R L E T A T N O To Buying S G Y E V I J I M A Y N E T X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad U I H T A N G E L E S G O B E P S Y T O L O N Y W A L F Z A T O B R P E S D A H L E S E R E N S G L Y U S H A N E T B O M X R T E R F H V I K T A F N Z A M O E N N I G L F M Y R I E J Y B L A V P H E L I E T S G F M O Y E V S E Y J C B Z T A R U N R O R E D V I A E A H U V O I L A T T R L O H Z R A A R F Y I M L E A B X I P O M “The L Word: Generation Q” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bette (Porter) (Jennifer) Beals Revival Place your classified ‘Crisis on Infinite Earths’ Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Shane (McCutcheon) (Katherine) Moennig (Ten Years) Later ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Alice (Pieszecki) (Leisha) Hailey (Los) Angeles 1 x 4" ad (Sarah) Finley (Jacqueline) Toboni Mayoral (Campaign) County Trading Post! brings back past versions of superheroes Deal Merchandise Word Search Micah (Lee) (Leo) Sheng Friendships Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item Brandon Routh stars in The CW’s crossover saga priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 “Crisis on Infinite Earths,” which starts Sunday on “Supergirl.” for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Printable Oscar Ballot

77th Annual ACADEMY AWARDS www.washingtonpost.com/oscars 2005 NOMINEES CEREMONY: Airs Sunday, February 27, 2005, 8p.m. EST / ABC BEST PICTURE ACTOR ACTRESS “The Aviator” Don Cheadle ("Hotel Rwanda") Annette Bening ("Being Julia") Johnny Depp ("Finding Neverland") Catalina Sandino Moreno ("Maria “Finding Neverland” Full of Grace") “Million Dollar Baby” Leonardo DiCaprio ("The Aviator") Imelda Staunton ("Vera Drake") Clint Eastwood ("Million Dollar Hilary Swank ("Million Dollar “Ray” Baby") Baby") Kate Winslet ("Eternal Sunshine of “Sideways” Jamie Foxx ("Ray") the Spotless Mind") ★ ★ 2004 WINNER: "The Lord of the ★ 2004 WINNER: Sean Penn, "Mystic 2004 WINNER: Charlize Theron, Rings: The Return of the King" River" "Monster" DIRECTOR SUPPORTING ACTOR SUPPORTING ACTRESS Martin Scorsese (”The Aviator”) Alan Alda (”The Aviator”) Cate Blanchett (”The Aviator”) Thomas Haden Church Clint Eastwood (”Million Dollar Laura Linney (”Kinsey”) Baby”) (”Sideways”) Jamie Foxx (”Collateral”) Taylor Hackford (”Ray”) Virginia Madsen (”Sideways”) Morgan Freeman (”Million Dollar Sophie Okonedo (”Hotel Rwanda”) Alexander Payne (”Sideways”) Baby”) Mike Leigh (”Vera Drake”) Clive Owen “Closer”) Natalie Portman (”Closer”) ★ 2004 WINNER: Peter Jackson, "The ★ 2004 WINNER: Tim Robbins, "Mystic ★ 2004 WINNER: Renee Zellweger, Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" River" "Cold Mountain" ANIMATED FEATURE ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY ADAPTED SCREENPLAY “The Incredibles” “ The Aviator” “Before Sunset” “Shark Tale” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless “Finding Neverland” Mind” “Shrek 2” “Hotel Rwanda” “Million Dollar Baby” “The Incredibles” “The Motorcycle Diaries” “Vera Drake” “Sideways” ★ 2004 WINNER: "Finding Nemo" ★ 2004 WINNER: "Lost in Translation" ★ 2004 WINNER: "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King" 1 77th Annual ACADEMY AWARDS www.washingtonpost.com/oscars 2005 NOMINEES CEREMONY: Airs Sunday, February 27, 2005, 8p.m. -

Frank Ferrante Reprises His Acclaimed “An Evening with Groucho” at Bucks County Playhouse As Part of Visiting Artists Program • February 14 – 25, 2018

