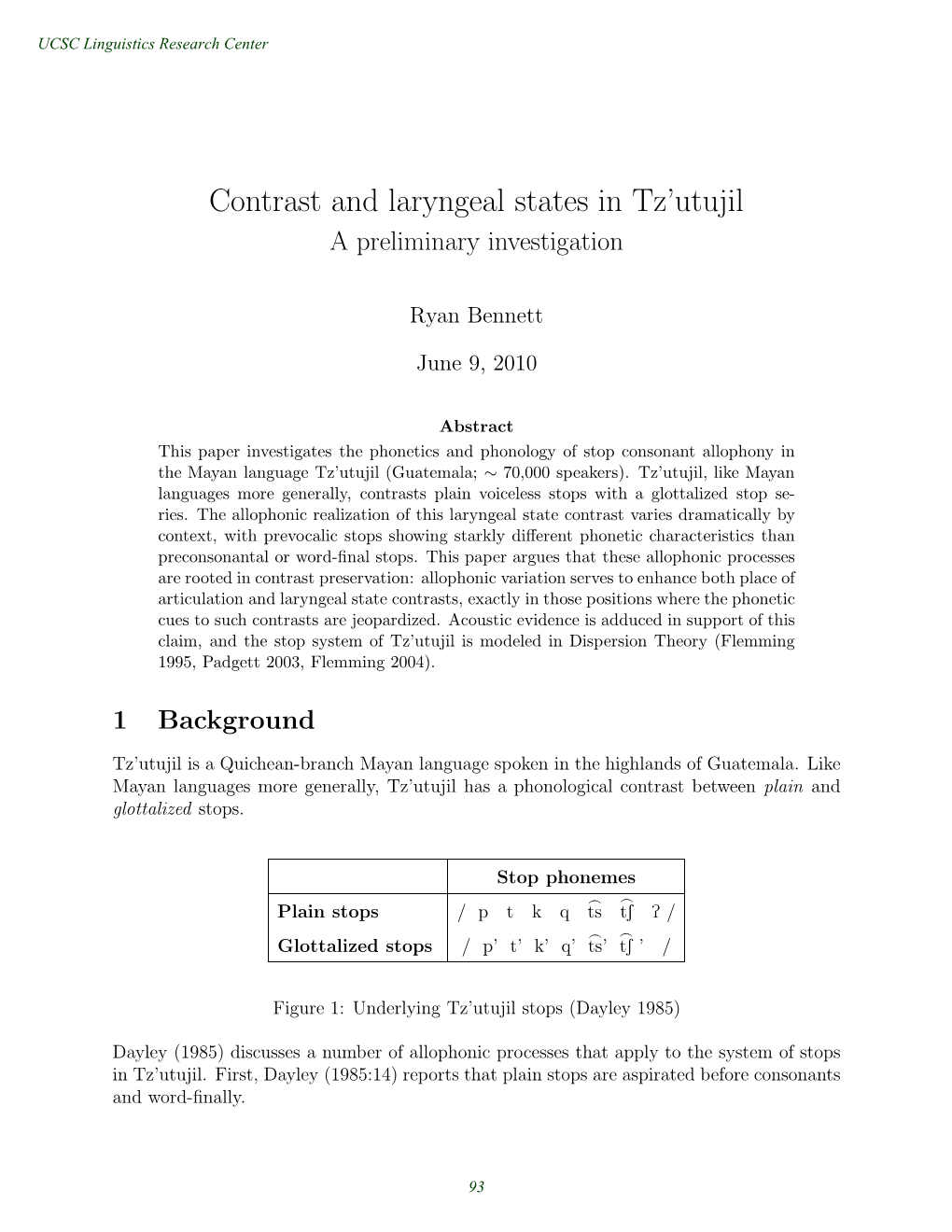

Contrast and Laryngeal States in Tz'utujil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoustic Analysis of English Codas by Mandarin Learners of English

