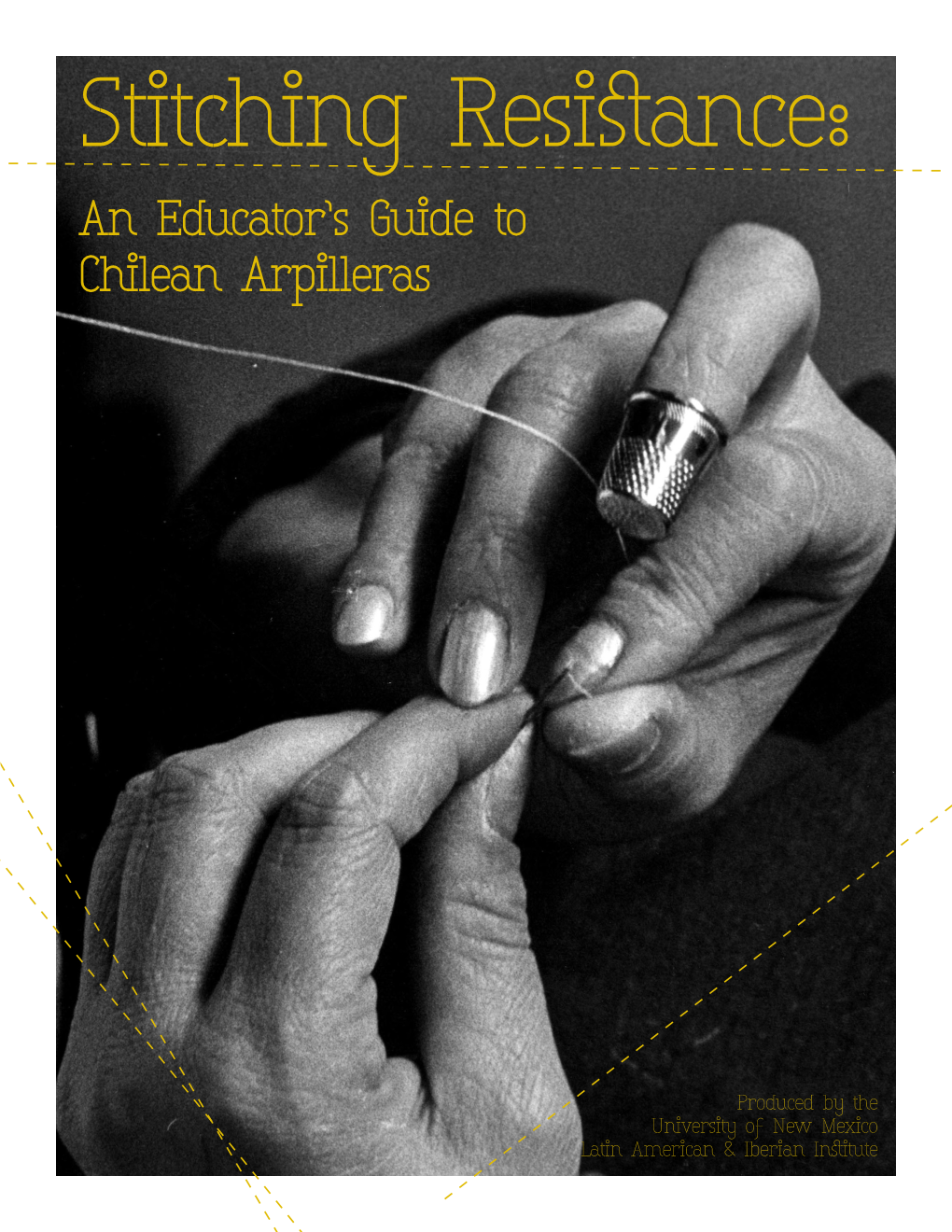

Stitching Resistance: an Educator’S Guide to Chilean Arpilleras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queremos Democracia / We Want Democracy Chilean Arpillera, Vicaría De La Solidaridad, 1988 Photo Martin Melaugh

