Gothic Structural Experimentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Contents Inhalt

34 Rome, Pantheon, c. 120 A.D. Contents 34 Rome, Temple of Minerva Medica, c. 300 A.D. 35 Rome, Calidarium, Thermae of Caracalla, 211-217 A.D. Inhalt 35 Trier (Germany), Porta Nigra, c. 300 A.D. 36 NTmes (France), Pont du Gard, c. 15 B.C. 37 Rome, Arch of Constantine, 315 A.D. (Plan and elevation 1:800, Elevation 1:200) 38-47 Early Christian Basilicas and Baptisteries Frühchristliche Basiliken und Baptisterien 8- 9 Introduction by Ogden Hannaford 40 Rome, Basilica of Constantine, 310-13 41 Rome, San Pietro (Old Cathedral), 324 42 Ravenna, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, c. 430-526 10-19 Great Buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia 42 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, 534-549 Grosse Bauten Ägyptens, Mesopotamiens und Persiens 43 Rome, Sant' Agnese Fuori Le Mura, 7th cent. 43 Rome, San Clemente, 1084-1108 12 Giza (Egypt), Site Plan (Scale 1:5000) 44 Rome, Santa Costanza, c. 350 13 Giza, Pyramid of Cheops, c. 2550 B.C. (1:800) 44 Rome, Baptistery of Constantine (Lateran), 430-440 14 Karnak (Egypt), Site Plan, 1550-942 B.C. (1:5000) 44 Nocera (Italy), Baptistery, 450 15 Abu-Simbel (Egypt), Great Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1250 B.C. 45 Ravenna, Orthodox Baptistery, c. 450 (1:800, 1:200) 15 Mycenae (Greece), Treasury of Atreus, c. 1350 B.C. 16 Medinet Habu (Egypt), Funerary Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1175 B.C. 17 Edfu (Egypt), Great Temple of Horus, 237-57 B.C. 46-53 Byzantine Central and Cross-domed Churches 18 Khorsabad (Iraq), Palace of Sargon, 721 B.C. -

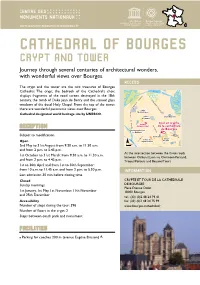

Crypt and Tower of Bourges Cathedral

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr CATHEDRAL OF BOURGES CRYPT AND TOWER Journey through several centuries of architectural wonders, with wonderful views over Bourges. ACCESS The crypt and the tower are the two treasures of Bourges Cathedral. The crypt, the bedrock of the Cathedral’s choir, displays fragments of the rood screen destroyed in the 18th century, the tomb of Duke Jean de Berry and the stained glass windows of the ducal Holy Chapel. From the top of the tower, there are wonderful panoramic views over Bourges. Cathedral designated world heritage site by UNESCO. RECEPTION Subject to modification. Open 2nd May to 31st August: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.45 p.m. At the intersection between the three roads 1st October to 31st March: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. between Orléans/Lyon via Clermont-Ferrand, and from 2 p.m. to 4.45 p.m. Troyes/Poitiers and Beaune/Tours 1st to 30th April and from 1st to 30th September: from 10 a.m. to 11.45 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. INFORMATION Last admission 30 min before closing time. Closed CRYPTE ET TOUR DE LA CATHÉDRALE Sunday mornings DE BOURGES Place Étienne Dolet 1st January, 1st May, 1st November, 11th November 18000 Bourges and 25th December tel.: (33) (0)2 48 24 79 41 Accessibility fax: (33) (0)2 48 24 75 99 Number of steps during the tour: 396 www.bourges-cathedrale.fr Number of floors in the crypt: 2 Steps between coach park and monument FACILITIES Parking for coaches 200 m (avenue Eugène Brisson) NORTH WESTERN FRANCE CENTRE-LOIRE VALLEY / CRYPT AND TOWER OF BOURGES -

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, the University of Iowa Art

