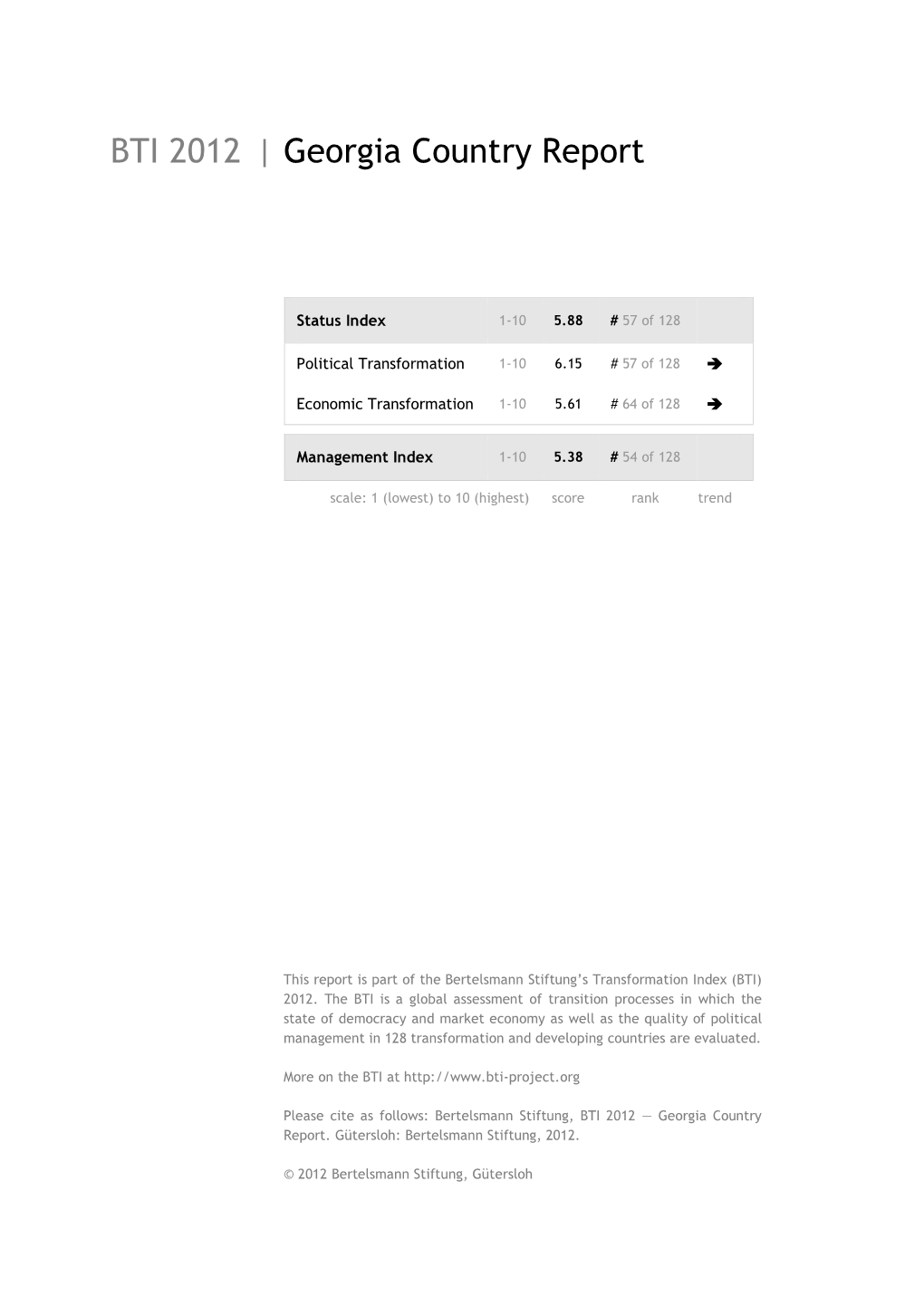

BTI 2012 | Georgia Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report

THE GOLD STANDARD IN ROYALTY INVESTMENTS 2018 — Annual Report Corporate & Shareholder Information Stock Exchange Listings Board of Directors Toronto Stock Exchange Andrew T. Swarthout TSX: SSL David Awram David E. De Witt New York Stock Exchange John P. A. Budreski NYSE.AMERICAN: SAND Mary L. Little Nolan Watson Vera Kobalia Transfer Agent Computershare Investor Services 2nd Floor, 510 Burrard Street Corporate Offices Vancouver, British Columbia Vancouver Head Office V6C 3B9 Suite 1400, 400 Burrard Street T 604 661 9400 Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 3A6 T 604 689 0234 Corporate Secretary F 604 689 7317 Christine Gregory [email protected] www.sandstormgold.com Auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP Toronto Office PricewaterhouseCoopers Place Suite 1110, 8 King Street Suite 1400, 250 Howe Street Toronto, Ontario Vancouver, British Columbia M5C 1B5 V6C 3S7 T 416 238 1152 T 604 806 7000 F 604 806 7806 Sandstorm is a gold royalty company with a portfolio of over 185 royalties. Since 2008, we’ve been a leader in reshaping the mine investment landscape with our innovative royalty model. But that’s just the beginning. From five royalties in 2010, Sandstorm has experienced significant growth within a short time. In fact, compared to other gold investment companies, we have one of the industry’s best growth profiles. Within the next few years, our royalty production is projected to increase more than 100%. And we’re not planning on slowing down. With new acquisitions underway and more to come, we are focused on diversifying and growing our -

Liam O'shea Phd Thesis

POLICE REFORM AND STATE-BUILDING IN GEORGIA, KYRGYZSTAN AND RUSSIA Liam O’Shea A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/5165 This item is protected by original copyright POLICE REFORM AND STATE-BUILDING IN GEORGIA, KYRGYZSTAN AND RUSSIA Liam O’Shea This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University oF St Andrews Date of Submission – 24th January 2014 1. Candidate’s declarations: I Liam O'Shea hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 83,500 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in October 2008 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD International Relations in November 2009; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2008 and 2014. Date …… signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD International Relations in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

The Report Energy Projects and Corruption in Georgia

