A Garden for All Seasons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturday, February 14Th, 2008

Vermont Vegetable and Berry News – January 20, 2009 Compiled by Vern Grubinger, University of Vermont Extension (802) 257-7967 ext.13, [email protected] www.uvm.edu/vtvegandberry ANNUAL MEETING OF THE VERMONT VEGETABLE AND BERRY GROWERS ASSN. Feb. 9th, Capital Plaza Hotel, Montpelier. Pre-registrations must be received by Feb. 5. Details are on line at: www.uvm.edu/vtvegandberry click on „meetings and events‟ or call 802-257-7967. TECHNICAL WORKSHOPS FOR GROWERS AT NOFA-VT CONFERENCE ON FEB. 15 More conference info at: www.nofavt.org or call 802-434-4122 or e-mail [email protected] 9:15 - Worker Protection Safety Handler Certification Training. Anne MacMillan,Vermont Agency of Agriculture. Do you use organic pesticides on your farm? Have you been trained to meet the pesticide Worker Protection Standard? If not, this workshop will certify you and allow you to train your workers so your farm is in compliance with Vermont State Laws. 9:15 - Better Safe than Sorry: Addressing Food Safety Issues on Your Farm. Cheryl Wixson from Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners, Steve Gilman from NOFA-NY, and David Rogers from NOFA-VT. What practical, credible, and cost-effective steps might growers take to satisfy the food safety concerns of consumers, buyers, and regulators? How can growers evaluate food- safety “risks” in their operations? Regional efforts are examining these issues. MOFGA‟s ongoing work in developing new food-safety protocols (HAACP) for organic growers in Maine is a promising new approach for smaller-scale organic growers in the Northeast. 9:15 - Alternative Greenhouse Heating Systems. -

Year-Round Radicals (Pdf)