Queremos Democracia / We want democracy Chilean arpillera, Vicaría de la Solidaridad, 1988 Photo Martin Melaugh This arpillera, from a Chilean church community workshop, depicts the However, Agosín (2008) maintains that women were not given due “people’s power” in insisting on their rights to a peaceful, nonviolent recognition in the new democracy: “…democracy has not acknowledged society. The bright colours of the houses and the women’s clothes the significance of the arpilleristas and other women’s groups…who had convey hope. However, the presence of the police car reminds us that a fundamental role to play in the return of democracy.” overcoming the barriers to poverty and peace are not easy. In this difficult context they carry a banner that reads “democracy” hoping that if this is Courtesy of Seán Carroll, USA achieved, things will change. They want to be part of the process. 24 The next four arpilleras, recently brought back from Chile, are an account by a Chilean arpillerista of recent events in the country. Direct confrontation between the indigenous Mapuche people, who consider themselves a separate people, and the Chilean State, who consider them Chileans, is the overarching theme depicted. Hermanos Mapuche en huelga de hambre / Mapuche people on hunger strike Chilean arpillera, Aurora Ortiz, 2011 Photo Martin Melaugh This poignant arpillera is the testimony of a recent historical (2010) The Mapuche flag is placed in a prominent place to reinforce their episode experienced by the Mapuche people, who have suffered identity. The artist has added her support by embroidering a banner colonisation for over 500 years. -

Arpilleras: Evolution and Revolution

Arpilleras: Evolution and Revolution Public lecture – Friends of Te Papa, Main theatre, Te Papa Tongarewa, Monday 2 September , 2013 Roberta Bacic Curator, www.cain.ulst.ac.uk/quilts August 2013 Introduction Arpilleras, from their humble origins in Chile, have traversed the globe, prompting much debate, resistance and action in their wake. In this brief address I will focus on the origins of arpilleras and how they evolved, the revolutionary nature of arpilleras and their universal journey. The origins and evolution of arpilleras What are arpilleras? Arpilleras (pronounced "ar-pee-air-ahs") are three-dimensional appliquéd tapestries of Latin America that originated in Chile. The backing fabric of strong hessian, “arpillera” in Spanish became the name for these particular type of sewed pictures which came to mean the cloth of resistance. As empty potato or flour bags, materials at hand in any household, were also used for the backing, the typical arpillera size is a quarter or a sixth of a bag. At a later stage, the sewing of cloth figures and other small memorabilia onto these “cuadros” (pictures) evolved, giving them a special personalized quality and a three dimensional effect. We believe that contemporary arpilleras originated in Isla Negra on the Chilean coastline. Around 1966 Leonor Sobrino, a long standing summer visitor to the area, prompted local women to use embroidery to depict scenes of their everyday lives. The group of women became Las Bordadoras de Isla Negra (the Embroiders of Isla Negra) and, mainly in the long 1 winter months, they embroidered bucolic scenes of their everyday rural lives. -

Palmerston North City Library Massey University School of Language Studies Latin American Society

Palmerston North City Library Massey University School of Language Studies Latin American Society Present the 2010 Latin American Film Festival in Palmerston North 12-23 October – 7pm City Library’s Sound & Vision Zone All films in Spanish with English subtitles Gold Coin Donation With Support from and Friends of the Library TUESDAY 12 OCTOBER – 7 pm El secreto de sus ojos / The Secret in Their Eyes Argentina – Directed by Juan José Campanella Running time: 129 min The Secret in Their Eyes Reviewed by Matthew Turner – The ViewLondon Review Beautifully made and superbly written, this is an emotionally absorbing thriller with a terrific central performance from Ricardo Darin. What's it all about? The winner of the 2010 Oscar for best foreign film, The Secret in Their Eyes is directed by Juan Jose Campanella and stars Ricardo Darin (Nine Queens) as Benjamin Esposito, a recently retired criminal court investigator, whose efforts to write a novel are frustrated when he finds himself unable to shake the memories of a 25-year-old murder case. After visiting his ex-superior Irene (Soledad Villamil), who's now a high court judge, Benjamin decides to reinvestigate the case and we flash back to his first view of the crime scene, where a beautiful young woman was raped and murdered. As Benjamin attempts to recall the details of the case, the various events unfold, from the questioning of the victim's troubled husband (Pablo Rago) to the discovery and arrest of a probable suspect (Javier Godino), only for the authorities to subsequently let him go for nefarious purposes of their own. -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Transforming Threads of Resistance: Political Arpilleras & Textiles by Women from Chile and Around the World

