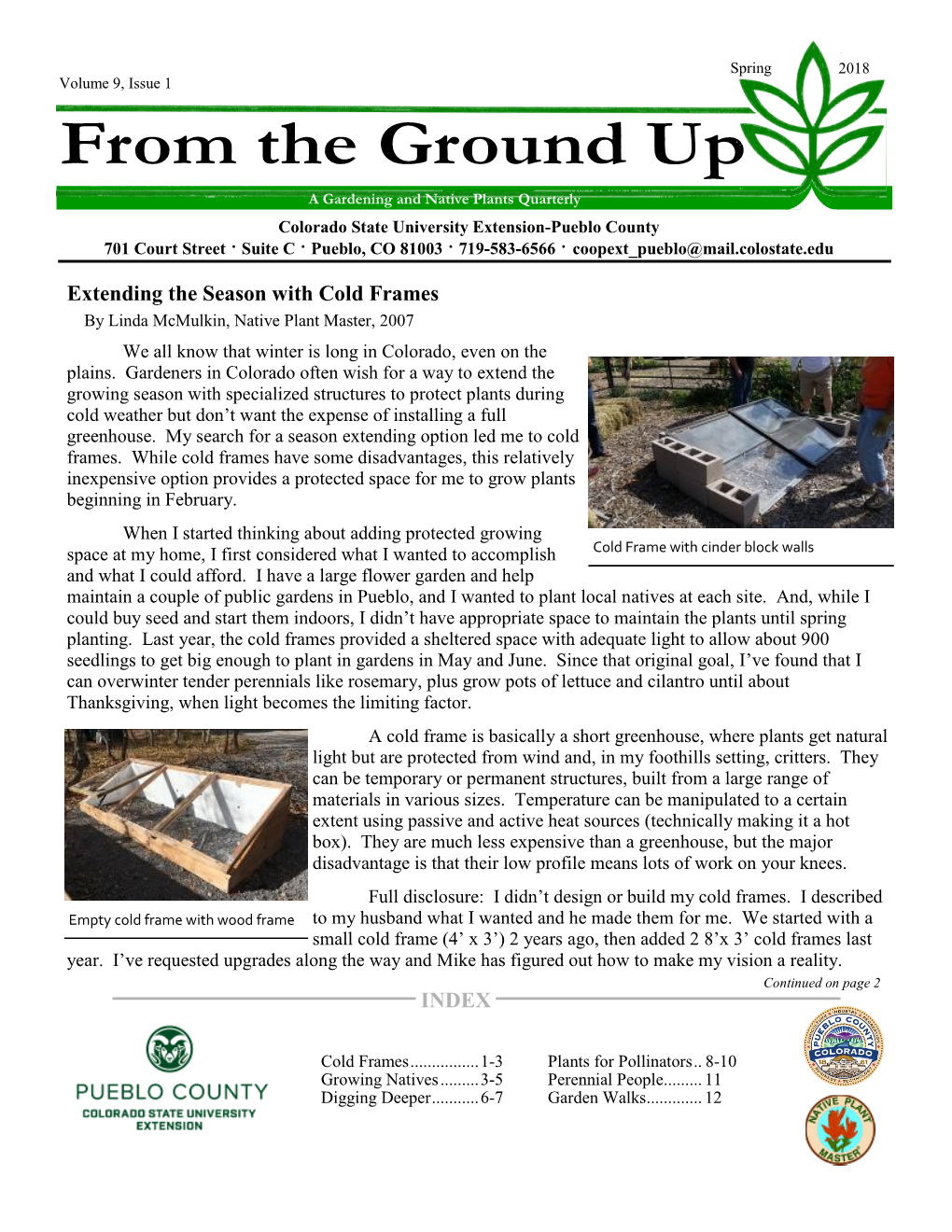

INDEX Extending the Season with Cold Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Tunnels

High Tunnels Using Low-Cost Technology to Increase Yields, Improve Quality and Extend the Season By Ted Blomgren and Tracy Frisch Produced by Regional Farm and Food Project and Cornell University with funding from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program Distributed by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture High Tunnels Authors Ted Blomgren Extension Associate, Cornell University Tracy Frisch Founder, Regional Farm and Food Project Contributing Author Steve Moore Farmer, Spring Grove, Pennsylvania Illustrations Naomi Litwin Published by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture May 2007 This publication is available on-line at www.uvm.edu/sustainableagriculture. Farmers highlighted in this publication can be viewed on the accompanying DVD. It is available from the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405. The cost per DVD (which includes shipping and handling) is $15 if mailed within the continental U.S. For other areas, please contact the Center at (802) 656-5459 or [email protected] with ordering questions. The High Tunnels project was made possible by a grant from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program (NE-SARE). Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, Vermont. University of Vermont Extension, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, cooperating, offer education and employment to everyone without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status. -

