Passages Through Time and Space: in Memory of Chantal Akerman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue-2018 Web W Covers.Pdf

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE 22 years in Hollywood… The COLCOA French Film this year. The French NeWave 2.0 lineup on Saturday is Festival has become a reference for many and a composed of first films written and directed by women. landmark with a non-stop growing popularity year after The Focus on a Filmmaker day will be offered to writer, year. This longevity has several reasons: the continued director, actor Mélanie Laurent and one of our panels will support of its creator, the Franco-American Cultural address the role of women in the French film industry. Fund (a unique partnership between DGA, MPA, SACEM and WGA West); the faithfulness of our audience and The future is also about new talent highlighted at sponsors; the interest of professionals (American and the festival. A large number of filmmakers invited to French filmmakers, distributors, producers, agents, COLCOA this year are newcomers. The popular compe- journalists); our unique location – the Directors Guild of tition dedicated to short films is back with a record 23 America in Hollywood – and, of course, the involvement films selected, and first films represent a significant part of a dedicated team. of the cinema selection. As in 2017, you will also be able to discover the work of new talent through our Television, Now, because of the continuing digital (r)evolution in Digital Series and Virtual Reality selections. the film and television series industry, the life of a film or series depends on people who spread the word and The future is, ultimately, about a new generation of foreign create a buzz. -

Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema Between Malick and Von Trier

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 24 Issue 2 October 2020 Article 9 October 2020 Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema between Malick and von Trier Pablo Alzola Rey Juan Carlos University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Alzola, Pablo (2020) "Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema between Malick and von Trier," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 24 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. DOI: 10.32873/uno.dc.jrf.24.2.009 Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol24/iss2/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema between Malick and von Trier Abstract This is a book review of John Caruana and Mark Cauchi, eds., Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema between Malick and von Trier. Author Notes Pablo Alzola is Assistant Professor of Esthetics at the Department of Educational Sciences, Language, Culture and Arts at Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC) in Madrid, Spain. He has written several articles and book chapters on film and eligion,r together with a recent book on the cinema of Terrence Malick: El cine de Terrence Malick. La esperanza de llegar a casa (EUNSA, 2020). This book review is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol24/iss2/9 Alzola: Immanent Frames Caruana, John and Cauchi, Mark (eds.). Immanent Frames: Postsecular Cinema between Malick and von Trier. -