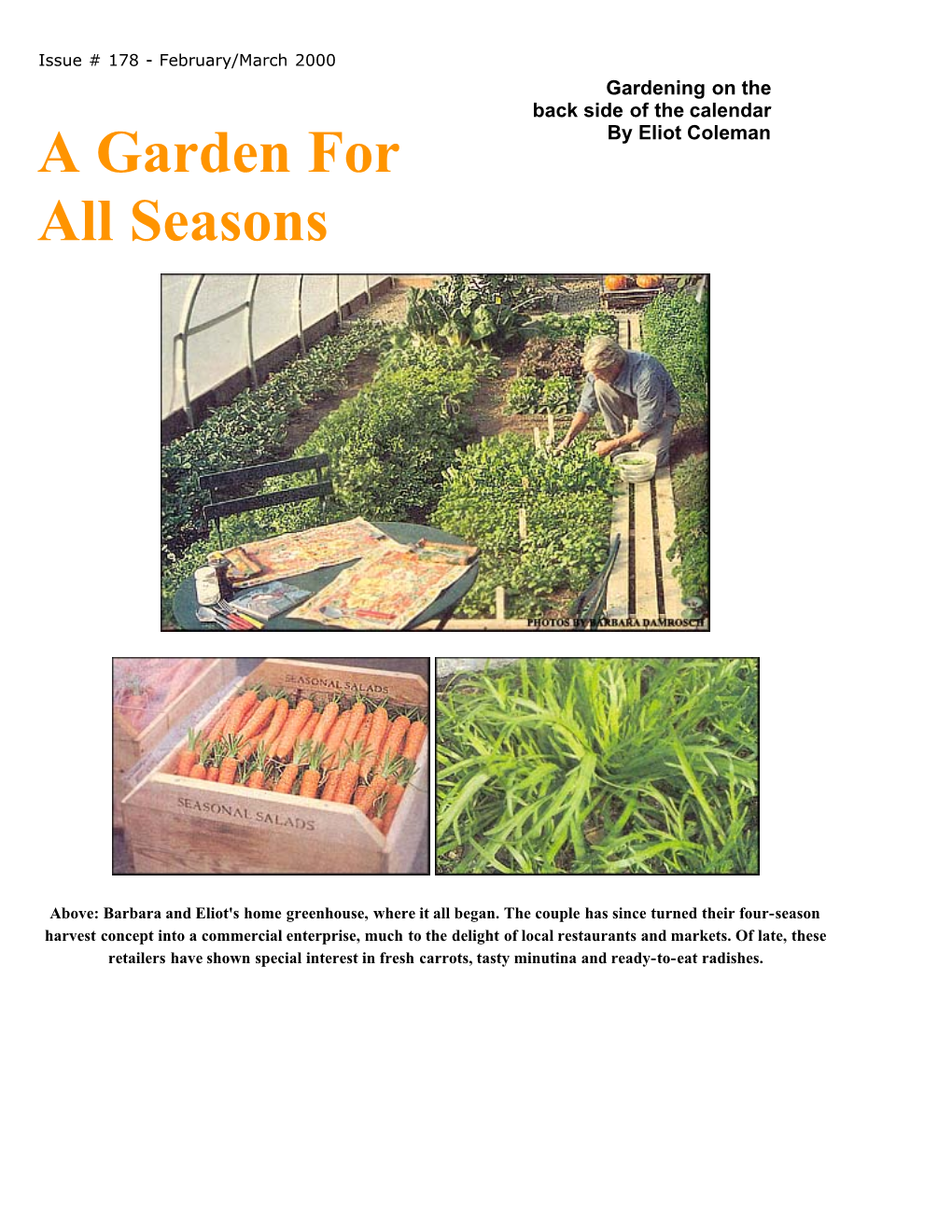

Year -round radicals A pair of practical farmers in the wilds of the Midcoast Profile eliot Coleman & Barbara Damrosch By Joshua Bodwell 60 Photography Darren Setlow 60 SEPTEMBER 07 MH+D “earth is so kind—just tickle her with a hoe -round and she laughs with a harvest.” Douglas Jerold radicals eir Cove Road wends and rolls along the water’s edge in Harborside. It is little more than a car-length wide, and for long stretches the dense evergreens on either Wside give the road a tunnel-like quality. Glimpses of Penobscot Bay appear through breaks in the tree line, and the air is ripe with the scent of salt. After a sharp bend, which is punctuated by a small swath of sandy beach, Weir Cove Road gives up its humble attempt at hot- top and turns to gravel. Before long, the forest opens to fi elds, rows of plastic-covered hoop-style greenhouses, and a large round sign that proclaims, FOUR SEASON FARM . It’s down this far end of the winding road, in a place well off the beaten path, that organic- gardening gurus Eliot Coleman and Barbara Damrosch have been creating their own version of the good life. At Four Season Farm—which is, as the name implies, a year- round farm—there is an acre and a half of land under cultivation, one-quarter acre of which is covered by greenhouses. That seemingly diminutive acre and a half, however, yields enough produce to supply fi ve to ten restaurants in the region (depending on the time of year), two markets (the Blue Hill Co-op and the Bucks Harbor Market), and an on-site farm stand. -

Winter Gardening DECEMBER • Remove Annuals No Longer Producing

Clallam County Gardening Calendar Winter Gardening DECEMBER • Remove annuals no longer producing. Clean up empty beds. • Drain and coil hoses; empty and stack cages; and clean garden containers. • Rake fallen apple and pear leaves to protect against scab. Do not compost infected leaves. • Test garden soil. For instructions contact Clallam Conservation District (www.clallamcd.org). Based on results, apply lime or sulfur to adjust pH. Do not add other amendments at this time. • After the first hard frost, add mulch around winter vegetables, strawberry plants, and root crops being stored in the ground. • Clean, repair, and sharpen garden tools. JANUARY • Prune fruit trees and established blueberries while dormant. Do not prune during freezing weather. • If aphids and mites have been a past problem, apply horticultural oil to fruit trees and blueberry bushes. Do not apply when plants are wet, temps are below 40°, or rain is likely in the next 24 hrs. • Plan vegetable garden rotation; order seeds. • Consider building raised beds for easier gardening. FEBRUARY • Prune fruit trees and established blueberries while dormant. Do not prune in freezing weather. • Thin second -year raspberry canes to 3 to 5 canes per square foot. Remove dead or damaged canes. • Start cool-weather vegetables from seed indoors. • Sow salad greens under cover for harvest in March. • Mow or chop cover crops before they set seed. Allow leaves and stems to dry and dig in, if soil is dry enough to be worked. Vegetables typically harvested in the winter on the North Olympic Peninsula: Overwintered Crops • Arugula • Kale • Beets • Leeks • Brussels sprouts • Green onions • Carrots • Parsley • Chard • Parsnips • Evergreen herbs • Spinach For interesting wintertime reading, see WSU’s resources for sustainable home gardening at http://gardening.wsu.edu/ Plant Clinics Closed for the Season Submit gardening and plant questions to: Plant Clinic Helpline: (360) 417-2514 Email: [email protected] 2/14/2020. -

Your Winter Vegetable Garden the Second Act Mike Kluk, Nevada County Master Gardener