Rock Garden Quarterly

ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY VOLUME 55 NUMBER 2 SPRING 1997 COVER: Tulipa vvedevenskyi by Dick Van Reyper All Material Copyright © 1997 North American Rock Garden Society Printed by AgPress, 1531 Yuma Street, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY BULLETIN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY VOLUME 55 NUMBER 2 SPRING 1997 FEATURES Life with Bulbs in an Oregon Garden, by Molly Grothaus 83 Nuts about Bulbs in a Minor Way, by Andrew Osyany 87 Some Spring Crocuses, by John Grimshaw 93 Arisaema bockii: An Attenuata Mystery, by Guy Gusman 101 Arisaemas in the 1990s: An Update on a Modern Fashion, by Jim McClements 105 Spider Lilies, Hardy Native Amaryllids, by Don Hackenberry 109 Specialty Bulbs in the Holland Industry, by Brent and Becky Heath 117 From California to a Holland Bulb Grower, by W.H. de Goede 120 Kniphofia Notes, by Panayoti Kelaidis 123 The Useful Bulb Frame, by Jane McGary 131 Trillium Tricks: How to Germinate a Recalcitrant Seed, by John F. Gyer 137 DEPARTMENTS Seed Exchange 146 Book Reviews 148 82 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY VOL. 55(2) LIFE WITH BULBS IN AN OREGON GARDEN by Molly Grothaus Our garden is on the slope of an and a recording thermometer, I began extinct volcano, with an unobstructed, to discover how large the variation in full frontal view of Mt. Hood. We see warmth and light can be in an acre the side of Mt. Hood facing Portland, and a half of garden. with its top-to-bottom 'H' of south tilt• These investigations led to an inter• ed ridges. -

Hotbeds and Cold Frames for Montana Gardeners

Hotbeds and Cold Frames for Montana Gardeners by Ron Carlstrom, Gallatin County Extension Agent, Robert Gough, Professor of Horticulture, MSU, and Cheryl Moore-Gough, MSU Extension Horticulture Specialist, retired Growing vegetables and flowers from seeds can be challenging in Montana's short growing season, but a full-size greenhouse isn't necessary to extend your MontGuide season. MT199803AG Reviewed 3/11 THE USE OF COLD FRAMES AND hotbeds is an excellent way to 3' sash extend the Montana growing season, 3' providing a substitute for greenhouses. The gardener with limited space inside the home can use cold frames 2" x 4" stake 12" or hotbeds to start transplants from 2" x 4" cross tie seed. These simple structures also allow Montana gardeners to plant small vegetable crops earlier in the spring 8" soil and enjoy fresh vegetables later into 6" the fall. Cold frames are heated entirely manure 18" by the sun’s rays; hotbeds use the 6' sun’s rays and other sources of heat to maintain adequate temperatures. Consider the temperature and other climatic conditions of your location. When choosing between a cold frame FIGURE 1. A typical structure design and hotbed, consider the plants to be grown. Hardy plants such as cabbage need only simple, inexpensive facilities, but heat-loving plants such as peppers and eggplants qualities. The heartwoods from cedar and redwood provide should have more elaborate facilities for successful excellent rot resistance as does pressure-treated lumber. production in some of the colder areas of Montana. Pine, fir and spruce need to be treated to increase rot resistance. -

