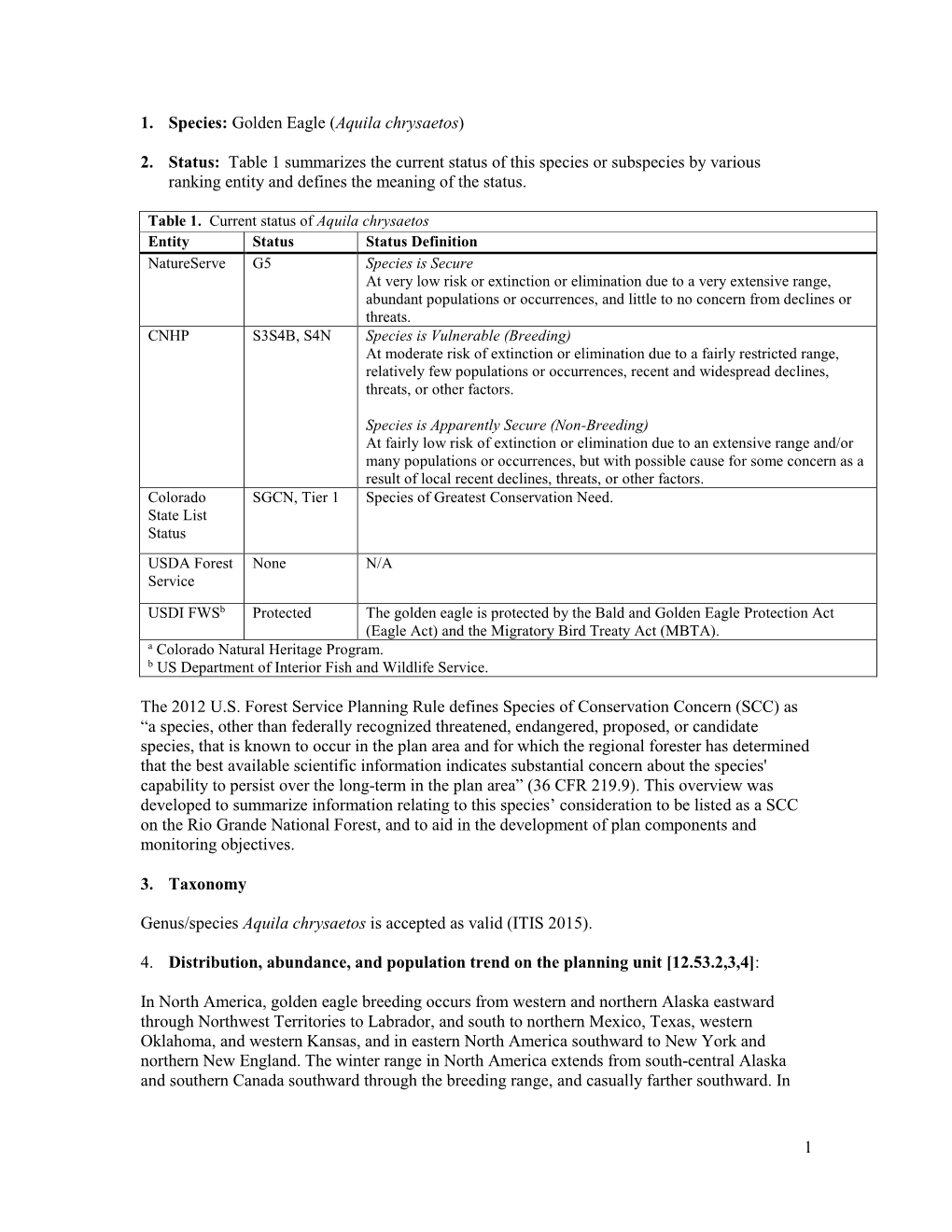

1 1. Species: Golden Eagle (Aquila Chrysaetos) 2. Status: Table 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Status of the Eastern Imperial Eagle (Aquila Heliaca) in the European Part of Turkey