Your Winter Vegetable Garden The Second Act Mike Kluk, Nevada County Master Gardener For many of us, when the curtain protection. A well-hydrated plant candidates. Instead of winter cover of frost falls on our summer will handle the cold better than crops or straw on all of your beds, vegetables, we put away our one that is drought stressed. So, some will be growing salad and a tools and wait for spring to begin be prepared to water if there is an vegetable side dish. If you live in again. But it is possible to have a extended dry spell in the winter. snow country, you will probably second act with a whole new cast Choosing beds that are protected need to use a season-extender of characters. Growing a winter from the prevailing winter wind will structure. You will also need to clear garden is a great way to continue also help. the snow away to allow enough to enjoy fresh, healthy vegetables I have managed to have a light to reach the plants. The throughout the year. With a bit of respectable winter garden for exception would be root crops such planning and a few winter-specific several years. Our nighttime as beets and carrots. If you plant a approaches, you can successfully temperatures on clear nights sufficient number in the spring, you grow vegetables that are as varied are generally in the low 20s can enjoy them all winter. Unless and tasty as anything summer has with excursions into the teens your soil freezes, mature beets and to offer. -

Seattle Tilth Summer Classes and Camps

summer 2016 classes & camps get all the dirt! seattletilth.org learn Map Page 2 About Seattle Tilth page 3 Veggie Gardening page 4 Urban Livestock page 5 Kitchen page 6 Permaculture & Sustainable Landscapes page 7 Summer Garden & Farm Camps page 8 Garden Educator Workshops page 9 Kids & Youth page 10 Registration Form page 11 Classes by Date page 12 21 ACRES FARM Seattle Tilth’s McAULIFFE PARK Upcoming JOIN US! SEATTLE TILTH SEATTLE OFFICE, GOOD YOUTH Events SHEPHERD CENTER GARDEN GARDEN WORKS Chicken Coop & Urban Farm Tour, Saturday, July 16 Throughout Seattle Harvest Fair, Saturday, August 6 Seattle Meridian Park seattletilth.org BRADNER GARDENS PARK Visit us RAINIER BEACH LEARNING at our GARDEN RAINIER BEACH URBAN FARM gardens & AND WETLANDS farms! community learning garden educational farm volunteer opportunity classes for adults Auburn SEATTLE TILTH children’s garden programs FARM WORKS summer youth camp Learning Gardens & Class Locations Bradner Gardens Park (BGP) Rainier Beach Learning Garden (RBLG) Seattle Tilth Farm Works 1730 Bradner Place S, Seattle 4800 S Henderson, Seattle 17601 SE Lake Moneysmith Rd, Auburn Good Shepherd Center (GSC) Rainier Beach Urban Farm & Seattle Youth Garden Works 4649 Sunnyside Ave N, Seattle Wetlands (RBUFW) At the Center for Urban Horticulture 5513 S Cloverdale St, Seattle 3501 NE 41st St, Seattle McAuliffe Park (MP) 10824 NE 116th St, Kirkland 2 About Seattle Tilth Seattle Tilth, Tilth Producers and Cascade Harvest Coalition have merged! Our mission is to build an ecologically sound, economically viable and socially equitable food system. Our education programs focus on the entire food system: earth, farm garden, market and kitchen. -

High Tunnels

High Tunnels Using Low-Cost Technology to Increase Yields, Improve Quality and Extend the Season By Ted Blomgren and Tracy Frisch Produced by Regional Farm and Food Project and Cornell University with funding from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program Distributed by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture High Tunnels Authors Ted Blomgren Extension Associate, Cornell University Tracy Frisch Founder, Regional Farm and Food Project Contributing Author Steve Moore Farmer, Spring Grove, Pennsylvania Illustrations Naomi Litwin Published by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture May 2007 This publication is available on-line at www.uvm.edu/sustainableagriculture. Farmers highlighted in this publication can be viewed on the accompanying DVD. It is available from the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405. The cost per DVD (which includes shipping and handling) is $15 if mailed within the continental U.S. For other areas, please contact the Center at (802) 656-5459 or [email protected] with ordering questions. The High Tunnels project was made possible by a grant from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program (NE-SARE). Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, Vermont. University of Vermont Extension, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, cooperating, offer education and employment to everyone without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status. -