GREENHOUSE MANUAL an Introductory Guide for Educators

GREENHOUSE MANUAL An Introductory Guide for Educators UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN cityblossoms GREENHOUSE MANUAL An Introductory Guide for Educators A publication of the National Center for Appropriate Technology in collaboration with the United States Botanic Garden and City Blossoms UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN United States Botanic Garden (USBG) 100 Maryland Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20001 202.225.8333 | www.usbg.gov Mailing Address: 245 First Street, SW Washington, DC 20515 The U.S. Botanic Garden (USBG) is dedicated to demonstrating the aesthetic, cultural, economic, therapeutic, and ecological importance of plants to the well-being of humankind. The USBG fosters the exchange of ideas and information relevant to national and international partnerships. National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) 3040 Continental Drive, Butte, MT 59702 800.275.6228 | www.ncat.org The National Center for Appropriate Technology’s (NCAT) mission is to help people by championing small-scale, local, and sustainable solutions to reduce poverty, promote healthy communities, and protect natural resources. NCAT’s ATTRA Program is committed to providing high-value information and technical assistance to farmers, ranchers, Extension agents, educators, and others involved in sustainable agriculture in the United States. For more information on ATTRA and to access its publications, including this Greenhouse Manual: An Introductory Guide for Educators, visit www.attra.ncat.org or call the ATTRA toll-free hotline at 800.346.9140. cityblossoms City Blossoms is a nonprofit dedicated to fostering healthy communities by developing creative, kid-driven green spaces. Applying their unique brand of gardens, science, art, healthy living, and community building, they “blossom” in neighborhoods where kids, their families, and neighbors may not otherwise have access to green spaces. -

The Tennessee Vegetable Garden: Season Extension Methods

THE BACKYARD SERIES W 346-F BACKYARD VEGETABLES THE TENNESSEE VEGETABLE GARDEN SEASON EXTENSION METHODS Natalie Bumgarner, Assistant Professor and UT Extension Residential and Consumer Horticulture Specialist Department of Plant Sciences Vegetable production is increasingly of conditions — thus extending the popular for Tennessee residents. THE WHY AND growing season. Growing vegetables at home WHAT OF SEASON This practice of season extension allows provides financial and nutritional EXTENSION gardeners to have some control over benefits through the bounty of the environment around their crops a fresh harvest, and the activity (roots and/or shoots) to enhance One of the basic facts of gardening enhances personal health and productivity or maintain survival until is that crops will grow, develop and well-being. However, a basic conditions are more appropriate for produce when temperatures are growth. Certainly there are limits, but understanding of soils, site selection appropriate. Gardeners carefully plant adding an extra few days to weeks and crop maintenance is required cool- and warm-season crops to grow to the growing season can be quite before backyard growers can take during the time of year that targets useful in vegetable gardens. Methods full advantage of the benefits of their ideal temperature range. Managing are divided into two main groups: home food production. To meet crops according to surrounding management practices that can extend conditions can work very well and fit these needs, this series of fact growing periods and structures or the needs of many gardeners. However, sheets has been prepared by UT materials that can be used to alter gardeners have the option of altering Extension to inform home gardeners temperatures and extend seasons. -

Micro-Hardiness Agriculture Zones in the North Star Borough, Alaska: Past and Future Scenarios

Micro-hardiness Agriculture Zones in the North Star Borough, Alaska: Past and Future Scenarios Item Type Thesis Authors Hatch, Ellen W. Download date 03/10/2021 00:15:42 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/3187 Micro-hardiness Agriculture Zones in the North Star Borough, Alaska: Past and Future Scenarios A senior thesis presented to the faculty of the School of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks and The Senior Thesis Committee (N. Fresco, PhD, Advisor; M. Karlsson, PhD; V. Barber, PhD; R. Wheeler, PhD) towards the degree requirements of the Bachelor of Science in Natural Resources Management, Plant, Animal, Soil Science Option. by Ellen W. Hatch Fairbanks, Alaska May 2010 • ST 2011-02 agricultural & forestry experiment station 2 I. Abstract Table of Contents griculture in the Arctic is often limited by the low receipt Aof heat energy, which is often measured in growing degree I. Abstract days (GDD). With the advent of increasingly powerful climate II. Introduction modeling, projection and downscaling techniques, it is be- coming possible to examine future climates in high resolution. III. Literature Review, Part 1: Recent availability in Alaska has prompted interest in exam- Climate Modeling and Predictions ining the distribution of current and the potential future of Atmospheric Oceanic General Circulation Models local agriculture. The goal of this study was to utilize Scenarios Special Report Emission Scenarios A1B Network for Alaska Planning (SNAP) downscaled, ensemble Regional Climate Models projections to examine this in terms of GDDs in the Fairbanks Polar Region North Star Borough of Alaska. Historic and projected monthly Fairbanks North Star Borough, Alaska mean temperatures were utilized to calculate GDDs and then 2 Scenarios Network for Alaska Planning map the borough at a 4 km scale. -