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: FHPR – 215-627-0801 Sharla Feldscher, #101, cell 215-285-4868, [email protected] Hope Horwitz, #102, cell 215-760-2884, [email protected] Photos of Frank Ferrante visiting former home of George S. Kaufman, now Inn of Barley Sheaf Farm: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/70z5e7y6b1p4odd/AAAAw4xwq7EDYgBjcCxCf8p9a?dl=0 Photos by Sharla Feldscher “GROUCHO” RETURNS TO NEW HOPE! Frank Ferrante Reprises His Acclaimed “An Evening with Groucho” at Bucks County Playhouse as part of Visiting Artists Program • February 14 – 25, 2018 Special Preview was Feb. 12, 2018 when Ferrante visited Inn of Barley Sheaf Farm in Bucks County, the former home of Playwright George S. Kaufman where Marx Brothers visited often. New Hope, PA (February 14, 2018) – The quick-witted American actor and icon, Groucho Marx was a frequent visitor to New Hope and Bucks County. Now nearly 41 years after his death, Groucho makes a hilarious return to Bucks — this time in the form of award-winning actor Frank Ferrante in the global comedy hit, “An Evening with Groucho.” The show is presented February 14 – 25 at Bucks County Playhouse as part of the 2018 Visiting Artists Series. As a special preview, Mark Frank, owner of The Inn at Barley Sheaf Farm, invited Frank Ferrante, the preeminent Groucho Marx performer, and press on a tour of this historic former home of Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright, George S. Kaufman. The duo provided insight into the farm’s significance and highlighted Groucho’s role in Bucks County’s rich cultural history. Amongst the interesting facts shared on the preview, Ferrante told guests: • George S. -

To Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! July 2 - 8, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: Phil Keoghan THE LINKS! The latest 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 hosts “Tough as house and Jacksonville Beach homes listings Nails,” premiering Page 21 Wednesday on CBS. Offering: · Hydrafacials Getting ‘Tough’- · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Phil Keoghan hosts and · B12 Complex / produces new CBS series Lipolean Injections Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN Phil Keoghan gives CBS a T competition What’s Available NOW On When Phil Keoghan created “Tough as Nails,” he didn’t foresee it being even more apt by the time it aired. -

Hallmark Collection

Hallmark Collection 20000 Leagues Under The Sea In 1867, Professor Aronnax (Richard Crenna), renowned marine biologist, is summoned by the Navy to identify the mysterious sea creature that disabled the steamship Scotia in die North Atlantic. He agrees to undertake an expedition. His daughter, Sophie (Julie Cox), also a brilliant marine biologist, disguised as a man, comes as her father's assistant. On ship, she becomes smitten with harpoonist Ned Land (Paul Gross). At night, the shimmering green sea beast is spotted. When Ned tries to spear it, the monster rams their ship. Aronnax, Sophie and Ned are thrown overboard. Floundering, they cling to a huge hull which rises from the deeps. The "sea beast" is a sleek futuristic submarine, commanded by Captain Nemo. He invites them aboard, but warns if they enter the Nautilus, they will not be free to leave. The submarine is a marvel of technology, with electricity harnessed for use on board. Nemo provides his guests diving suits equipped with oxygen for exploration of die dazzling undersea world. Aronnax learns Nemo was destined to be the king to lead his people into the modern scientific world, but was forced from his land by enemies. Now, he is hoping to halt shipping between the United States and Europe as a way of regaining his throne. Ned makes several escape attempts, but Sophie and her father find the opportunities for scientific study too great to leave. Sophie rejects Nemo's marriage proposal calling him selfish. He shows his generosity, revealing gold bars he will drop near his former country for pearl divers to find and use to help the unfortunate. -

An Insider's Guide to Hollywood Politics-How the Top Forty Stars Route Their Clout