VEGETABLES in the WINTER GARDEN Jacqueline Champa, Placer County Master Gardener

VEGETABLES IN THE WINTER GARDEN Jacqueline Champa, Placer County Master Gardener From The Curious Gardener, Summer 2008 Have you thought of having a winter vegetable garden? We are fortunate to live in Northern California where we are able to grow a number of great vegetables during the shortened, wet, cold days of winter. A good pick for the winter garden might be a cold hardy green vegetable such as brussel sprouts, broccoli, or asparagus. Root crops such as carrots, beets, leek, or carrots grow successfully too. Cool season greens are perfect for winter gardening. Kale, spinach, Swiss Chard, leaf lettuce, and exotics like mache, mizuna, and tatsoi are fun to grow. In fact, there are varieties of these greens specially suited to frosty temperatures. The first step to putting together a winter garden is to know what to grow in your geographic area. Placer and Nevada Counties are unique, covering a wide range of climatic conditions and elevations including rain and snow, wind, mild to freezing temperature and varying soil types from rocky to loamy bottomland. There is a wide range of vegetables that can be grown locally and it can be a daunting task just to pick out what you want to grow! To help out, Old Farmer’s Almanac offers an on-line Garden Guide that can be customized for your geographic location (by zip code or city). Simply go to the website (www.almanac.com/gardening) and look for the Outdoor Planting Table for 2009. After you change the geographic location to where you live (zip code or town, state)— Voila! a planting table of the crops that will flourish in your growing area is created. -

Rock Garden Quarterly

ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY VOLUME 55 NUMBER 2 SPRING 1997 COVER: Tulipa vvedevenskyi by Dick Van Reyper All Material Copyright © 1997 North American Rock Garden Society Printed by AgPress, 1531 Yuma Street, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY BULLETIN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN ROCK GARDEN SOCIETY VOLUME 55 NUMBER 2 SPRING 1997 FEATURES Life with Bulbs in an Oregon Garden, by Molly Grothaus 83 Nuts about Bulbs in a Minor Way, by Andrew Osyany 87 Some Spring Crocuses, by John Grimshaw 93 Arisaema bockii: An Attenuata Mystery, by Guy Gusman 101 Arisaemas in the 1990s: An Update on a Modern Fashion, by Jim McClements 105 Spider Lilies, Hardy Native Amaryllids, by Don Hackenberry 109 Specialty Bulbs in the Holland Industry, by Brent and Becky Heath 117 From California to a Holland Bulb Grower, by W.H. de Goede 120 Kniphofia Notes, by Panayoti Kelaidis 123 The Useful Bulb Frame, by Jane McGary 131 Trillium Tricks: How to Germinate a Recalcitrant Seed, by John F. Gyer 137 DEPARTMENTS Seed Exchange 146 Book Reviews 148 82 ROCK GARDEN QUARTERLY VOL. 55(2) LIFE WITH BULBS IN AN OREGON GARDEN by Molly Grothaus Our garden is on the slope of an and a recording thermometer, I began extinct volcano, with an unobstructed, to discover how large the variation in full frontal view of Mt. Hood. We see warmth and light can be in an acre the side of Mt. Hood facing Portland, and a half of garden. with its top-to-bottom 'H' of south tilt• These investigations led to an inter• ed ridges. -

Hotbeds and Cold Frames for Montana Gardeners

Hotbeds and Cold Frames for Montana Gardeners by Ron Carlstrom, Gallatin County Extension Agent, Robert Gough, Professor of Horticulture, MSU, and Cheryl Moore-Gough, MSU Extension Horticulture Specialist, retired Growing vegetables and flowers from seeds can be challenging in Montana's short growing season, but a full-size greenhouse isn't necessary to extend your MontGuide season. MT199803AG Reviewed 3/11 THE USE OF COLD FRAMES AND hotbeds is an excellent way to 3' sash extend the Montana growing season, 3' providing a substitute for greenhouses. The gardener with limited space inside the home can use cold frames 2" x 4" stake 12" or hotbeds to start transplants from 2" x 4" cross tie seed. These simple structures also allow Montana gardeners to plant small vegetable crops earlier in the spring 8" soil and enjoy fresh vegetables later into 6" the fall. Cold frames are heated entirely manure 18" by the sun’s rays; hotbeds use the 6' sun’s rays and other sources of heat to maintain adequate temperatures. Consider the temperature and other climatic conditions of your location. When choosing between a cold frame FIGURE 1. A typical structure design and hotbed, consider the plants to be grown. Hardy plants such as cabbage need only simple, inexpensive facilities, but heat-loving plants such as peppers and eggplants qualities. The heartwoods from cedar and redwood provide should have more elaborate facilities for successful excellent rot resistance as does pressure-treated lumber. production in some of the colder areas of Montana. Pine, fir and spruce need to be treated to increase rot resistance. -