Building a Cold Frame

Dear Extension Friends, December 2015 A huge thank you to everyone who participated in our online newsletter Inside this issue: survey last month! The information will be used for reporting purposes to demonstrate community impact, while the comments and suggestions you pro- ‘Carolina Sapphire’ 2 vided will help us to improve the newsletter for you—the reader. To those that Arizona Cypress made article suggestions, I will do my best to fulfill your Caring for requests—starting with this newsletter. From our 2 Houseplants Extension family to yours, please have a safe and happy holiday season! Building A Low Cost Vertical Tower for Best Regards, 3 Vegetables, Herbs, and Fruit Crops Alicia R. Lamborn Building A Cold 4 Horticulture Extension Agent Frame (continued) Baker County Extension Service Building A Cold Frame If you’re like me, then you have a lot of tropical plants that won’t tolerate cold winter temperatures and you probably prefer not to break your back hauling them in and out of the garage every time a hard freeze comes. If this is the case and you don’t own a greenhouse, build yourself a cold frame structure or temporary greenhouse to house your tender plants until spring. This structure will also work well for getting an early start on spring vegetable seed- lings, although you may need to modify the size to fit your needs. These instructions will help you build a basic structure that is a Quonset design, 3’ high x 6’ wide x 20’ long (similar to the photo shown above). This structure will require venting which can be done by opening the ends or rolling up one side of the plastic cover and then closing again later in the day. -

Cold Frames, High Tunnels, and Greenhouses: Choose a Growing Structure Best for You Stacy A

® ® University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Know how. Know now. G2246 Cold Frames, High Tunnels, and Greenhouses: Choose a Growing Structure Best for You Stacy A. Adams, Associate Professor of Practice Kim Todd, Extension Landscape Horticulture Specialist cooling equipment can be used throughout the year. Structure Cold frames, high tunnels, and greenhouses are differences include size and shape, construction materials used, growing structures that can be used to extend the grow- and installation method, and the way the interior temperature ing season for high value horticulture crops. is managed such as by opening vents or windows by hand or using automated heating and cooling systems. Before buying a growing structure, it is important to understand which type Several different types of growing structures are used in is most appropriate for your location and needs. the production of high value horticulture crops. These struc- tures extend the growing season by modifying the growing Cold Frames environment, and are used by gardeners, hobby farmers, and market growers. Cold frames are the smallest, simplest, and least expensive Growing structures create a protected environment for structures for protecting plants. Cold frames capture daytime producing vegetables, high value food crops, and flowering solar energy to heat the air space and soil floor or containers plants. The most commonly used structures are cold frames, instead of using electrical energy to heat the growing area. high tunnels, and greenhouses. These structures provide opti- The low structural design provides warmer nighttime air mum environmental conditions for early season production of temperatures around the plants by slowly releasing heat that plants or to allow crops to be harvested after fall frosts. -

Fall and Winter Vegetable Gardening in the Pacific Northwest

PNW 548 June 2001 Fall and Winter Vegetable Gardening in the Pacific Northwest Oregon State University + University of Idaho L Washington State University Fall and Winter Gardening in the Pacific Northwest P. Patterson ith a little extra planning and care, you can enjoy fresh vegetables from your garden most of the year. Many cool-season crops produce well in the fall and, in mild-winter W areas of the Pacific Northwest, hold through the winter if protected. You can plant these vegetables in mid- to late summer after you harvest spring crops and as space is available. To be successful, you need to plan ahead, choose varieties wisely, and give proper care to your plants. Keep in mind that fall and winter weather can vary greatly from year to year. A crop that fails one year due to an unusually early freeze or an abnormally cold winter might thrive in a milder year. Be willing to experiment, and don’t give up if your results some years are less than ideal. GETTING STARTED Choosing varieties all gardening is possible in most parts of the Pacific Northwest. Late plantings of warm- Fseason crops such as corn and beans can be harvested until the first killing frost. Cool-season crops, such as kale, turnips, mustard, broccoli, and cabbage, withstand frost and grow well during cool fall days. In fact, some of the best vegetables are produced during the warm days and cool nights of fall. These environmental conditions add sugar to sweet corn and crispness to carrots. Parsnips, kale, collards, Brussels sprouts, and Jerusalem artichokes are examples of crops that are improved by a touch of frost. -

