The Threat from the Far Right in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lekarze Boją Się O Swoją Przyszłość W Wojewódzkim Szpitalu Szpitalu Specjalistycznym

DZIŚ n AKTUALNOŚCI str.1,3,7 n ROZMAITOŚCI str.6 n OGŁOSZENIA str.12 n MOTORYZACJA str.14 W NUMERZE: nZDROWIE str.4-5 n SZKOŁY str.8-11 nSPORT str.13 nREKLAMA str.2,15-16 ŻYCIEK POLECA: n Dworzec PKP wyburzony? str.3 n Pielęgniarka w szkolnym gabinecie? str.4 n Ubrania, które zagrażają zdrowiu dzieci str.5 CZĘSTOCHOWY n Co za ślub! Książę I POWIATU i aktoreczka str.6 www.zycieczestochowy.pl www.facebook.com/ZycieCzestochowyiPowiatu n Grabówka zabezpieczona Cena 1,20 zł Nr 58 (863) PIĄTEK-NIEDZIELA, 18-20 MAJA 2018 przed powodziami str.7 Nr ISSN 22 99 4440 (w tym 8% VAT) Częstochowa. Skłócona „Parkitka” Lekarze boją się o swoją przyszłość W Wojewódzkim Szpitalu Szpitalu Specjalistycznym. Za Specjalistycznym w Często- zgodą Urzędu Marszałkowskiego chowie dyrekcja „wymienia analizuje funkcjonowanie szpita- lekarzy”. – Tu się nie da pra- la. – Nie ujawnia się publicznie cować. Nasi lekarze są zastę- i bardzo dobrze zarabia, a doko- powani kadrą z Czeladzi i So- nuje zmian rękami obecnego dy- snowca, częstochowscy spe- rektora szpitala, z którym praco- cjaliści operują w woj. święto- wał kiedyś na Śląsku – denerwu- krzyskim i łódzkim, bo na Par- ją się lekarze. kitce nie ma dla nich miejsca Szpital na Parkitce w Często- – twierdzą zbulwersowani me- chowie jest jednym z najbardziej dycy z WSzS. – Ci ze Śląska zadłużonych w woj. śląskim. traktują szpital, jak własny W styczniu lekarze otrzymali folwark, a nas jak wyrobników 35-procentowe podwyżki. Staw- – dodają zirytowani. ka za godzinę dyżuru dla niektó- rych specjalistów wynosi 120 zł. Lekarze twierdzą, że są szyka- O sytuację w szpitalu zapytali- nowani, a doświadczona kadra śmy też szefową związku zawo- kierownicza zastępowana jest le- dowego lekarzy, Grażynę Kubat, karzami z krótkimi stażami spe- która odesłała nas do dyrektora cjalizacyjnymi. -

New Year's Eve Event Press Conference Material

This document contains information that will be released during today's press conference. Please refrain from releasing, posting any information online such as Twitter, Facebook, reports for media etc. New Year’s Eve event press conference material RIZIN FIGHTING WORLD GRAND-PRIX 2015 Committee Dear all media *** Please read below before covering press conference*** Thank you very much for covering our New Year’s Eve MMA event. Considering the venue’s policy and regulations, there are a few things that are needed to be followed. We appreciate your understanding and cooperation. - There limited amount of seats, so in case we run out of seats please cover the conference in the assigned area. We may ask you to change locations. - Filming of anything besides the press conference stage is prohibited (Including but not limited to Tokyo midtown area and other businesses). - Any media recording the conference besides the event host, must have identification listing your company, and individual’s name on them where the event staff can easily identify. - Please send any coverage of the conference on print or broadcasted, to the following address: - 3-2-1 Nishiazabu Hokushin Bld 7F, Minatoku, Tokyo Japan 106-0031 RIZIN FIGHTING WORLD GRAND-PRIX 2015 committee PR department Attn: Kimura For all media inquiries please contact RIZIN FIGHTING WORLD GRAND-PRIX 2015 Executive Committee PR Ryoko Kimura [email protected] RIZIN FIGHTING WORLD GRAND-PRIX 2015 1 Event Concept What do we seek in the future of fighting- . It is not to integrate all the existing fight promotions all over the world. It is to create a platform where each promotions and fighters can compete while they keep their diverse culture, customs and characteristics. -