SST 2012 Acoustic Analysis of English Codas by Mandarin Learners of English Nan Xu and Katherine Demuth Child Language Lab, Linguistics Department, ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University [email protected] this coda voicing contrast as Mandarin does not allow for stop Abstract codas, but with increased exposure to native English, their Mandarin has a much more limited segmental inventory than production should match more closely that of native English English, and permits only nasals in coda position, presenting a speakers [6]. Production studies of native English-speaking challenge for learners of English. However, previous studies adults show that there are many potential cues to stop coda have mainly explored this issue using perceptual transcription. voicing, including the duration of the preceding vowel, This study provides an acoustic analysis of coda consonant presence of a voice bar (i.e., low-frequency periodicity productions by Mandarin L2 learners of Australian English. indicating continued vocal fold vibration after oral closure), The results indicate that they produced voiceless stop and closure duration and the presence of aspiration noise produced fricative codas well, but exhibit considerable difficulty with after the oral release [5, 9, 11]. However, the results from [6] voicing contrasts and coda clusters. These findings and their showed that, regardless of length of exposure to English, theoretical implications for current models of L2 learning are Mandarin speakers had non-native acoustic measures for coda discussed. voicing contrasts (closure duration, vowel duration, and changes in F1) and used voice bar to indicate voicing on less Index Terms: Mandarin, English, second language learning, than 20% of the target /d/ codas. -

Some Notes on Implosive Consonants in Nyangatom

Studies in Ethiopian Languages, 5 (2016), 11-20 Some Notes on Implosive Consonants in Nyangatom Moges Yigezu (Addis Ababa University) [email protected] Abstract Nyangatom is a member of the Teso-Turkana cluster within the Eastern-Niltoic group of languages (Vossen 1982) and is spoken in Ethiopia, in the lower Omo valley, by approximately 25,000 speakers (CSA 2008). While there is a detailed description on the Turkana variety spoken in Kenya (Heine 1980, Dimmendaal 1983) there are few grammatical sketches on the Nyangatom variety (Dimmendaal (2007) and Kadanya & Schroder (2011)) spoken in Ethiopia. The status of implosives in the Teso-Turkana group in general and in Nyangatom in particular has not been investigated more clearly and different authors have reached different conclusions in the past. Heine (1980), for instance, recorded implosives as having a phonemic status in Turkana while Dimmendaal (1983) has described implosives in Turkana as variants of their voiced counterparts. In Nyangatom the grammatical sketches published so far have not identified implosive consonants as phonemes of the language. The current contribution gives a preliminary phonological analysis of implosives in Nyangatom with some comparative-historical notes and claim that implosives are full-fledged phonemes in Nyangatom and the opposition is between voiceless stops and implosives while the voiced stops are virtually absent from the phonological system. 1 Introduction Nyangatom belongs to the Teso- Turkana dialect cluster that consists of four major groups and spread over four East African countries, namely, the Nyangatom in Ethiopia, the Toposa in Southern Sudan, the Turkana in Kenya, and the Karamojong in North Eastern Uganda. -

PREAMBLE Co-Dependents Anonymous Is a Fellowship of Men and Women Whose Common Purpose Is to Develop Healthy Relationships

PREAMBLE Co-Dependents Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women whose common purpose is to develop healthy relationships. The only requirement for membership is a desire for healthy and loving relationships. We gather together to support and share with each other in a journey of self-discovery- learning to love the self. Living the program allows each of us to become increasingly honest with ourselves about our personal histories and our own codependent behaviors. We rely upon the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions for knowledge and wisdom. These are the principles of our program and guides to developing honest and fulfilling relationships with ourselves and others. In CoDA we each learn to build a bridge to a Higher Power of our own understanding, and we allow others the same privilege. This renewal process is a gift of healing for us. By actively working the program of Co-Dependents Anonymous, we can each realize a new joy, acceptance, and serenity in our lives. WELCOME (Short Version) We welcome you to Co-Dependents Anonymous - a program of recovery from codependence, where each of us may share our experience, strength, and hope in our efforts to find freedom where there has been bondage, and peace where there has been turmoil in our relationships with others and ourselves. Codependence is a deeply-rooted, compulsive behaviour. It is born out of our sometimes moderately, sometimes extremely dysfunctional family systems. We attempted to use others as our sole source of identity, value, well-being, and as a way of trying to restore our emotional losses. -