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 Janvier – 2 Mars 2018

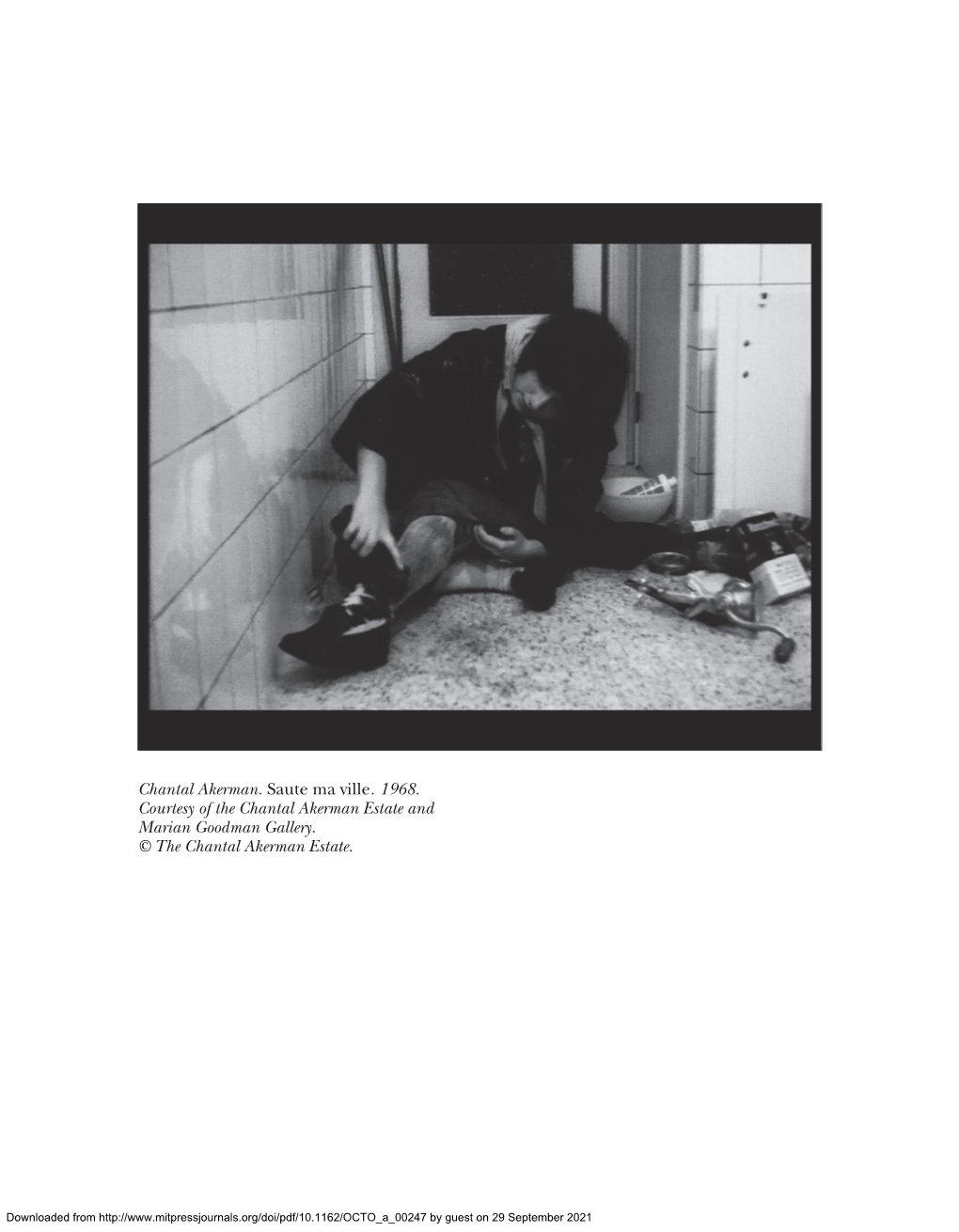

Rétrospective Chantal Akerman 31 janvier – 2 mars 2018 AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE WALLONIE-BRUXELLES INTERNATIONAL ET LE CONCOURS DU CENTRE WALLONIE BRUXELLES Héritière à la fois de la Nouvelle Vague et du cinéma underground américain, l’œuvre de Chantal Akerman explore avec élégance les notions de frontière et de transmission. Ses films vont de l’essai expérimental (Hotel Monterey), aux récits de la solitude (Jeanne Dielman), en passant par des comédies à l’humour triste (Un divan à New York) et les somptueuses adaptations de classiques littéraires (Proust pour La Captive). CONFÉRENCE et DIALOGUES “CHANTAL AKERMAN : L’ESPACE PENDANT UN CERTAIN TEMPS” PAR JÉRÔME MOMCILOVIC je 01 fév 19h Chantal Akerman a dit souvent son étonnement face à cette formule banale, qui nous vient parfois pour exprimer le plaisir pris un film : ne pas voir le temps passer. De l’appartement du premier film (Saute ma ville, 1968) a celui du dernier (No Home Movie, 2015), des rues traversées par la fiction (Toute une nuit) a celles longées par le documentaire (D’Est), ses films ont suivi une morale rigoureusement inverse : regarder le temps, pour mieux voir l’espace, et nous le faire habiter ainsi en compagnie de tous les fantômes qui le hantent. A la suite de la conférence, à 21h30, projection d’un film choisi par le conférencier : News from Home. Jerome Momcilovic est critique de cinema, responsable des pages cinéma du magazine Chronic’art. Il est l’auteur chez Capricci de Prodiges d’Arnold Schwarzenegger (2016) et, en février 2018, d’un essai sur le cinema de Chantal Akerman Dieu se reposa, mais pas nous. -