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, The University of Iowa Art Building West, North Riverside Drive, Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone: 319-335-1762 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY Education Princeton University. Ph.D., Architectural History, 1996; M.A. 1993. University of California, Santa Cruz. M.S., Physics, 1990. Passed qualifying exams for candidacy to Ph.D., 1991. Harvard University. B.A. CuM Laude, Physics, 1989. Granville High School, Granville, Ohio. Graduated Valedictorian, 1985. Professional and academic positions University of Iowa. Professor. Fall 1998 to Spring 2004 as Assistant Professor; promoted May 2004 to Associate Professor; promoted May 2012 to Full Professor. Florida Atlantic University. Assistant Professor. Fall 1997-Spring 1998. Sewanee, The University of the South. Visiting Assistant Professor. Fall 1996-Spring 1997. University of Connecticut. Visiting Lecturer. Fall 1995. Washington Cathedral. Technical Consultant. Periodic employment between 1993 and 1995. SCHOLARSHIP I: PUBLICATIONS Books (sole author) 1) Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 562 pages. 2) The Geometry of Creation: Architectural Drawing and the Dynamics of Gothic Design (FarnhaM: Ashgate, 2011), 462 pages. The Geometry of Creation has been reviewed by Mailan Doquang in Speculum 87.3 (July, 2012), 842-844, by Stefan Bürger in Sehepunkte, www.sehepunkte.de/2012/07/20750.htMl, by Eric Fernie in The Burlington Magazine CLV, March 2013, 179-80, by David Yeomans in Construction History Society, Jan 2013, 23-25, by Paul Binski in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 166, 2013, 212-14, by Paul Crossley in Architectural History, 56, 2013, 13-14, and by Michael Davis in JSAH 73, 1 (March, 2014), 169-171. -

On the Characteristic Interpenetrations of the Flamboyant Style

ON THE CHARACTERISTIC INTERPENETRATIONS OF THE FLAMBOYANT STYLE. BY R. WILLIS, M. A. F. R. S. &c. JACKSONIAN PROFESSOR IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE, AND HONORARY MEMBER OF THE INSTITUTE OF BRITISH ARCHITECTS. AMONGS~ other characters that distinguish the later s.tyles of Gothic on the contment from our own contemporary Perpendicular style, there may be observed a much greater and more fanciful intricacy of parts, contrived apparently more with a view to display difficulties overcome than beauties of art. Hence an excessive employment of interpenetrating surfaces, especially in the Flamboyant Style. In English examples a moulding may sometimes be found which penetrates some projecting member, and appears on the other side, as for example in jig. I, which represents a portion of the base of one of the turrets of King's College Chapel. The string moulding at 4. A appears on the face of the plinths of the angle buttresses as if it had penetrated their substance, or rather the whole arrangement of the bases of the' turrets and of the buttresses respectively, appears to suggest a mutual pene tration or interpenetration of the two. Examples of this kind are not common in English work, and are confined merely to the interferences of adjacent necessary members of the architectural arrangement. In the Flamboyant style, on the contrary, interpenetration occurs so frequently as to con .. EgJ. stitute a characteristic, and is produced not merely between two neighbouring architectural members, but new members are also introduced for the mere purpose of showing interpenetrations. Thus, as we shall see, two different bases may be given to the same shaft, or even two or more different turrets with pinnacles may be placed in an identical M 82 WILLIS ON THE INTERPENETRATIONS OF position on the plan, and made to interfere and interpenetrate throughout their entire height from the base upwards in a manner that defies description, and can only be illustrated by drawings. -

The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral Author: Seong-Woo Hong, Professor, Kyungwoon University Subject: Structural Engineering Keyword: Structure Publication Date: 2004 Original Publication: CTBUH 2004 Seoul Conference Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Seong-Woo Hong The Analysis on the Collapse of the Tallest Gothic Cathedral Seong-Woo Hong1 1 Professor, School of Architecture, Kyungwoon University Abstract At the end of the twelfth century, a new architectural movement began to develop rapidly in the Ile-de-France area of France. This new movement differed from its antecedents in its structural innovations as well as in its stylistic and spatial characteristics. The new movement, which came to be called Gothic, is characterized by the rib vault, the pointed arch, a complex plan, a multi-storied elevation, and the flying buttress. Pursuing the monumental lightweight structure with these structural elements, the Gothic architecture showed such technical advances as lightness of structure and structural rationalism. However, even though Gothic architects or masons solved the technical problems of building and constructed many Gothic cathedrals, the tallest of the Gothic cathedral, Beauvais cathedral, collapsed in 1284 without any evidence or document. There have been two different approaches to interpret the collapse of Beauvais cathedral: one is stylistic or archeological analysis, and the other is structural analysis. Even though these analyses do not provide the firm evidence concerning the collapse of Beauvais cathedral, this study extracts some confidential evidences as follows: The bay of the choir collapsed and especially the flying buttress system of the second bay at the south side of the choir was seriously damaged. -