"Courts Have Twisted Themselves Into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2016 "Courts Have Twisted Themselves into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art Jane C. Ginsburg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Jane C. Ginsburg, "Courts Have Twisted Themselves into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art, COLUMBIA JOURNAL OF LAW & THE ARTS, VOL. 40, P. 1, 2016; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 14-526 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2000 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [For Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, 100916; rev 200916; 051016] “Courts have twisted themselves into knots”: US Copyright Protection for Applied Art Jane C. Ginsburg, Columbia University School of Law* Abstract: In copyright law, the marriage of beauty and utility often proves fraught. Domestic and international law makers have struggled to determine whether, and to what extent, copyright should cover works that are both artistic and functional. The U.S. Copyright Act protects a work of applied art "only if, and only to the extent that, its design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article." While the policy goal to separate the aesthetic from the functional is clear, courts' application of the statutory "separability" standard has become so complex and incoherent that the U.S. -

Investigation of the Consonant Endings of the Chaoshan Dialect: a Result of Language Contact and Horizontal Transmission

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-8-2020 INVESTIGATION OF THE CONSONANT ENDINGS OF THE CHAOSHAN DIALECT: A RESULT OF LANGUAGE CONTACT AND HORIZONTAL TRANSMISSION Jin Chen University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Comparative and Historical Linguistics Commons, and the Computational Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Jin, "INVESTIGATION OF THE CONSONANT ENDINGS OF THE CHAOSHAN DIALECT: A RESULT OF LANGUAGE CONTACT AND HORIZONTAL TRANSMISSION" (2020). Masters Theses. 903. https://doi.org/10.7275/17376168 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/903 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF THE CONSONANT ENDINGS OF THE CHAOSHAN DIALECT: A RESULT OF LANGUAGE CONTACT AND HORIZONTAL TRANSMISSION A Thesis Presented by JIN CHEN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Chinese © Copyright by Jin Chen 2020 All Rights Reserved INVESTIGATION OF THE CONSONANT ENDINGS OF THE CHAOSHAN DIALECT: A RESULT OF LANGUAGE CONTACT AND HORIZONTAL TRANSMISSION -

WHOM SAY YE THAT I AM? (An Easter Cantata) by LYLE HADLOCK

WHOM SAY YE THAT I AM? (An Easter Cantata) BY LYLE HADLOCK Flute ¡ 4 ú ú . j ú Ï ú Ï. Ï Ï . & 4 Î Ï Ï Ï bÏ Ï J bú ¢ (spoken narration) He lived here on earth 2000 years ago. He was the only person that was without sin and completely without blemish. 4 j & 4 w Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Piano w mp ú. Ï Ï bú. Ï ú úÏ. bú. Ï w w ú ú ? 4 w w w ú ú w = 6 Fl. ¡ Ï Ï ú. ú Ï. Ï & Ï ú Ï Ï Ï ú Ï. J J w ¢ He is known by many names, but most commonly as Jesus Christ. Let's step back in time to clearly understand the role our Savior played, His love, and the sacrifice He made for us. & Ï ú ÏÏ Ï w w ú. Ï Ï Pno ú. Ï Ï ú Ï Ï w ú. Ï Ï w w w ? ú ú ú ú ú ú ú ú w w w 11 = U Ï Fl. ¡ j Ï. Ï & Ï Ï Ï. Ï ú. Î Î J w ¢ Countless Old Testament prophecies proclaimed His birth, His life, and His sacrifice. Matthew tells us "When Jesus (came unto His disciples and) asked, Whom do men say that I the Son of Man am? U Ï Ï ú ÏÏ ú Ï Ï Ï & Ï ú Ï ú Ï ú. Ï Pno ú Ï Ï ú. Ï mf . j Ï Ï ? ú ú ú. Ï ä ú Ï #w ú ú #ú. -

Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus Orca

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Fall 12-2014 Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus orca Courtney Elizabeth Smith University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Animal Studies Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Courtney Elizabeth, "Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus orca" (2014). Master's Theses. 61. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/61 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi DIALECT USE WITHIN A SOCIALLY FLUID GROUP OF SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALES, ORCINUS ORCA by Courtney Elizabeth Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved: Dr. Stan Kuczaj_______________________ Committee Chair Dr. Alen Hajnal_______________________ Dr. Sheree Watson____________________ Dr. Karen Coats______________________ Dean of the Graduate School December 2014 ABSTRACT DIALECT USE WITHIN A SOCIALLY FLUID GROUP OF SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALES, ORCINUS ORCA by Courtney Elizabeth Smith December 2014 Resident killer whales, Orcinus orca, of the Northeastern Pacific form stable kinship-based matrifocal associations and communicate with group-specific repertoires of discrete calls (dialects) that reflect these associations. The gradual fission of matrilines is usually consistent with dialect variations among groups that may manifest as differences in call usage at the repertoire level or subtle structural differences of the calls themselves. -