Belgium and Brussels

BELGIUM AND BRUSSELS Independent since 1830, Belgium is a constitutional and a half from the French capital. Which brings us to and parliamentarian monarchy, whose current king is yet another benefit of being in Brussels: it is just a short Philipp the 1st. Belgium is a federal state consisting hop away from Paris, London, and Amsterdam… of three regions: Brussels, the bilingual capital where French and Dutch are official languages; Flanders, the Dutch-speaking North; and Wallonia, the FOR MORE INFORMATION Frenchspeaking - and Germanspeaking South. ABOUT BRUSSELS, Among the famous Belgians, one can think of the famous composers and singers Jacques Brel and you can visit the official Brussels website Stromae; the actors Benoît Poelvoorde and Matthias https://visit.brussels/en Schoenaerts; the writers Amélie Nothomb and Maurice Maeterlinck (Nobel Prize for Literature in 1911); the artists and cartoonists Georges Rémi (Hergé, Father of Tintin), Franquin (Gaston Lagaffe), Peyo (the Smurfs), Morris (Lucky Luke); the film directors Chantal Akerman, Jaco Van Dormael, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne; the painter René Magritte; the architect Victor Horta; and the athletes Eddy Merckx (cyclist), Eden Hazard (football) and Nafissatou Thiam (athletics). Belgium wouldn’t be Belgium without its mouth- watering chocolates, its wide range of local beers and mussels served with French fries ! Belgium has a lot of historical, artistic, gastronomical, architectural and natural wonders which we invite you to discover during your stay here. BRUXELLES, LE SAVIEZ- MA BELLE VOUS ? Brussels is among the world’s most diverse capitals, Our university has a long standing home to the headquarters of the European Union, tradition of excellence, as evidenced by NATO, and countless international companies and the many accolades given in recognition organisations. -

Presseheft English.Indd

„Das Boot Ist Voll“ („The Boat is Full“ 1981) by Markus Imhoof “The Boat is Full” – AWARDS CONTENTS: - Film Festival Berlin: Silver Bear (best script and best direction of actors), 1981 Short Summary / Summary 2 - Price of the International Film Press Organisation (FIPRESCI), 1981 A Short History of the Hitler refugees in Switzerland 3 - Price of the International Committee for the Distribution of Arts and The Reception History of „The Boat is Full“ 5 Literature by Film, 1981 History, Restoration and Reconstruction 8 - Price of the International Catholic Film Offi ce, 1981 Memoriav 10 Cast/ Team/ Technical Specifi cations 12 - Otto Dibelus Award: Price of the International Protestant Film Jury, 1981 Biographies: - Quality Premium of the Swiss Department for Internal Affairs, 1981 Markus Imhoof 13 - Film Price of the City of Zürich, 1981 Tina Engel 14 - Price of the Foundation ALIZA (remembering the victims of the attempt of Curt Boir October 3 in 1980, Copernic street), 1981 Renate Steiger - Big Price of the 10th Human Rights Festival in Strassburg, 1981 Mathias Gnädinger 15 George Reinhart - Festival of Historical Films: Golden Eagle, 1981 Awards 16 - Price of the Evangelical Jury, Berlin, 1981 - Price René Clair – David di Donatello, Rom, 1982 - David Wark Griffi th Award (National Council of Film Critics in New York), 1982 - New York: Cristopher Award for direction and script, 1982 - Nomination for an Academy Award for the best foreign fi lm, 1982 Press pictures at : www.markus-imhoof.ch (data-fi le in tif-format) 16 1 SHORT SUMMARY MATHIAS GNÄDINGER GEORGE REINHART (1942–1997) A hotchpotch group of refugees secretly manages to cross the border into Switzerland Born 1941 in Ramsen. -