TRANSFORMING THREADS OF RESISTANCE: POLITICAL ARPILLERAS & TEXTILES BY WOMEN FROM CHILE AND AROUND THE WORLD The Art of Conflict Transformation Event Series Presents Transforming threads of resistance: political arpilleras & textiles by women from Chile and around the world Foreword Since 2008 the interdisciplinary Art of Conflict Transformation Event Series has served as a platform, bringing to the University of Massachusetts Amherst scholars, artists, and conflict resolvers to explore the geography of conflict; the spaces in and on which conflict has been imprinted and expressed; and the terrains of resistance, resilience, and transformation. In 2012 we are proud to host events focusing on women’s acts of resistance to state violence in conflict zones throughout the world through their creation of arpilleras and other political textiles. The exhibition on display at the Student Union Art Gallery serves as the centerpiece of six weeks of activities interrogating women’s critical engagement with state oppression and their crafting of visual narratives that have defied silencing. The Art of Conflict Transformation Art Gallery of the National Center for Technology and Dispute Resolution also hosts this exhibition online at http://blogs.umass.edu/conflictart. The Art of Conflict Transformation Event Series is indebted to Dr. John Mullin, Dean of the Graduate School, whose visionary and steadfast support has been instrumental to its success. Outstanding administrative support has been provided for the 2012 activities by Michelle Goncalves from the Legal Studies and Political Science Programs. A very special thanks goes to internationally renowned curator Roberta Bacic, whose arpilleras exhibitions have been shown in museums and at universities throughout the globe. -

Affect, Spectacle, and Horror in Pablo Larraín's Post Mortem

chapter 13 Affect, Spectacle, and Horror in Pablo Larraín’s Post Mortem (2010) Rosa Tapia Abstract Post Mortem by Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín challenges traditional cinematic con- ventions of affect and spectacle through a narrative of spaces and bodies that is neither realist, comedic, nor melodramatic. This chapter draws upon affect theories that study the spectacle of cinematic spaces and political bodies in Latin American film. The pro- tagonist of Larraín’s film is an inconsequential morgue clerk who transcribed the details of Salvador Allende’s autopsy after the president’s death in the 11th September 1973 coup d’état. Post Mortem intentionally abstains from an explicit political commentary or sen- timental release. The plot and cinematic technique combine to paint an uncomfortably naked image of evil, without guilt-ridden or heroic characters. The systematic disloca- tion, defamiliarization, and desecration of spaces sacralized by the collective memory allows Larraín’s film to trespass the affective boundaries of political melodrama. Spaces that should have been familiar appear eerily distant and strange, morphing into dystop- ic versions of themselves as hospitals become morgues and body dumpsters, city streets turn into empty battlefields, and homes are now targets, prisons, or tombs. Chile has produced relatively few films about its seventeen- year dictatorship (1973– 1990). Unlike the many blockbusters that filmmakers from Spain and Argentina have dedicated to their own civil conflicts and dictatorships, most Chilean films on the subject have had limited viewership, with the notable exceptions of Andrés Wood’s Machuca (2004) and Pablo Larraín’s No (2012).1 Unsurprisingly, a comparison of audience size shows that more theatergoers 1 Barraza Toledo states that from 2003 to 2013 there were only a handful of Chilean films that depicted or focused on the Pinochet era. -

Chilean Arpilleras: Writing a Visual Culture R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2018 Chilean Arpilleras: Writing a Visual Culture R. Darden Bradshaw University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Bradshaw, R. Darden, "Chilean Arpilleras: Writing a Visual Culture" (2018). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1069. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1069 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings 2018 Presented at Vancouver, BC, Canada; September 19 – 23, 2018 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/ Copyright © by the author(s). doi 10.32873/unl.dc.tsasp.0023 Chilean Arpilleras: Writing a Visual Culture R. Darden Bradshaw [email protected] Demonstration outside of a church, 00001; M. Dieter collection ©Museum of Memory and Human Rights, Santiago, Chile Arpilleras, historically created in the home and sewn by hand, are constructions of pictorial narratives in which bits of discarded cloth are appliqued onto a burlap backing. The art form has been historically practiced in Chile for some time but arose to global prominence during a period of intense political oppression; these works of art, created in response to the atrocities committed by the Pinochet regime from 1973 to 1990 have served, and continue to serve, as seditious and reconstructive forms of visual culture. -

History in Chilean Fiction Films: Strategies for an Audiovisual Common Sense Production*