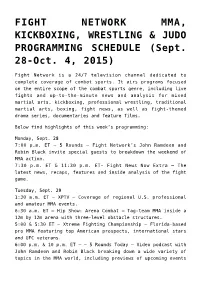

FIGHT NETWORK MMA, KICKBOXING, WRESTLING & JUDO PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE (Sept

FIGHT NETWORK MMA, KICKBOXING, WRESTLING & JUDO PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE (Sept. 28-Oct. 4, 2015) Fight Network is a 24/7 television channel dedicated to complete coverage of combat sports. It airs programs focused on the entire scope of the combat sports genre, including live fights and up-to-the-minute news and analysis for mixed martial arts, kickboxing, professional wrestling, traditional martial arts, boxing, fight news, as well as fight-themed drama series, documentaries and feature films. Below find highlights of this week’s programming: Monday, Sept. 28 7:00 p.m. ET – 5 Rounds – Fight Network’s John Ramdeen and Robin Black invite special guests to breakdown the weekend of MMA action. 7:30 p.m. ET & 11:30 p.m. ET- Fight News Now Extra – The latest news, recaps, features and inside analysis of the fight game. Tuesday, Sept. 29 1:30 a.m. ET – XPTV – Coverage of regional U.S. professional and amateur MMA events. 6:30 a.m. ET – Hip Show: Arena Combat – Tag-team MMA inside a 12m by 12m arena with three-level obstacle structures. 5:00 & 5:30 ET – Xtreme Fighting Championship – Florida-based pro MMA featuring top American prospects, international stars and UFC veterans. 6:00 p.m. & 10 p.m. ET — – 5 Rounds Today – Video podcast with John Ramdeen and Robin Black breaking down a wide variety of topics in the MMA world, including previews of upcoming events and all the latest rumors and headlines. 8:00 p.m. ET – 5 Rounds – Fight Network’s John Ramadeen and Robin Black invite special guests to breakdown the weekend of MMA action. -

Newsletter 01/2013

July 2013 NewsLithuania-Poland-Russia ENPI Cross-border Cooperation Programme 2007-2013 Inside the issue: JTS in action Contract signing speeding up European Cooperation Day 2012 celebrations 3rd Programme Annual Conference Olsztyn Branch Office opened and operating Trainings for Beneficiaries Art competition for children Getting to know Programme regions – Olsztyn Number of contracted projects grows week by week www.lt-pl-ru.eu Programme is co-financed by the European Union Photo: Lidzbark Warmiński, Poland News Lithuania-Poland-Russia ENPI Cross-border Cooperation Programme 2007-2013 JTS IN ACTION Małgorzata Woźniak, Head of the JTS: On behalf of the Joint Technical Secretariat I am very glad to welcome all the readers of the NEWS of Lithu- ania-Poland-Russia ENPI CBC Programme 2007-2013! Taking the opportunity I would like to introduce myself and the members of our team. Starting from myself, I would like to say that I had had 10 years of experience in project management before I was officially appointed to the Head of the JTS in December 2012. Since that time I have been coordinating the work of the JTS for successful Programme implementation. Together with my team we do our best to assist the Beneficiaries in all the issues concerning projects implementation, management and monitoring. As a matter of our daily work routine we provide consultations for the Beneficiaries, organize trainings, process and prepare documents necessary for smooth development of the Programme as well as every project. Besides, the JTS works in close and constant cooperation with the Programme’s main structures which are the Joint Managing Authority (represented by Ministry of Regional Development of the Republic of Poland) and Joint Monitoring Committee. -

