Maturation at a Young Age and Small Size of European Smelt (Osmerus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

Effective Population Size and Genetic Conservation Criteria for Bull Trout

North American Journal of Fisheries Management 21:756±764, 2001 q Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 2001 Effective Population Size and Genetic Conservation Criteria for Bull Trout B. E. RIEMAN* U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 316 East Myrtle, Boise, Idaho 83702, USA F. W. A LLENDORF Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA Abstract.ÐEffective population size (Ne) is an important concept in the management of threatened species like bull trout Salvelinus con¯uentus. General guidelines suggest that effective population sizes of 50 or 500 are essential to minimize inbreeding effects or maintain adaptive genetic variation, respectively. Although Ne strongly depends on census population size, it also depends on demographic and life history characteristics that complicate any estimates. This is an especially dif®cult problem for species like bull trout, which have overlapping generations; biologists may monitor annual population number but lack more detailed information on demographic population structure or life history. We used a generalized, age-structured simulation model to relate Ne to adult numbers under a range of life histories and other conditions characteristic of bull trout populations. Effective population size varied strongly with the effects of the demographic and environmental variation included in our simulations. Our most realistic estimates of Ne were between about 0.5 and 1.0 times the mean number of adults spawning annually. We conclude that cautious long-term management goals for bull trout populations should include an average of at least 1,000 adults spawning each year. Where local populations are too small, managers should seek to conserve a collection of interconnected populations that is at least large enough in total to meet this minimum. -

Changing Communities of Baltic Coastal Fish Executive Summary: Assessment of Coastal fi Sh in the Baltic Sea

Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 103 B Changing Communities of Baltic Coastal Fish Executive summary: Assessment of coastal fi sh in the Baltic Sea Helsinki Commission Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 103 B Changing Communities of Baltic Coastal Fish Executive summary: Assessment of coastal fi sh in the Baltic Sea Helsinki Commission Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission Editor: Janet Pawlak Authors: Kaj Ådjers (Co-ordination Organ for Baltic Reference Areas) Jan Andersson (Swedish Board of Fisheries) Magnus Appelberg (Swedish Board of Fisheries) Redik Eschbaum (Estonian Marine Institute) Ronald Fricke (State Museum of Natural History, Stuttgart, Germany) Antti Lappalainen (Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute), Atis Minde (Latvian Fish Resources Agency) Henn Ojaveer (Estonian Marine Institute) Wojciech Pelczarski (Sea Fisheries Institute, Poland) Rimantas Repečka (Institute of Ecology, Lithuania). Photographers: Visa Hietalahti p. cover, 7 top, 8 bottom Johnny Jensen p. 3 top, 3 bottom, 4 middle, 4 bottom, 5 top, 8 top, 9 top, 9 bottom Lauri Urho p. 4 top, 5 bottom Juhani Vaittinen p. 7 bottom Markku Varjo / LKA p. 10 top For bibliographic purposes this document should be cited as: HELCOM, 2006 Changing Communities of Baltic Coastal Fish Executive summary: Assessment of coastal fi sh in the Baltic Sea Balt. Sea Environ. Proc. No. 103 B Information included in this publication or extracts thereof is free for citing on the condition that the complete reference of the publication is given as stated above Copyright 2006 by the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission - Helsinki Commission - Design and layout: Bitdesign, Vantaa, Finland Printed by: Erweko Painotuote Oy, Finland ISSN 0357-2994 Coastal fi sh – a combination of freshwater and marine species Coastal fish communities are important components of Baltic Sea ecosystems. -

Status and Trends of Land Degradation and Restoration and Associated Changes in Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functions