160 Comunicación y Medios N°39 (2019) C. Salinas / H. Stange / E. Santa Cruz / C. Kulhman History in Chilean Fiction Films: Strategies for an Audiovisual Common Sense Production* La historia en el cine de ficción chileno: estrategias de producción de un sentido común audiovisual Claudio Salinas Hans Stange Universidad de Chile, Chile Universidad de Chile, Chile [email protected] [email protected] Eduardo Santa Cruz Carolina Kulhman Universidad de Chile, Chile Universidad de Chile, Chile [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Resumen The text reports the conclusions of a study that El texto da cuenta de los resultados de una inves- aims to identify the characteristics of the histori- tigación, cuyo propósito fue establecer las carac- cal discourses produced by Chilean fiction cinema, terísticas de los discursos históricos vehiculizados assuming that Chilean cinema has not properly por el cine chileno de ficción, bajo la premisa de developed “historical” genres. Therefore, how does que no se han desarrollado propiamente géne- Chilean cinema represent history? We argue that ros que podamos llamar “históricos”. ¿Cómo Chilean fiction films representations produce a representa entonces el cine chileno la historia? historical verisimilar, that is, an aesthetic-narrative Nuestra hipótesis es que las representaciones device that resorts to present-day social imaginar- cinematográficas producen un verosímil histórico, ies, with which an ‘effect of reality’ in representa- es decir, un mecanismo estético-narrativo que re- tion is achieved. On the grounds that this device curre a imaginarios sociales del presente y con los would not be primarily historical discourses, but que se consigue un efecto de realidad en la rep- an ‘audiovisual common sense’ that gives famil- resentación. -

Identidad Y Memoria De Los Presos Políticos De Isla Dawson (1970-1990)”

Universidad de Magallanes Facultad de Educación y Ciencias Sociales Departamento de Educación y Humanidades “Identidad y Memoria de los Presos Políticos de Isla Dawson (1970-1990)” Tesis para optar al título profesional de Profesor de Historia y Cs. Sociales Alumnos: Juan Andrés Aliaga Bustamante Luis Jonathan Toledo Villalón Director de Seminario: Sr. Fernando Bahamonde Avendaño Punta Arenas, Diciembre 2014 Dedicatoria. En la etapa culmine de este ciclo, dedicar este logro especialmente a mi familia, a mi mamá por todo el apoyo, esfuerzo y cariño brindado a lo largo de estos años, te amo chechita. A mis abuelos, papi Alejo y mami Nena por toda la atención y afecto que recibí de ustedes desde que era niño, gracias viejitos. A mis tíos Jaime, Gastón, Gilda, Silvia y mi primita Natalia, por estar aparecer alegrándome la vida a lo largo de los años, los quiero mucho. A mi hermanita chola por aparecer en mi vida y demostrarme que tener una hermana es algo hermoso. Por último a Laura, mi compañera en estos últimos años, gracias por la paciencia y la compañía en todo momento, te amo mi fea. Juan Andrés Aliaga Bustamante. En este termino de etapa, quiero agradecer el total apoyo de mis padres, mis hermanos y a toda mi familia, asi también el motivo del esfuerzo entregado a mi hija Anaelle. Luis Jonathan Toledo Villalón. 2 Agradecimientos A nuestro profesor guía de tesis por la disposición y la buena onda. Gracias profe Bahamonde. A don Baldovino por la ayuda prestada para llevar a cabo este trabajo. A todos quienes prestaron testimonios y que hicieron posible esta investigación 3 ÍNDICE DEDICATORIA. -

Reviewing the Present in Pablo Larraín's Historical Cinema*

Reviewing the Present in Pablo Larraín’s Historical Cinema* Vania Barraza Toledo University of Memphis, USA Abstract: Pablo Larraín’s film trilogy about the Chilean dictatorshipexplores the contra- dictions of memory haunting contemporary society, establishing a dialogue between a present and a dreadful past. The protagonists of Tony Manero (2008) and Post Mortem (2010) symbolize traumatized subjects embodying a dual temporality, becoming the living dead in a lifeless society. They belong to the domain of between two deaths, returning to collect an unpaid symbolic debt. Both characters bring back the memory of an inconve- nient past to Chilean society reporting a haunting history. Hence, Larraín’s movies review the political transition as a tension between oblivion and the incomplete postdictatorial task of mourning. This essay analyzes the figure of the undead epitomizing the debt of Chilean society to its history. Keywords: Pablo Larraín; Postdictatorship; Trauma, Memory; Film; Chile; 20th-21st Century. Resumen: La trilogía cinematográfica de Pablo Larraín sobre la dictadura chilenarefiere a las contradicciones de una memoria en acecho sobre una sociedad contemporánea, para establecer un diálogo entre un presente y un pasado ominoso. Los protagonistas de Tony Manero (2008) y Post Mortem (2010) simbolizan sujetos traumatizados que encarnan una temporalidad dual, transformándose en muertos vivos de una sociedad sin vida. Pertenecen al dominio de entre dos muertes, regresando para cobrar una deuda simbólica impaga. Ambos personajes traen el recuerdo de un pasado incómodo para la sociedad chilena, al reportar una historia que se manifiesta de manera acechante. Por lo tanto, los filmes de Larraín revisan la transición política como una tensión entre el olvido y el trabajo de duelo incompleto de la posdictatura. -