É an Installation by JR #Aupanth·On Ê

Press release, 25 February 2014 The CM N is inviting JR to create a participatory work at the Pantheon çTo the Pantheon!é an installation by JR #AuPanth·on ê www.au-pantheon.fr Press officer: Camille Boneu ê +33 (0)1 44 61 21 86 ê camille.boneu@ monuments-nationaux.fr çTo the Pantheon!é An installation by JR The restoration work currently being carried out on the Pantheon is one of the largest projects in Europe. The purpose of the current phase is to consolidate and fully restore the dome. A vast self-supporting scaffolding system ê a great technical feat ê has been built around the dome and will remain in place for two years. Last October the President of the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Philippe Bélaval, presented the President of the French Republic with a report on the role of the Pantheon in promoting the values of the Republic. The title of this public report was “Pour faire entrer le peuple au Panthéon” (Getting people into the Pantheon), and it contains suggestions on how to make the monument more attractive, encourage French people to truly identify with it, and give it a greater role in Republican ceremonies. In order to give concrete form to these proposals, which have since been approved by the public authorities, the CMN has chosen to ask a contemporary artist to carry out a worldwide project embodying the values of this monument, which is so emblematic of the French Republic. Hence for the first tim e the worksite hoardings installed around a national m onum ent will be used to present a contem porary artistic venture instead of a lucrative advertising cam paign. -

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook Define these terms: Key Cultural & Religious Terms: Scholasticism, disputatio, indulgences, lux nova, Annunciation, Visitation, opere francigeno, opus modernum Key Art Terms: stained glass, glazier, flashing, cames, leading, plate tracery, bar tracery, fleur‐de‐lis, Rayonnant, Flamboyant, mullions, moralized Bible, breviary, Perpendicular style, ambo, altarpiece, triptych, pieta Key Architectural Terms: altar frontal, rib vault, armature, webs, pointed arch, jamb figures, trumeau, triforium, oculus, flying buttress, pinnacle, vaulting web, diagonal rib, transverse rib, springing, clerestory, lancet, nave arcade, compound pier (cluster pier), shafts (responds), ramparts, battlements, crenellations, merlons, crenels, fan vaults, pendants, Gothic Revival, Hallenkirche (hall church) Exercises for Study: 1. Describe the key architectural features introduced in the French cathedral design in the Gothic era. 2. Describe features that make English Gothic cathedrals distinct from their French or German counterparts. 3. Describe the late Gothic Rayonnant and Flamboyant styles, and give examples of each. 4. Compare and contrast the following pairs of artworks, using the points of comparison as a guide. A. Old Testament kings and queen, jamb statues, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐7); Virgin and Child (Virgin of Paris), Notre‐Dame, Paris (Fig. 13‐26) • Dates: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: B. Saint Theodore, jamb statue, left portal, Porch of the Martyrs, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐18); Naumburg Master, Ekkehard and Uta, Naumburg Cathedral (Fig. 13‐48): • Dates: • Subjects: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: C. Interior of Saint Elizabeth, Marburg, Germany (Fig. 13‐53); Interior of Laon Cathedral, Laon, France (Fig. 13‐9) • Dates & locations: • Nave elevation: • Aisles: • Ceiling vaults: • Other architectural features: Chapter Questions: 1. -

The Cathedral of Bourges

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 6 (2011): Jennings CP1-10 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING The Cathedral of Bourges: A Witness to Judeo-Christian Dialogue in Medieval Berry Margaret Jennings, Boston College Presented at the “Was there a „Golden Age‟ of Christian-Jewish Relations?” Conference at Boston College, April 2010 The term “Golden Age” appears in several contexts. In most venues, it both attracts and inspires controversy: Is the Golden Age, as technology claims, the year following a stunning break- through, now available for use? Is it, as moralists would aver, a better, purer time? Can it be identified, as social engineers would hope, as an epoch of heightened output in art, science, lit- erature, and philosophy? Does it portend, in assessing human development, an extended period of progress, prosperity, and cultural achievement? Factoring in Hesiod‟s and Ovid‟s understand- ing that a “Golden Age” was an era of great peace and happiness (Works and Days, 109-210 and Metamorphoses I, 89-150) is not particularly helpful because, as a mythological entity, their “golden age” was far removed from ordinary experience and their testimony is necessarily imag- inative. In the end, it is probably as difficult to define “Golden Age” as it is to speak of interactions between Jews and Christians in, what Jonathan Ray calls, “sweeping terms.” And yet, there were epochs when the unity, harmony, and fulfillment that are so hard to realize seemed almost within reach. An era giving prominence to these qualities seems to deserve the appellation “golden age.” Still, if religious differences characterize those involved, the possibility of disso- nance inevitably raises tension. -