The Acquisition of Plosives and Implosives by a Fulfulde-Speaking Child Aged from 5 to 10

ICPhS XVII Regular Session Hong Kong, 17-21 August 2011 THE ACQUISITION OF PLOSIVES AND IMPLOSIVES BY A FULFULDE-SPEAKING CHILD AGED1 FROM 5 TO 10;29 MONTHS Ibrahima Cissé, Didier Demolin & Nathalie Vallée Gipsa-lab, CNRS, Grenoble Université, France [email protected] ABSTRACT half an hour twice a month from the age of 5 months to 10 months 29 days in his family (in the This paper reports an analysis of the acquisition of village of Nokara). M was recorded interacting plosives and implosives by a Fulfulde monolingual with his mother during “normal” daily life child aged from 5 months to 10 months and 29 activities. M is growing up in a Fulfulde days. Analyses revealed that before 11 months the monolingual family and village. child was making use of complex consonant-like implosives and prenasal plosives. We provided 2.1.2. The adult data new aerodynamic analyses of adult‟s implosive /ɓ/. These aerodynamic data revealed that in Fulfulde The adult data on implosives are from I., a 28 this phoneme exhibits both voiced and voiceless years old male native speaker of Fulfulde from allophones. Nokara. A list of words containing implosives was recorded. Each word was recorded 3 times using Keywords: acquisition of plosives and implosives, an EVA2® portable workstation. This portable Fulfulde workstation provides simultaneously synchronized intra-oral pressure (Ps) measured in hPa and an 1. INTRODUCTION audio waveform of speech. The audio recording Research on child phonological acquisition focuses sampling was at 44100KHz. on several aspects of the emergence of speech production in children: prosody [7], segments [2], 2.2. -

A Patois of Saintonge: Descriptive Analysis of an Idiolect and Assessment of Present State of Saintongeais

70-13,996 CHIDAINE, John Gabriel, 1922- A PATOIS OF SAINTONGE: DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF AN IDIOLECT AND ASSESSMENT OF PRESENT STATE OF SAINTONGEAIS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Language and Literature, linguistics University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan •3 COPYRIGHT BY JOHN GABRIEL CHIDAINE 1970 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED A PATOIS OF SAINTONGE : DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF AN IDIOLECT AND ASSESSMENT OF PRESENT STATE OF SAINTONGEAIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Chidaine, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Depart w .. w PLEASE NOTE: Not original copy. Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS PREFACE The number of studies which have been undertaken with regard to the southwestern dialects of the langue d'oi'l area is astonishingly small. Most deal with diachronic considerations. As for the dialect of Saintonge only a few articles are available. This whole area, which until a few generations ago contained a variety of apparently closely related patois or dialects— such as Aunisian, Saintongeais, and others in Lower Poitou— , is today for the most part devoid of them. All traces of a local speech have now’ disappeared from Aunis. And in Saintonge, patois speakers are very limited as to their number even in the most remote villages. The present study consists of three distinct and unequal phases: one pertaining to the discovering and gethering of an adequate sample of Saintongeais patois, as it is spoken today* another presenting a synchronic analysis of its most pertinent features; and, finally, one attempting to interpret the results of this analysis in the light of time and area dimensions. -

