Washington State Public Transportation Washington Authorities Transit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary

Final Report New Haven Hartford Springfield Commuter Rail Implementation Study 2 Existing Conditions Chapter 2 Existing Conditions Summary This chapter is a summary of the existing conditions report, necessary for comprehension of the remaining chapters. The entire report can be found in Appendix B of this report. 2.1 Existing Passenger Services on the Line The only existing passenger rail service on the Springfield Line is a regional service operated by Amtrak. Schedules for alternatives in Chapter 3 and the Recommended Action in Chapter 4 include current Amtrak service. Most Amtrak service on the line is shuttle trains, running between Springfield and New Haven, where they connect with other Amtrak Northeast Corridor trains. One round-trip train each day operates through the corridor to Boston to the north and Washington to the south. One round trip train each day operates to and from St. Albans, Vermont from New Haven. The trains also permit connections at New Haven with Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor (Washington to Boston) service, as well as Metro North service to New York, and Shore Line East local commuter service to New London. Departures are spread throughout the day, with trains typically operating at intervals of two to three hours. Springfield line services are designed as extensions of Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor service, and are not scheduled to serve local commuter trips (home to work trips). The Amtrak fare structure was substantially reduced in price since this study began. The original fare structure from November 2002 was shown in the existing conditions report, which can be found in Appendix B. -

Transit Service Design Guidelines

Transit Service Design Guidelines Department of Rail and Public Transportation November 2008 Transit Service Design Guidelines Why were these guidelines for new transit service developed? In FY2008 alone, six communities in Virginia contacted the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation about starting new transit service in their community. They and many other communities throughout Virginia are interested in learning how new transit services can enhance travel choices and mobility and help to achieve other goals, such as quality of life, economic opportunity, and environmental quality. They have heard about or seen successful transit systems in other parts of the state, the nation, or the world, and wonder how similar systems might serve their communities. They need objective and understandable information about transit and whether it might be appropriate for them. These guidelines will help local governments, transit providers and citizens better understand the types of transit systems and services that are available to meet community and regional transportation needs. The guidelines also help the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) in making recommendations to the Commonwealth Transportation Board for transit investments, by 1) providing information on the types of systems or services that are best matched to community needs and local land use decisions, and 2) ensuring that resources are used effectively to achieve local, regional, and Commonwealth goals. Who were these guidelines developed for? These guidelines are intended for three different audiences: local governments, transit providers and citizens. Therefore, some will choose to read the entire document while others may only be interested in certain sections. -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Intercity Bus Program Section 5311 (F) Presented By: FTA Region 4 Staff Lorna Wilson, HQ Juan Morrison, HQ

Federal Transit Administration Intercity Bus Program Section 5311 (f) Presented by: FTA Region 4 Staff Lorna Wilson, HQ Juan Morrison, HQ Federal Transit Administration OBJECTIVE Support the connection between nonurbanized areas and the larger regional or national system of intercity bus service. Support services to meet the intercity travel needs of residents in nonurbanized areas. Support the infrastructure of the intercity bus network through planning and marketing assistance and capital investment in facilities. FTA encourages States to use the funding under 49 U.S.C. 5311(f) to support these national objectives, as well as priorities determined by the State. FTA TPM ver3.1 2 GOVERNOR’S CERTIFICATION A State is required to expend at least 15 percent of its apportionment for an intercity bus program, unless “the chief executive officer of the State certifies to the Secretary of Transportation, after consultation with affected intercity bus service providers, that the intercity bus service needs of the State are being met adequately.” FTA TPM ver3.1 3 INTERCITY BUS The legislative history indicates that the assessment of intercity bus needs be made “relative to other rural needs in the State.” A State certifying that its needs are adequately met must demonstrate that it has assessed statewide intercity mobility needs no more than four years before the date of the certification The State must document in the State Management Plan (SMP) its consultation process and any process that it develops for periodically assessing statewide -

