Transit Service Design Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ucr Rides Free with the Token Transit

UCR RIDES FREE WITH THE PLAN YOUR TRIP TODAY VISIT US TOKEN TRANSIT APP RiversideTransit.com The Riverside Transit Agency has switched to a contactless fare system available through the Token Transit app. UCR students and staff will no longer swipe their R’Card to board the RTA bus. To get your free transit pass CONTACT US you will be required to log in to UCR’s Transportation Services website and Customer Information Center enroll in the U-PASS Program. Once registered, you will receive your free pass via the Token Transit app for unlimited rides anywhere RTA buses go, at (951) 565-5002 anytime they operate. And yes, you can take your bike or skateboard with you on the bus. WE’RE OPEN Getting your pass is easy. After you enroll online, UCR will send your registration to RTA. Staff passes will be processed immediately and within Until 10 p.m. every day three to five days you will receive a text message from Token Transit with a link to download the pass. After that, simply use your phone’s mobile pass whenever you board and enjoy the ride. Student passes will be issued STAY SAFE beginning September 24 and valid through the end of the term. RTA is asking customers to With trained drivers, clean vehicles and a commitment to customer safety, practice social distancing, say hello to a better way to travel. Plus, there’s comfortable seating, free wear face masks and travel for Wi-Fi service and USB charging ports to make your trip even better. -

4606 – Hampton Roads Transit (HRT) Passes

No. 4606 Rev.: 5 Policies and Procedures Date: December 14, 2017 Subject: Hampton Roads Transit (HRT) Passes 1. Purpose .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy ........................................................................................................................ 1 3. Responsibilities ......................................................................................................... 2 4. Procedures ............................................................................................................... 2 4.1 Obtaining the HRT GoSemester Pass .............................................................. 2 4.2 Obtaining Para-Transit Passes ......................................................................... 2 4.3 Staff and Non-Credit Student Purchase of HRT Passes .................................. 2 4.4 Use of HRT Services ........................................................................................ 2 4.5 Lost, Stolen, and/or Damaged HRT Passes ..................................................... 3 5. Definitions ................................................................................................................. 3 6. References ............................................................................................................... 3 7. Review Periodicity and Responsibility ...................................................................... 3 8. Effective Date and Approval .................................................................................... -

N E W Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) from MISTER Ltd., Poland

www.mist-er.com, [email protected] N E W Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) from MISTER Ltd., Poland Albert Einstein : "Imagination is more important than knowledge." Metropolitan Individual System of Transportation on an Elevated Rail Metropolitan Individual System of Transportation on an Elevated Rail PRT development proposal and business opportunity for the 1-st city to build a MISTER system MISTER Ltd ul. Niedzialkowskiego 1/4 45−085 Opole Poland Phone: +48 (0) 793 044 555 [email protected] www.mist-er.com Index • Introduction • The Problem • Our Solution • Company and Team • Competition • The Numbers • Prototype - Poland • Money and Business MISTER prototype demonstrated • Technical Issues in Opole City square in Sept • Summary 2007 3 USA proposal 2008-11 www.mist-er.com Introduction Elevator Message: “MISTER is the answer for every city in the world with traffic jams and transportation problems” MISTER offers: • A new and highly innovative solution MISTER vehicle, track and • A patented version of PRT station design © • Several advantages over other PRT designs • An opportunity for excellent ROI cia ownership interest in a city system as well as a global company 4 USA proposal 2008-11 www.mist-er.com Business offer and city benefits Introduction 1. $50 million for 5 km (3 miles) pilot system and certification track within 2-3 years (less than an average city parking structure) 2. Return of entire investment within 2 to 5 years of operation start. 3. Very limited risk and cost, as compared to investing in current solutions like parkings, infrastructure and transit systems (bus, rail). 4. -