A Garden for All Seasons

Issue # 178 - February/March 2000 Gardening on the back side of the calendar A Garden For By Eliot Coleman All Seasons Above: Barbara and Eliot's home greenhouse, where it all began. The couple has since turned their four-season harvest concept into a commercial enterprise, much to the delight of local restaurants and markets. Of late, these retailers have shown special interest in fresh carrots, tasty minutina and ready-to-eat radishes. Growing salad greens has been a labor of love for Eliot. Wild arugula (middle photo), along with beet leaves, endive and the occasional oak leaf and rouge d'Hiver lettuce, make for a swinging salad. Like most fresh homegrown vegetable enthusiasts, I have never wanted the garden to end. That doesn't mean I longed for an endless summer; I love the pleasures of fall, winter and spring. I just wanted year-round, freshly harvested food on the table. Somehow I always knew there had to be a simple way to combine cold-hardy crops with a little climatic protection during the colder times of the year. I am delighted to report that the results of 20 some years tinkering with this idea have proven me right. But first, some background on now it all came about. I was inspired to turn my winter gardening dream into reality back in 1981, when I took on the job of farm manager at a private .school in Vermont that grew most of its own food. In addition to rigorous academic studies, the school stressed practical experience on its farm as part and parcel of a student's education. -

Growing Your Own Vegetable Transplants

Growing Your Own Vegetable Transplants Small-farm and farmers-market growers may benefit from growing their own vegeta- ble transplants. On-farm production offers greater control of planting date and variety selection and reduces the risk of inadver- tently introducing pathogen spores or weed seeds on plants transported from other farms. Selling plants at the farmers market can pro- vide early-season revenue and diversify farm income, but it may not be suitable for all growers because of potential risks. Though not required, a greenhouse is useful for growing transplants. A four-season high tunnel, or hoop house, also works well as an unheated area for “hardening” transplants and as a growing space when heated. Common transplants include cucurbits (squash, cucumbers, and melons), solanaceous Figure 1. Cool-season vegetable transplants (lettuce, broccoli, cabbage) crops (tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants), propagated in a certified organic high tunnel. brassicas (broccoli, kale, and cabbage), as well as lettuces and strawberries. A small-scale vegetable seeds will remain viable for several years grower can be creative in designing a plant propaga- under proper conditions. (Onion seed is an exception tion system. This publication is for commercial and and loses viability in 1 to 2 years.) “hobby farm” growers who want to grow their own To remain dormant, seeds should be kept cold and vegetable transplants. dry and can be stored in the freezer. When handling Transplant Propagation Stages seed, count or weigh seed before storing to ensure leftover seeds stay dry and have been stored properly. Plants have different needs at different stages in Over time, vegetable seed loses viability and the ger- their development. -

Seed Starting & Transplanting

HGA-00032 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS Seed Starting & Transplanting The use of transplants enables the gardener to grow warm- Four Weeks in Individual Containers season vegetables to maturity outdoors, hasten maturity of Canary bird vine Tropaeolum peregrinum cool-season vegetables and achieve a longer bloom period Mignonette Reseda odorata for many annual flowers. Based on usual home tempera- *Nemophila Nemophila sp. tures (68° to 72°F) with at least 10 hours of daylight, the Sunflower Helianthus annus average number of weeks needed to grow transplants to the proper sizes are indicated below. Subtract the number VEGETABLES of weeks listed from the average date of the last spring frost Vegetable Weeks Remarks in your locality to determine planting dates. Less favorable Broccoli 4-6 growing conditions may require the longer period of time. Cabbage 4-6 FLOWERS Cauliflower 4-6 Celery 10-12 Slow growing. Flowers marked with an asterisk (*) do well in cooler Corn 2-4 temperatures of 50° to 55°F. Beginners will do well to try Cucumbers 3 Start two seeds in individual flowers from this group. containers; remove the weaker Six to Eight Weeks one after they germinate. Lettuce (head) 4-6 Start inside for early harvest. Butterfly flower Schizanthus Onions 8-10 English daisy Bellis perennis Feverfew Chrysanthemum parthenium Vegetable Weeks Remarks Lobelia Lobelia sp. Peppers 6-7 Nemesia Nemesia sp. Winter squash 3-4 Start two to three seeds in indi- Flowering tobacco Nicotiana sp. vidual containers and remove *Petunia Petunia hybrida the weaker one after they germi- *Snapdragon Antirrhinum majus nate.