Perennials for Winter Gardens Perennials for Winter Gardens

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety November / December 2010 Perennials for Winter Gardens Edible Landscaping for Small Spaces A New Perspective on Garden Cleanup Outstanding Conifers contents Volume 89, Number 6 . November / December 2010 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS Boston’s garden contest grows to record size, 2011 AHS President’s Council trip planned for Houston, Gala highlights, rave reviews for Armitage webinar in October, author of article for The American Gardener receives garden-writing award, new butterfly-themed children’s garden installed at River Farm. 12 2010 AMERICA IN BLOOM AWARD WINNERS Twelve cities are recognized for their community beautification efforts. 42 ONE ON ONE WITH… David Karp: Fruit detective. page 26 44 HOMEGROWN HARVEST The pleasures of popcorn. EDIBLE LANDSCAPING FOR SMALL SPACES 46 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK 14 Replacing pavement with plants in San BY ROSALIND CREASY Francisco, soil bacterium may boost cognitive With some know-how, you can grow all sorts of vegetables, fruits, function, study finds fewer plant species on and herbs in small spaces. earth now than before, a fungus-and-virus combination may cause honeybee colony collapse disorder, USDA funds school garden CAREFREE MOSS BY CAROLE OTTESEN 20 program, Park Seed sold, Rudbeckia Denver Looking for an attractive substitute for grass in a shady spot? Try Daisy™ wins grand prize in American moss; it’ll grow on you. Garden Award Contest. 50 GREEN GARAGE® OUTSTANDING CONIFERS BY RITA PELCZAR 26 A miscellany of useful garden helpers. This group of trees and shrubs is beautiful year round, but shines brightest in winter. -

GREENHOUSE MANUAL an Introductory Guide for Educators

GREENHOUSE MANUAL An Introductory Guide for Educators UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN cityblossoms GREENHOUSE MANUAL An Introductory Guide for Educators A publication of the National Center for Appropriate Technology in collaboration with the United States Botanic Garden and City Blossoms UNITED STATES BOTANIC GARDEN United States Botanic Garden (USBG) 100 Maryland Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20001 202.225.8333 | www.usbg.gov Mailing Address: 245 First Street, SW Washington, DC 20515 The U.S. Botanic Garden (USBG) is dedicated to demonstrating the aesthetic, cultural, economic, therapeutic, and ecological importance of plants to the well-being of humankind. The USBG fosters the exchange of ideas and information relevant to national and international partnerships. National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) 3040 Continental Drive, Butte, MT 59702 800.275.6228 | www.ncat.org The National Center for Appropriate Technology’s (NCAT) mission is to help people by championing small-scale, local, and sustainable solutions to reduce poverty, promote healthy communities, and protect natural resources. NCAT’s ATTRA Program is committed to providing high-value information and technical assistance to farmers, ranchers, Extension agents, educators, and others involved in sustainable agriculture in the United States. For more information on ATTRA and to access its publications, including this Greenhouse Manual: An Introductory Guide for Educators, visit www.attra.ncat.org or call the ATTRA toll-free hotline at 800.346.9140. cityblossoms City Blossoms is a nonprofit dedicated to fostering healthy communities by developing creative, kid-driven green spaces. Applying their unique brand of gardens, science, art, healthy living, and community building, they “blossom” in neighborhoods where kids, their families, and neighbors may not otherwise have access to green spaces. -

Lush & Efficient

R EVISED E DITION LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley Coachella Valley Water District LLushush && EEfficientfficient LandscapeLandscape GardeningGardening inin thethe CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley RR EVISEDEVISED EE DITIONDITION CoachellaCoachella ValleyValley WaterWater DistrictDistrict IRONWOOD PRESS Tucson, Arizona Coachella Valley Cover photo by Acknowledgements A special thank you goes to Water District Scott Millard Directors and staff of the Ann Copeland, now retired Coachella Valley Water District, Primary photography by Coachella Valley Water District from CVWD. An educational specialist who taught water CVWD, is a local govern- Scott Millard: © pages 5, 7, 8, 9, extend their gratitude to Scott ment agency controlled by Millard of Ironwood Press science to the children of five directors elected by the 10 (right), 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, Coachella Valley, she took on 20, 21, 22 (left), 23, 24, 25, 26, in Tucson, Ariz., for bringing registered voters within its this revised book to fruition. the additional responsibility 1,000 square mile service area. 27, 28, 35, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 of working closely with Eric That area in the southeastern (top & lower right), 46 (top left, Scott and primary author Eric A. Johnson were partners at Johnson, reading his text and California desert extends from bottom center & bottom right), identifying photos to illustrate west of Palm Springs to the 47 (bottom left inset, bottom Ironwood Press and published communities along the Salton several excellent desert land- it. She also worked closely right & upper right), 48 (left & with contributing author Dave Sea. It is located primarily in upper left), 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, scaping books together before Riverside County but extends Harbison in developing and 55 (left & center inset & right), Eric’s death.