Panorama Del Audiovisual Chileno

Obra realizada con aporte de la Dirección de Artes y Cultura de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile PANORAMA DEL AUDIOVISUAL CHILENO Valerio Fuenzalida + Pablo Julio (editores)/ Cristián Amaya/Alejandro Caloguerea/Soledad Gutiérrez/Alexis Ibarra/David Inostroza/Carola Leiva/Carol Neumann/Tamara Oliveri/Ignacio Polidura/Verónica Silva/Carolina Vergara Obra realizada con aporte de la Dirección de Artes y Cultura de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile PANORAMA DEL AUDIOVISUAL CHILENO Valerio Fuenzalida + Pablo Julio (editores)/ Cristián Amaya/Alejandro Caloguerea/Soledad Gutiérrez/Alexis Ibarra/David Inostroza/Carola Leiva/Carol Neumann/Tamara Oliveri/Ignacio Polidura/Verónica Silva/Carolina Vergara Editores Valerio Fuenzalida. Profesor e Investigador en la Facultad de Comunicaciones de la Universidad Católica, especializado en investigación de audiencias, TV pública, y TV infantil. Pablo Julio. Ingeniero Civil de Industrias y Magíster en Administración, académico de la Facultad de Comunicaciones de la Universidad Católica. Colaboradores Cristián Amaya. Periodista. Magíster en Comunicación, mención Dirección y Edición Periodística de la Universidad Católica. Alejandro Caloguerea. Ingeniero Comercial. Gerente de CAEM A.G. Soledad Gutiérrez. Periodista, especializada en audiovisual. Alexis Ibarra. Periodista, especializado en tecnología. David Inostroza. Periodista. Maestría© en Economía. Carola Leiva. Periodista. Máster en Dirección de Empresa Audiovisual, ex Secretaria Ejecutiva del Consejo del Arte y la Industria Audiovisual. Carol Neumann. Estudiante de Periodismo de la Facultad de Comunicaciones de la Universidad Católica. Tamara Oliveri. Directora Audiovisual de la Universidad Católica. Productora de Televisión. Ignacio Polidura. Sociólogo, especializado en audiovisual. Verónica Silva. Psicóloga, especializada en audiovisual. Carolina Vergara. Periodista. Máster en Dirección de la Empresa Audiovisual. Diseño. Bercz Dirección creativa. Dany Berczeller + Consuelo Saavedra Diseño editorial. -

Pablo Larraín's Post Mortem

Films about the Dictatorship • La frontera (Ricardo Larraín, 1991) • Amnesia (Gonzalo Justiniano, 1994) • Machuca (Andres Wood, 2004) • Dawson, Isla 10 (Miguel Littín, 2009) • Nostalgia de la luz (Patricio Guzmán, 2013) Julio comienza en Julio (Silvio Caiozzi, 1979) 1990s onwards • 1990 – Ley de donaciones culturales (amplified in 2001 and 2013) • Year 2000: 11 Chilean films released • 1999-2002 – Private-State funding ratio of 2:1 • 2004: 274 cinemas in the country; 158 in Santiago • 2006: Ley de Fomento Audiovisual • 2006: Consejo del Arte y la Industria Audiovisual Branding Chilean Cinema • ‘sí estamos fallando en algo, en que estamos usando recursos de todos los chilenos para hacer películas que después ven 1.000 personas. Hay que hacer una película que se comunique con el público’, Gregorio González. http://www.latamcinema.com/sanfic- 8-las-divergencias-del-mercado-cinematografico-chileno/ • valora el patrimonio audiovisual, por lo que le permite actuar en el conjunto de la cadena de valor de la actividad, desde la creación, la producción, la distribución y la exhibición, la promoción internacional y el apoyo a la actividad patrimonial y cultural, por medio de festivales, como también en el desarrollo del audiovisual en regiones. (Florencia Rosenfeld de la Torre, 2006, p. 27). • no existe todavía una imagen que identifique al cine chileno y que logre que el público se acerque con confianza a ver las películas nacionales. (Ibid, p. 8) Pablo Larraín's Trilogy • Tony Manero (Pablo Larraín, 2008) • Post-mortem (Pablo Larraín, 2010) •