IPBES/6/INF/1/Rev.1 Chapter 4 Status and trends of land degradation and restoration and associated changes in biodiversity and ecosystem functions Coordinating Lead Authors Stephen Prince (United States of America), Graham Von Maltitz (South Africa), Fengchun Zhang (China) Lead Authors Kenneth Byrne (Ireland), Charles Driscoll (United States of America), Gil Eshel (Israel), German Kust (Russian Federation), Cristina Martínez-Garza (Mexico), Jean Paul Metzger (Brazil), Guy Midgley (South Africa), David Moreno Mateos (Spain), Mongi Sghaier (Tunisia/OSS), San Thwin (Myanmar) Fellow Bernard Nuoleyeng Baatuuwie (Ghana) Contributing Authors Albert Bleeker (the Netherlands), Molly E. Brown (United States of America), Leilei Cheng (China), Kirsten Dales (Canada), Evan Andrew Ellicot (United States of America), Geraldo Wilson Fernandes (Brazil), Violette Geissen (the Netherlands), Panu Halme (Finland), Jim Harris (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland), Roberto Cesar Izaurralde (United States of America), Robert Jandl (Austria), Gensuo Jia (China), Guo Li (China), Richard Lindsay (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland), Giuseppe Molinario (United States of America), Mohamed Neffati (Tunisia), Margaret Palmer (United States of America), John Parrotta (United States of America), Gary Pierzynski (United States of America), Tobias Plieninger (Germany), Pascal Podwojewski (France), Bernardo Dourado Ranieri (Brazil), Mahesh Sankaran (India), Robert Scholes (South Africa), Kate Tully (United States of America), Ernesto F. Viglizzo (Argentina), Fei Wang (China), Nengwen Xiao (China), Qing Ying (China), Caiyun Zhao (China) Review Editors Chencho Norbu (Bhutan), Jim Reynolds (United States of America) This chapter should be cited as: Prince, S., Von Maltitz, G., Zhang, F., Byrne, K., Driscoll, C., Eshel, G., Kust, G., Martínez-Garza, C., Metzger, J. -

Ecocide: the Missing Crime Against Peace'

35 690 Initiative paper from Representative Van Raan: 'Ecocide: The missing crime against peace' No. 2 INITIATIVE PAPER 'The rules of our world are laws, and they can be changed. Laws can restrict, or they can enable. What matters is what they serve. Many of the laws in our world serve property - they are based on ownership. But imagine a law that has a higher moral authority… a law that puts people and planet first. Imagine a law that starts from first do no harm, that stops this dangerous game and takes us to a place of safety….' Polly Higgins, 2015 'We need to change the rules.' Greta Thunberg, 2019 Table of contents Summary 1 1. Introduction 3 2. The ineffectiveness of current legislation 7 3. The legal framework for ecocide law 14 4. Case study: West Papua 20 5. Conclusion 25 6. Financial section 26 7. Decision points 26 Appendix: The institutional history of ecocide 29 Summary Despite all our efforts, the future of our natural environments, habitats, and ecosystems does not look promising. Human activity has ensured that climate change continues to persist. Legal instruments are available to combat this unprecedented damage to the natural living environment, but these instruments have proven inadequate. With this paper, the initiator intends to set forth an innovative new legal concept. This paper is a study into the possibilities of turning this unprecedented destruction of our natural environment into a criminal offence. In this regard, we will use the term ecocide, defined as the extensive damage to or destruction of ecosystems through human activity. -

Desertification and Agriculture

BRIEFING Desertification and agriculture SUMMARY Desertification is a land degradation process that occurs in drylands. It affects the land's capacity to supply ecosystem services, such as producing food or hosting biodiversity, to mention the most well-known ones. Its drivers are related to both human activity and the climate, and depend on the specific context. More than 1 billion people in some 100 countries face some level of risk related to the effects of desertification. Climate change can further increase the risk of desertification for those regions of the world that may change into drylands for climatic reasons. Desertification is reversible, but that requires proper indicators to send out alerts about the potential risk of desertification while there is still time and scope for remedial action. However, issues related to the availability and comparability of data across various regions of the world pose big challenges when it comes to measuring and monitoring desertification processes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and the UN sustainable development goals provide a global framework for assessing desertification. The 2018 World Atlas of Desertification introduced the concept of 'convergence of evidence' to identify areas where multiple pressures cause land change processes relevant to land degradation, of which desertification is a striking example. Desertification involves many environmental and socio-economic aspects. It has many causes and triggers many consequences. A major cause is unsustainable agriculture, a major consequence is the threat to food production. To fully comprehend this two-way relationship requires to understand how agriculture affects land quality, what risks land degradation poses for agricultural production and to what extent a change in agricultural practices can reverse the trend. -