American Maglev Technology (AMT) Proposal

American Maglev Technology (AMT) Proposal: Staff Review and Recommendation Approved by the MetroPlan Orlando Board at the meeting on December 12, 2012 American Maglev Technology (AMT) Proposal: Staff Review and Recommendation Background American Maglev Technology (AMT) has proposed to build, operate and maintain a privately- financed transit project in the Orlando metropolitan area with no public funding. The 40-mile project has an estimated capital cost of $800 million. The project is a fully automatic train system that is powered by magnetic levitation, or maglev technology. This technology lifts the vehicle from the guideway and provides directional motion. The first phase of the proposed system would operate between the Orange County Convention Center/International Drive area (utilizing the planned intermodal center) and Orlando International Airport with stops at The Florida Mall and the Sand Lake Road SunRail Station. Subsequent phases would include stations in the Lake Nona/Medical City area and along the Osceola Parkway corridor leading to Walt Disney World. AMT has spearheaded efforts thus far to advance the implementation of this project. However, the intention is to form a new publicly traded company called Florida EMMI, Inc. (Florida Environmental Mitigation and Mobility Initiative) that will design, build, finance, operate and maintain the project. At that point, AMT will become the company’s maglev technology provider. Florida EMMI, Inc. will bring together an array of strategic partners and more than 120 private companies, some of which are well-known in the transportation industry. The new company will be based here in Central Florida with an advisory board that includes some prominent individuals from our region. -

The Relationship Between Safety, Capacity, and Operating Speed on Bus Rapid Transit

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SAFETY, CAPACITY, AND OPERATING SPEED ON BUS RAPID TRANSIT NICOLAE DUDUTA,EMBARQ CLAUDIA ADRIAZOLA-STEIL,EMBARQ DARIO HIDALGO, EMBARQ LUIS ANTONIO LINDAU,EMBARQ PAULA MANOELA DOS SANTOS, EMBARQ EMAIL FOR CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] This is an abridged version of the paper presented at the conference. The full version is being submitted elsewhere. Details on the full paper can be obtained from the author. The Relationship between Safety, Capacity, and Operating Speed on Bus Rapid Transit DUDUTA, Nicolae; ADRIAZOLA-STEIL Claudia; HIDALGO, Dario; LINDAU, Luis Antonio; SANTOS, Paula Manoela; THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SAFETY, CAPACITY, AND OPERATING SPEED ON BUS RAPID TRANSIT CASE STUDY: TRANSOESTE BRT, RIO DE JANEIRO Nicolae Duduta1, Claudia Adriazola-Steil1, Dario Hidalgo1, Luis Antonio Lindau2, Paula Manoela dos Santos2 1: EMBARQ – the WRI Center for Sustainable Transport, 10 G St. NE Suite 800, Washington DC, 2: EMBARQ Brasil, Rua Luciana de Abreu, 471/801 90570-060 Porto Alegre/RS, Brazil Email for correspondence: [email protected] th 13 WCTR, 2013 – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1 The Relationship between Safety, Capacity, and Operating Speed on Bus Rapid Transit DUDUTA, Nicolae; ADRIAZOLA-STEIL Claudia; HIDALGO, Dario; LINDAU, Luis Antonio; SANTOS, Paula Manoela; ABSTRACT There is a growing body of research on the traffic safety aspects of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridors in Latin American cities. The findings suggest that some BRT design features – such as center lane configurations, left turn prohibitions, and signalized mid-block pedestrian crossings with refuge islands – can significantly improve safety on the corridors where BRTs operate. However, there is still a gap in knowledge about how the different safety features might impact the operational performance of the BRT. -

Comparison Between Bus Rapid Transit and Light-Rail Transit Systems: a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach

Urban Transport XXIII 143 COMPARISON BETWEEN BUS RAPID TRANSIT AND LIGHT-RAIL TRANSIT SYSTEMS: A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION ANALYSIS APPROACH MARÍA EUGENIA LÓPEZ LAMBAS1, NADIA GIUFFRIDA2, MATTEO IGNACCOLO2 & GIUSEPPE INTURRI2 1TRANSyT, Transport Research Centre, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain 2Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture (DICAR), University of Catania, Italy ABSTRACT The construction choice between two different transport systems in urban areas, as in the case of Light-Rail Transit (LRT) and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) solutions, is often performed on the basis of cost-benefit analysis and geometrical constraints due to the available space for the infrastructure. Classical economic analysis techniques are often unable to take into account some of the non-monetary parameters which have a huge impact on the final result of the choice, since they often include social acceptance and sustainability aspects. The application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) techniques can aid decision makers in the selection process, with the possibility to compare non-homogeneous criteria, both qualitative and quantitative, and allowing the generation of an objective ranking of the different alternatives. The coupling of MCDA and Geographic Information System (GIS) environments also permits an easier and faster analysis of spatial parameters, and a clearer representation of indicator comparisons. Based on these assumptions, a LRT and BRT system will be analysed according to their own transportation, economic, social and environmental impacts as a hypothetical exercise; moreover, through the use of MCDA techniques a global score for both systems will be determined, in order to allow for a fully comprehensive comparison. Keywords: BHLS, urban transport, transit systems, TOPSIS. -