ACTA ZOOLOGICA BULGARICA Acta zool. bulg., Suppl. 3, 2011: 87-93 Status of the Eastern Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca) in the European part of Turkey Dimitar A. Demerdzhiev1, Stoycho A. Stoychev2, Nikolay G. Terziev2, and Ivaylo D. Angelov2 1 31 Bulgaria Blv�., 4230 Asenovgra�, Bulgaria; E�mails: �emer�jiev@yahoo.�om; �_�emer�[email protected]; w��.bspb.org 2 Haskovo 6300, P.O.Box 130, Bulgaria; E�mails: stoy�hev.s@gmail.�om; w��.bspb.org; [email protected]; ivailoange� [email protected]; w��.bspb.org Abstract: This arti�le presents the results of the �rst more �etaile� stu�ying on the �istribution an� numbers of the Eastern Imperial Eagle (Аquila heliaca SA V I G NY 1809) population in the European part of Turkey. T�enty territories o��upie� by Imperial Eagle pairs, �istribute� in three �ifferent regions �ere �is�overe� �uring the perio� 2008�2009. The bree�ing population was estimate� at 30�50 pairs. The stu�y i�enti�e� t�o main habitat types typi�al of the Imperial Eagles in European Turkey – open hilly areas an� lo� mountain areas (up to 450 m a.s.l.) an� lo� relief plain areas (50�150 m a.s.l.). Poplar trees (Populus sp. L) were i�enti�e� as the most preferre� nesting substratum (44%), follo�e� by Oaks (Quercus sp. L) (40%). Bree�ing �ensity �as 1 pair/100 km2 in both habitat types. The shortest �istan�e bet�een t�o bree�ing pairs �as 5.8 km re�or�e� in plain areas in the Thra�e region. -

Separation of Tawny Eagle from Steppe Eagle In

Notes Separation of Tawny Eagle from Steppe Eagle in Israel Tawny Eagle Aquik rapax generally looks smaller and rather puny (and also, when perched, less elongated/horizontal) compared with Steppe Eagle A. nipaknsis. Diagnostically, the North African race A. r. belisarius differs in all plumages from Steppe in being smaller, in having die creamy-white of the uppertail- coverts extending well up onto the upper back (on Steppe, usually restricted to uppertail-coverts, lacking on rump and only indistinct on lower back), in showing a conspicuous sandy wedge on the inner primaries below (generally indistinct or absent on Steppe) and, in juvenile/immature plumages, lacking Steppe's whitish underwing-band; the remiges and rectrices are usually finely barred or almost unbarred compared widi corresponding plumages of Steppe. The general coloration of Tawny's body and underwing-coverts is pale tawny or bufEsh-yellow to pale foxy/rufous (or dark greyish-brown, but this is virtu ally confined to more soumerly populations/races), contrasting highly widi the remiges and rectrices: more or less reminiscent of the underpart pattern of juvenile Imperial Eagle A. heliaca, but unstreaked. The mantle, scapulars and upperwing-coverts are also distincdy tawny-sandy, but with the feathers dark- centred (chiefly on greater coverts, tertials and lower scapulars). In good views, mainly when perched, Tawny normally shows a slighdy shorter gape line, ending level widi the centre of die eye (reaches rear edge on Steppe); die adult's iris is yellowish-brown (dark brown on Steppe). In flight, compared wim Steppe, Tawny has broad and short wings with ample 'hand', and shows a well-protruding head and a relatively short and more square-ended tail; in active flight, it is rather stiff-winged with more rapid wingbeats. -

Nesting Pair Density and Abundance of Ferruginous Hawks (Buteo Regalis) and Golden Eagles (Aquila Chrysaetos) from Aerial Surveys in Wyoming