Outstanding Heritage Sites - a Resource for Territories Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, Nicolas Senil

Outstanding heritage sites - A resource for territories Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, Nicolas Senil To cite this version: Magali Talandier, Françoise Navarre, Laure Cormier, Pierre-Antoine Landel, Jean-François Ruault, et al.. Outstanding heritage sites - A resource for territories. Editions du PUCA, 2019, Recherche, 978-2-11-138177-3. halshs-02298543 HAL Id: halshs-02298543 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02298543 Submitted on 26 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Outstanding heritage sites condense issues pertaining to economic development, financial management, governance, appropriation and preservation, affecting the territories which they are part of. These tensions, given free rein, would undermine the purpose served by the sites as well as their sustainability. In this context and after the analysis stage, the publication lays down the necessary conditions for these remarkable sites to constitute resources for the territories hosting them, and -

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus Charles Anthony Stewart Though the Byzantine Empire dissolved over five hundred years ago, its monuments still stand as a testimony to architectural ingenuity. Because of alteration through the centuries, historians have the task of disentangling their complex building phases. Chronological understanding is vital in order to assess technological “firsts” and subsequent developments. As described by Edson Armi: Creative ‘firsts’ often are used to explain important steps in the history of art. In the history of medieval architecture, the pointed arch along with the…flying buttress have receive[d] this kind of landmark status.1 Since the 19th century, scholars have documented both flying buttresses and pointed arches on Byzantine monuments. Such features were difficult to date without textual evidence. And so these features were assumed to have Gothic influence, and therefore, were considered derivative rather than innovative.2 Archaeological research in Cyprus beginning in 1950 had the potential to overturn this assumption. Flying buttresses and pointed arches were discovered at Constantia, the capital of Byzantine Cyprus. Epigraphical evidence clearly dated these to the 7th century. It was remarkable that both innovations appeared together as part of the reconstruction of the city’s waterworks. In this case, renovation was the mother of innovation. Unfortunately, the Cypriot civil war of 1974 ended these research projects. Constantia became inaccessible to the scholarly community for 30 years. As a result, the memory of these discoveries faded as the original researchers moved on to other projects, retired, or passed away. In 2003 the border policies were modified, so that architectural historians could visit the ruins of Constantia once again.3 Flying Buttresses in Byzantine Constantia Situated at the intersection of three continents, Cyprus has representative monuments of just about every civilization stretching three millennia. -

Chartres and High Gothi 1190+ the “High Gothic” Cathedrals

Chartres and High Gothi 1190+ The “High Gothic” Cathedrals: Chartres, 1194+ Soissons, 1191+ (?) Bourges, 1194 Reims, 1210 Amiens, 1220 Beauvais, 1225 108 116 137+ gigantism in Gothic Architecture Bourges Cathedral, begun 1194 Chartres Cathedral, begun 1194 Soissons Chartres Bourges The “High Gothic Revolution:” 3 stories clerestory as tall as arcade (but not Bourges) quadripartite vaults (mostly) Chartres, 116’, 1194+ Soissons, 97’,1191+ Bourges, 118’, 1195+ 1. Simplification • 3-story elevations • Quadripartite vaults • Flying buttresses 2. Monumentality- buildings over 110’ tall 3. Assertiveness – (down go the Gallo-Roman Walls!) Chartres Cathedral, 1194 + The tunic of the Virgin: the sancta camisa, given to cathedral 876 Le puits des Saints forts Ergotism - St. Anthony’s fire Bishop Fulbert (1007-1028) dedicates the cathedral of 1020 West towers rebuilt after fire of 1134 with portals of c. 1145 Royal portals 1145 The foundations of Fulbert’s cathedral of 1020 (in grey) underneath the present cathedral (in orange) rebuilt in 1194+ Fulbert’s cathedral of 1020 Original location of portals Final location of ROYAL portals Christ in Majesty The Virgin THE ROYAL Ascension PORTALS OF The Royal CHARTRES Portal: 1145 c. 1145 Bishop Fulbert’s Cathedral of 1020, built around older Carolingian church The puit des Saints forts Flamboyant style N. spire (16th century) South tower North c. 1140 Tower 1134 1194 + Royal portals and west windows, c. 1145 Chartres, the town The bishop had full jurisdiction until c 1020’s, then king gave the county of