ENERGY PROJECTS AND CORRUPTION IN GEORGIA Green Alternative, 2013 The report has been prepared by Green Alternative with the support of Open Society Georgia Foundation within the framework of the coalition project Detection of Cases of Elite Corruption and Governmental Pressure on Business. Partner organizations in the coalition project are: Economic Policy Research Centre, Green Alternative, Transparency International Georgia and Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association. The opinions expressed in the present publication represent the position of Green Alternative and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Open Society Georgia Foundation or partner organizations. Author: Kety Gujaraidze Green Alternative, 2013 Contents Introduc on ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 1. Peri – Company Profi le ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Peri Ltd .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Companies, in which Peri Ltd owns shares .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Companies affi liated to Peri Ltd .................................................................................................................................................. -

No. 20: Religion in the South Caucasus

No. 20 11 October 2010 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh resourcesecurityinstitute.org www.laender-analysen.de www.res.ethz.ch www.boell.ge RELIGION IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS ■■Religiosity in Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan 2 By Robia Charles, Tbilisi ■■GRAPHS Religiosity in the South Caucasus in Opinion Polls 5 ■■The Role of the Armenian Church During Military Conflicts 7 By Harutyun Harutyunyan, Yerevan ■■Canonization, Obedience, and Defiance: Strategies for Survival of the Orthodox Communities in Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia 10 By Kimitaka Matsuzato, Hokkaido ■■Ethnic Georgian Muslims: A Comparison of Highland and Lowland Villages 13 By Ruslan Baramidze, Tbilisi ■■CHRONICLE From 4 July to 3 October 2010 16 Resource Research Centre Center German Association for HEINRICH BÖLL STIFTUNG Security for East European Studies for Security Studies East European Studies SOUTH CAUCASUS Institute University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 20, 11 October 2010 2 Religiosity in Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan By Robia Charles, Tbilisi Abstract This article examines the nature of religiosity in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. Annual nationwide sur- vey data results from the Caucasus Barometer (CB) in 2008 and 2007 show that religious practice as mea- sured by service attendance, fasting and prayer are low throughout the region, similar to levels found in Western Europe. However, religious affiliation, the importance of religion in one’s daily life and trust in religious institutions is high in all three countries. This provides support for understanding religiosity as a multidimensional concept. Little Practice, But Strong Affiliation until 1985. The results of perestroika in the religious This article examines religiosity among populations in sphere under Gorbachev were a body of state-religion Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. -