Reservations PUBLISHED Overview 30 March 2015.Xlsx

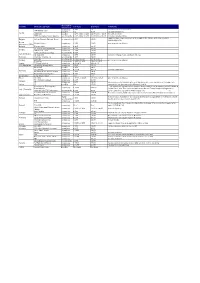

Reservation Country Domestic day train 1st Class 2nd Class Comments Information compulsory € 8,50 n.a. on board only; free newspaper WESTbahn trains possible n.a. € 5,00 via www.westbahn.at Austria ÖBB trains possible € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 free wifi on rj-trains ÖBB Intercitybus Graz-Klagenfurt recommended € 3,00 online / € 3,50 € 3,00 online / € 3,50 first class includes drinks supplement per single journey. Can be bought in the station, in the train or online: Belgium to/from Brussels National Airport no reservation € 5,00 € 5,00 www.belgianrail.be Bosnia- Regional trains compulsory € 1,50 € 1,50 price depends on distance Herzegovina (ZRS) Bulgaria Express trains compulsory € 0,25 € 0,25 IC Zagreb - Osijek/Varazdin compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 Croatia ICN Zagreb - Split compulsory € 1,00 € 1,00 IC/EC (domestic journeys) recommended € 2,00 € 2,00 Czech Republic SC SuperCity compulsory € 8,00 € 8,00 includes newspaper and catering in 1st class Denmark InterCity / InterCity Lyn recommended € 4,00 € 4,00 InterCity recommended € 1,84 to €5,63 € 1,36 to € 4,17 Finland price depends on distance Pendolino recommended € 3,55 to € 6,79 € 2,63 to € 5,03 France TGV and Intercités compulsory € 9 to € 18 € 9 to € 18 FYR Macedonia IC 540/541 Skopje-Bitola compulsory € 0,50 € 0,50 EC/IC/ICE possible € 4,50 € 4,50 ICE Sprinter compulsory € 11,50 € 11,50 includes newspapers Germany EC 54/55 Berlin-Gdansk-Gdynia compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Berlin-Warszawa Express compulsory € 4,50 € 4,50 Great Britain Long distance trains possible Free Free Greece Inter City compulsory € 7,10 to € 20,30 € 7,10 to € 20,30 price depends on distance EC (domestic jouneys) compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 Hungary IC compulsory € 3,00 € 3,00 when purchased in Hungary, price may depend on pre-sales and currency exchange rate Ireland IC possible n/a € 5,00 reservations can be made online @ www.irishrail.ie Frecciarossa, Frecciargento, → all compulsory and optional reservations for passholders can be purchased via Trenitalia at compulsory € 10,00 € 10,00 Frecciabianca "Global Pass" fare. -

Concord Coach (NH) O Dartmouth Coach (NH) O Peter Pan Bus Lines (MA)

KFH GROUP, INC. 2012 Vermont Public Transit Policy Plan INTERCITY BUS NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND POLICY OPTIONS White Paper January, 2012 Prepared for the: State of Vermont Agency of Transportation 4920 Elm Street, Suite 350 —Bethesda, MD 20814 —(301) 951-8660—FAX (301) 951-0026 Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Background and Policy Context......................................................................... 1-1 Policy Context...................................................................................................................... 1-1 Chapter 2: Inventory of Existing Intercity Passenger Services.......................................... 2-1 Intercity Bus......................................................................................................................... 2-1 Impacts of the Loss of Rural Intercity Bus Service......................................................... 2-8 Intercity Passenger Rail.................................................................................................... 2-11 Regional Transit Connections ......................................................................................... 2-11 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 2-13 Chapter 3: Analysis of Intercity Bus Service Needs............................................................ 3-1 Demographic Analysis of Intercity Bus Needs............................................................... 3-1 Public Input on Transit Needs ....................................................................................... -

Intercity High-Speed Railway Systems • Economic Growth and Increased Employment

Low Carbon Green Growth Roadmap for Asia and the Pacific FACT SHEET If designed well, high-speed railway systems contribute towards: • Improved air quality and lower greenhouse gas emissions4 Intercity high-speed railway systems • Economic growth and increased employment Challenges to using high-speed railway High-speed railway explained • Estimating annual ridership during feasibility stage analysis (and thus returns, including greenhouse gas Definitions of a high-speed railway system vary, but a common one is a rail system designed for maximum train reduction) can be difficult, especially when developments in other transportation modes (air and auto speeds that exceed 200 km per hour for upgraded tracks and 250 km per hour for new tracks. High-speed rail is mobile) are uncertain generally used for intercity transport rather than urban transport. • High investment costs for buying the needed land and building the lines and trains • Long period of construction time and for reaping payback Performance, evaluated Limitations Capacity Approximately 1,000 persons per vehicle. Double-decker trains • High-speed rail lines, once built, are very inflexible. Corridors to be developed must be heavily studied to increase the capacity but also increase drag, and thus increase the determine if the return is likely to be eco-efficient. amount of energy needed. • Increasing train speed requires considerably more electricity. If power is sourced from polluting technologies and/or if load factors are low, high-speed rail can actually exacerbate rather than mitigate Geographical range There is no limit in expanding the line, as long as the demand is high. Generally, high-speed rail can compete with airplane trips of greenhouse gas emissions. -

Why Some Airport-Rail Links Get Built and Others Do Not: the Role of Institutions, Equity and Financing

Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel S.M. in Engineering Systems- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010 Vordiplom in Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen- Universität Karlsruhe, 2007 Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Political Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2011 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2011. All rights reserved. Author . Department of Political Science October 12, 2010 Certified by . Kenneth Oye Associate Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Roger Peterson Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel Submitted to the Department of Political Science On October 12, 2010, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Political Science Abstract The thesis seeks to provide an understanding of reasons for different outcomes of airport ground access projects. Five in-depth case studies (Hongkong, Tokyo-Narita, London- Heathrow, Chicago- O’Hare and Paris-Charles de Gaulle) and eight smaller case studies (Kuala Lumpur, Seoul, Shanghai-Pudong, Bangkok, Beijing, Rome- Fiumicino, Istanbul-Atatürk and Munich- Franz Josef Strauss) are conducted. The thesis builds on existing literature that compares airport-rail links by explicitly considering the influence of the institutional environment of an airport on its ground access situation and by paying special attention to recently opened dedicated airport expresses in Asia. -

Regional Rail

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES * SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TERMINALS E and F 37, 108, 115 )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU AIRPORT INFORMATION AIRPORT TERMINALS C and D 37, 108, 115 =RQH Ê*Ë6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 $0 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV( ) TERMINAL A - EAST and WEST AIRPORT TERMINAL B 37, 108, 115 REGIONAL RAIL AIRPORT $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV& ' D American Airlines International & Caribbean AIRPORT TERMINAL A EAST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO% British Airways AIRPORT TERMINAL A WEST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO$ LINE EASTWICK (DVWZLFN Qatar Airways 37, 68, 108, 115 To/From Center City Philadelphia D 8511 Bartram Ave & D 3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ Eastern Airlines PENN MEDICINE STATION & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ ' TERMINAL B 3149 Convention Blvd 40, LUCY & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ ' 215-580-6565 Effective September 5, 2021 & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ ' American Airlines Domestic & Canadian service MFL, 9, 10, 11, 13, 30, 31, 34, 36, 30th STREET STATION & D7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ The Philadelphia Marketplace 44, 49, 62, 78, 124, 125, LUCY, 30th & Market Sts Amtrak, NJT Atlantic City Rail Line • Airport Terminals E and F D :D\QH-XQFWLRQ ² ²² ²² ²² ² ² ² Airport Marriott Hotel SUBURBAN STATION MFL, BSL, 2, 4, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, DD)HUQ5RFN7& ² 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 48, 62, • Airport Terminals C and D 16th St -

2018 Annual Report & Transit Development Plan 2019 – 2024

2018 Annual Report & Transit Development Plan 2019 – 2024 Prepared by: Joseph Clark, Director of Transit Services Adopted in Public Hearing by LPTBA Board: October 15, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 1: ORGANIZATION ........................................................................................................ 4 SECTION 2: BASE FACILITY ........................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 3: SERVICE CHARACTERISTICS .................................................................................. 5 SECTION 4: SERVICE CONNECTIONS ........................................................................................ 10 SECTION 5: ACTIVITIES AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2018 ............................................................... 11 SECTION 6: PROPOSED ACTION STRATEGIES 2019 - 2024 ..................................................... 17 SECTION 7: PROPOSED CHANGES 2019 – 2024 ........................................................................ 23 SECTION 8: CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM 2019 - 2024 ............................................... 30 SECTION 9: OPERATING REVENUES AND EXPENSES: 2019 – 2024 ....................................... 34 INTRODUCTION As a requirement of RCW 35.58.2795, Twin Transit has prepared and submitted this Annual Report for 2018 and a subsequent Transit Development Plan (TDP) for years 2019 through -

Passenger Rail Primer

Passenger Rail Primer Thurston Passenger Rail Workgroup November 2005 Passenger Rail Characteristics This document is intended as a primer introducing and familiarizing the reader with the basic definitions of passenger rail and providing a comparison of common transit services in 2005. It was developed to facilitate a discussion of passenger rail and other transit options in the Thurston Region, in preparation of a regional rail plan. In the next section, Passenger Rail Overview, the fundamental characteristics of light rail, commuter rail and intercity rail are covered. Complementary and Alternative Transit Options (primarily common bus transit choices) provides a wider transit context within which the passenger rail modes coordinate and compete. After investigating transit options individually, they are compared and contrasted in a chart of their characteristics, Summarizing the Continuum of Services. Other Rail Transit Technologies provides a brief overview of less extensively used rail options and the Appendices provide additional details and information. Additional resources the reader may want to consult include: • The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) website at www.apta.com • The Victoria Transportation Policy Institute (VTPI) website at www.vtpi.org • Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) website at www.bts.gov Passenger Rail Overview Introduction Passenger rail modes may be distinguished from one another based on a variety of characteristics – level of service, technology, right-of-way and operations. These characteristics are discussed in more detail in the other sections of this chapter. Like other transit services, however, in the most basic sense passenger rail modes break down by three distinct geographies – local, regional, and statewide or interstate.