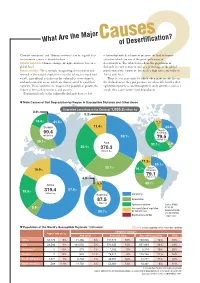

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kuhn, Thomas; Pestow, Radomir; Zenker, Anja Working Paper An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint Chemnitz Economic Papers, No. 025 Provided in Cooperation with: Chemnitz University of Technology, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration Suggested Citation: Kuhn, Thomas; Pestow, Radomir; Zenker, Anja (2018) : An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint, Chemnitz Economic Papers, No. 025, Chemnitz University of Technology, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Chemnitz This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190431 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Faculty of Economics and Business Administration An Axiomatic Foundation of the Ecological Footprint Thomas Kuhn Radomir Pestow Anja Zenker Chemnitz Economic Papers, No. -

In Pomerania Bay, Gdansk Bay and Curonian Lagoon

Journal of Elementology ISSN 1644-2296 Pilarczyk B., Pilecka-Rapacz M., Tomza-Marciniak A., Domagała J., Bąkowska M., Pilarczyk R. 2015. Selenium content in European smelt (Osmerus eperlanus eperlanus L.) in Pomerania Bay, Gdansk Bay and Curonian Lagoon. J. Elem., 20(4): 957-964. DOI: 10.5601/jelem.2015.20.1.876 SELENIUM CONTENT IN EUROPEAN SMELT (OSMERUS EPERLANUS EPERLANUS L.) IN POMERANIA BAY, GDANSK BAY AND CURONIAN LAGOON Bogumiła Pilarczyk1, Małgorzata Pilecka-Rapacz2, Agnieszka Tomza-Marciniak1, Józef Domagała2, Małgorzata Bąkowska1, Renata Pilarczyk3 1Chair of Animal Reproduction Biotechnology and Environmental Hygiene West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin 2 Chair of General Zoology University of Szczecin 3Laboratory of Biostatistics West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin Abstract Migratory smelt (Osmerus eperlanus eperlanus L.) may be perceived as a valuable indicative organism in monitoring the current environmental status and in assessment of a potential risk caused by selenium pollution. The aim of the study was to compare the selenium content in the European smelt from the Bay of Pomerania, Gdansk, and the Curonian Lagoon. The experimen- tal material consisted of smelt samples (muscle) caught in the bays of Gdansk and Pomerania and the Curonian Lagoon (estuaries of the three largest rivers in the Baltic Sea basin: the Oder, the Vistula and the Neman). A total of 133 smelt were examined (Pomerania Bay n = 67; Gdansk Bay n = 35; Curonian Lagoon n = 31). Selenium concentrations were determined spec- trofluorometrically. The data were analyzed statistically using one-way analysis of variance, calculated in Statistica PL software. The region of fish collection significantly affected the content of selenium in the examined smelts. -

Anguillicola Crassus(Nematoda, Dracunculoidea)