Euro-Atlantic Discourse in Georgia from the Rose Revolution to the Defeat of the United National Movement

FACULTEIT POLITIEKE EN SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN INSTRUMENTALISING EURO-ATLANTICISM EURO-ATLANTIC DISCOURSE IN GEORGIA FROM THE ROSE REVOLUTION TO THE DEFEAT OF THE UNITED NATIONAL MOVEMENT Frederik Coene 6 December 2013 A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Political Sciences Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Rik Coolsaet Co-supervisors: Prof. Dr. Bruno De Cordier and Dr. Oliver Reisner FOREWORD Pursuing a doctoral programme is both an academic and a personal challenge. When a student embarks on this long and ambitious adventure, he is not aware of the numerous hindrances and delightful moments that will cross his path in the following years. Also I have experienced a mosaic of emotions and stumbled over many obstacles during my journey, but I have been fortunate to be surrounded by a large number of great colleagues and friends. Without their support, I might not have brought this to a successful end. Two people have unconditionally supported me for the past thirty five years. My parents have done anything they could to provide me with a good education and to provide me with all opportunities to develop myself. I may not always have understood or appreciated their intentions, but without them I would not have been able to reach my humble achievements. I want to thank my supervisors Prof. Dr. Rik Coolsaet, Prof. Dr. Bruno De Cordier and Dr. Oliver Reisner for their guidance and advice during the research and writing of this dissertation. A large number of people helped to collect data and information, brought new insights during fascinating discussions, and provided their feedback on early drafts of the dissertation. -

FICHA PAÍS Georgia Georgia

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Georgia Georgia La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios, no defendiendo posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. ABRIL 2021 Religión: Iglesia ortodoxa georgiana (83,9%). Alrededor de un 2% perte- Georgia necen a la Iglesia ortodoxa rusa; el 3,9% pertenecen a la Iglesia apostólica armenia, siendo en su mayoría étnicamente armenios. Alrededor de un 9,9% de la población es musulmana, principalmente en la República Autónoma de Adjara (Ayaria) con una amplia minoría en Tbilisi. Los católicos son aproxi- madamente el 0,8% de la población y se encuentran en el sur de Georgia y Tbilisi. Existe una comunidad judía en Tbilisi que cuenta con dos sinagogas. Forma de Estado: República (no usado en la denominación oficial). RUSIA División administrativa: 9 regiones: Guria, Imereti, Kakheti, Kvemo Kartli, Sukhumi Mtskheta-Mtianeti, Racha-Lechkhumi y Kvemo Svaneti, Samegrelo y Zemo Svaneti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, Shida Kartli; 1 ciudad: Tbilisi; 2 repúblicas Zugdidi Ambrdauri autónomas: Abjasia (centro administrativo Sujumi) y Adjara (centro admi- Kutaisi nistrativo Batumi). Número de residentes españoles: 42 (2021). Mar Negro Gori Uzurgeti Telavi TBILISI Batumi Akhaltsikhe Rustavi 1.2. Geografía País ribereño del Mar Negro. Situado al sur de la cordillera del Cáucaso es un TURQUÍA ARMENIA país montañoso (macizo caucásico en el norte y sur del país). -

Georgia Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Georgia Country Report Status Index 1-10 6.16 # 48 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 6.50 # 52 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 5.82 # 57 of 129 Management Index 1-10 5.76 # 41 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Georgia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Georgia 2 Key Indicators Population M 4.5 HDI 0.745 GDP p.c. $ 5901.5 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.6 HDI rank of 187 72 Gini Index 42.1 Life expectancy years 73.8 UN Education Index 0.842 Poverty3 % 35.6 Urban population % 53.0 Gender inequality2 0.438 Aid per capita $ 111.3 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The most important event in the period under review was undoubtedly the October 2012 parliamentary elections. During the 22 years of Georgia’s transformation process, change of power has been provoked variously by putsches, demonstrations or impeachments. -

