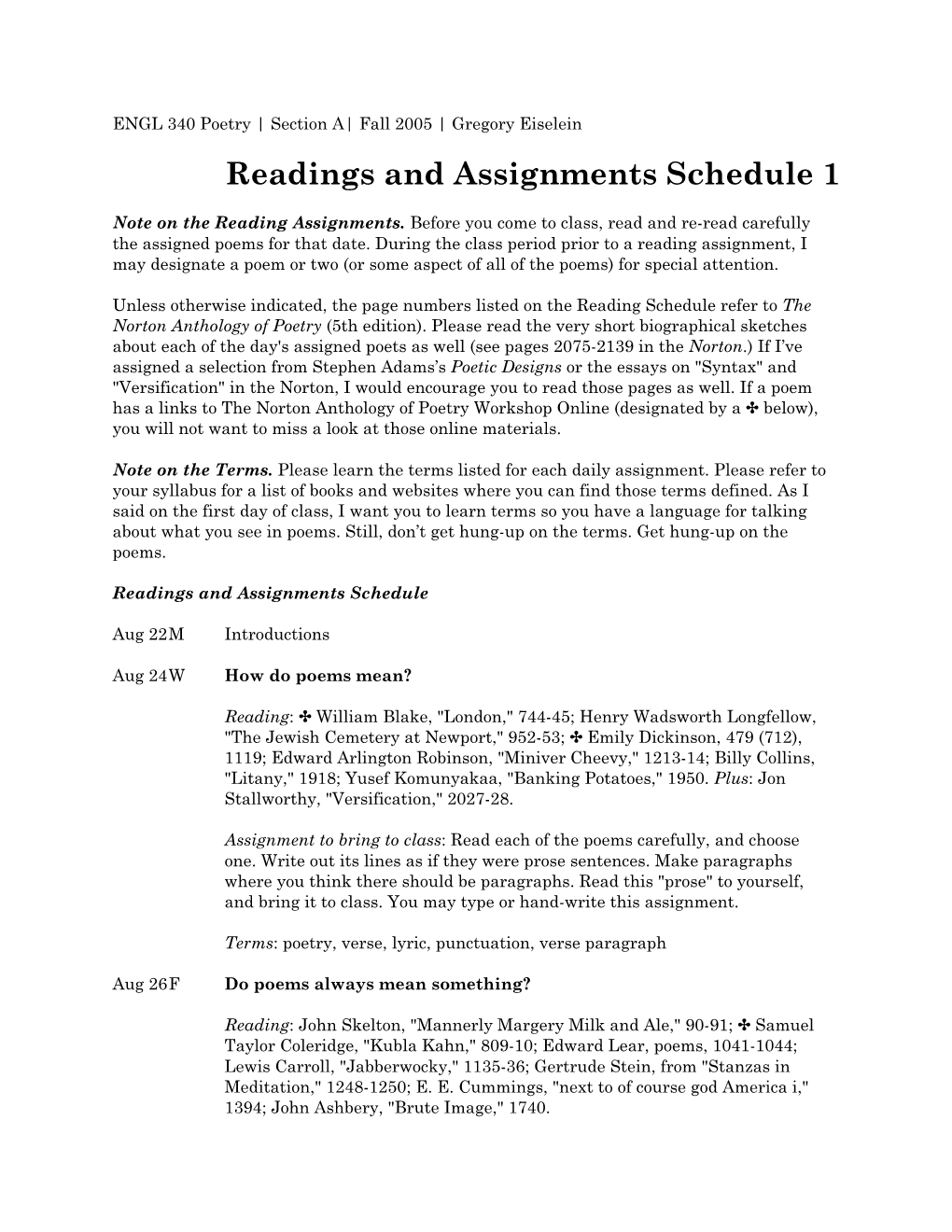

Readings and Assignments Schedule 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emigrants 1811