Intercity Bus Program Section 5311 (F) Presented By: FTA Region 4 Staff Lorna Wilson, HQ Juan Morrison, HQ

Federal Transit Administration Intercity Bus Program Section 5311 (f) Presented by: FTA Region 4 Staff Lorna Wilson, HQ Juan Morrison, HQ Federal Transit Administration OBJECTIVE Support the connection between nonurbanized areas and the larger regional or national system of intercity bus service. Support services to meet the intercity travel needs of residents in nonurbanized areas. Support the infrastructure of the intercity bus network through planning and marketing assistance and capital investment in facilities. FTA encourages States to use the funding under 49 U.S.C. 5311(f) to support these national objectives, as well as priorities determined by the State. FTA TPM ver3.1 2 GOVERNOR’S CERTIFICATION A State is required to expend at least 15 percent of its apportionment for an intercity bus program, unless “the chief executive officer of the State certifies to the Secretary of Transportation, after consultation with affected intercity bus service providers, that the intercity bus service needs of the State are being met adequately.” FTA TPM ver3.1 3 INTERCITY BUS The legislative history indicates that the assessment of intercity bus needs be made “relative to other rural needs in the State.” A State certifying that its needs are adequately met must demonstrate that it has assessed statewide intercity mobility needs no more than four years before the date of the certification The State must document in the State Management Plan (SMP) its consultation process and any process that it develops for periodically assessing statewide -

Concord Coach (NH) O Dartmouth Coach (NH) O Peter Pan Bus Lines (MA)

KFH GROUP, INC. 2012 Vermont Public Transit Policy Plan INTERCITY BUS NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND POLICY OPTIONS White Paper January, 2012 Prepared for the: State of Vermont Agency of Transportation 4920 Elm Street, Suite 350 —Bethesda, MD 20814 —(301) 951-8660—FAX (301) 951-0026 Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Background and Policy Context......................................................................... 1-1 Policy Context...................................................................................................................... 1-1 Chapter 2: Inventory of Existing Intercity Passenger Services.......................................... 2-1 Intercity Bus......................................................................................................................... 2-1 Impacts of the Loss of Rural Intercity Bus Service......................................................... 2-8 Intercity Passenger Rail.................................................................................................... 2-11 Regional Transit Connections ......................................................................................... 2-11 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 2-13 Chapter 3: Analysis of Intercity Bus Service Needs............................................................ 3-1 Demographic Analysis of Intercity Bus Needs............................................................... 3-1 Public Input on Transit Needs ....................................................................................... -

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) New Jersey

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) for New Jersey By ORF 467 Transportation Systems Analysis, Fall 2004/05 Princeton University Prof. Alain L. Kornhauser Nkonye Okoh Mathe Y. Mosny Shawn Woodruff Rachel M. Blair Jeffery R Jones James H. Cong Jessica Blankshain Mike Daylamani Diana M. Zakem Darius A Craton Michael R Eber Matthew M Lauria Bradford Lyman M Martin-Easton Robert M Bauer Neset I Pirkul Megan L. Bernard Eugene Gokhvat Nike Lawrence Charles Wiggins Table of Contents: Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Personal Rapid Transit .......................................................................................... 3 New Jersey Coastline Summary .................................................................................................... 5 Burlington County (M. Mosney '06) ..............................................................................................6 Monmouth County (M. Bernard '06 & N. Pirkul '05) .....................................................................9 Hunterdon County (S. Woodruff GS .......................................................................................... 24 Mercer County (M. Martin-Easton '05) ........................................................................................31 Union County (B. Chu '05) ...........................................................................................................37 Cape May County (M. Eber '06) …...............................................................................................42 -