Bilan 2011 Du Centre Du Cinéma Et De L

PRODUCTION, PROMOTION ET DIFFUSION CINÉMATOGRAPHIQUES ET AUDIOVISUELLES LE BILAN 2011 Sommaire Introduction 5 Introduction générale 7 Faits marquants 8 Enveloppe budgétaire pour la production audiovisuelle 2011 12 Chapitre 1 Commission de Sélection des Films 15 Budget 17 Faits marquants 17 Répartition des promesses d’aides 22 Sélection des projets 23 Récapitulatif des sélections de 2008 à 2011 24 Projets soutenus 27 Tableau comparatif des liquidations de 2008 à 2011 (CSF) 48 Productions aidées par la CSF, terminées en 2011 49 Chapitre 2 Subventions à la diffusion et primes à la qualité 53 Subventions à la diffusion et primes à la qualité 55 Films reconnus par la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles en 2011 56 Montants des subventions à la diffusion et primes à la qualité 60 Chapitre 3 Coproductions avec les éditeurs et les distributeurs de services télévisuels 69 Contribution des télévisions et des distributeurs à la production 71 Convention entre la RTBF, les associations professionnelles et la FWB 75 Tableau comparatif des liquidations de 2008 à 2011 (Fonds Spécial) 79 Coproductions et préachats des éditeurs et distributeurs privés 80 Chapitre 4 Ateliers d’accueil, de production et ateliers d’écoles 85 Subventions octroyées par le Centre du Cinéma et de l’Audiovisuel 87 Bilan 91 Chapitre 5 Promotion et diffusion 105 Promotion et diffusion 107 Publications - Informations 115 Prix de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles 120 Chapitre 6 Aides européennes, coproduction et relations internationales 123 Aides européennes 125 Coproduction internationale -

Chantal Akerman a Family in Brusse Thursday-Saturday

( \ Chantal Akerman A Family in Brussels Thursday-Saturday, October 11-13, 2001 6:30 pm Sunday, October 14, 2001 5 pm ( ( Dia center for the arts 545 west 22nd street new york selected general bibliography, alphabetical Renowned filmmaker Chantal Akerman presents A Family in Brussels (1998), a stream-of-consciousness text, laced with autobiographical refer Aubenas, Jacqueline, ed. Chantal Akerman . Cahier no. 1. Brussels: Ateliers ences, which encompasses multiple subjectivities. This is the first English des Arts, 1 982 . language production of this work, which Akerman wrote and performed as Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson a monologue in Paris and Brussels. and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989. lshaghpour, Youssef. Cinema Contemporain: De ce cote du miroir. Paris: Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels, Belgium, in 1950. In the early Editions de la Difference, 1986. 1970s, when she was living in New York, she encountered the experimental Kuhn, Annette. Women's Pictures : Feminism and Cinema. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982 . cinema of Jonas Mekas, Michael Snow, and Andy Warhol. Employing similar Margulies, Ivonne. Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman's Hyperrealist approaches-with lingering shots, minimal dialogue, deserted spaces, and Everyday. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996. symmetry-her films explore such themes as the passage of time and ritual Mayne, Judith. The Woman at the Keyhole: Feminism and Woman's istic behaviors. In 1 968, Akerman, aged eighteen, -

Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier Olivier Assayas

MK2 presents Juliette Charles Jérémie BINOCHE BERLING RENIER A film by Olivier ASSAYAS photo : Jeannick Gravelines MK2 presents I wanted, as simply as possibly, to tell the story of a life-cycle that resembles that of the seasons… Olivier Assayas a film by Olivier Assayas Starring Juliette Binoche Charles Berling Jérémie Renier France, 35mm, color, 2008. Running time : 102’ in coproduction with France 3 Cinéma and the participation of the Musée d’Orsay and of Canal+ and TPS Star with the support of the Region of Ile-de-France in partnership with the CNC I nt E rnationa L S A LE S MK2 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 55 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 [email protected] PRESS MK2 - 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris tel : + 33 1 44 67 30 11 / fax : + 33 1 43 07 29 63 SYNOPSIS The divergent paths of three forty something siblings collide when their mother, heiress to her uncle’s exceptional 19th century art collection, dies suddenly. Left to come to terms with themselves and their differences, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche) a successful New York designer, Frédéric (Charles Berling) an economist and university professor in Paris, and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier) a dynamic businessman in China, confront the end of childhood, their shared memories, background and unique vision of the future. 1 ABOUT SUMMER HOURS: INTERVIEW WITH OLIVIER ASSAYAS The script of your film was inspired by an initiative from the Musée d’Orsay. Was this a constraint during the writing process? Not at all. In the beginning, there was the desire of the Musée d’Orsay to associate cinema with the celebrations of its twentieth birthday by offering «carte blanche» to four directors from very different backgrounds. -

Colcoa-Press-2019-Part IV

September 19, 2019 COLCOA French Film Festival Monday, September 23 – Saturday, September 28 DGA in Hollywood $$ This film festival showcases the latest work from France. It only looks like it the Coca Cola Film Festival if you read it too fast. September 3, 2019 Critic's Picks: A September To-Do List for Film Buffs in L.A Alain Delon in 'Purple Moon' (1960) A classic lesbian drama, French noirs starring Alain Delon and Jean Gabin and a series of matinees devoted to Katharine Hepburn are among the plentiful vintage and classic options for SoCal film buffs this month. OLIVIA AT THE LAEMMLE ROYAL | 11523 Santa Monica Blvd. Already underway and screening daily through Sept. 5 at the Laemmle Royal is a new digital restoration of Jacqueline Audry’s trailblazing 1951 feature Olivia, one of the first films, French or otherwise, to deal with female homosexuality. Set in a 19th-century Parisian finishing school for girls, the film depicts the struggle between two head mistresses (Edwige Feuillere and Simone Simon) for the affection of their students, and how one girl’s (Marie-Claire Olivia) romantic urges stir jealousy in the house. Audry, one of the key female filmmakers of post-World War II France, stages this feverish chamber drama (based on a novel by the English writer Dorothy Bussy) with a delicate yet incisive touch, allowing the story’s implicit sensuality to simmer ominously without boiling over into undue hysterics. Lesbian dramas would soon become more explicit, but few have matched Olivia’s unique combination of elegance and eroticism. FRENCH FILM NOIR AND KATHARINE HEPBURN MATINEES AT THE AERO | 1328 Montana Ave. -

PRÉSENTATION DE LA 33E ÉDITION

PRÉSENTATION DE LA 33e ÉDITION Collection Gaumont Collection Collections CINEMATEK - @ Chantal Akerman Foundation - @ Chantal Akerman CINEMATEK Collections © Christian Schulz Président du Festival : Jérôme CLÉMENT Président de l’Association : Jean-Michel CLAUDE Délégué Général et Directeur Artistique : Claude-Éric POIROUX www.premiersplans.org LES PARTENAIRES Partenaires institutionnels Mécènes Partenaires privés Organismes professionnels Dossier de présentation Festival Premiers Plans - 33e édition - 25 / 31 janvier 2021 2 Dossier de présentation Festival Premiers Plans - 33e édition - 25 / 31 janvier 2021 3 Lieux partenaires Partenaires de l’éducation et de l’enseignement supérieur Partenaires techniques COMMUNICATION Partenaires médias Le Festival Premiers Plans remercie ACOR - association des cinémas de l’ouest pour la recherche / Angers Nantes Opéra / Anjou Théâtre / Allô Angers Taxi / Ambassade de France et Institut Français d’Algérie / Les Amis du Comedy Club / Angers Loire Métropole / Appart’City / Association de la cause freudienne d’Angers / Association pour le Développementde la Fiction / BiblioPôle / Bibliothèque municipale d’Angers / Boîtes à Culture de Bouchemaine / Le Boléro / Bureau d’Accueil des Tournages des Pays de la Loire / Centre Hospitalier Universitaire / Ciné’fil de Lys-Haut- Layon / Ciné-ma Différence / Cinéma Parlant / Le Chabada / Direction Générale de l’Enseignement scolaire / DSDEN 49 - Direction des services départementaux de l’éducation nationale / Douces Angevines / Écran Total / Esra Bretagne / Fé2A - -