18437034Ledforumagen

Organized by: Organized by: Hosted by: Supported by: Partners: Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia The EU Committee of the Regions Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia European Commission – DG DEVCO Ministry of Finance of Georgia Foundation for Effective Governance Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure of Georgia Ministry for Parliamentary Affairs, Afghanistan Committee on European Integration of the Parliament of Georgia Ministry of Territorial Administration of Armenia Regional Policy, Self Government and Mountainous Regions Committee of the KfW Parliament of Georgia City of Berlin Nantes Métropole Arab Town Organization Aslan Global Brighton & Hove City Council City of Odessa Airport Regions Conference Ernst & Young City of Cairo City of Paris Union of Architects of Georgia fDi Magazine City of Fingal City of Prachatice Union of Baltic Cities Fitch Ratings City of Gdynia City of Riga CEMR Fundación Metrópoli City of Juba City of Rustavi Energy Cities Location Connections City of Kharkiv City of Saarbrücken Communities Finance Officers Association of Armenia Think City Kharkiv, Province City of Sumgait Communities Association of Armenia Cisco City of Kiev Tel Aviv Yafo Municipality NALA Georgia Delta Comm City of Lodz City of Turku NALAS HUAWEI City of Lublin City of Vienna IWA, Georgia ORACLE City of Ludwigshafen City of Vilnius UITP, MENA IBM City of Munich Wielkopolska Region DWVG, Georgia Free University City of Nairobi City of Yerevan Agricultural University Of Georgia Tbilisi State University Center for Training an Consultancy of Georgia Media Partners: Sponsors: Welcome I am delighted to welcome all of the Like many other cities Tbilisi is participants to the 6th International growing while at the same time setting Local Economic Development Forum ambitious objectives for becoming a to be held in Tbilisi on the 25th – 26th more livable city and generating of April, 2012. -

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2010

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2010 January 5 January 2010 Georgia launches a Russian-language Caucasus television channel 8 January 2010 Georgian Airways conducts its first Tbilisi-Moscow charter flight 14 January 2010 Russian Deputy Interior Minister Arkady Yedelev says that terrorist groups are being trained at military bases in Georgia to launch attacks on the territory of the Russian Federation 14 January 2010 Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov urges progress in the Turkish- Armenian rapprochement 19 January 2010 Armenian opposition journalist Nikol Pashinian is sentenced to seven years in jail on charges of organizing mass unrest following the presidential elections of 2008 19 January 2010 Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze meets with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Iranian Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki in Tehran 19 January 2010 Georgian Prime Minister Nika Gilauri visits Egypt 19 January 2010 The European Commission includes Azerbaijan on the list of countries that can export black caviar to the European Union 20 January 2010 Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan says that an Armenian court’s reference to the mass killings of Armenians during World War I as “genocide” could harm the Armenian-Turkish rapprochement process 20 January 2010 Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili meets with Estonian President Thomas Hendrik Ilves in Tallinn, Estonia 20 January 2010 Former Armenian President Robert Kocharian meets with Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadinejad and Iran Foreign Minister Manuchehr Mottaki -