An insider'sguide to Hollywoodpolitics-how the top forty stars route their clout. A,ound Tinseltown,the game's catted Sta, Warno, HottYfics.BYWhate,e, FRANK the tabet,BIES no one's deny;ng the su,p,ise ,esu,gence of pofificat acfiWsm"°"nd lhe Hott,wooa Hms.Roben Redto,d stomps fo, <edwooas.Pam Dawbe, P<eaches sofa, ene,gy. Syt>este,Stattone goes ten ,ounds the United Way. The big charifies-.oance,, heart, tung, muscufa, dyst,ophy, mufl/pfescte<osis-<1ow boast tong waifing fists of ceteb c,usade,s eage, lo hetp cid lhe WOrldof disease. Pottlicat,affies featu,e sla,·sludded casts Iha, focus sombe, attention on abused Chitd,en(Cheryl Ladd's ma;o, cause), oif monopofies (Wa,,en Beatty's), o, nuclea, disa,mamen, (PautNewman's). Few se/f-,especfingsta,s woufd appea, on lhe lafk show cfrcuil these days Withoutdenouncing the e,its ! of strip miningor espousingthe wondersof Easter Seats. 75 Of course, politics and Hollywood have wood, a porpoise from a purpose, and are cal Aid to El Salvador. Noted for calllP.g never been total strangers. As far back as primarily motivated by that great god, adversary Charlton Heston a "c,Q._ck D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, film Publicity. But the majority harbor varying sucker" and "scumbag," respective1y. evinced its power to stir up the social con degrees of commitment and sophistica Lost decisive battle with Heston over science. The influence cuts both ways: tion on issues that range from handguns to union merger between Screen Actors and during the Hollywood Dark Ages, the Hanoi. -

Betsy's Wedding

Betsy’s Wedding ½ Year of Release: 1990 Review by Randy Parker Country: USA Verdict: See It One of my colleagues was surprised when I told story of culture clash, or as one character puts it, her I was willing to see Betsy’s Wedding . And she “money versus values.” was shocked to hear that I actually liked it. Her Sheedy, in a wonderfully understated perfor- reaction was understandable when you consider mance, is one of the film’s most pleasant surprises. that the film revolves around Molly Ringwald, Sheedy expresses more with just her eyes than who hasn’t made a worthwhile film since 1986. Ringwald does with her entire body. It’s Anthony But the fact is, Betsy’s Wedding also is an Alan Alda LaPaglia, however, who seizes the spotlight. film. And while Ringwald has been making duds LaPaglia plays Stevie Dee, a suave, overly polite for the last four years, Alda has been involved Mafioso who is formally courting Sheedy with with several noteworthy projects, including Crimes old-fashioned chivalry. LaPaglia’s sincere but and Misdemeanors and A New Life . dim-witted character is a riot. And what’s uncan- Written and directed by Alda, Betsy’s Wedding is ny is that LaPaglia is a dead ringer for Robert De a vibrant slice-of-life, mixing a few dramatic mo- Niro, with a little bit of Alec Baldwin thrown in ments into a big bowl of whimsical humor. Alda’s for good measure. LaPaglia seems to have attend- comic elixir is smooth and refreshing and a wel- ed the De Niro school of gangster acting, and his come change of pace from the usual summer fare. -

Will Locals Fare Well in Oscar Race?

SECTION INSIDE: People Malibu Seen B Classified The Malibu Times February 3, 2005 L ife & Arts Feature Editor: Laura Tate Malibu’s Top Ten Books Will locals fare well in Oscar race? e now return to the “normal” with purchases mostly for personal reading, less of the gift-giving books of the holi- Tune in and take your Wdays. pick. Due to word-of-mouth bookseller recommendations, new media attention and book clubs, many books continue their long By Andrew Lyons runs on Diesel’s bestseller lists: “Kite Runner,” “Devil in the White Special to The Malibu Times City” and “Dylan’s Chronicles.” For children, a bestseller of recent years has catapulted back to ominations for the 77th the No. 1 spot due to the new movie version of it—”Because of Annual Academy Awards Winn-Dixie.” “Egyptology,” the hot book for the holidays, contin- Nwere announced last ues its strong sales, a wonderful book for children of all ages. And month and with only a few weeks “Fever, 1793” is a strong historical novel, recommended by teachers until the Feb. 27 telecast, it’s time and read by at least one mother-daughter book club in Malibu. to get down to business. We’re For adults, Malcolm Gladwell, author of “Tipping Point,” is here to help you get a jump on the making the media rounds and, coupled with excellent pre-publica- office pool fun with our predictions tion reviews, is blasting out the door with his new book, “Blink.” of who will win and more impor- Also, in nonfiction the new one by the author of “Guns, Germs tantly, who should win. -