Part Ii a Personal Rapid Transit System

PART II A PERSONAL RAPID Author: Marcus Ekström TRANSIT SYSTEM 6. Introduction 6.1 Transportation and current 6.2 Problematization and study, design guidelines, and a detailed study on a PRT station at the waterfront. Within the work of action secondary question this thesis the design guidelines will be presented in this individual part, and the comprehensive and As much of today’s literature suggests, a shift in Visual encroachment in urban planning is vital detailed study will appear in our common proposal public transit is one of several needed actions to when discussing elevated architecture which comes for Cherry Beach. change people’s direct and indirect demand of with a Personal Rapid Transit system. These new oil. The shift has to be appealing to those who environments need to be designed with care both see today’s public transit as slow, non-reliable, for the users in terms of security and liveliness as 6.4 Assessment of sources in-convenient, and expensive, but none the least well as for the general public using the city and to those who see the car as the primary mode of the urban environment. It is also important how Finding materials to this study has not been transportation. Thus, a new transit system has these new transit solutions are introduced and if difficult but the problem with the sources is that to be quick, environmentally friendly, reliable, a suitable order can be identified to implement most of them come from the same groups and convenient, and cheap - hence what people demand them in different urban environments to gain as it is business for these companies that deal and the opposite of today’s public transit. -

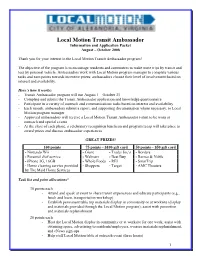

Local Motion Transit Ambassador Information and Application Packet August – October 2008

Local Motion Transit Ambassador Information and Application Packet August – October 2008 Thank you for your interest in the Local Motion Transit Ambassador program! The objective of the program is to encourage residents and commuters to make more trips by transit and less by personal vehicle. Ambassadors work with Local Motion program manager to complete various tasks and earn points towards incentive prizes; ambassadors choose their level of involvement based on interest and availability. Here’s how it works: - Transit Ambassador program will run August 1 – October 31 - Complete and submit the Transit Ambassador application and knowledge questionnaire - Participate in a variety of outreach and communications tasks based on interest and availability - Each month, ambassadors submit a report, and supporting documentation where necessary, to Local Motion program manager - Approved ambassadors will receive a Local Motion Transit Ambassador t-shirt to be worn at outreach and special events - At the close of each phase, a celebratory recognition luncheon and program recap will take place to award prizes and discuss ambassador experiences GREAT PRIZES! 100 points 75 points – $100 gift card 50 points – $50 gift card - Nintendo Wii - Giant - Trader Joe’s - Borders - Personal chef service - Walmart - Best Buy - Barnes & Noble - iPhone 3G, 16GB - Whole Foods - REI - SmarTrip - Home cleaning service provided - Shoppers - Target - AMC Theaters by The Maid Home Services Task list and point allocations* 30 points each - Attend and speak at event to -

Automated Guideway Transit: an Assessment of PRT and Other New

Chapter 1: Summary This report is a technology assessment of Automated Guideway Transit s stems, undertaken b The Office of Technology Assess- ment at t{ e request of the U.S. Seenate Committee on Appropriations, Transportation Subcommittee. Detailed findings are presented in Chapters 2 through 5. Major findings and conclusions are summarized in this chapter, which is organized as follows. The first section con- tains definitions and brief descriptions of Automated Guideway Transit systems. The definitions are followed by a summary of the major technical, economic, social, and institutional issues associated with Automated Guideway Transit. Next is a review of current R & D programs, with emphasis on those sponsored by the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA). 1n the last section, four options are outlined for research and development activities by UMTA in the coming fiscal year. D EFINITIONS Automated Guideway Transit (AGT) is a class of transportation systems in which unmanned vehicles are operated on fixed guideways along an exclusive right of way. The capacity of the vehic fes ranges from one or two up to 100 passengers. Siingle units or trains may be operated. Speeds are from 10 to +10 miles per hour. Headway (the time interval between vehicles moving along a main route) varies from one or two seconds to a minute. There may be a single route or branch- ing and interconnecting lines. This definition covers systems with a broad range of characteristics and includes many types of technology. To provide an organizing structure for the assessment, three major categories of AGT systems have been distinguished: Shuttle-Loop Transit (SLT).