Charlotte Smith, The Emigrants Do a close reading of the preface to The Emigrants (1793) in comparison with the various prefaces to Elegiac Sonnets (especially the 6th edition) and her gothic novel of the French Revolution, Desmond (1792). How does Smith negotiate claims of authority in the midst of gendered deference? How does her authorial self-presentation differ in these different contexts? How does it remain the same? Does form or history seem to matter more to her construction of herself as (political) author? Outline “The Emigrants” stanza by stanza. What happens in each stanza? What larger structures or movements can you discern? What differences do you notice between the first book and the second? In particular, do a close reading of the first two stanzas of the poem: How would you paraphrase the opening verse paragraph? What’s unusual about this as a poetic beginning? What kinds of diction rule the opening lines? Do you hear an allusion to any earlier works in the ending of the stanza? What do you make of the (excessive?) alliteration in lines 15 and 16: what does that do for the poem? Paraphrase the second stanza. What’s the movement of the second verse paragraph? If poetry is shaped through repetition and variation, what is repeated and what varied in these lines? How do parenthetical remarks function? (Are they the same here as in the first stanza?) What allusions appear? When does the “I” appear in the poem, not just in the beginning, but throughout? How would you summarize its function in each appearance? “The Emigrants” was criticized for “egotism” both as a moral limitation and as a formal confusion. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A HISTORY OF LAUREATE POETICS, 1399-1616 Christine Maffuccio, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Theresa Coletti Department of English My dissertation analyzes lowbrow literary forms, tropes, and modes in the writings of three would-be laureates, writers who otherwise sought to align themselves with cultural and political authorities and who themselves aspired to national prominence: Thomas Hoccleve (c. 1367-1426), John Skelton (c. 1460-1529), and Ben Jonson (1572-1637). In so doing, my project proposes a new approach to early English laureateship. Previous studies assume that aspiration English writers fashioned their new mantles exclusively from high learning, refined verse, and the moral virtues of elite poetry. In the writings and self-fashionings that I analyze, however, these would-be laureates employed literary low culture to insert themselves into a prestigious, international lineage; they did so even while creating personas that were uniquely English. Previous studies have also neglected the development of early laureateship and nationalist poetics across the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. Examining the ways that cultural cachet—once the sole property of the elite—became accessible to popular audiences, my project accounts for and depends on a long view. My first two chapters analyze writers whose idiosyncrasies have afforded them a marginal position in literary histories. In Chapter 1, I argue that Hoccleve channels Chaucer’s Host, Harry Bailly, in the Male Regle and the Series. Like Harry, Hoccleve draws upon quotidian London experiences to create a uniquely English writerly voice worthy of laureate status. In Chapter 2, I argue that Skelton enshrine the poet’s own fleeting historical experience in the Garlande of Laurell and Phyllyp Sparowe by employing contrasting prosodies to juxtapose the rhythms of tradition with his own demotic meter. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading Elon Lang Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) January 2010 Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading Elon Lang Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lang, Elon, "Thomas Hoccleve and the Poetics of Reading" (2010). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 192. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/192 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English and American Literature Dissertation Examination Committee: David Lawton, Chair Antony Hasler William Layher Joseph Loewenstein William McKelvy Jessica Rosenfeld THOMAS HOCCLEVE AND THE POETICS OF READING by Elon Meir Lang A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 Saint Louis, Missouri copyright by Elon Meir Lang August 2010 Acknowledgements In writing this dissertation on Thomas Hoccleve, who so often describes his reliance on the support of patrons in his poetry, I have become very conscious of my own indebtedness to numerous institutions and individuals for their generous patronage. I am grateful to the Washington University Department of English and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences for their academic and financial support during my graduate student career. I feel fortunate to have been part of a department and school that have enabled me to do research at domestic and international archives through both independent funding initiatives and an association with the Newberry Library Consortium. -

Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Diacritics: A Corpus Based Study by Claire Moore-Cantwell This is my difficulty, what marks to use and when to use them: they are so much needed, and yet so objectionable.1 ~Hopkins 1. Introduction In a letter to his friend Robert Bridges, Hopkins once wrote: “... my apparent licences are counterbalanced, and more, by my strictness. In fact all English verse, except Milton’s, almost, offends me as ‘licentious’. Remember this.”2 The typical view held by modern critics can be seen in James Wimsatt’s 2006 volume, as he begins his discussion of sprung rhythm by saying, “For Hopkins the chief advantage of sprung rhythm lies in its bringing verse rhythms closer to natural speech rhythms than traditional verse systems usually allow.”3 In a later chapter, he also states that “[Hopkins’] stress indicators mark ‘actual stress’ which is both metrical and sense stress, part of linguistic meaning broadly understood to include feeling.” In his 1989 article, Sprung Rhythm, Kiparsky asks the question “Wherein lies [sprung rhythm’s] unique strictness?” In answer to this question, he proposes a system of syllable quantity coupled with a set of metrical rules by which, he claims, all of Hopkins’ verse is metrical, but other conceivable lines are not. This paper is an outgrowth of a larger project (Hayes & Moore-Cantwell in progress) in which Kiparsky’s claims are being analyzed in greater detail. In particular, we believe that Kiparsky’s system overgenerates, allowing too many different possible scansions for each line for it to be entirely falsifiable. The goal of the project is to tighten Kiparsky’s system by taking into account the gradience that can be found in metrical well-formedness, so that while many different scansion of a line may be 1 Letter to Bridges dated 1 April 1885. -

John Skelton (1460?–1529)