J. Raptor Res. 49(4):400–412 E 2015 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. NESTING PAIR DENSITY AND ABUNDANCE OF FERRUGINOUS HAWKS (BUTEO REGALIS) AND GOLDEN EAGLES (AQUILA CHRYSAETOS) FROM AERIAL SURVEYS IN WYOMING LUCRETIA E. OLSON1 U.S.D.A., Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula, MT 59801 U.S.A. ROBERT J. OAKLEAF Wyoming Department of Game and Fish, Lander, WY 82520 U.S.A. JOHN R. SQUIRES U.S.D.A., Rocky Mountain Research Station, Missoula, MT 59801 U.S.A. ZACHARY P. WALLACE AND PATRICIA L. KENNEDY Eastern Oregon Agriculture and Natural Resource Program and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Union, OR 97331 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.—Raptors that inhabit sagebrush steppe and grassland ecosystems in the western United States may be threatened by continued loss and modification of their habitat due to energy development, con- version to agriculture, and human encroachment. Actions to protect these species are hampered by a lack of reliable data on such basic information as population size and density. We estimated density and abundance of nesting pairs of Ferruginous Hawks (Buteo regalis) and Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos)in sagebrush steppe and grassland regions of Wyoming, based on aerial line transect surveys of randomly selected townships. In 2010 and 2011, we surveyed 99 townships and located 62 occupied Ferruginous Hawk nests and 36 occupied Golden Eagle nests. We used distance sampling to estimate a nesting pair density of 94.7 km2 per pair (95% CI: 69.9–139.8 km2) for Ferruginous Hawks, and 165.9 km2 per pair (95% CI: 126.8–230.8 km2) for Golden Eagles. -

Repeated Sequence Homogenization Between the Control and Pseudo

Repeated Sequence Homogenization Between the Control and Pseudo-Control Regions in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Subfamily Aquilinae LUIS CADAH´IA1*, WILHELM PINSKER1, JUAN JOSE´ NEGRO2, 3 4 1 MIHAELA PAVLICEV , VICENTE URIOS , AND ELISABETH HARING 1Molecular Systematics, 1st Zoological Department, Museum of Natural History Vienna, Vienna, Austria 2Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Estacio´n Biolo´gica de Don˜ana, Sevilla, Spain 3Centre of Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES), Department of Biology, Faculty for Natural Sciences and Math, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 4Estacio´n Biolo´gica Terra Natura (Fundacio´n Terra Natura—CIBIO), Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain ABSTRACT In birds, the noncoding control region (CR) and its flanking genes are the only parts of the mitochondrial (mt) genome that have been modified by intragenomic rearrangements. In raptors, two noncoding regions are present: the CR has shifted to a new position with respect to the ‘‘ancestral avian gene order,’’ whereas the pseudo-control region (CCR) is located at the original genomic position of the CR. As possible mechanisms for this rearrangement, duplication and transposition have been considered. During characterization of the mt gene order in Bonelli’s eagle Hieraaetus fasciatus, we detected intragenomic sequence similarity between the two regions supporting the duplication hypothesis. We performed intra- and intergenomic sequence comparisons in H. fasciatus and other falconiform species to trace the evolution of the noncoding mtDNA regions in Falconiformes. We identified sections displaying different levels of similarity between the CR and CCR. On the basis of phylogenetic analyses, we outline an evolutionary scenario of the underlying mutation events involving duplication and homogenization processes followed by sporadic deletions. -

Winter Ranging Behaviour of a Greater Spotted Eagle (Aquila

Slovak Raptor Journal 2014, 8(2): 123–128. DOI: 10.2478/srj-2014-0014. © Raptor Protection ofSlovakia (RPS) Winter ranging behaviour of a greater spotted eagle (Aquila clanga) in south- east Spain during four consecutive years Zimné teritoriálne správanie orla hrubozobého (Aquila clanga) v juhovýchodnom Španiel- sku počas štyroch za sebou nasledujúcich rokov Juan M. PÉREZ-GARCÍA, Urmas SELLIS & Ülo VÄLI Abstract: Knowing the winter behaviour is essential for deciding on conservation strategies for threatened migratory species such as the greater spotted eagle (Aquila clanga). Fidelity and inter-annual variation in winter home range of an Estonian greater spotted eagle were studied during the first four years of its life by means of GPS satellite telemetry in south-eastern Spain. Results show the eagle exploited a small area (12.7 km2, 95% kernel) with high inter-annual fidelity during all winter stages. The A. clanga preferred marshes and water bodies and avoided irrigated crops and urban areas. Waterfowl hunting did not show any effect on the spatial pattern of the eagle’s behaviour, although water level management in reservoirs could influence their use by the A. clanga. Our study highlights that the wintering home range may be limited to a small suitable habitat patch where human activities, especially water reservoir management, should be regulated. Abstrakt: Nevyhnutným predpokladom efektívnych ochranárskych opatrení je poznanie zimného správania ohrozeného mi- grujúceho druhu, akým je orol hrubozobý (Aquila clanga). Fidelita a medziročná variabilita charakteristík zimného okrsku jedinca orla hrubozobého pochádzajúceho z Estónska sa sledovala počas prvých štyroch rokov jeho života pomocou GPS-satelit- nej telemetrie v juhovýchodnom Španielsku. -