It's Not Just an Image

and geographical surroundings. The most obvious example of this approach may be found in News From Home (1976), in which shots of mostly empty New York streets are accompanied on the soundtrack by the director reading excerpts of letters from her mother back in Bel It’s Not Just gium. Whether in “fiction” films like Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 10800 Bruxelles (1975) or Toute Une Nuit (1982) or diaristic films such as Je tu il elle (1974) or Hotel Monterey (1972), Akerman manages to consistently integrate different, yet complementary, ways of seeing into each film. The installation is divided into three sections. In the first, the spectator enters a an Image room in which the film D ’Est is projected continuously. In the second, twenty-four television monitors, divided into eight triptychs, fragment various sequences from the film. In the last room, a single monitor features a shot moving down a winter street, at night, with Akerman’s voice reading from a biblical text in Hebrew as well as selections from her own notes in En glish and French. The installation is, to use Akerman’s own term, a “translation” of many of the ele A Conversation with ments of the film into another context. In fact, one is struck by the filmmaker’s description of these elements—faces, streets, cars, food, and so on—as a kind of anthology, an attempt to describe a place in which she is a visitor. “I’d like to shoot everything.” But it was not that simple. Before any footage for DEst was shot, Akerman made a Chantal Akerman trip to Russia, where despite the obvious differences of language and culture, she felt “at home.” She attributed this to her personal history: Her parents had emigrated from Poland to Belgium, where she grew up. -

De L'autre Côté

GRAND FORMAT De l’autre côté Réalisé par Chantal Akerman Coproduction : ARTE France, AMIP (2002 – 1h39) En sélection officielle – Festival de Cannes 2002 22.15 Lundi 16 décembre 2002 Contact presse : Céline Chevalier / Nadia Refsi / Rima Matta - 01 55 00 70 41 / 23 / 40 / [email protected] Retrouvez les dossiers de presse en ligne sur www.artepro.com “Parce qu’il y en a qui ont tout et d’autres rien. Voilà De l’autre côté la vie du clandestin.” Documentaire de Chantal Akerman (Un Mexicain) Francisco, Reymundo et les autres sont mexicains. En quête “J’ai peur des d’une vie meilleure, ils veulent passer “de l’autre côté”, aux Mexicains qui arrivent ici en États-Unis. Mais la fuite vers l’eldorado tourne souvent mal. masse. Ils peuvent Un documentaire poignant, dernier volet d’un triptyque de faire pareil [que le Chantal Akerman commencé avec D’Est (1993) et Sud (1999). 11 septembre]. Ils peuvent prendre le “De l’autre côté” : dès 14 ans, ils ont tous ces mots à la bouche. Le pouvoir d o c u m e n t a i re retrace les parcours de migrants mexicains qui se et faire beaucoup heurtent à une frontière américaine extrêmement bien gardée. Fuyant la de dégâts.” pauvreté, ils butent sur les technologies les plus sophistiquées qu’utilise (Une femme rancher) le service d’immigration américain pour les arrêter – des militaires parlent de “guerre quotidienne”. Des panneaux surgissent le long de la frontière : “Halte à la montée du crime !”, “Nos propriétés et notre environnement sont dévastés par l’invasion”… Repoussés en Californie, les candidats à l’émigration tentent leur chance ailleurs, en Arizona, région désertique et montagneuse où le voyage est d’autant plus périlleux.