Towards an Enlightened and Inclusive Mizo Society Report of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Lunglei District

DISTRICT AGRICULTURE OFFICE LUNGLEI DISTRICT LUNGLEI 1. WEATHER CONDITION DISTRICT WISE RAINFALL ( IN MM) FOR THE YEAR 2010 NAME OF DISTRICT : LUNGLEI Sl.No Month 2010 ( in mm) Remarks 1 January - 2 February 0.10 3 March 81.66 4 April 80.90 5 May 271.50 6 June 509.85 7 July 443.50 8 August 552.25 9 September 516.70 10 October 375.50 11 November 0.50 12 December 67.33 Total 2899.79 2. CROP SITUATION FOR 3rd QUARTER KHARIF ASSESMENT Sl.No . Name of crops Year 2010-2011 Remarks Area(in Ha) Production(in MT) 1 CEREALS a) Paddy Jhum 4646 684716 b) Paddy WRC 472 761.5 Total : 5018 7609.1 2 MAIZE 1693 2871.5 3 TOPIOCA 38.5 519.1 4 PULSES a) Rice Bean 232 191.7 b) Arhar 19.2 21.3 c) Cowpea 222.9 455.3 d) F.Bean 10.8 13.9 Total : 485 682.2 5 OIL SEEDS a) Soyabean 238.5 228.1 b) Sesamum 296.8 143.5 c) Rape Mustard 50.3 31.5 Total : 585.6 403.1 6 COTTON 15 8.1 7 TOBACCO 54.2 41.1 8 SUGARCANE 77 242 9 POTATO 16.5 65 Total of Kharif 7982.8 14641.2 RABI PROSPECTS Sl.No. Name of crops Area covered Production Remarks in Ha expected(in MT) 1 PADDY a) Early 35 70 b) Late 31 62 Total : 66 132 2 MAIZE 64 148 3 PULSES a) Field Pea 41 47 b) Cowpea 192 532 4 OILSEEDS a) Mustard M-27 20 0.5 Total of Rabi 383 864 Grand Total of Kharif & Rabi 8365 15505.2 WATER HARVESTING STRUCTURE LAND DEVELOPMENT (WRC) HILL TERRACING PIGGERY POULTRY HORTICULTURE PLANTATION 3. -

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

World Bank Document

h -- Public Disclosure Authorized gn,un,r- s' t .S *K t ' t~~~~~~~~~~-- i ll E il P \~~~t 4 1- ' Public Disclosure Authorized (na'g HS) zY Wm"y''''S.'f' ;', ', ''' '',''-' '~'0', t'' .SC:''''''''E 3'; , 'r' 6 ~ U Public Disclosure Authorized it ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Public Disclosure Authorized OA 86b3 ' :~~~~~~~~~~~ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTORY BACKGROUND ................................................... 1-1 1.1. PROJECT BACKGROUND ................................................... 1-1 1.2. PROPOSED WORKS FOR BP1 -THE AIZAWL BYPASS . ..................................1-1 1.3. IMPACTS ENVISAGED AND THE CORRIDOR OF IMPACT . ..............................1-4 1.4. SCOPE OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT ................................... 1-6 1.5. THE STUDY METHODOLOGY ................................................................... 1-6 1.6. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ................................................................... 1-7 2.' POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK . ..............................2-1 2.1. IMPLEMENTATION AND REGUALTORY AGENCIES .......................................................... 2-1 2.2. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL CLEARANCE STIPULATIONS ............ 2-1 2.3. GOI/GOM CLEARANCE REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................... 2-2 2.4. WORLD BANK REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................... 2-2 3. THE EXISTING ENVIRONMENT ..................................................................... 3-1 3.1. METEOROLOGICAL CONDITIONS -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

First Sighting of Clouded Leopard Neofelis Nebulosa from the Blue Mountain National Park, Mizoram, India