HIFF-2016-Open-For-Submissions.Pdf

The Hamptons International Film Festival Open For Film Submissions Approved as an Academy Qualifying Festival for the Documentary Short Subject Award The 24th Annual Hamptons International Film Festival takes place from October 6th-10th, 2016 February 22nd, 2016, New York, NY— The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) today announced the opening of its annual film submission process. It also announced that it is now an Academy qualifying festival for the Documentary Short Subject Award. With four competitive categories in narrative feature, documentary feature, narrative short film, documentary short film, and programs in seven non-competitive categories, the Hamptons International Film Festival seeks diverse films made by filmmakers that traverse the globe in order to tell their stories through different cultural styles and experiences. Already an Academy qualifying festival for Short Live Action Films, the HIFF can now grant the winner of its Documentary Short Film Competition eligibility to enter the Documentary Short Subject category of the Academy Awards® without standard theatrical run. This is provided the film otherwise complies with the Academy rules which can be found at www.oscars.org/rules. In 2015, three of this year's Oscar nominated short documentaries were screened at HIFF (CLAUDE LANZMANN: SPECTRES OF THE SHOAH, BODY TEAM 12, and LAST DAY OF FREEDOM). Last year also saw a record number of submissions for the festival, and 36 Oscar nominations from films that played throughout all categories. The HIFF's 2015 attendees included Alan Alda, Emily Blunt, Liev Schreiber, Josh Charles, Morgan Freeman, Tom McCarthy, John Slattery, Michael Moore, Dennis Quaid, Jacob Tremblay, Charlie Kaufman, Bel Powley, Keith Stanfield, Chris Abbot, Phyllis Nagy, Alec Baldwin, Todd Haynes, Thomas Mann, Dan Rather, James Vanderbilt, Olivia Wilde, Bobby Flay and many more. -

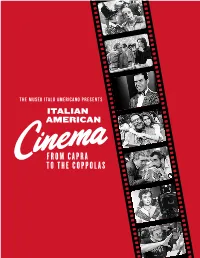

Cinema-Booklet-Web.Pdf

1 AN ORIGINAL EXHIBITION BY THE MUSEO ITALO AMERICANO MADE POSSIBLE BY A GRANT FROM THE WRITTEN BY Joseph McBride CO-CURATED BY Joseph McBride & Mary Serventi Steiner ASSISTANT CURATORS Bianca Friundi & Mark Schiavenza GRAPHIC DESIGN Julie Giles SPECIAL THANKS TO American Zoetrope Courtney Garcia Anahid Nazarian Fox Carney Michael Gortz Guy Perego Anne Coco Matt Itelson San Francisco State University Katherine Colridge-Rodriguez Tamara Khalaf Faye Thompson Roy Conli The Margaret Herrick Library Silvia Turchin Roman Coppola of the Academy of Motion Walt Disney Animation Joe Dante Picture Arts and Sciences Research Library Lily Dierkes Irene Mecchi Mary Walsh Susan Filippo James Mockoski SEPTEMBER 18, 2015 MARCH 17, 2016 THROUGH THROUGH MARCH 6, 2016 SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 Fort Mason Center 442 Flint Street Rudolph Valentino and Hungarian 2 Marina Blvd., Bldg. C Reno, NV 89501 actress Vilma Banky in The Son San Francisco, CA 94123 775.333.0313 of the Sheik (1926). Courtesy of United Artists/Photofest. 415.673.2200 www.arteitaliausa.com OPPOSITE: Exhibit author and www.sfmuseo.org Thursdays through co-curator Joseph McBride (left) Tuesdays through Sundays 12 – 4 pm Sundays 12 – 5 pm with Frank Capra, 1985. Courtesy of Columbia Pictures. 2 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Italian American Cinema: From Capra to the Coppolas 6 FOUNDATIONS: THE PIONEERS The Long Early Journey 9 A Landmark Film: The Italian 10 “Capraesque” 11 The Latin Lover of the Roaring Twenties 12 Capra’s Contemporaries 13 Banking on the Movies 13 Little Rico & Big Tony 14 From Ellis Island to the Suburbs 15 FROM THE STUDIOS TO THE STREETS: 1940s–1960s Crooning, Acting, and Rat-Packing 17 The Musical Man 18 Funnymen 19 One of a Kind 20 Whaddya Wanna Do Tonight, Marty? 21 Imported from Italy 22 The Western All’italiana 23 A Woman of Many Parts 24 Into the Mainstream 25 ANIMATED PEOPLE The Golden Age – The Modern Era 26 THE MODERN ERA: 1970 TO TODAY Everybody Is Italian 29 Wiseguys, Palookas, & Buffoons 30 A Valentino for the Seventies 32 Director Frank Capra (seated), 1927.