What to Do in Georgia This Summer

GEORGIA’S NEW CHACHA COCKTAILS GEORGIAN LARI BONDS PENSION REFORM Investor.geA Magazine Of The American Chamber Of Commerce In Georgia ISSUE 63 JUN-JULY 2018 What to Do in Georgia this Summer JUNE-JULY 2018 Investor.ge | 3 Investor.ge CONTENT 6 Investment News 8 Innovators and Disruptors: Ideas To Bring Change 10 The Best Minds in the Business: Famous Economists Weigh In On Georgia 12 Big Georgian Brands Look to Lari Bonds for Expansion 22 14 Explainer: Georgia’s New Pension System 16 Fake Cement is a Problem in Georgia: How to Spot Counterfeits 18 Tbilisi Overhauling Master Plan, Tackling Traffic 20 Georgia Plans Recycling Programs to Tackle Growing Waste 22 Tbilisi’s Night Economy: A New Mayor and a New Plan to Boost Jobs 24 SUMMER FUN: A Cultural Calendar of Events, Performances, Exhibitions and Festivals in 32 Georgia 32 SWOT: Georgia’s Tourism and Hospitality Sector 36 In Numbers: Georgia’s Growing Tourism Sector 38 Chacha Stars in Tbilisi’s Growing Cocktail Culture 40 Georgia Celebrates the Centenary of the Georgian Democratic Republic 44 NEWS ...... 44 4 | Investor.ge JUNE-JULY 2018 ! "# $ " % ! & '$ ( ! JUNE-JULYJUNE-JULY 20182018 Investor.geInvestor.ge | 5 and more inclusive growth by fostering The factory, MGMtex, will produce INVESTMENT private investment, productivity, and clothing for H&M stores and is projected competitiveness.” to employ as many as 400 people. There are currently 130 people working GEORGIA, EUROPEAN FREE at the factory, which was built with a Geor- NEWS TRADE ASSOCIATION SIGN DEAL gian-Romanian investment of 7 million lari The Georgian government and the (about $2.81 million), the report said. -

Promoting Idps' and Women's Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia

Promoting IDPs’ and Women’s Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia Columbia University Women’s Political Resource Center M a y 2 0 1 2 Promoting IDPs’ and Women’s Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia May 2012 Authors: Alexandra dos Reis Drilon Gashi Samantha Hammer Marissa Polnerow Alejandro Roche del Fraille Janine White Completed in fulfillment of the Workshop in Development Practice at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, Spring 2012. In partnership with the Women’s Political Resource Center, Tbilisi, Georgia. Cover images (clockwise): Newly constructed IDP housing in Potskho-Etseri; Old-wave IDP women focus group in Tbilisi; New-wave IDP men focus group in Karaleti IDP settlement. Cover image sources: Keti Terdzishvili, CARE International, and Alejandro Roche del Fraille Other photos: Alejandro Roche del Fraille Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs 420 West 118th St New York, NY 10027 www.sipa.columbia.edu View of Tbilisi, Marissa Polnerow 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful for the support of our client organization, the Women’s Political Resource Center (WPRC), and WPRC’s President, Lika Nadaraia, who has extended this unique opportunity to our team. We would also like to thank the supportive staff members of WPRC, including Keti Bakradze, and Nanuka Mzhavanadze. We hope that our project will contribute to the valuable work undertaken at WPRC, and its newly-launched Frontline Center in Tbilisi. At Columbia University, we were privileged to work with Professor Gocha Lordkipanidze, our academic advisor, who shared with us a wealth of insight and guidance. His knowledge on Georgian society, governance, international law, human rights, and conflict resolution helped advance our research and inform this report. -

From the Cinderella of Soviet Modernization

FROM THE CINDERELLA OF SOVIET MODERNIZATION TO THE POST- SOVIET RETURN TO “NATIONAL TRADITIONS”: WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN AZERBAIJAN, ARMENIA, AND GEORGIA Nona Shahnazaryan, Edita Badasyan, Gunel Movlud Caucasus Edition – Journal of Conflict Transformation 2016 This paper discusses in a comparative perspective the issues of women’s political participation in the countries of the South Caucasus focusing both on differences and common trends of policies toward women in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. The analysis of the Soviet heritage in the area of women’s emancipation allows tracking the “logic” of post-Soviet transformations without fragmenting the post-Soviet experiences and pulling them out of context. This approach exposes which processes of the modern period are rooted in the Soviet past and which have fundamentally new sources. Attention is focused on the changes in the system of earmarked spaces for women (i.e. the quota system) and the discourses that are formed around this topic. The paper exposes perspectives impeding female leadership, and, on the contrary, promoting women’s political participation and involvement in the public sphere. The paper also deciphers what discursive or verbal, non-verbal, and other strategies women use in politics in order to be accepted professionally. 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Women’s political rights and representation in the Soviet