Marketing Przyszłości Trendy

U N I W E R S Y T E T S Z C Z E C I Ń S K I ZESZYTY NAUKOWE NR 825 PROBLEMY ZARZĄDZANIA, FINANSÓW I MARKETINGU NR 36 MARKETING PRZYSZŁOŚCI TRENDY. STRATEGIE. INSTRUMENTY Zachowania konsumentów i komunikacja marketingowa w zmieniającym się otoczeniu SZCZECIN 2014 Rada Wydawnicza Adam Bechler, Tomasz Bernat, Anna Cedro, Paweł Ci ęszczyk, Piotr Michałowski, Małgorzata Ofiarska Aleksander Panasiuk, Grzegorz Wejman, Dariusz Wysocki, Renata Ziemi ńska Marek Górski – przewodnicz ący Rady Wydawniczej Edyta Łongiewska-Wijas – redaktor naczelna, dyrektor Wydawnictwa Naukowego Rada Naukowa Aurelia Bielawska – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Krystyna Brzozowska – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Eva Cudlinova – University of South Bohemia in České Bud ějovice, Czechy Wojciech Downar – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Wojciech Dro ŜdŜ – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Stanisław Flejterski – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Elena Horská – Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Słowacja Petra Jordanov – Fachhochschule Stralsund, Niemcy József Lehota – Szent Istvan University, W ęgry Krystyna Mazurek-Łopaci ńska – Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu José Antonio Ordaz Sanz – Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Hiszpania Józef Perenc – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński Gra Ŝyna Rosa – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński – przewodnicz ąca Rady Valentina Simkhovich – Bielarus State Economic University, Białoru ś Dagmar Škodová Parmová – University of South Bohemia in České Bud ějovice, Czechy Chrsitian Wey – Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Niemcy Rada Programowa Gra Ŝyna Rosa – Uniwersytet Szczeci ński – -

Arena Gliwice

SKUTECZNIE I TANIO JUŻ OD DOCIERAJ DO KAŻDEGO KLIENTA zł WlasnaGazeta.pl 0,15 NAJSKUTECZNIEJSZE NARZĘDZIE KAMPANII REKLAMOWYCH OFICJALNY BEZPŁATNY BIULETYN, NR 4 (22) / 2018 GALA KSW 46, 1 GRUDNIA 2018 R., AREna GLIWICE news SPONSOR WYDANIA PRAWIE 10 LAT NIE PRZEGRYWAŁEM I TE ZWYCIĘSTWA UŚPIŁY COŚ WE GALA KSW 46 MNIE. SZUKAŁEM W SOBIE TEGO PAZURA, ALE DOPIERO JAK ODKLEPAŁEM, SOBOTA, 1 GRUDNIA 2018R. POCZUŁEM, ŻE TO JEST TO, CZEGO MI BRAKOWAŁO. PRZEGRANA MOTYWUJE. AREna GLIWICE news 2 MAMED KHALIDOV www.kswmma.com WIELKI REWANŻ NA ŚLĄSKU FEDERACJA KSW PO RAZ CZWARTY ZAWITA NA GÓRNY ŚLĄSK Z NAJLEPSZYM WYDARZENIEM SPORTOWYM W TEJ CZĘŚCI EUROPY. PIĄTA I OSTANIA GALA KSW W 2018 ROKU – KSW 46 ODBĘDZIE SIĘ 1 GRUDNIA PO RAZ PIERWSZY W GLIWICACH, W OTWARTEJ W TYM ROKU NOWOCZESNEJ WIELOFUNKCYJNEJ HALI ARENA GLIWICE alką wieczoru sportów walki nad Wisłą, KSW, stanie do rewanżu z gali KSW 46 w Mamed Khalidov walczy dla Khalidovem po serii 6 wy- Arena Gliwice, KSW już ponad 10 lat i w 20 granych z rzędu przed cza- będzieW rewanżowy poje- starciach nikt nie potrafił sem. Dominator kategorii dynek pomiędzy mistrzem znaleźć na niego sposobu. półciężkiej wszystkie do- wagi półciężkiej, Tomaszem Dopiero w marcu tego roku tychczasowe boje kończył Narkunem, a legendą spor- po zaciętych trzech rundach nokautem lub poddaniem, z tów walki nad Wisłą, Mame- fenomenalnego pojedyn- czego aż dwanaście w pierw- dem Khalidovem. W drugim ku zawodnik Berkut Arra- szej rundzie. Wirtuoz parte- najważniejszym pojedynku chion Olsztyn musiał uznać ru na KSW 42 zwyciężył z mistrz kategorii lekkiej, Ma- wyższość Tomasza Narkuna Mamedem i zatrzymał jego teusz Gamrot będzie miał i odklepał ciasno zapięty passę 2918 dni bez porażki. -