Hunter: Renaissance Literature 9781405150477_4_001 Page Proof page 17 16.1.2009 4:27pm John Skelton (1460?–1529) Although there is little reliable information and vulgar erotic verse (‘‘The Tunning of about Skelton’s early life, he appears to have Elynour Rummyng’’). During his rectorship he studied at both Cambridge and Oxford, where also wrote two comic Latin epitaphs on mem- he was awarded the title of ‘‘laureate’’ (an bers of his congregation (‘‘Epitaph for Adam advanced degree in rhetoric) in 1488; he later Udersall’’ and ‘‘A Devout Trental for Old John received the same honor from the universities Clarke’’) which anticipate the satirical vein of of Cambridge and Louvain. Some time in the his later poetry. He also wrote Latin verse and 1490s, he went up to London and the court, made some translations from Latin. The tone where he wrote some occasional poems and and themes of his poems vary wildly within as dramatic entertainments. In 1498, Skelton well as between them, and he excels at using took holy orders and soon after became the commonplace situations as comic vehicles for tutor of Prince Henry (later King Henry learned disputes or reflections. A good example VIII). When Erasmus visited England in is ‘‘Ware the Hawk,’’ a poem about a neighbor- 1499, he described Skelton as unum Britanni- ing curate who has been hunting with his hawk carum litterarum lumen ac decus (‘‘the singular in Skelton’s church at Diss. The bird’s fouling of light and glory of British letters’’); while he the altar, chalice, and host becomes the occa- had his detractors as well, this shows that sion for a poetic sermon (carefully divided into Skelton was an established poet and scholar named sections) and a table of conclusions for and he has always been considered the most the erring hawk-owner to follow. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

Poetry: Why? Even Though a Poem May Be Short, Most of the Time You Can’T Read It Fast

2.1. Poetry: why? Even though a poem may be short, most of the time you can’t read it fast. It’s like molasses. Or ketchup. With poetry, there are so many things to take into consideration. There is the aspect of how it sounds, of what it means, and often of how it looks. In some circles, there is a certain aversion to poetry. Some consider it outdated, too difficult, or not worth the time. They ask: Why does it take so long to read something so short? Well, yes, it is if you are used to Twitter, or not used to poetry. Think about the connections poetry has to music. Couldn’t you consider some of your favorite lyrics poetry? 2Pac, for example, wrote a book of poetry called The Rose that Grew from Concrete. At many points in history across many cultures, poetry was considered the highest form of expression. Why do people write poetry? Because they want to and because they can… (taking the idea from Federico García Lorca en his poem “Lucía Martínez”: “porquequiero, y porquepuedo”) You ask yourself: Why do I need to read poetry? Because you are going to take the CLEP exam. Once you move beyond that, it will be easier. Some reasons why we write/read poetry: • To become aware • To see things in a different way • To put together a mental jigsaw puzzle • To move the senses • To provoke emotions • To find order 2.2. Poetry: how? If you are not familiar with poetry, you should definitely practice reading some before you take the exam. -

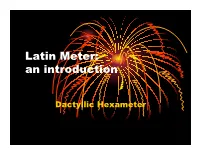

Dactylic Hexameter Is Properly Scanned When Divided Into Six Feet, with Each Foot Labelled a Dactyl Or a Spondee

Latin Meter: an introduction Dactyllic Hexameter English Poetry: Poe’s “The Raven”—Trochaic Octameter / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x Once up- on a mid- night drear- y, while I pon- dered weak and wear- y / x / x x / x / x x / x / x / x / O- ver man- y a quaint and cur- i- ous vol- ume of for- got- ten lore, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / x While I nod- ded, near- ly nap- ping, sud- den- ly there came a tap- ping, / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / As of some- one gent- ly rap- ping, rap- ping at my cham- ber door. / x / x / x / x / x / x / x / “’Tis some vis- i- tor,” I mut- tered, “tap- ping at my cham- ber door; / x / x / x / On- ly this, and noth- ing more.” Scansion n Scansion: from the Latin scandere, “to move upward by steps.” Scansion is the science of scanning, of dividing a line of poetry into its constituent parts. n To scan a line of poetry is to follow the rules of scansion by dividing the line into the appropriate number of feet, and indicating the quantity of the syllables within each foot. n A line of dactylic hexameter is properly scanned when divided into six feet, with each foot labelled a dactyl or a spondee. Metrical Symbols: long: – short: u syllaba anceps: u (may be long or short) Basic Feet: dactyl: – u u spondee: – – Dactylic Hexameter: Each line has six feet, of which the first five may be either dactyls or spondees, though the fifth is nearly always a dactyl (– u u), and the sixth must be either a spondee (– –) or a trochee (– u), but we will treat it as a spondee. -