SCIENTIFIC CORRESPONDENCE CORRESPONDENCE First sighting of clouded leopard Neofelis nebulosa from the Blue Mountain National Park, Mizoram, India The clouded leopard, Neofelis nebulosa in captivity (Figure 1). It resembles the leopard was seen in the primary forest is reported to occur in the forests of marbled cat, Felis marmorata; however, consisting of Quercus spp. and Rhodo- Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, Assam, Myan- while a marbled cat’s total length is dendron spp. near the Phawngpui peak, mar, southern China and Malayan coun- about three feet1, the animal sighted on as well as in secondary forest comprising tries1. Recently, it has been reported each occasion at the BMNP was more bamboo brakes near the Farpak Forest from the northeastern states of Assam, than five feet in total length. I am not Rest House complex. Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, sure whether the same animal was sighted The clouded leopard has been cate- Mizoram and in Sikkim and northern on both the occasions or they were diffe- gorized as vulnerable by the IUCN14 and parts of West Bengal2–5. In Mizoram, rent individuals. During the second inci- also placed in the Appendix I of CITES, the clouded leopard is known as ‘kelral’ dent, the clouded leopard left behind a banning all international commercial deal- in the local dialect. However, there was faint print of its pugmark, 5.5 cm long ing with this animal or parts of it. It is no sight record of this animal from here and 5.9 cm wide, on the cinders dump by included in the Schedule I of the Wildlife till 1997, when it was sighted twice dur- the side of the hutment. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Result 20.1.2020

No.A.12040/1/2019-ZMC Dated Falkawn, the 21st January, 2020 CIRCULAR The following candidates are recommended by the Selection and Recruitment Committee held on the 20th January, 2020 for appointment/engagement to the mentioned posts under Zoram Medical College, Falkawn as shown below: 1. Senior Resident, Department of General Surgery: Regular Basis with remuneration of Level 11 in the Pay Matrix + NPA and other permissible allowance. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Paleti Venu Gopala Reddy T-56, Saikhamakawn, Aizawl The Selection & Recruitment Committee further recommended the following candidates against the post of Senior Resident (General Surgery) to be placed in the reserved panel which shall be valid for a period of one year for filling up the same vacancies only in case candidates in the regular panel are not available for appointment on account of declination of appointment or resignation or death of the recommended candidates. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Zochampuia Ralte Luangmual Venglai, Aizawl 2. Senior Resident, Department of General Medicine: Regular Basis with remuneration of Level 11 in the Pay Matrix + NPA and other permissible allowance. Sl. No. Name Address 1. Dr. Lalthafala V/C-38, Vaivakawn, Aizawl Due to non-availability of candidates, there is no candidate recommended in the reserved panel for the post of Senior Resident in the department of General Medicine. Page 1 of 3 3. Statistician cum Tutor/Demonstrator, Department of Community Medicine: Regular Basis with remuneration of Academic Level 10 in the Pay Matrix and -

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Displaced Brus from Mizoram in Tripura: Time for Resolution

Displaced Brus from Mizoramin Tripura: Time for Resolution Brig SK Sharma Page 2 of 22 About The Author . Brigadier Sushil Kumar Sharma, YSM, PhD, commanded a Brigade in Manipur and served as the Deputy General Officer Commanding of a Mountain Division in Assam. He has served in two United Nation Mission assignments, besides attending two security related courses in the USA and Russia. He earned his Ph.D based on for his deep study on the North-East India. He is presently posted as Deputy Inspector General of Police, Central Reserve Police Force in Manipur. http://www.vifindia.org ©Vivekananda International Foundation Page 3 of 22 Displaced Brus from Mizoram in Tripura: Time for Resolution Abstract History has been witness to the conflict-induced internal displacement of people in different states of Northeast India from time to time. While the issues of such displacement have been resolved in most of the North-eastern States, the displacement of Brus from Mizoram has remained unresolved even over past two decades. Over 35,000 Brus have been living in six makeshift relief camps in North Tripura's Kanchanpur, areas adjoining Mizoram under inhuman conditions since October 1997. They had to flee from their homes due to ethnic violence in Mizoram. Ever since, they have been confined to their relief camps living on rations doled out by the state, without proper education and health facilities. Called Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), some of the young Brus from these camps have joined militant outfits out of desperation. There have been several rounds of talks among the stakeholders without any conclusive and time-bound resolutions. -

Distance Education

DISTANCE EDUCATION MA [Education] Second Semester EDCN 803C [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Sitesh Saraswat Reader, Bhagwati College of Education, Meerut Author: Neeru Sood Copyright © Reserved, 2016 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT. LTD. E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 • Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 • Website: www.vikaspublishing.com • Email: [email protected] SYLLABI-BOOK MAPPING TABLE Distance Education Syllabi Mapping in Book Unit - I Distance Education: Significance, Meaning and Characteristics, Unit 1: Introduction to Distance Present status of Distance Education. -

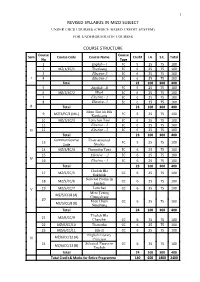

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C.