Narkotyki, Lewy Tytoń, Broń Bez Zezwolenia

DZIŚ n AKTUALNOŚCI str. 1-2 n Z POLICYJNEGO n OGŁOSZENIA DROBNE str. 5-6 n SPORT str. 9 W NUMERZE: n WIEŚCI Z GMIN str. 3 NOTATNIKA str. 4 n MOTORYZACJA str. 7 n REKLAMA str. 8-9 CZĘSTOCHOWY I POWIATU www.zycieczestochowy.pl www.facebook.com/ZycieCzestochowyiPowiatu Cena 1,20 zł O sporcie czytaj na str. 8 Nr 59 (864) PONIEDZIAŁEK-WTOREK, 21-22 MAJA 2018 Nr ISSN 22 99 4440 (w tym 8% VAT) Częstochowa Narkotyki, lewy tytoń, broń bez zezwolenia W ręce częstochowskich policjantów wpadł 25-latek, podejrzany o posiada- nie sporej ilości narkotyków, w tym marihuany, metamfetaminy, tabletek ecstazy i amfetaminy. Mężczyzna zo- stał zatrzymany po policyjnym pości- gu. Do tego śledczy znaleźli u niego 5 krzaków konopi indyjskich, broń, bli- sko 20 kg „lewego” tytoniu i papiero- sy bez akcyzy. Decyzją sądu 25-latek trafił na najbliższe 3 miesiące do tym- czasowego aresztu. Kilka dni temu częstochowscy policjan- ci z referatu zajmującego się zwalczaniem przestępczości narkotykowej natrafili na trop 25-latka, który miał posiadać spore ilości narkotyków. Śledczy postanowili zatrzymać go do kontroli, gdy jechał swo- im autem. Mężczyzna nie reagował jed- nak na podawane mu sygnały dźwięko- we, ani świetlne podawane z policyjnego wozu. Kiedy drugi radiowóz zablokował mu drogę, a policjanci podbiegli do auta, okazało się, że 25-latek zabarykadował się w środku i chce odjechać. Aby go za- trzymać, stróże prawa musieli wybić szy- bę w samochodzie. Podczas przeszukania zajmowanych przez 25-latka posesji i mieszkania, śledczy znaleźli między innymi: przeszło 100 gramów marihuany, ponad 0,5 kg broń i kilka sztuk nabojów alarmowych. -

70 Ułatwień Dla Biznesu

DZIŚ n AKTUALNOŚCI str.1-6 n SZKOŁY str.8 n BUDOWNICTWO str.10 n OGŁOSZENIA str.12 W NUMERZE: nMOTORYZACJA str.7,13 n SPORT str.9,15 nDLAPRZEDSIĘBIORCÓWstr.11 nKULTURA str.14 CZĘSTOCHOWY I POWIATU www.zycieczestochowy.pl www.facebook.com/ZycieCzestochowyiPowiatu Cena 1,20 zł Nr 35 (994) PIĄTEK-NIEDZIELA, 22-24 MARCA 2019 Nr ISSN 22 99 4440 (w tym 8% VAT) Pakiet Przyjazne Prawo 70 ułatwień dla biznesu Wydłużenie terminu rozli- gał karze, jeżeli stwierdzone na- czenia VAT w imporcie, by ruszenie zostanie usunięte w wy- wzmocnić pozycję polskich znaczonym przez organ terminie. portów w konkurencji z zagra- MPiT przewiduje dwa ograni- nicznymi; prawo do błędu czenia: popełnianie naruszeń przez pierwszy rok działalno- po raz kolejny oraz przypadki ści dla mikro, małych i śred- rażącego naruszenia prawa nich przedsiębiorców; ochrona (ciężar wykazywany przez odpo- konsumencka, czyli m.in. pra- wiedni organ). wo do reklamacji, dla przedsię- Szacuje się, że propozycja mo- biorców zarejestrowanych że dotyczyć ok. 300 tys. przed- w CEIDG – to niektóre założe- siębiorców. Podobne rozwiąza- nia Pakietu Przyjazne Prawo nia funkcjonują we Francji i na (PPP). Przygotowany przez Mi- Litwie. nisterstwo Przedsiębiorczości i Technologii projekt trafił do Wydłużenie rozliczenia VAT uzgodnień, opiniowania i kon- w imporcie sultacji publicznych. Kolejna istotna zmiana to wy- dłużenie terminu rozliczenia Kluczowe rozwiązania PPP VAT w imporcie. Rozwiązanie to Pakiet Przyjazne Prawo to po- ma wzmocnić pozycję polskich nad 70 punktowych ułatwień portów w konkurencji z zagra- dla biznesu. Ma on charakter bowiem wyeliminować z systemu na przekonaniu, że większość wać przez rok od dnia podjęcia nicznymi. Propozycja ta polega przekrojowy - dotyka wielu róż- prawnego przepisy przestarzałe, naruszeń, które popełniają po- działalności gospodarczej po raz na odejściu od restrykcyjnego nych branż: od pocztowej, tele- uciążliwe, nieodpowiadające re- czątkujący przedsiębiorcy, nie pierwszy (albo ponownie po terminu płatności podatku VAT komunikacyjnej, lotniczej, ener- aliom społeczno-gospodarczym. -