The Eagle Genus Hieraaetus Is Distinct from Aquila, with Comments on the Name Ayres’ Eagle

William S. Clark 295 Bull. B.O.C. 2012 132(4) The eagle genus Hieraaetus is distinct from Aquila, with comments on the name Ayres’ Eagle by William S. Clark Received 16 April 2012 Consensus has long existed among taxonomists as to the placement of the species of the eagles in the genera Aquila and Hieraaetus, the only exception being Wahlberg’s Eagle, which has been treated either as A. wahlbergi or H. wahlbergi. However, recent comparisons of DNA sequences of these eagles revealed that both genera were polyphyletic (Helbig et al. 2005, Lerner & Mindell 2005, Griffiths et al. 2007, Haring et al. 2007). To ensure monophyly, these authors recommended that some species be moved into and out of both genera and placed Wahlberg’s Eagle definitely in Hieraaetus. On the other hand, Sangster et al. (2005) recommended that Hieraaetus be subsumed into Aquila, for which they cite eight recent phylogenetic studies, only four of them published in peer-reviewed journals (Roulin & Wink 2004, Bunce et al. 2005, Helbig et al. 2005, Lerner & Mindell 2005); all of which, nevertheless, retained Hieraaetus. Thus, none of the four peer-reviewed journal articles cited by Sangster et al. (2005) to justify placing Hieraaetus into Aquila actually recommended this. Further, Sangster et al. (2005) proposed only that Booted Eagle (pennatus) be included in Aquila, because their recommendations only considered European birds. The generic treatment of Sangster et al. (2005) was followed without comment by Gjershaug et al. (2009) in describing Weiske’s or Pygmy Eagle (weiskei) as a species separate from Little Eagle H. -

The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Gyps Coprotheres (Aves, Accipitridae, Accipitriformes): Phylogenetic Analysis of Mitogenome Among Raptors

The complete mitochondrial genome of Gyps coprotheres (Aves, Accipitridae, Accipitriformes): phylogenetic analysis of mitogenome among raptors Emmanuel Oluwasegun Adawaren1, Morne Du Plessis2, Essa Suleman3,6, Duodane Kindler3, Almero O. Oosthuizen2, Lillian Mukandiwa4 and Vinny Naidoo5 1 Department of Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 2 Bioinformatics and Comparative Genomics, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 3 Molecular Diagnostics, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 4 Department of Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa 5 Paraclinical Science/Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa 6 Current affiliation: Bioinformatics and Comparative Genomics, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa ABSTRACT Three species of Old World vultures on the Asian peninsula are slowly recovering from the lethal consequences of diclofenac. At present the reason for species sensitivity to diclofenac is unknown. Furthermore, it has since been demonstrated that other Old World vultures like the Cape (Gyps coprotheres; CGV) and griffon (G. fulvus) vultures are also susceptible to diclofenac toxicity. Oddly, the New World Turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) and pied crow (Corvus albus) are not susceptible to diclofenac toxicity. As a result of the latter, we postulate an evolutionary link to toxicity. As a first step in understanding the susceptibility to diclofenac toxicity, we use the CGV as a model species for phylogenetic evaluations, by comparing the relatedness of various raptor Submitted 29 November 2019 species known to be susceptible, non-susceptible and suspected by their relationship Accepted 3 September 2020 to the Cape vulture mitogenome. -

Golden Eagle (Aquila Chrysaetos)