Anguillicola crassus (Nematoda, Dracunculoidea) infections of European eel (Anguilla anguilla) in the Netherlands: epidemiology, pathogenesis and pathobiology 23 FEB. 1995 UB-CARDEX Olga Haenen LANDBOUWCATALOGUS 0000 0611 3746 ;cn Promotor : Dr. W.B. van Muiswinkel, Hoogleraar in de Zoölogische Celbiologie Landbouwuniversiteit, Wageningen Co-promotor : Dr. F.H.M. Borgsteede, hoofd sectie Parasitologie DLO-Instituut voor Veehouderij en Diergezondheid, Lelystad VO\ l°10S poll d Anguillicola crassus (Nematoda, Dracunculoidea) infections of European eel (Anguilla anguilla) in the Netherlands: epidemiology,pathogenesi s andpathobiolog y Olga Liduina Maria Haenen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor in de Landbouw- en Milieuwetenschappen, op gezag van de rector magnificus. Dr. CM. Karssen in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 10 maart 1995 des namiddags te vier uur in de aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen isn^Oèf}'! Omslag: Olga Haenen Fotografie: Fred van Welie Joop ledema Vormgeving: Herma Daus-Ooms CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Haenen, Olga Liduina Maria Anguillicola crassus(Nematoda , Dracunculoidea) infections of European eel{Anguilla anguilla) inth eNetherland s : epidemiology, pathogenesis and pathobiology / Olga Liduina Maria Haenen ; [ill.va n deauteur] .- [S.l. : s.n.J- III. Thesis Landbouw Universiteit Wageningen. - With réf. With summary inDutch . ISBN 90-5485-354-9 Subject headings: Anguillicola crassus/ parasitic nematode / eel. LANDEO l' V vU V; VESSITEIT WAü;";Nh\'C£N The study described in this thesis was performed at the DLO-lnstitute for Animal Science and Health, Lelystad, The Netherlands. aan mijn ouders Stellingen 1. De snelle vestiging en verspreiding van Anguillicola crassus in Nederland is mede te danken aan het brede scala van tussengastheren en paratenische gastheren (dit proefschrift). -

This Is the Published Version of a Paper

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Slovak Ethnology. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Svanberg, I., Bonow, M., Cios, S. (2016) Fishing For Smelt, Osmerus Eperlanus (Linnaeus, 1758): A traditional food fish – possible cuisinein post-modern Sweden?. Slovak Ethnology, 2(64) Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. CC BY-NC-ND Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-30594 2 64 • 2016 ARTICLES FISHING FOR SMELT, OSMERUS EPERLANUS (Linnaeus, 1758) A traditional food fish – possible cuisine in post-modern Sweden? INGVAR SVANBERG, MADELEINE BONOW, STANISŁAW CIOS Ingvar Svanberg, Uppsala Centre for Russian Studies, Uppsala University, e-mail: ingvar.svanberg @ucrs.uu.se, Madeleine Bonow, School of natural science, technology and environmental studies, Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden, e-mail: [email protected], Stanisław Cios, Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Warsaw, e-mail: [email protected]. 1 For the rural population in Sweden, fishing in lakes and rivers was of great importance until recently. Many fish species served as food or animal fodder, or were used to make glue and other useful products. But the receding of lakes in the nineteenth century, and the expansion of hydropower and worsening of water pollution in the twentieth, contributed to the decline of inland fisheries. At the same time, marine fish became more competitive on the Swedish food market. In some regions, however, certain freshwater species continued to be caught for household consumption well into the twentieth century. -

Smelt (Osmerus Eperlanus L.) in the Baltic Sea

Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. Biol. Ecol., 2005, 54, 3, 230–241 Smelt (Osmerus eperlanus L.) in the Baltic Sea Heli Shpileva*, Evald Ojaveerb, and Ain Lankova a Pärnu Field Base, Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Vana Sauga 28, 80031 Pärnu, Estonia b Estonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Mäealuse 10a, 12618 Tallinn, Estonia; [email protected] Received 6 September 2004, in revised form 1 December 2004 Abstract. Smelt, a cold-water anadromous fish, has well adapted to the conditions in the brackish Baltic Sea and has formed local populations. The species is common in coastal waters but the most important marine smelt stocks are confined to the areas where the water of low temperature and relatively high oxygen content persists year round, in the neighbourhood of large estuaries and lagoons. The abundance of smelt is higher in the northern and eastern Baltic: in the Gulf of Bothnia, eastern Gulf of Finland, Gulf of Riga, and Curonian Lagoon. Smelt populations of these areas differ in growth rate, maturation, reproduction conditions, abundance and catch dynamics, etc. Smelt reproduction depends on temperature, it starts and finishes earlier in the southern areas than in the north. The growth rate of the fish is higher in the south and decreases towards north. In the Gulf of Riga the size of younger smelt has increased since the end of the 1960s. However, beginning with the early 1990s the weight of older fish has declined. Key words: smelt stocks, abundance dynamics, growth, reproduction. INTRODUCTION European smelt Osmerus eprlanus L. populates brackish waters in the Baltic Sea.