Święto Częstochowskiej Młodzieży Częstochowscy Licealiści Jak Beteo, Bedeos I Solar

DZIŚ n AKTUALNOŚCI str. 1-2 n Z POLICYJNEGO n OGŁOSZENIA n MOTORYZACJA str. 6 W NUMERZE: n WIEŚCI Z GMIN str. 3 NOTATNIKA str. 4 DROBNE str. 5 n REKLAMA str. 7-8 CZĘSTOCHOWY I POWIATU www.zycieczestochowy.pl www.facebook.com/ZycieCzestochowyiPowiatu Cena 1,20 zł O sporcie czytaj w kolejnym numerze Życia… Nr 60 (865) ŚRODA-CZWARTEK, 23-24 MAJA 2018 Nr ISSN 22 99 4440 (w tym 8% VAT) 8 i 9 czerwca Święto częstochowskiej młodzieży Częstochowscy licealiści jak Beteo, Bedeos i Solar. Wszy- wzięli sprawy w swoje ręce scy to reprezentanci ekipy SB i organizują imprezę dedyko- Maffija Label. Beteo zasłynął ta- waną młodzieży szkolnej. - kimi kawałkami, jak „Love W naszym mieście są juwena- Show, czy „Nie wiesz nic”, Bede- lia i senioralia. Teraz – za os znany jest z utworów „Gang, sprawą drugiej edycji festiwa- gang, gang”, czy „Biały i mło- lu Summer Chill - do tej listy dy”, a Solar to twórca akcji „Hot dołączają... licealia – cieszą 16 Challenge”, która skupiła się młodzi częstochowianie. ponad 200 raperów. Wydarzenie, które otworzy te- Oprócz samej muzyki, na goroczny cykl imprez w Parku uczestników czekać będą też in- Wypoczynkowym Lisiniec, za- ne atrakcje, często ściśle nawią- planowano na 8 i 9 czerwca. zujące do „chillautowego” cha- rakteru imprezy – a często Podczas festiwalu czekać będą wręcz przeciwnie. Będą zatem zarówno koncerty muzyczne, jak m.in.: park adrenaliny, bitwa i szereg imprez towarzyszących, na balony z wodą, automaty do angażujących nie tylko młodzież, gier, rodeo, tory przeszkód, czy ale również całe rodziny. Będą wspólne oglądanie filmów na le- konkursy i zabawy, wspólne żakach. -

Mediaobrazovanie)