Birds Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) Status State: Fully Protected species Federal: Protected under the Bald Eagle and Golden Eagle Protection Act Population Trend Gerald and Buff Corsi © California Academy of Sciences Global: Apparently stable in most areas of western U.S.; unknown elsewhere State: Declining in southern California; common and presumably stable elsewhere in California Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization Extensive long-term studies have been conducted on the distribution, demographics, and general biology of golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the vicinity of the ECCC HCP/NCCP inventory area as part of investigations on the impact of wind turbine operation on this species (see Hunt et al. 1998). These studies provide detailed information on the distribution and habitat-use patterns of resident and non-resident golden eagles, population structure, reproductive rates, survival rates, and population equilibrium dynamics. A moderate amount of additional literature is available for the golden eagle outside the inventory area because it is a highly visible, fully protected bird of prey and top avian predator within its range. Most of the literature pertains to general natural history, behavior, distribution, and population changes in the past 30 to 40 years. Some information is available on demographics and population trends. Limited species-specific management information is available. Range The golden eagle is Holarctic in distribution. In North America, it breeds from northern and western Alaska east to the Northwest Territories, Canada, and south to southern Alaska, Baja California, the highlands of northern Mexico, west- central Texas, western portions of Oklahoma, Nebraska, and the Dakotas, and irregularly in eastern North America. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

Cranial Osteology of Tawny and Steppe Eagles Aquila Rapax and A

26 2, S. L. Okw 26+ Ad* B.O.C. 1994114(4) Cranial osteology of Tawny and Steppe Eagles j4gm/a n#a% and ^4. wpo/gwff Although the Tawny Eagle .dgwia ra/wz% and Steppe Eagle ^4. mpa/wuw are now often treated as subspecies of a single species (^4. ropa%), Clark (1992) recently presented a convincing analysis of plumage, external morphology, distribution and habits, from which he concluded that these are two very distinct species, as they were regarded by most writers in the Grat half of this century and before. One of the significant differences in the two species noted by Clark is the greater width of the gape in A. nipalensis. With this in mind, I thought it would be of interest to investigate to what degree the underlying skull structure would reflect this difference and might otherwise support Clark's conclusion. Several skeletons of ^4. ropo* were immediately at hand but locating one of ^4. wpa/eww proved something of a task because the world inventory of avian skeletons (Wood & Schnell 1986) includes both species under ^4. ra^wzx. This provides a good example of the manner in which information is only lost by unsubstantiated lumping of species-level taxa. After considerable correspondence, I was able to locate and examine a single skull and mandible of X. n^»afew#j (UMMZ 215418), from an individual taken in Turkmenistan, on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, which was compared with 5 individuals of ^4. rapax. The skull in ^4. mipabww is not only decidedly larger but also more elongate, so that the interorbital bridge is proportionately narrower than in A. -

Lead Poisoning of Steller's Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus Pelagicus)

LEAD POISONING OF STELLER’S SEA‐EAGLE (HALIAEETUS PELAGICUS) AND WHITE‐TAILED EAGLE (HALIAEETUS ALBICILLA) CAUSED BY THE INGESTION OF LEAD BULLETS AND SLUGS, IN HOKKAIDO, JAPAN KEISUKE SAITO Institute for Raptor Biomedicine Japan, Kushiro Shitsugen Wildlife Center, 2-2101 Hokuto Kushiro Hokkaido Japan, Zip 084-0922. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—The Steller’s Sea-Eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) and the White-tailed Eagle (H.albicilla) are among the largest eagles. The total population of the Steller’s Sea-Eagle is estimated at 5,000 to 6,000 in- dividuals, and these eagles winter in large numbers in northern Japan, on the island of Hokkaido. Lead poi- soning of Steller’s Sea-Eagles in Japan was first confirmed in 1996. By 2007, 129 Steller’s and White- tailed Eagles had been diagnosed as lead poisoning fatalities. High lead values up to 89 ppm (wet-weight) from livers of eagles available for testing indicate that they died from lead poisoning. Necropsies and ra- diographs also revealed pieces of lead from rifle bullets and from shotgun slugs to be present in the diges- tive tracts of poisoned eagles, providing evidence that a source of lead was spent ammunition from lead- contaminated Sika Deer carcasses. Tradition and law in Japan allow hunters to remove the desirable meat from animals and abandon the rest of the carcass in the field. Deer carcasses have now become a major food source for wintering eagles. Reacting to the eagle poisoning issue, Hokkaido authorities have regulated the use of lead rifle bullets since 2000. The Ministry of the Environment mandated use of non-toxic rifle bullets or shotgun slugs beginning the winter of 2001.