The Phonology of Classical Arabic Meter Chris Golston & Tomas Riad 1

The Phonology of Classical Arabic Meter Chris Golston & Tomas Riad 1. Introduction* Traditional analysis of classical Arabic meter is based on the theory of al-Xalı#l (†c.791 A.D.), the famous lexicographist, grammarian and prosodist. His elaborate circle system remains directly influential in theories of metrics to this day, including the generative analyses of Halle (1966), Maling (1973) and Prince (1989). We argue against this tradition, showing that it hides a number of important generalizations about Arabic meter and violates a number of fundamental principles that regulate metrical structure in meter and in natural language. In its place we propose a new analysis of Arabic meter which draws directly on the iambic nature of the language and is responsible to the metrical data in a way that has not been attempted before. We call our approach Prosodic Metrics and ground it firmly in a restrictive theory of foot typology (Kager 1993a) and constraint satisfaction (Prince & Smolensky 1993). The major points of our analysis of Arabic meter are as follows: 1. Metrical positions are maximally bimoraic. 2. Verse feet are binary. 3. The most popular Arabic meters are iambic. We begin with a presentation of Prosodic Metrics (§2) followed by individual analyses of the Arabic meters (§3). We then turn to the relative popularity of the meters in two large published corpora, relating frequency directly to rhythm (§4). We then argue against al Xalı#l’s analysis as formalized in Prince 1989 (§5) and end with a brief conclusion (§6). 2. Prosodic Metrics We base our theory of meter on the three claims in (1), which we jointly refer to as Binarity. -

543 Cass Street, Chicago Copyright 1915 by Harriet Monroe

FEBRUARY, 1915 The Chinese Nightingale . Vachel Lindsay Silence Edgar Lee Masters Two Poems Victor Starbuck The Idler—The Poet. The Fisher Lad Francis Buzzell Voices of Women . Margaret Widdemer A Lost Friend—The Net—The Singer at the Gate—The Last Song of Bilitis. A Call in Hell Violet Hunt Dancers Richard Aldington Palace Music Hall—Interlude. Four Poems Orrick Johns Sister of the Rose—The Rain—The Battle of Men and God—The Haunt. Comments and Reviews The Renaissance—Modern German Poetry- Reviews—Our Contemporaries—Notes. 543 Cass Street, Chicago Copyright 1915 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved. VOL. V No. V FEBRUARY, 1915 THE CHINESE NIGHTINGALE A Song in Chinese Tapestries Dedicated to S. T. F. "HOW, how," he said. "Friend Chang," I said, "San Francisco sleeps as the dead— Ended license, lust and play: Why do you iron the night away ? Your big clock speaks with a deadly sound, With a tick and a wail till dawn comes round. While the monster shadows glower and creep, What can be better for man than sleep?" "I will tell you a secret," Chang replied; "My breast with vision is satisfied, And I see green trees and fluttering wings, And my deathless bird from Shanghai sings." [199] POETRY: A Magazine of Verse Then he lit five fire-crackers in a pan. "Pop, pop!" said the fire-crackers, "cra-cra-crack!" He lit a joss-stick long and black. Then the proud gray joss in the corner stirred; On his wrist appeared a gray small bird, And this was the song of the gray small bird: "Where is the princess, loved forever, Who made Chang first of the kings of men?" And the joss in the corner stirred again; And the carved dog, curled in his arms, awoke, Barked forth a smoke-cloud that whirled and broke. -

Writ 205A, Poetry

ENGLISH 200: INTRODUCTION TO POETRY WRITING Fall Semester 2013 Tu/Th 9:30–10:45 PM, Clough Hall 300 CRN: 14521 Dr. Caki Wilkinson Office: Palmer 304 Phone: x3426 Office hours: Tu/W/Th 11:00 AM – noon, and by appt. Email: [email protected] TEXTS Harmon, William, ed. The Poetry Toolkit. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. McClatchy, J.D., ed. The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry. 2nd edition. New York: Vintage Books, 2003. ―As a rule, the sign that a beginner has a genuine original talent is that he is more interested in playing with words than in saying something original; his attitude is that of the old lady, quoted by E.M. Forster—‗How can I know what I think until I see what I say?‘‖ – W.H. Auden COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is designed to help participants broaden their understanding and appreciation of the craft of poetry. Bearing in mind that the English word poetry derives from the Greek poēisis (an act of ―making‖) we will approach writing as a means of producing ideas rather than simply expressing them. Throughout the semester we will be, as Auden put it, ―playing with words,‖ and our work will focus on elements of poetry such as diction, rhythm, imagery, and arrangement. We will read a large sampling of contemporary poetry; we will do a lot of writing, from weekly exercises to polished poems; we will discuss this writing in workshop format and learn how to make it better. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Nine writing exercises Six poems and a final portfolio A poetic catalog consisting of ten reading lists Memorization of fourteen lines of poetry Active participation in workshop and written responses to poems Writing exercises.