Media Education (Mediaobrazovanie). 2021. 17(2) Copyright © 2021 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Media Education (Mediaobrazovanie) Has been issued since 2005 ISSN 1994-4160 E-ISSN 2729-8132 2021. 17(2): 231-237 DOI: 10.13187/me.2021.2.231 www.ejournal53.com The Image of the Sportsman in Polish Sports Feature Films of the Second Decade of the 21st Century Piotr Drzewiecki a , * a Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, Poland Abstract The contemporary image of the sportsman can be studied not only in marketing terms, but also in film and media studies, indicating the protagonist's struggle with fate, his own weaknesses and limitations, as presented in the audiovisual message. The analysis focused on contemporary Polish feature films from 2011–2020, containing the story of athletes who experience both universal and national history and their own existential and moral dilemmas. The method used was the study of films and TV series as media messages and the theoretical perspective of an intimate approach to the analysis of the athlete's image. We may pose the following problematic questions: 1) what is the significance of universal and national history in the film and media presentation of the experiences of a given athlete? 2) in what way are his existential struggles symbolically captured in individual cinematic images? 3) what moral dilemmas does the athlete experience and how are they portrayed in a given audiovisual message? The analysed sports feature films portray sports rivalry less and focus the audience's attention more on the existential and moral choices of the protagonists. -

W Y J a Ś N I E N

news OFICJALNY bezpłATNY BIULETYN, NR 1/2012 GALA KSW 21, 1 GRUDNIA 2012 R., WARSZAWA, TORWAR OSTATECZNE WYJaśnienie KSW PO GONGU CałkOWICIE się wyłąCZAM, GALA 21 może TO JEST INSTYNKT, widzę SWOJEGO RYWALA, 1 GRUDNIA, 2012 TRZEBA się SKONCENTROWAć I WYGRAć Walkę WARSZAWA, TORWAR news 2 MAMED KHALIDOW www.konfrontacja.com ostateczne wyjaśnienie słOWO WSTępu uż w najbliższą so- mer jeden w europejskim UFC i M-1 Global, czarno- dzynarodowego Mistrza botę, 1 grudnia ko- rankingu MMA w wadze skóry Amerykanin Rodney KSW w wadze lekkiej. Jlejna gala z udziałem średniej, a od niedawna Wallace. współczesnych gladiato- aktor w kultowym serialu Oprócz tego zobaczymy rów. Włącz Polsat Sport od "M jak Miłość". Rywalem Oprócz dwóch walk wie- jeszcze pojedynki: Krzysztof 19:00 lub Polsat od 20:00 naturalizowanego Cze- czoru zobaczymy jeszcze Kułak kontra Piotr Strus, i śledź sportowe zmaga- czena będzie pogromca pięć walk ekstra, w tym Matt Horwich versus Terry nia w najbardziej realnym amerykańskich mistrzów dwie o mistrzowskie trofea. Martin i walkę pań pomię- sporcie walki. Gala KSW21 organizacji UFC, prawie O pas Międzynarodowego dzy Pauliną Bońkowską - Ostateczne wyjaśnienie, dwumetrowy zawodnik Mistrza KSW w wadze pół- i Karoliną Kowalkiewicz. tego nie możesz przegapić! lubiący walkę w stójce, średniej rękawice skrzy- Kendal "Da Spyder" Gro- żują ze sobą Aslambek Więcej informacji o zbliża- Właściciele Federacji ve. Saidov z klubu Arrachion jącej się gali KSW21 oraz KSW, Martin Lewandow- Olsztyn i Borys Mańkow- o wszystkich imprezach ski i Maciej Kawulski po Na tej samej gali do pierw- ski z Ankos Zapasy Po- Federacji KSW można prze- raz kolejny zadbali o naj- szej obrony pasa Mię- znań. -

Agora Group Management Discussion and Analysis for the Year 2019 to the Consolidated Financial Statements Translation Only

AGORA GROUP Management Discussion and Analysis for the year 2019 to the consolidated financial statements March 12, 2020 [www.agora.pl] Page 1 Agora Group Management Discussion and Analysis for the year 2019 to the consolidated financial statements translation only TABLE OF CONTENTS MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS (MD&A) FOR YEAR OF 2019 TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS.............. 5 I. IMPORTANT EVENTS AND FACTORS WHICH INFLUENCE THE FINANCIALS OF THE GROUP [1] ............................. 5 II. EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FACTORS IMPORTANT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GROUP .............................. 8 1. EXTERNAL FACTORS ........................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Advertising market [3] ..................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Copy sales of dailies [4] ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Cinema admissions [10] ............................................................................................................................... 9 2. INTERNAL FACTORS ......................................................................................................................................... 10 2.1. Revenue ...................................................................................................................................................