Notes on Daakie (Port Vato): Sounds and Modality

Proceedings of the Eighteenth Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) Lauren Eby Clemens Gregory Scontras Maria Polinsky (dir.) AFLA XVIII The Eighteenth Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association Harvard University March 4-6, 2011 NOTES ON DAAKIE (PORT VATO): SOUNDS AND MODALITY Manfred Krifka Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Table of Contents Preface i Byron Ahn Tongan Relative Clauses at the Syntax-Prosody 1-15 Interface Edith Aldridge Event Existentials in Tagalog 16-30 Laura Kalin and TP Serialization in Malagasy 31-45 Edward Keenan Manfred Krifka Notes on Daakie (Port Vato): Sounds and Modality 46-65 Eri Kurniawan Does Sundanese have Prolepsis and/or Raising to 66-79 Object Constructions? Bradley Larson A, B, C, or None of the Above: A C-Command 80-93 Puzzle in Tagalog Anja Latrouite Differential Object Marking in Tagalog 94-109 Dong-yi Lin Interrogative Verb Sequencing Constructions in 110-124 Amis Andreea Nicolae and How Does who Compose? 125-139 Gregory Scontras Eric Potsdam A Direct Analysis of Malagasy Phrasal 140-155 Comparatives Chaokai Shi and A Probe-based Account of Voice Agreement in 156-167 T.-H. Jonah Linl Formosan Languages Doris Ching-jung Yen and Sequences of Pronominal Clitics in Mantauran 168-182 Loren Billings Rukai: V-Deletion and Suppletion The Proceedings of AFLA 18 NOTES ON DAAKIE (PORT VATO): SOUNDS AND MODALITY* Manfred Krifka Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin [email protected] The paper reports from ongoing field work on Daakie (South Ambrym, Vanuatu), also known as Port Vato. -

The Ethiopian Language Area,Journal of Ethio Ian Studies, 8/2167-80

DOCUMEUT RESUME FL 002 580 ED 056 566 46 AUTHOR Ferguson, Charles A. TITLE The Ethiopean LanguageArea. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif. SPONS AGENCY Institute of InternationalStudies (DHEW/OE) Washingtn, D.C. PUB DATE Jul 71 CONTRACT OEC-0-71-1018(823) NOTE 22p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Amharic; Consonants;*Descriptive Linguistics; *Distinctive Features;Geographic Distribution; *Grammar; *LanguageClassification; Language Patterns; LanguageTypology7 Morphology(Languages); Phonemes; *Phonology;Pronunciation; Semitic Languages; Sumali;Structural Analysis; Syntax; Tables (Data); Verbs;Vowels IDENTIFIERS *Ethiopia ABSTRACT This paper constitutesthe fifth chapterof the forthcoming volume Languagein Ethiopia.ft In aneffort to better linguistic area, theauthor analyzes define the particular in the area have phonological and grammaticalfeatures that languages in common. A numberof features havebeen identified as characteristic of the area,and this chapterdiscusses eight phonological and eighteengrammatical characteristicswhich constitute significantitems within thelanguages under illustrate the distributionof these features consideration. Tables is included. among theparticular languages. Alist of references cm Cr. D 1-LtLet_121 ar_.ok 43./4 FL THE ETHIOPIAN LANGUAGEAREA Charles A. Ferguson HEW Contract No. OEC-0-71-1018(823) Institute of InternationalStudies U.S. Office of Education U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION & WcI PARE OFFICE In- EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRO M TH E PERSONOR ORGANIZATION -

Editors' Note of Squawking Seagulls and The

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY Editors’ Note With this issue, the review section of Bible & Critical Theory begins a new series of “Books and Culture” review essays. Alongside traditional scholarly book reviews of select new titles in biblical studies, these review essays will feature critical, scholarly engagements, written by established biblical scholars, of books and general culture which are not, per se, directly addressing “biblical scholarship.” At times, the intersection with biblical studies will arise because of an author’s use of Bible—implicit or explicit—in a creative or literary work. Others, however, will feature books that closely intersect with history, literature, economics and cultural studies, critical theory and philosophy, or other fields of scholarship of interest to readers of Bible & Critical Theory. Leading off the series is Peter J. Sabo’s fine engagement with Karl Knausgaard. We welcome your suggestions for books of interest and hope that you find these essays stimulating. Please address your comments and suggestions for future titles to review (or reviewers of interest) to the Book Review Editor, Robert Paul Seesengood, at the address provided by the journal. We hope you enjoy this series. * Of Squawking Seagulls and the Mutable Divine: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s A Time for Everything (With Reference to My Struggle) Books & Culture Review Essay P.J. Sabo An albino, reclusive Noah; a raving, delusional Abel; an asthmatic, kind-hearted, but misunderstood Cain; a solipsistic, hermitic Ezekiel—these versions of biblical characters (among others) can be found in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s A Time for Everything. This novel is idiosyncratic and defies rigid definitions.